Protest and Activism

Deep Roots

In an ever-changing world, generations of students at Loyola have heard a call to action and responded using the strategies of protest and collective action. From roots in the traditions of debate and social activism, Loyolans have taken up a variety of causes throughout the years, some very small and focused, and some on a far greater scale.

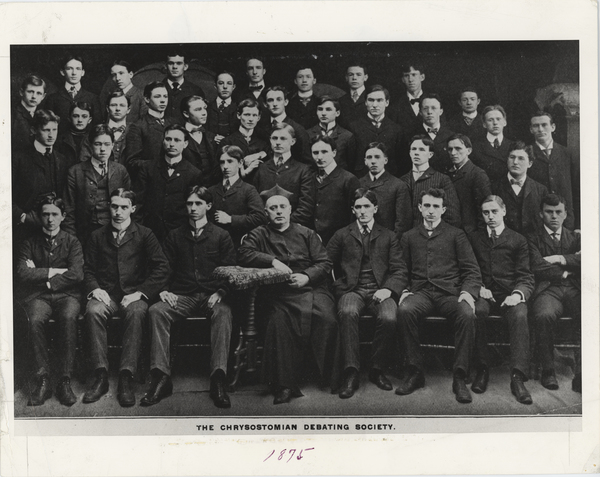

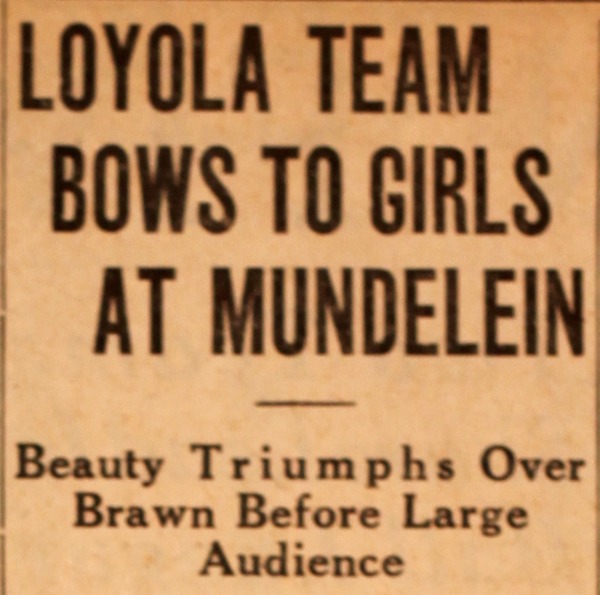

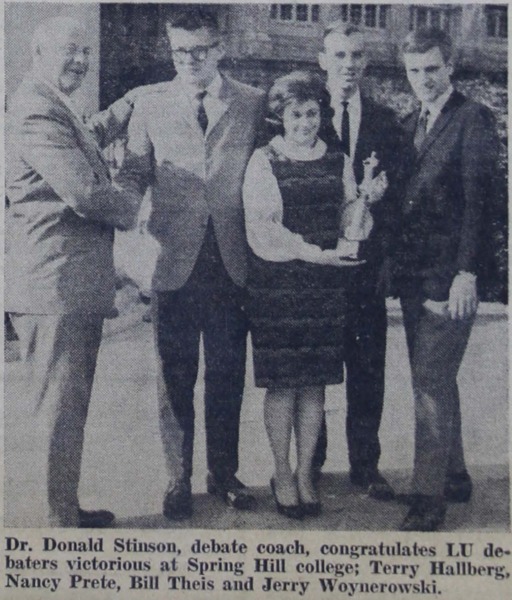

One of the earliest clubs at Loyola was the Chrysostomian Debating Society, where students trained to research contentious topics and defend positions. Debate clubs remained popular through the years, and Mundelein College*, the neighboring women’s college, joined the tradition shortly after their founding in 1930, going toe-to-toe against Loyola debaters and others around the country and earning their respect.

Meanwhile, efforts to improve the lot of their fellow humans led to fundraising efforts, which continue today. Whether to secure food, medical care, or education, students have taken action to help others, aligning with Loyola’s Jesuit mission of care for the whole person, cura personalis. Both schools also developed strong traditions of journalism, each with their own newspaper, which would eventually become a vital forum for student debate and opinion.

Asking New Questions

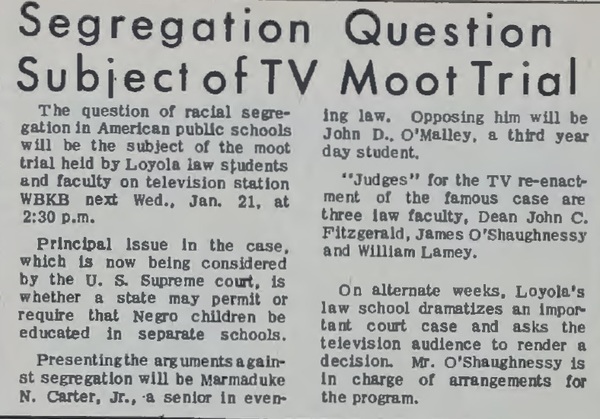

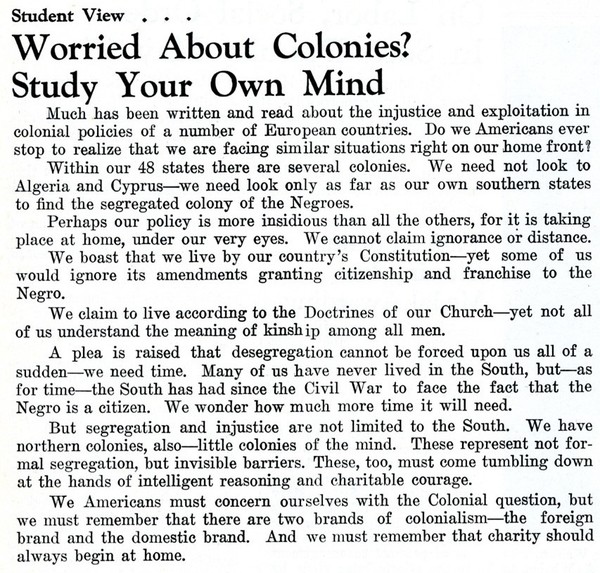

After World War II, as veterans and other students returned to school, many brought new visions of the world informed by a greater interest in the events unfolding around them on a global scale. Student newspapers began to address social issues with less obvious answers, such as segregation, colonialism, and the rise of Communism worldwide. Soon, the tone shifted, and rather than debate these issues in the abstract, students asked what they could do or ought to do about them, as students living in Chicago, and mostly as Catholics.

National Headlines

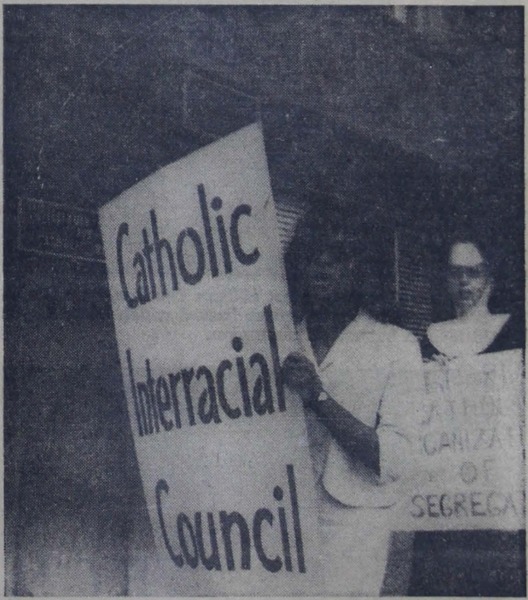

By the 1960s, the answer for many students was to engage in protest and activism, inspired by the techniques of the Civil Rights Movement. In 1963, Micki Leaner, a Black sophomore at Loyola hoping to learn to swim, attempted to use the pool on an upper floor of Lewis Towers, which was owned by the Illinois Club for Catholic Women (ICCW). Leaner was denied entry. With the help of fellow students, she uncovered the ICCW's discriminatory practices and began to picket.

Their demonstrations began to fade after several weeks until they gained the support of a group of seven Franciscan women religious and a priest who had become active in civil rights work. These clergy members joined the picket line on July 1, 1963, which was reportedly the first time women religious in habit had openly joined a protest. The event made national headlines and was featured in The Chicago Defender newspaper and Time magazine. With the clergy's support, the protest gained momentum, and the ICCW capitulated on July 9. However, the pool was then closed for repairs and never re-opened, leaving questions about the finality of the desegregation victory.

Students joining larger protests in downtown Chicago witnessed police brutality, while also observing the peaceful example of the adults and clergy who attended with them. In 1965, a group of Mundelein faculty, students, and guests traveled to join Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in the march from Selma to Montgomery, experiencing Southern discrimination firsthand and returning with much to think about. Loyola hosted a multi-school rally in support of the march as well, with speeches from those who had attended as well as local clergy active in the Civil Rights Movement. Mundelein’s student activities committee also raised funds for the national Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) to help bail out the Freedom Riders, white and African American students from across the country who were frequently jailed in the South while attempting to desegregate bus terminals.

Speaking Out

However, faraway or outside problems were somewhat easier to discuss than those within students' own schools. In the late 1960s, in the aftermath of the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., students of color found the footing to speak of their experiences more openly and point out the barriers they faced, which their white classmates had failed to notice. By forming new student groups, including Loyola’s Afro-American Student Association (LUASA), the Black Cultural Center (BCC), and the Mundelein College United Black Association (MuCUBA), these students were able to use collective action to bring demands to their schools, urging them to dismantle the institutional racism within their walls.

Among the greatest concerns for these students was the conspicuous absence of Black history in the curriculum, as well as a lack of resources for Black students seeking to thrive and build community on campus. Changes promised were not always fully realized, and these issues continue to motivate students to organize into the twenty-first century.

Mobilizing for Peace

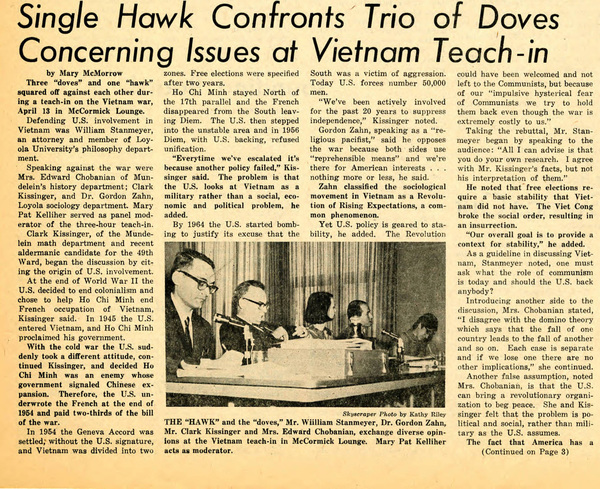

During the Vietnam War, discussions and lectures on the war became a fixture of campus life. Like their peers across the country, Loyola and Mundelein students participated in panels, protests, and vigils as the war grew increasingly unpopular. Both schools participated in the Mobilization, a 10-day disruption of “life as usual” for discussions and lectures on the war. Oral histories and newspaper op-eds told of bitter division and dorm arguments. Faculty from both schools joined for "teach-in” events and debates.

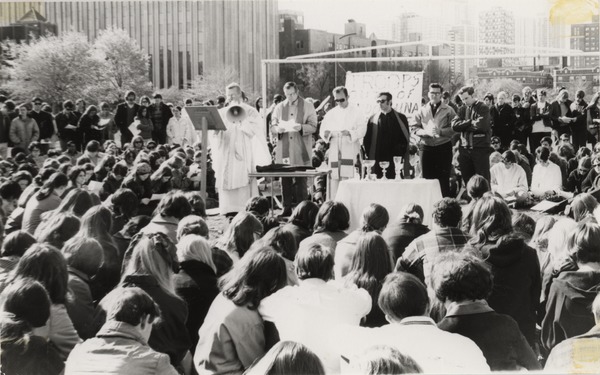

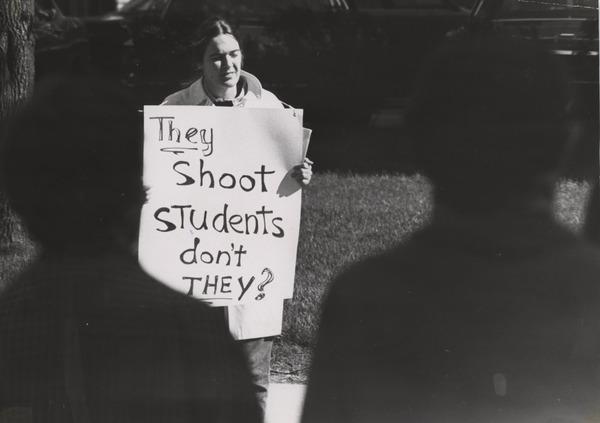

In April of 1970, American forces invaded Cambodia, resulting in public outcry against the escalation of the war. On May 4, 1970, during a student anti-war protest at Kent State University, the Ohio National Guard shot and killed four students. By 4 p.m. the next day, several hundred Loyola students met in Mertz Hall to vote overwhelmingly in favor of a student strike in solidarity. News spread quickly, and by 8 a.m. on May 6, picket lines had formed, a microphone was set up on the Lake Shore Campus athletic field, and mass was held to open the most dramatic strike in Loyola's history.

Over 100 faculty voted to strike as well, and most classes were canceled, except for a few outliers taught by very conservative faculty. Students lowered a flag, turned it upside down, and raised it to half-mast to signal that "America is in distress." Meanwhile, strategy meetings emphasized that the strike would be non-violent, Mundelein College opened a free cafeteria and fed hundreds of participants, and at 8:15 p.m. over 3,000 Loyola and Mundelein students and faculty marched down Broadway Avenue to the armory of the Illinois National Guard. The "mile-long" protest line was met with police presence, yet no violence occurred, and the rally concluded at the beach that evening. A very small portion of Loyolans did not participate or were hostile to the strikers.

Loyola's president, Father Maguire, signed a letter with 33 other university presidents urging President Nixon to take students' concerns seriously and end the war quickly, and stated that "The Loyola community reminds Mr. Nixon of the fact that when government policy turns to violence, it invites tragedy. [...] We, as citizens of the United States and members of the Loyola community, implore our national leaders to end this long and costly madness in Southeast Asia. Our strike is a public expression that our most sensitive moral and intellectual principles [are] grievously offended by the malaise of a war that drags on and a peace that remains elusive." Though some alumni were puzzled or distressed by news of the strike, both schools' leadership did their best to explain the campus situation and emphasized the non-violent nature of the protests.

Fighting Apathy

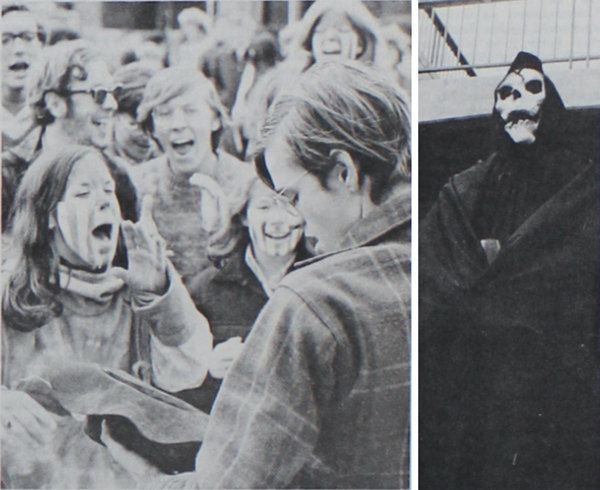

Inspired by their participation in this national anti-war movement, students continued to protest as the war continued. In October 1970, Loyola students staged a "Death Day" demonstration using guerilla theatre tactics to showcase the absurdity of the war in the hopes of shocking passersby out of their apathy. Students marched up to Mertz Hall, chanting, "What do we have the bombs for?" "To Kill... To Kill." "What do we have napalm for?" "To Kill... To Kill." Several scenes followed, including two opposing columns that fought without reason to the 'death,' and a lottery caller inviting students to "Step right up and join in the winningest lottery in the whole world," whereupon they would fall 'dead' as they were called and the cheers gradually faded. The group marched away chanting "Work... Study... Get Ahead... Kill..."

In addition to protesting the war itself, many students resisted the draft and anxiously listened as birthdays were called on national television, dreading that they would hear their own birthday, a friend's, or a loved one's. On April 27, 1971, four Loyola students dubbed "The Four of Us" invaded the Evanston office of the Selective Service system and destroyed hundreds of A-1 draft cards using symbolic blood and waited for police to arrive to arrest them. Days of demonstrations and arrests followed, drawing many university and high school students who opposed the war and the draft.

In 1971, the 26th amendment lowered the voting age from 21 to 18. In 1972, Loyola students hosted the newly formed National Youth Caucus's Conference for New Voters. As a coalition of groups advocating for voter education, the National Youth Caucus brought together over 2,600 delegates from across the country and intended to amplify youth voices in the 1972 election. The tone was described as "anti-Nixon, pro-peace, pro-economic stability, and pro-racial equality." At times, representatives from minority groups "struggled to be heard." Though their platform did not change the election's result, thousands of young people were registered to vote at Loyola that year, and civic involvement at Loyola continued to grow.

Clashes Close to Home

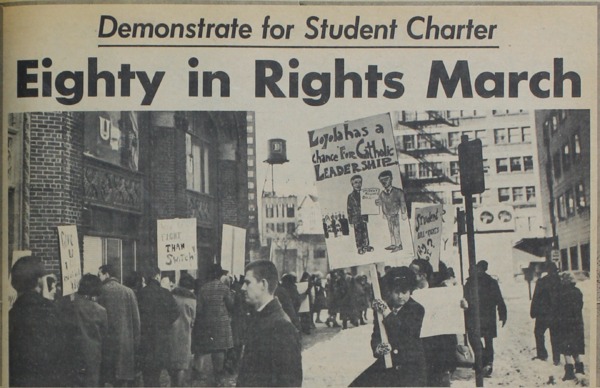

From the 1960s on, new and old student organizations used protests and collective action to address issues on campus. As at many schools nationwide, students clashed with the school administration over various issues such as dining and living costs and freedom of speech.

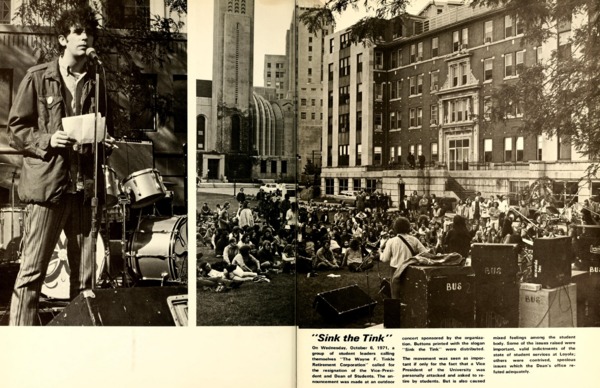

One notable movement, “The Wayne F. Tinkle Retirement Corporation,” with the motto “Sink the Tink,” demanded the resignation of Loyola administrator Wayne F. Tinkle in 1971 based on five complaints, including the firing of two popular administrators, the lack of intervention in widespread heroin problems on campus, the lack of doctors available for students, and the administration’s refusal to allow sales of Playboy magazine on campus. "The Wayne F. Tinkle Retirement Corporation" achieved some of its demands. Similarly, many student protests have been taken seriously, while some were seen as unrealistic. Some were more successful than others at spurring change.

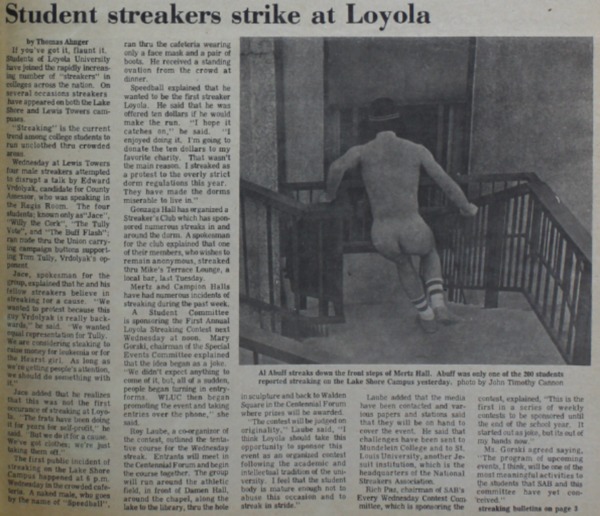

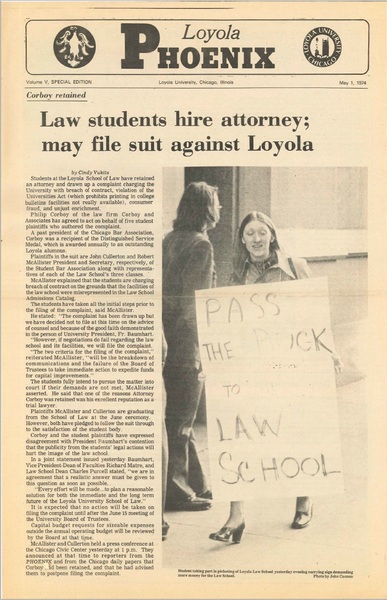

In 1974, law students alerted Loyola that their library was too cramped for the needs of the growing law school. When the school failed to take action, the students packed the law library with a 350-person "study-in" and, with the help of an alumnus, threatened to sue. Soon, work on the updated library began. In a more lighthearted episode the same year, a slew of streakers “struck” Loyola—while some streaked for the fun of it, others claimed to “streak for a cause” in support of a political candidate or to raise money for charity.

Reaching Out

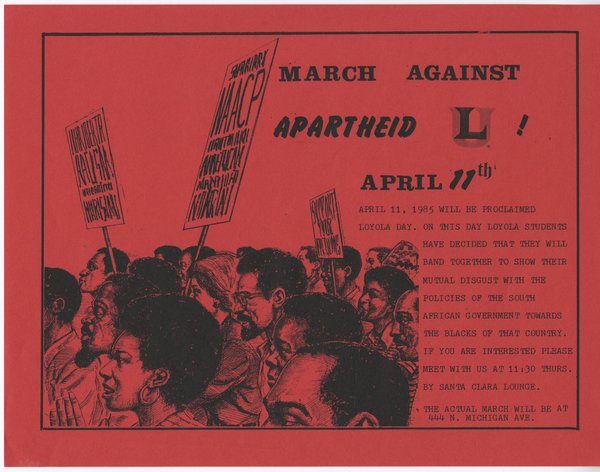

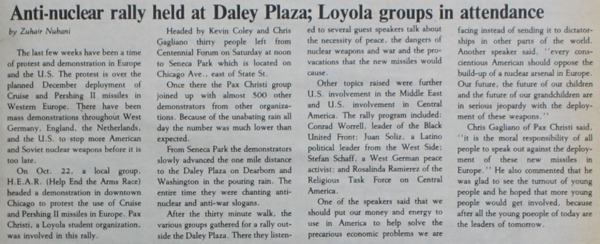

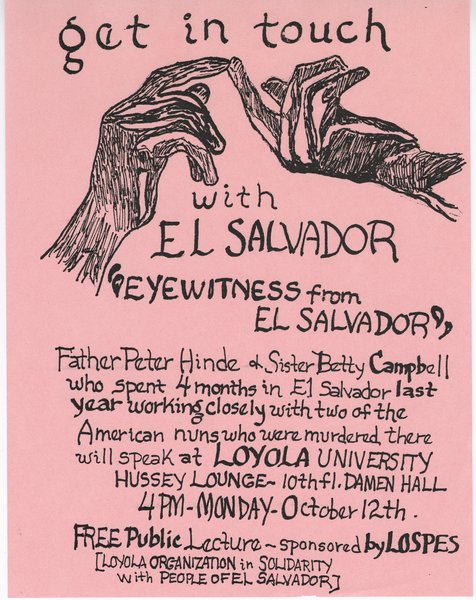

The 1980s brought new concern for global issues, including hunger, poverty, the nuclear arms race, and increasing American military involvement around the world. A variety of campus groups, such as Pax Christi; Peace, Bread & Justice; and LOSPES (Loyola Organization in Solidarity with the People of El Salvador) formed coalitions with like-minded groups at other schools and took their goals beyond campus by joining in both local and national demonstrations to call on elected officials to act. They also continued to host talks and raise funds to help provide relief around the world.

In the following decades, Loyola and Mundelein students continued using techniques such as protests and sit-ins to make their voices heard. The 1990s saw national demonstrations against the Iraq War and the continued United States involvement in El Salvador. Into the 2000s and 2010s, students have joined in national marches to demand action on climate change, to express solidarity with sweatshop and agricultural workers, and to stand up for women's rights.

Standing Together

Protests on campus organized by students and faculty have also responded to injustice and called for change. In 2018, the #NotMyLoyola movement formed after an incident of use of excessive force on a racial basis by police on campus. Students staged a walk-out and urged Loyola to reexamine its relationship with the Chicago Police Department.

In May 2020, during the COVID-19 pandemic, outrage over the murder of George Floyd, an unarmed Black man, by police in Minneapolis sparked nationwide protests. Loyola students formed the Our Streets LUC movement to protest for racial justice on campus with the international Black Lives Matter movement. Protests continued throughout the summer and into the fall of 2020. Many of these protests have spurred action from the University, including the formation of Loyola's Institute for Racial Justice and the Anti-Racism Initiative.

By advocating for their own needs and the needs of others, Loyolans continue a decades-old tradition and will no doubt continue to use these techniques to speak out, join arms in civic engagement, and advocate for positive change in their school, their communities, and the world around them.