World War II

Distant Rumblings

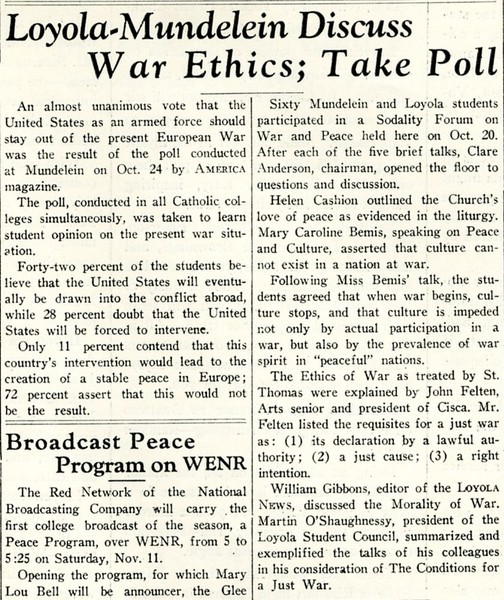

In the 1930s, as tensions rose in Europe, students at Loyola and Mundelein* could not ignore questions about the possibility of war and the role the United States should play in it. Before 1939, the majority of Loyola students initially opposed any war, a common sentiment among Americans, including American Catholics. Most students would have been too young to remember the Great War -- World War I -- which ended in 1919, but it was recent in the nation’s memory. Peace was their priority, as a national student poll showed an overwhelming majority were opposed to American assistance in any war.

In 1939, Germany invaded Poland, marking the official beginning of World War II. The United States, still in recession, initially sat out of the war, and life at both schools continued much as it had been. Students read news reports and formed strong opinions about U.S. involvement and the lend-lease program to send supplies to England. Many still felt that the U.S. should stay out of the war entirely. Meanwhile, a significant portion of students felt that the U.S. should stay out of Europe, but for a different reason. Fearing a direct attack on U.S. soil, these students felt that the U.S. ought to focus on its own defenses and avoid stretching its resources too thin.

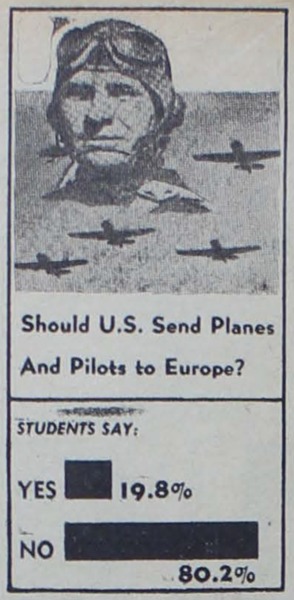

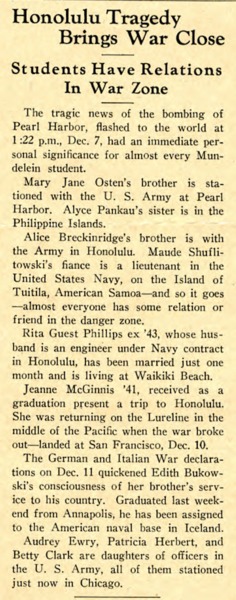

On December 7, 1941, the Japanese bombing of the U.S. base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, shocked the country. The first Loyolan to be killed in the war, an alumnus of the medical school, was killed in the bombing. Many Loyola and Mundelein students had friends or loved ones at Pearl Harbor, and the war suddenly felt much closer to home.

The Home Front Comes to Campus

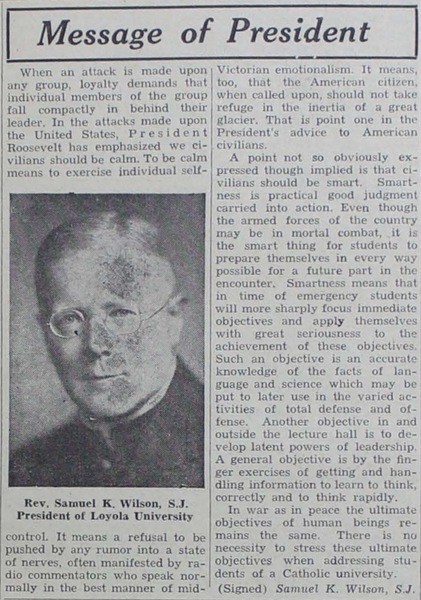

Following Pearl Harbor, the United States entered the war, and the tone at Loyola and Mundelein shifted to support the war effort. Loyola President Rev. Wilson, S.J. urged students to remain calm and think carefully about how they could prepare for the fight ahead. More students, faculty, and graduates began enlisting in the armed forces.

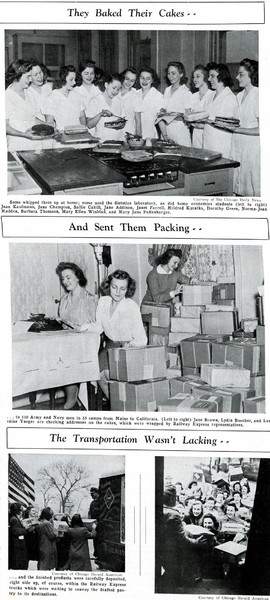

Loyola students who remained on campus organized to support the victory effort. In 1944, students raised $1,950 to buy an ambulance for use in Europe and continued to sell war bonds and stamps throughout the war. Similarly, Mundelein students organized fundraisers, a Jeep drive, and scrap metal drives, and saved their sugar rations to bake hundreds of cakes to raise the spirits of soldiers on training bases across the country. Students at both schools raised funds to relieve starvation and suffering among civilians in war-torn Europe during and after the war.

Meanwhile, to keep spirits up, student organizations continued throwing parties and holding club meetings, albeit with reduced resources and smaller turnouts. Loyolans did their best to put together a basketball team, but the effort ended in 1942, not long after the unexpected death of Coach Lenny Sachs. Only in 1944 did they have enough new players — nearly all freshmen — to play against nearby schools again, though only a few other schools could muster teams. The Loyola News student newspaper became a thinner, sparser, weekly publication as well, with less athletics to report on and fewer students on staff, and even went on hiatus from 1943 to 1944.

The war affected daily student life as well. Wartime rationing was felt at both Loyola and Mundelein, though Loyola students mostly commented on the rationing of razors, noting how they adapted their shaving habits. Students at both schools could attend war-related special lectures, volunteer for war-related activities, and see war-related ads for branches of the military or Coca-Cola in the Loyola News.

The nature of college life itself was also in flux. For men who could be drafted, being in college could exempt them from service until graduation. Loyola students noted changes in English draft laws that revoked military service exemptions for students of non-war-related subjects. Math and science students could stay in school, but those in the liberal arts were drafted into service. For Loyola students, the uncertainty of the draft must have been an ever-present possibility.

Students were not the only Loyolans questioning how the war would affect academic life. Father Hussey, S.J. spoke openly about his concerns that new federal measures aimed at preventing researchers from revealing atomic secrets would jeopardize academic freedom. Fearing that the liberal arts might lose funding, other faculty argued publicly that intellectual freedom and the study of culture were just as vital to a free society as the scientific and medical disciplines.

Soldier Students

The war created a sudden need for trained scientists and doctors, so Loyola moved to a four-quarter schedule and altered its course offerings in preparation to rush students through an intense barrage of cram courses so they could enlist and bring much-needed skills to the war front. Junior and seniors who were native-born, unmarried, and between the ages of 19-28 could enlist as U.S. Navy reserve midshipmen, class V-7 and be placed on active duty immediately after graduation. Courses included "mathematics, spherical trigonometry, elementary electricity, elementary radio, morse code, naval history, naval customs and traditions, ordnance, and naval organization."

With its proximity to Palwaukee Airport (today Chicago Executive Airport) only 18 miles away, Loyola housed U.S. Navy Air Cadets during their flight training. Loyola students could also sign up for the Naval Air Corps to help fill the demand for 2,500 new pilots each month.

Making use of its medical resources, Loyola sponsored an army hospital unit, The 108th Army General Hospital. In 1944, when it set up at The Hospital Beaujou in Clichy, France, it was said to be the largest U.S. army hospital in the world, filling eleven floors. The hospital boasted "60 doctors and dentists from the Loyola University schools of Medicine and Dentistry, 115 nurses from Loyola affiliated hospitals, and 800 enlisted men, many of whom are former Loyola students," and the chaplain Capt. George L. Warth, S.J. was former regent of the Loyola Medical School and "one of the first Jesuits to go on active duty in World War II."

Loyola was the only Catholic college to partner with the United States Armed Forces Institute during the war. Through this collaboration, American soldiers abroad could take correspondence courses from Loyola’s Home Study Division (later the Correspondence Study Division), which had previously been most popular with married women at home.

Loyola also went beyond this program’s requirements. Working with Father Achilles F. Fererri, the chaplain of Camp Hereford, a prisoner-of-war camp in Texas, Loyola offered correspondence courses to Italian prisoners of war. Fifty-four men enrolled, mostly in English courses. By offering education to these POWs, Loyola worked to meet the Jesuit mission of reconciliation between men, while also adding some unusual students to the Loyola ranks.

Women at War

While men enlisted, college women also weighed their options. If they wished to enlist, women could join the Waves or the WAACs (the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps). Many from Mundelein and Loyola did join up, while others trained in stenography and sought jobs as military secretaries. Many local women religious took flight courses through Loyola at Palwaukee to prepare to teach pre-flight courses in Chicago high schools.

Mundelein opened the first local Red Cross chapter, offering classes to prepare young women to respond to emergencies on the home front, and similar classes were offered at Loyola. This was especially important as men and women in the medical field went overseas, leaving fewer prepared citizens back home. Popular new courses in flight path reporting trained college women to report the direction, speed, and height of enemy planes to defense forces in case of an air attack on American cities.

Meanwhile, the Skyscraper student newspaper urged students to pray for peace and keep their spirits up in the name of victory, while also staying up on the latest developments. A group of art and history students painted a map in the Tea Room, which they altered based on reports of changing fronts in the war. Keeping morale up also included partnering with Loyola efforts, such as choir concerts, plays, and parties, helping to fill the stage or the dance floor while such a large part of the Loyola student body was overseas.

News From Abroad

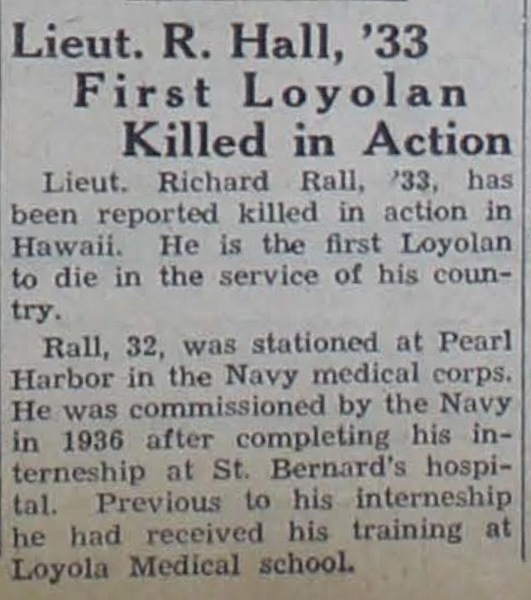

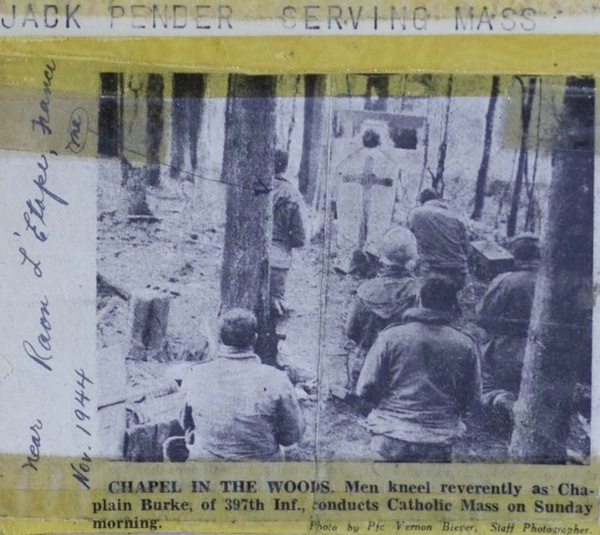

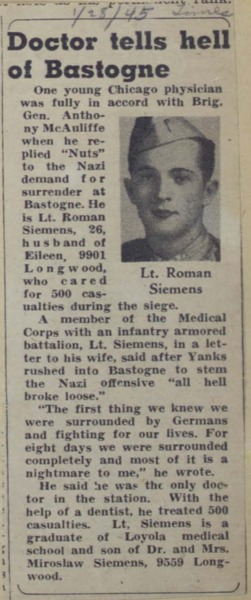

Loyola students, faculty, and alumni in the armed forces sent photos and updates from abroad. Father William A. Finnegan, S.J., dean of the college of liberal arts, collected these mementos and news clippings in a scrapbook throughout the war. His scrapbook collects the stories of students and their families, weddings, partings, reunions, acts of bravery, and tragic reports.

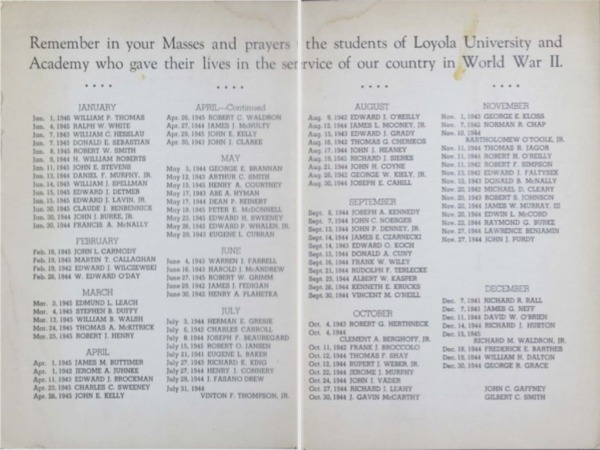

As more Loyolans went to war, news came back of fatalities. Over the course of the war, Loyola lost over 100 students. Others risked their lives and narrowly survived. Some received medals for their bravery, both as soldiers and as clergy on the battlefield, protecting their peers. In 1944, students raised funds through a paper drive to build a temporary memorial gateway at the entrance to the Lake Shore Campus, "in memory of Loyol[a]'s sons who have made the supreme sacrifice in this present world conflict." Eventually a permanent plaque was installed in the Madonna della Strada Chapel, and a memorial service was held on November 24, 1946, for all students and alumni who had given their lives in the war. Their names and photos were also collected in a memorial album.

Afterwards

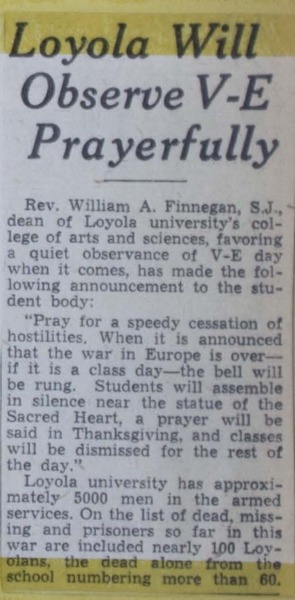

While student celebrations of the end of the war were not recorded, Loyola planned to mark V-E Day with prayer. As with many world events, Loyolans responded by gathering and praying for peace.

In many ways, life seemed to go back to normal at Loyola and Mundelein. Social activities picked up, Loyola sports teams grew, Push Ball resumed, and schools returned to their usual course offerings. However, the student body seemed more interested in international affairs, more willing to engage in debates over freedom of speech and civil rights, and more aware of their growing political voice.

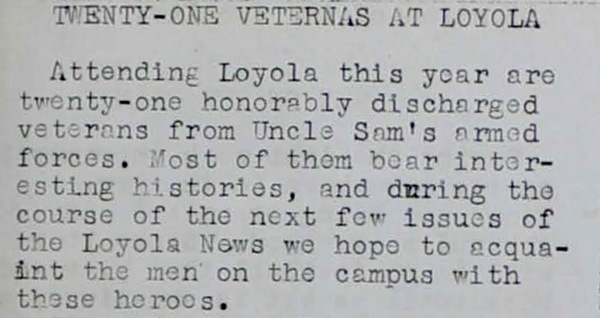

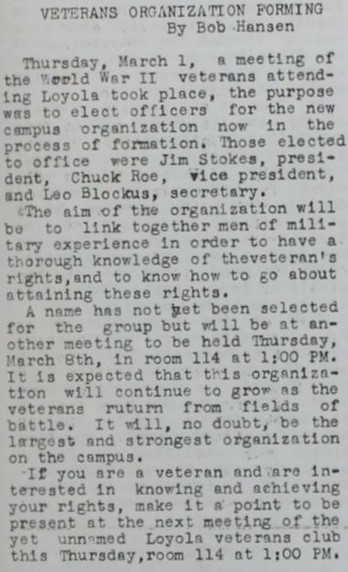

Veterans returning from the war became a noticeable group on campus even before the war's end. Twenty-one of them formed an organization in October of 1944 to educate themselves on forms of support available to them. Once the war ended, hundreds of veterans came to Loyola to earn degrees. Mundelein and Loyola veterans were interviewed for student newspapers, and their stories became part of the school’s history. Mundelein offered paths for women who wished to remain in the workforce during and after the war, while some veterans at Loyola received attention for their harrowing experiences or outspoken opinions.

In the end, World War II left a deep mark on both schools. For many students, new purpose could be found in responding to an unimaginable war, either at home or abroad. For those who went into service, very little is known of their experiences participating in world events of an enormous scale. While we may never know the full stories of students who served in World War II, these glimpses of their experiences show patterns of service, adaptation, and collaboration in the face of adversity and tragedy.

*Mundelein College, founded and operated by the Sisters of Charity of the Blessed Virgin Mary (BVM), provided education to women from 1930 until 1991, when it affiliated with Loyola University Chicago.