The Century of Progress

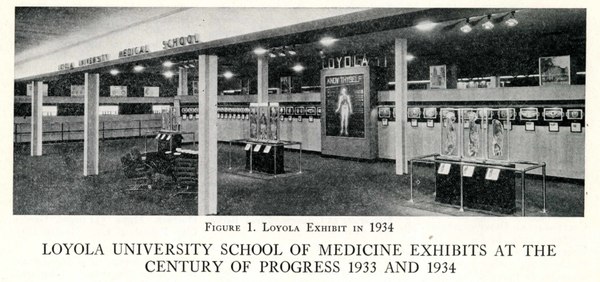

Chicago’s medical professionals did not keep to their own academic communities. At the 1933 Century of Progress, visitors viewed medical exhibits in the Hall of Science. Exhibits included the AMA’s “Medical Practice, Progress in Medical Care, Progress in Medical Education, and Progress in Health Education.” If fairgoers had stronger stomachs, they could view the exhibit curated by the Loyola School of Medicine. At the time, Loyola possessed one of the largest embryological collections in the country—primarily from donations by Loyola graduate Dr. Helen L. Button.[2] The school displayed this nearly complete collection, along with human cadavers sectioned at different angles, cases containing parts of the human body, and corresponding microscopic slides. Loyola’s exhibit attracted the curiosity of many. Today, the Loyola School of Medicine embryological collection can be seen in the Prenatal Development exhibit at the Museum of Science and Industry.

Since the mid-1800s, Chicago has been a hub of medical research and activity. Beginning with water sanitation advocacy, medical professionals in the city found ways to organize and set standards for instruction and practice. Organizations such as the AMA set guidelines for medical schools, and institutions such as Loyola incorporated these guidelines into its curriculum. In addition, the 1933 World’s Fair allowed institutions to educate the public on scientific topics and the mystery of the human body.

[2] Sara Dubow, Ourselves Unborn: A History of the Fetus in Modern America, Oxford UP: 2010, 38-39.