Setting Standards

The 1910 release of the Flexner Report put medical schools under immense pressure to raise standards of admission and education, and as a result, many schools closed for their inability to follow guidelines. The American Medical Association (AMA) continued to revise guidelines following the publication of the Flexner Report, even going so far as to publish official lists of certified medical schools across the country. In 1933, the AMA’s Council on Medical Education and Hospitals constructed the “Essentials of an Acceptable Medical School” which include the following aspects:[1]

"Organization – A medical school should be incorporated as a non-profit institution.

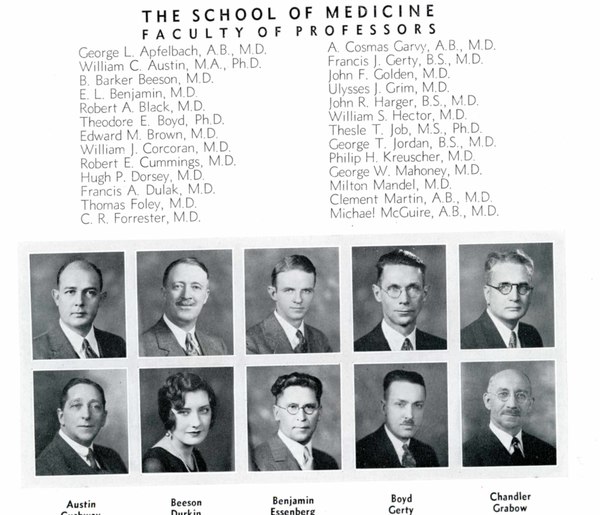

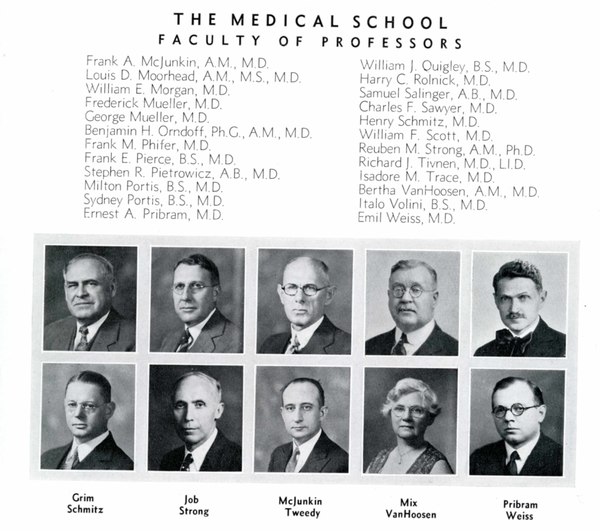

Faculty – The school should have a competent teaching staff, graded and organized by departments.

Plant – The school should own, or enjoy the assured use of, modern fireproof buildings sufficient in size to provide lecture rooms, class laboratories, small laboratories for the members of the teaching staff and advanced students, administrative offices, and a medical library.

Clinical Facilities – The school may own or control a general hospital…The school should own or control a well ordered dispensary or outpatient department with a daily average attendance of at least 100 (visits).

Resources – Experience has shown that modern medicine cannot be acceptably taught by a school which depends solely on the income from students’ fees.

Administration – There should be careful and intelligent supervision of the entire school by the dean or other executive officer who, by training and experience, is fitted to interpret the prevailing standards in medical education, and who is clothed with sufficient authority to carry them into effect.

Curriculum – Several of the medical schools now require an internship for graduation. Where it is not required it should be strongly urged and graduates should be assisted in securing internships in hospitals approved by the Council on Medical Education and Hospitals of the American Medical Association."

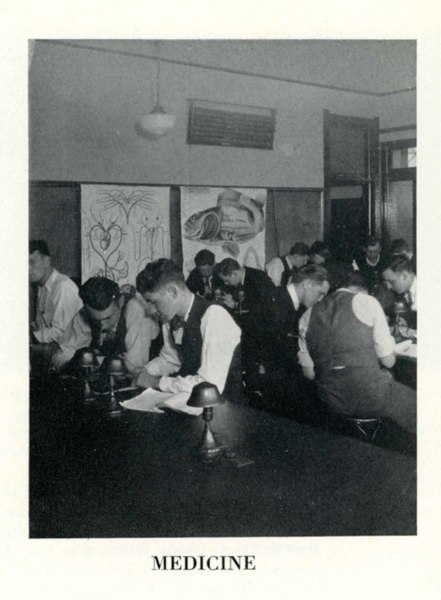

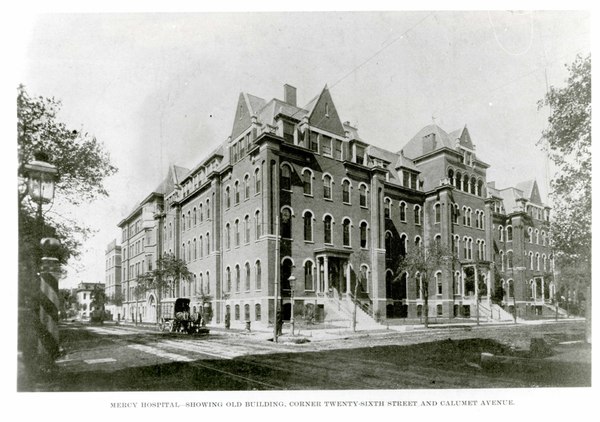

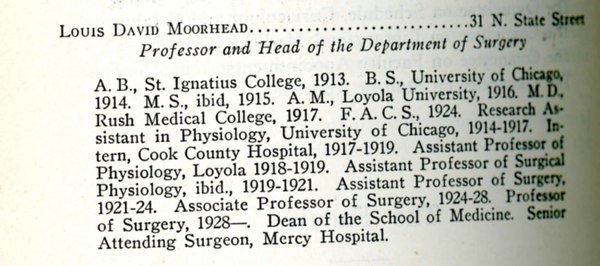

Loyola’s medical program required clinical rotations in hospitals around the city before the AMA published its list of essentials. Seniors of all Chicago-area medical schools took an exam that determined their internship placement, where the highest ranking test scores granted individuals placement at the Cook County Hospital. Other hospitals that Loyola students interned at included: St. Bernard’s, Mercy Hospital, St. Anne’s, St. Elizabeth’s, St. Mary’s, Alexian Brothers, Misericordia, Municipal Contagious Disease Hospital, and Illinois Charitable Eye and Ear Hospital. Though medical students were expected to perform rotations in hospitals before the 1930s, Chicago medical schools did not have teaching privileges in hospitals until 1931. That year, the Board of County Commissioners granted teaching privileges to medical schools at Loyola, Rush, Illinois, and Northwestern. The change staffed professors at hospitals and allowed them to bring students to a patient’s bedside for more direct instruction. With this new policy, students experienced more hands-on learning in their classes with real patient cases.

[1] American Medical Association, Proceedings of the House of Delegates of the American Medical Association (Chicago: 1933), 28-30.