Modern, Complete, and Efficient: Mundelein Center, Then and Now

Then: The Skyscraper (1929)

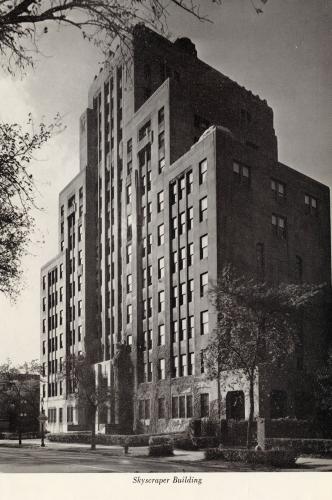

Just as the Great Depression hit, the Sisters of Charity of the Blessed Virgin Mary opened an ambitious new college on Chicago’s North Side. Mundelein College made an entrance to the world of women’s Catholic higher education with a 198-foot Art Deco structure, known then as the Skyscraper and today as Loyola University Chicago’s Mundelein Center for the Fine and Performing Arts. The fourteen-story building did more than house the entire college, however. The Skyscraper also served as a powerful symbol, its architecture reflecting Mundelein’s lofty goals of gender equality and exceptional urban, Catholic education.

Mary Justitia Coffey, BVM asserted, “it is the aim of those in charge of this institution that the quality of the instruction shall be in keeping with the exterior of the college—modern, complete, efficient.”1 Conceived as a state-of-the-art, urban, commuter college rooted in the tradition of Catholic education, Mundelein College provided opportunities for Chicago’s young women to “aim high.”2 The Skyscraper reflected this intention by design.

Joseph W. McCarthy, the preferred architect of the Archbishop of Chicago George Mundelein, envisioned a fifteen-story brick structure. The BVMs rejected this design as too expensive but kept McCarthy as the supervising architect. Meanwhile, they selected Nairne W. Fisher to design the Skyscraper’s current form.3 It was still a costly project, especially during the Depression. The BVMs mortgaged the Immaculata High School and St. Mary’s High School buildings, a risky move that secured a $500,000 for the construction of Mundelein College.4

Project Timeline

Photo Details >>

November 6, 1929

Photo Details >>

March 29, 1930

Photo Details >>

June 18, 1930

Photo Details >>

Construction began on November 1, 1929, the 96th anniversary of the founding of the Sisters of Charity of the Blessed Virgin Mary in the United States.5 Despite the global economic crisis, the Skyscraper was finished by September 1st, 1930, just in time for classes.6 The massive limestone structure was cutting-edge for its time. Very few colleges built high-rise educational buildings, but the Skyscraper saved Mundelein both space and money by building vertically rather than horizontally.7 Years after its construction, it remained the tallest building north of the Loop.8 Impressive inside and out, the Skyscraper housed everything needed for a modern college: classrooms, laboratories, meeting rooms, seven floors of living space for BVMs, and art and music studios along with a library, chapel, swimming pool, gymnasium, and cafeteria.9

Chapel

Photo Details >>

Swimming Pool, 1960

Photo Details >>

Chemistry Lab

Photo Details >>

Gymnasium, 1930

Photo Details >>

The Skyscraper also exemplified Art Deco architecture, of which Chicago was a major center. Popularized in the 1920s, the Art Deco style, like Mundelein, balanced both change and tradition by blending modern technology and established fine art.10 The Skyscraper’s design contained both modern and ancient elements, intentionally mirroring Mundelein’s forward-looking goals and Catholic roots.

Beloved by Mundelein alumnae, the Skyscraper became one of Chicago’s iconic buildings. Until 1991, when Mundelein College affiliated with Loyola, Mundelein students used the Skyscraper’s name and distinctive silhouette for the school newspaper and yearbook. As the college acquired additional buildings, including Piper Hall and Coffey Hall, the Skyscraper remained the heart of Mundelein College.

Students at Mundelein College, 1937

Photo Details >>

Now: Mundelein Center for Fine and Performing Arts (2012)

Though it now bears a different name, the life of the building once called the Skyscraper is far from over. Renovated extensively over eight years and rededicated on October 13, 2012, it is now Mundelein Center, home to Loyola University Chicago’s Fine and Performing Arts program.11 With 57 classrooms, it contains more classroom space than any other building on Loyola’s Lake Shore Campus, in addition to its practice rooms, recording studios, two theaters, and scene, costume, paint and lighting shops.12

Of course, redesigning and renovating a 74-year-old building comes with a unique set of challenges. Mundelein Center’s elevators originally did not extend to the BVM’s living quarters on the highest four floors. Now, to the relief of everyone’s legs, the elevators reach from basement to roof.13

Loyola drama students in Newhart Theater, 2012

Photo Details >>

Mundelein drama students ready to perform

Photo Details >>

The plan for a new theater, the Newhart Theater, also presented a problem. In order to take over the role of Loyola’s center stage from the Mullady Theatre in Centennial Forum, the Newhart Theater required the careful removal of three structural columns. To make up for the loss in support, an award-winning steel transfer beam now holds up Mundelein Center’s fourth through seventh floors.14 Thanks to this innovative engineering, the Newhart Theater opened in time for Loyola students to perform a one-act play, “Lake is East,” by alumnus Philip Dawkins at the 2012 rededication ceremony.15

In addition to its role as an academic and performing arts building, Loyola students today know Mundelein Center “for its ridiculously long elevator lines” and “potentially haunted 14th floor.”16 The city of Chicago has its own associations with the building and designated it in 2006 as an official Chicago Landmark. As well as for occupying a “critical part of the city’s heritage” and displaying high-quality architecture, Chicago recognizes Mundelein Center as a distinctive visual marker of the city’s North Side.17 As it towers over the Lake Shore Campus, Mundelein Center serves as a striking reminder of Mundelein’s legacy and Loyola’s present and future.

« In the Service of Others: Early and Late Diversity of the School of Medicine