Catalogue Entry: The Rüstem Paşa Cami

Rüstem Paşa Cami

Sullivan Kuhfahl

HONR 212

Professor Tomaselli

December 15, 2022

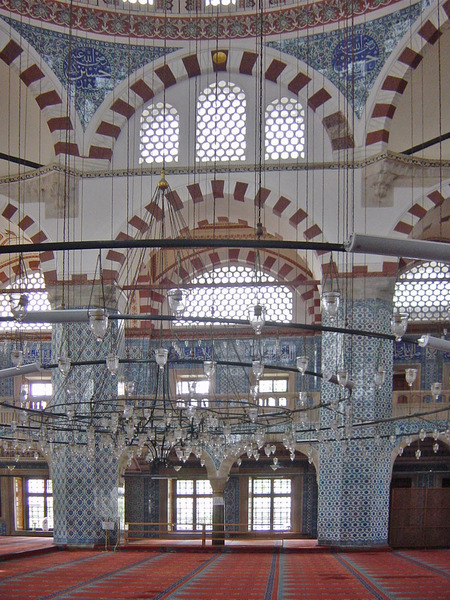

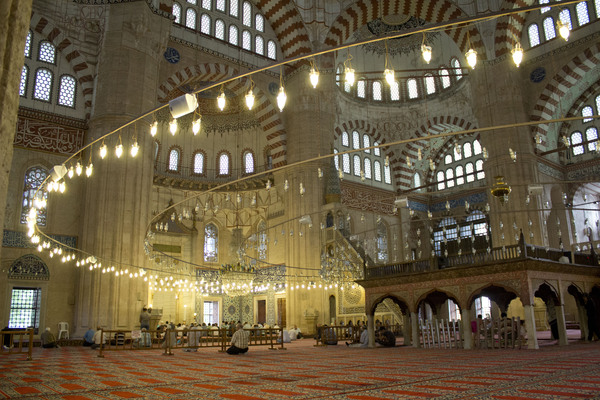

The Rüstem Paşa Cami is a mosque located in the Tahtakale neighborhood of Istanbul, Turkey.[i] The mosque, which was built upon a suspended platform and is supported by vaulting beneath it, is distinguished from its surroundings by its height and stature. Just as impressive is the interior prayer hall, known for its exquisite display of Iznik tiling. The tiles of Rüstem Paşa Cami are exceptional both in their number and in their detail.

The hues and depth of the Iznik tiles appear with their full brilliance, as the prayer hall incorporates a great variety of windows. Some panes are smaller and rounded, held in vast, neat arrays by glass grilles; others are impressive in size, such as the two tiers of large windows which crown the mihrab. Light is allowed in from every level of the interior: the doors in the entryways are inlayed with glass, and larger features span the areas framed by the arches and pendentives just beneath the dome. The gallery level has glass-fitted doors as well, in addition to semicircular planes tiled with glass circles one level above. The many entrances provided for light together flood the space and enhance it by bringing visibility to all the details and ornamentation, which extend into every far niche and crevice. [ii]

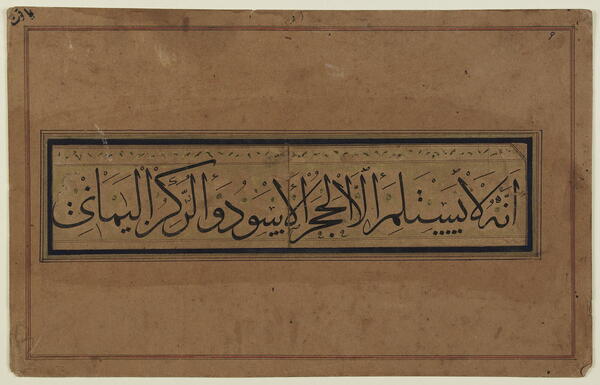

The text above the mihrab niche is an excerpt of a verse from the Quran, which reads:

So her Lord accepted her graciously and blessed her with a pleasant upbringing—entrusting her to the care of Zachariah. Whenever Zachariah visited her in the sanctuary, he found her supplied with provisions.[iii]

The excerpt featured above the niche contains only a fragment of this passage and includes the term which is translated above as “sanctuary,” but may alternatively be interpreted as “mihrab.” It is this significance which makes the verse appropriate to be positioned near the niche, as is common in mosques generally.[iv]

The aforementioned mihrab text is rendered in thuluth script, which carries historical and spiritual significance as a hand traditionally used for Quranic calligraphy. The script lends “clarity and legibility” to text, which is an especially important characteristic to have for monumental inscriptions being read from afar.[v] This script finds additional use elsewhere in the prayer hall: the “revered names” inscribed in the roundels on each of the eight pendentives are also written in the thuluth style.[vi] These circular tile roundels of the pendentives are set in tiled triangular fields of flowers and exemplify a reoccurring motif of floral tile patterns in the Rüstem Paşa Cami. The floral designs, just like the roundel inscriptions, must also be clear when being read from far away. Tile patterns, being composed of many individual tiles, can convey cohesive graphical ideas which exceed the boundaries of any one tile. Thus, the dimensions of the patterns can be extended, thereby “magnifying patterns to assure their legibility from a distance,” doing for the tilework what the thuluth script does for the inscriptions.[vii]

Together with the extensive use of glass, the vast inflows of light, and the abundance of Iznik tilework, the visual programme of the Rüstem Paşa Cami’s prayer hall is made complete by the measures taken to make its many stunning features visually accessible to its congregation: legible thuluth script and magnified tile patterns. The space can best receive the community it serves when it communicates clearly the aspects of its design which contribute to making its atmosphere a sacred one fit for worship. The ideals of accessible design applied in the prayer hall carry over to the mosque’s exterior. Although an expansive space was cleared in preparation for the construction of the mosque, large portions ultimately went unused. This space, which would typically be allotted for use as the companion garden enclosure for the mosque, was instead left open so as to preserve the activity of the preexisting streets with which the space overlapped. Additionally, the building’s planners neglected to include the precinct wall, a customary feature which denotes the point of separation between sacred and profane spaces. In planning out the relationship the finished structure would have with its neighbors, the designers made “no attempt to redefine the urban tissue” or “[isolate] the mosque from surrounding structures.”[viii] Rather, it is distinguished by the many prominent routes it takes to be inviting. Although separate from the prayer hall, the exterior of the Rüstem Paşa Cami has an equally crucial role in making the mosque a worthy worship space for its congregation, as it must invite them before the prayer hall can engage them.

The namesake and patron of the Rüstem Paşa Cami is Rüstem Paşa, who served as a grand vizier of the Ottoman Empire under Sultan Süleyman. A letter written by the Sultan reveals some aspects of the history of the site on which the Rüstem Paşa Cami was built: prior to the mosque’s placement there, it was occupied by a “small mescit.”[ix] Additionally, having been sent in the year 1562, the Sultan’s letter suggests a rough dating for the construction of the mosque of around 1560. Most of the planning and construction of the Rüstem Paşa Cami, done by the architect Mimar Sinan, occurred following the death of Rüstem Paşa; thus, “like most posthumously built structures it lacks a foundational inscription,” which makes an accurate dating challenging.[x]

The Sultan’s letter, which gives permission for the building of the mosque, justifies the authorization by “Citing a petition from [the mescit’s] congregation that requests the enlargement of the mescit and its conversion into a mosque.”[xi] The construction was legitimized by aligning with the needs and wishes of those who inhabited the surrounding neighborhood of Tahtakale. Such a charitable motivation is better understood when informed by the background of Rüstem Paşa. As grand vizier, he was enormously successful in bolstering the economy of the Ottoman Empire. However, “a frothing temper and a noted desire for wealth and power” would leave him with a sullied reputation.[xii] The mosque being built in service of community would thus contribute towards repairing the vizier’s name in addition to providing it with longevity.

The choice to plant the mosque of Rüstem Paşa where the old mescit once stood was not arbitrary. In planning for the structure to fulfill its purpose of serving its surrounding community, it was decided that the Rüstem Paşa Cami be built on the demolished plot of the mescit to take advantage of the financially valuable plot of land it sat upon. Thus, the paşa’s mosque would receive a seat at “the very centre of commercial activity at the bustling port of the capital,” and would be made into a lucrative, revenue-generating structure for its congregation.[xiii] Much of the land’s value arose from the occupied space beneath the mescit, which contained markets and warehouses. Additionally, this raised platform lets the mosque peek over the heads of the surrounding buildings, thereby distinguishing itself and its neighborhood visually from the rest of Istanbul. The masterful planning of Rüstem Paşa guaranteed that the construction which would perpetuate his name would be fully integrated—spiritually, economically, and visually—into the community he bestowed it upon.

Through time, the prayer hall has accumulated considerable damage to many of its features. Much of it arose out of restorative work which, in the opinion of the academic and author Godfrey Goodwin, has left unsightly scars. In the 19th century, the mosque was painted “wherever there was room to paint,” leaving the inside arches with “ugly false marbling.”[xiv] The mosque’s tilework sustained insult as well: tremors caused the extensively decorated north wall to drop tiles, which were either poorly put back into place, or “replaced by inferior seventeenth-century examples.”[xv] The academic Gülru Necipoğlu has written in agreement, describing the outside ablution fountain as being “very poorly restored,” having been “covered by an ungainly pyramidal roof of concrete.”[xvi]

[i] Necipoglu Gülru, The Age of Sinan: Architectural Culture in the Ottoman Empire (London: Reaktion Books, 2011), 321.

[ii] Godfrey Goodwin, A History of Ottoman Architecture (New York: Thames & Hudson, 1971), 250.

[iii] Qur'an 3:37

[iv] Necipoglu Gülru, The Age of Sinan: Architectural Culture in the Ottoman Empire (London: Reaktion Books, 2011), 330.

[v] Yasser Tabbaa, “The Transformation of Arabic Writing: Part 1, Qurʾānic Calligraphy,” in The Production of Meaning in Islamic Architecture and Ornament (Edinburgh University Press, 2021), 282.

[vi] Necipoglu Gülru, The Age of Sinan: Architectural Culture in the Ottoman Empire (London: Reaktion Books, 2011), 329.

[vii] Necipoglu Gülru, The Age of Sinan: Architectural Culture in the Ottoman Empire (London: Reaktion Books, 2011), 325.

[viii] Necipoglu Gülru, The Age of Sinan: Architectural Culture in the Ottoman Empire (London: Reaktion Books, 2011), 324.

[ix] Leslie Meral Schick, “A Note on the Dating of the Mosque of Rüstem Paṣa in İstanbul,” Artibus Asiae 50, no. 3 (1990): 286

[x] Necipoglu Gülru, The Age of Sinan: Architectural Culture in the Ottoman Empire (London: Reaktion Books, 2011), 323.

[xi] Leslie Meral Schick, “A Note on the Dating of the Mosque of Rüstem Paṣa in İstanbul,” Artibus Asiae 50, no. 3 (1990): 286

[xii] “Rustem Pasha Mosque,” Stories Ottoman Objects Tell, accessed December 13, 2022, https://mediakron.bc.edu/ottomans/rustem-pasha-mosque-1

[xiii] Necipoglu Gülru, The Age of Sinan: Architectural Culture in the Ottoman Empire (London: Reaktion Books, 2011), 323.

[xiv] Godfrey Goodwin, A History of Ottoman Architecture (New York: Thames & Hudson, 1971), 251–252.

[xv] Godfrey Goodwin, A History of Ottoman Architecture (New York: Thames & Hudson, 1971), 250.

[xvi] Necipoglu Gülru, The Age of Sinan: Architectural Culture in the Ottoman Empire (London: Reaktion Books, 2011), 324.

Works Cited

Bloom, Jonathan M., and Sheila S. Blair. The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture, s.v. “Mosque.” Accessed December 13, 2022. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009. https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780195309911.001.0001/acref-9780195309911.

Goodwin, Godfrey. A History of Ottoman Architecture. New York: Thames & Hudson, 1971.

Gülru, Necipoglu. The Age of Sinan: Architectural Culture in the Ottoman Empire. London: Reaktion Books, 2011.

Schick, Leslie Meral. “A Note on the Dating of the Mosque of Rüstem Paṣa in İstanbul.” Artibus Asiae 50, no. 3 (1990): 285-288. https://doi.org/10.2307/3250073.

Stories Ottoman Objects Tell. “Rustem Pasha Mosque.” Accessed December 13, 2022. https://mediakron.bc.edu/ottomans/rustem-pasha-mosque-1.

Tabbaa, Yasser. “The Transformation of Arabic Writing: Part 1, Qurʾānic Calligraphy.” In The Production of Meaning in Islamic Architecture and Ornament, 259-309. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2021.