Catalogue Entry: The Innsbruck Plate

Examining the circulation of Islamic gifts between the tenth and twelfth centuries, understanding the connectivity and exchange of luxurious objects, such as the Innsbruck Plate, is key to defining royal relationships across cultural and geographical divides. The Innsbruck Plate thought to have been made for Artuqid ruler of Hisn Kayfa, Rukn al-Dawla Dawud based on the Arabic inscription on the plate, has no determining point of origin, leaving room for uncertainty when defining the relationship between the giver and recipient of the gift. Despite this ambiguity, this object’s association with multiple cultural realms conveys an identity of greater fluidity based on cross-cultural communication[i] and gift-giving. Moreover, the artistic elements of the gift such as the shape, the enameling technique used, and the figural depictions on the dish reflect a network of various cultural influences, thus, illustrating community across medieval Islamic courts.

When attempting to identify the origin of the Innsbruck Plate, the shape and inscriptions[ii] of the dish offer connection to Persian cultural influences. The Innsbruck Plate is a hemispherical bowl made of a base material of copper metal. Metal dishes with rounded sides and wide foot-rings were common in medieval Persian metalwork. An object of similar shape and material is the silver, partially gilt bowl in the Keir collection [iii]in Richmond. This metal bowl displays a rounded body, a splayed foot rim, and a garbled Persian inscription. These elements present on both the Innsbruck Plate and the silver bowl in the Kier collection point to similar Persian art influences despite being manufactured 70-74 years apart. Moreover, the garbled nature of the Persian inscriptions [iv]on these objects suggests that the places of manufacture were distant to the recipients. Looking at other inscriptions on the Innsbruck Plate, the interior Arabic inscription displays the name of the Artuqid[v] ruler, Rukn al-Dawla Dawud, thus suggesting this ruler as the recipient of the gift. By identifying the individual this object was sent to, as well as the influence of Persian art tradition, further information regarding the diplomatic practices involved in the giving of the gift is revealed. Understanding that the Innsbruck Plate was most likely not made within the medieval Artuqid realm based on inscriptions and the shape of the dish, is helpful when looking further into the meaning behind the Innsbruck Plate and the message of community across courts.

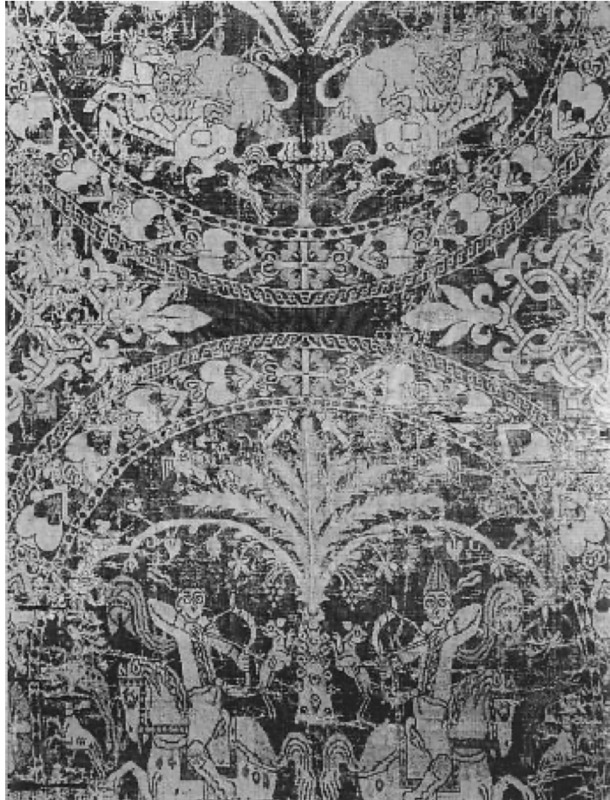

Looking beyond the inscription of Rukn al-Dawla’s name, the visual motifs present on the Innsbruck Plate act as a means of merging the recipient with the physical gift. Central to the dish, an image of a king is shown sitting on a winged griffin and is positioned as if he is about to ascend. The scene has been identified as the Apotheosis of Alexander the Great[vi], a motif used to glorify the self-image of royal individuals. This iconography can be related to the idea of reaching paradise through accession, an idea that is found in Byzantine ‘charioteer silks[vii].’ These silks, also used as eastern medieval diplomatic gifts, displayed the ascension of rulers via chariot similar to the Apotheosis of Alexander the Great imagery. These silks as well as the Innsbruck Plate can be used to understand how the gift-giver appealed to the recipient of the gift within medieval Islamic culture. By presenting the metaphorical ascent to paradise[viii], these objects represent the royal gift recipient’s aspirations for greatness relative to that of Alexander the Great. Moreover, this iconography as well as the idea of paradise beyond the Earthly realm, can be tied to the Ptolemaic planetary system[ix], which involves the separation of special material and earthly material based on the boundary between earth and the ‘supra-lunar’ world. In this sense, by presenting this image of the apotheosis, the Innsbruck Plate glorifies the identity of Rukn al-Dawla Dawud by merging his identity with that of Alexander the Great. This idea of connecting the gift recipient with the gift itself offers relevance to the idea of community across Islamic courts based on the appeal to the Artuqid ruler’s self-image that would incentivize the procession of the gift, thus, implying participation in courtly alliance with the gift-giver.

Shifting from the main image of Alexander the Great, clockwise from the head of Alexander are depictions of a peacock, feline, and bovine animal fighting, an eagle clenching a snake with its talons, and a winged horse and lion in conflict. These scenes of animal combat can be used to identify the message that is meant to accompany the Innsbruck Plate. Looking at each roundel image, the theme of dominance and submission can be identified as each scene depicts a stronger animal overpowering a weaker animal. Looking at the Innsbruck Plate relative to other medieval Islamic art pieces, a comparison can be made to the Norman Palace reception room in Palermo[x]. This reception room vault displays an eagle holding its prey in its talons referring to a message of royal victory through the representation of the Norman king. Concerning the Innsbruck Plate animal depictions, the leadership of Rukn al-Dawla Dawud can be associated with the strength of the dominant animals within the animal pairings. Moreover, these allegories of power suggest that craftsman of the Innsbruck Plate, was inspired by the regency and life of the Artuqid ruler. These aspirations reflected on the dish by the creator of the piece, allow the Innsbruck Plate to convey a message of recognition and honor to the Rukn al-Dawla, thus, expressing community across cultural boundaries.

Although the message associated with the Innsbruck Plate can be somewhat determined through the visual motifs of animal combat and the Apotheosis of Alexander the Great, the origin of the object is still left undetermined. The most prominent point of difference regarding the gift is the intact enamel of the dish. The cloisonné enameling technique[xi], which involves the layering of glass over metal objects, is commonly associated with medieval Byzantine culture, offering a potential location of manufacture regarding the gift. This enameling technique was similarly used on the crown of the Byzantine emperor Constantine Monomachos. This gift is thought to have been sent to a Hungarian princess, implying an act of community across courts in a similar fashion to the Innsbruck Plate. Despite this enameling connection to Byzantine crafts and gift-giving, a point of uncertainty when determining Byzantium as the point of production is the fact that it is unlikely that the Byzantines would send a custom gift to an Artuqid ruler based on the knowledge that the Byzantines were not allies nor threats to one another[xii]. From this understanding, another potential point of origin is Georgia, a realm that held ties to the Artuqid dynasty and used the enameling technique within its craft culture.

Taking a closer look into Georgian enamelwork, oriental motifs similar to the ones found on the Innsbruck Plate can be tied to medieval Georgian culture and can be used when determining Georgia as a possible point of origin for the Innsbruck Plate. The cloisonné and champlevé enameling techniques were relatively nonexistent within the medieval Islamic art tradition, but hold ties to Byzantium as well as the Georgian art sphere. Muslim influence over medieval Georgian culture can be linked to various Artuqid invasions [xiii]and rulings over Georgia during the late eleventh century. After Georgia regained strength and territory during the early twelfth century, Muslim influence from Artuqid rule remained in Georgian art culture through ceramics, metalwork, and textiles. One parallel that can be drawn between the Innsbruck Plate and medieval Georgian art tradition is through animal imagery[xiv]. Georgian pottery, such as a Sgraffiato ceramic dish[xv] depicting a lion, presents the animal in a similar position as the lion roundel image [xvi]shown on the Innsbruck Plate. Moreover, both this Georgian ceramic piece and the Innsbruck Plate display similar striking colors and rawness of technique. With this information relative to another potential site of the gift’s origin, the uncertainty behind the manufacturing of this object is challenged further. Once again, however, this challenge opens greater opportunity for understanding a broader network of cultural connections through diplomatic gift-giving and the means of identifying community ideas across courts.

When attempting to understand the origin, destination, and message associated with the Innsbruck Dish, no definite conclusions can be made. This ambiguity, however, acts as the foundation for creating a map of identities rather than a clear-cut medium for interaction between two courts[xvii]. The object’s ties to Byzantine, Norman Sicilian, and Georgian culture reveal information relative to a greater map of connectivity and gift-giving than a definitive exchange between one court to another world. The complexity associated with the interchange of the Innsbruck Plate offers clues to the changing relationships between different courts based on the object’s participation in bringing about allegiance and alliance between cultural realms. Moreover, the figural motifs present on the dish offer expression of power and royalty[xviii] concerning the presumed recipient of the gift, Rukn al-Dawla Dawud. Although this object’s identity is not clearly defined through its place of origin and movement, the various artistic elements of the dish including the inscriptions, animal combat depictions, apotheosis imagery, and enameling create a more expansive understanding of the dish. The various cultural influences visually present in the Innsbruck Dish highlight the dynamic nature of medieval Islamic gift-giving that in turn, offer relevance to the idea of community across courts.

[i] Redford, Scott. “How Islamic Is It? The Innsbruck Plate and Its Setting.” Muqarnas 7 (1990): 119. https://doi.org/10.2307/1523125.

[ii] Ettinghausen, Richard, and Oleg Grabar. The Art and Architecture of Islam: 650-1250. New Haven: Yale Univ. Press, 1994.

[iii] Hoffman, Eva R. “Pathways of Portability: Islamic and Christian Interchange from the Tenth to the Twelfth Century.” Art History 24, no. 1 (2001): 17–50. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8365.00248.

[iv] Ettinghausen, Art and Architecture of Islam, 204.

[v] Fuess, Albrecht, Jan-Peter Hartung, and Lorenz Korn. “Art and Architecture of the Artuqid Courts.” Essay. In Court Cultures in the Muslim World: Seventh to Nineteenth Centuries, 385–402.

[vi] Hoffman, “Pathways” 15.

[vii] Cutler, Anthony. “Gifts and Gift Exchange as Aspects of the Byzantine, Arab, and Related Economies.” Dumbarton Oaks Papers 55 (2001): 247. https://doi.org/10.2307/1291821.

[viii] Fehérvári, G. “Working in Metal: Mutual Influences between the Islamic World and the Medieval West.” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, no. 1 (1977): 3–16. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25210849.

[ix] Beyer, Vera, and Isabelle Dolezalek. “Contextualising Choices: Islamicate Elements in European Arts.” The Medieval History Journal 15, no. 2 (2012): 231–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/097194581201500201.

[x] Hoffman, “Pathways” 17.

[xi] Redford, “How Islamic Is It?” 18.

[xii] Fuess, “Art and Architecture” 390.

[xiii] Redford, “How Islamic Is It? The Innsbruck Plate and Its Setting” 19.

[xiv] Hoffman, “Pathways” 24.

[xv] Redford, “How Islamic Is It” 18.

[xvi] Beyer, “Contextualising Choices” 235.

[xviii] Ettinghausen, Art and Architecture of Islam, 203.

Bibliography

Beyer, Vera, and Isabelle Dolezalek. “Contextualising Choices: Islamicate Elements in European Arts.” The Medieval History Journal 15, no. 2 (2012): 231–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/097194581201500201.

Canby, Sheila R. Essay. In Court and Cosmos: The Great Age of the Seljuqs, 56–57. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2016.

Cutler, Anthony. “Gifts and Gift Exchange as Aspects of the Byzantine, Arab, and Related Economies.” Dumbarton Oaks Papers 55 (2001): 247. https://doi.org/10.2307/1291821.

Ettinghausen, Richard, and Oleg Grabar. The Art and Architecture of Islam: 650-1250. New Haven: Yale Univ. Press, 1994.

Fehérvári, G. “Working in Metal: Mutual Influences between the Islamic World and the Medieval West.” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, no. 1 (1977): 3–16. https://doi.org/

Fuess, Albrecht, Jan-Peter Hartung, and Lorenz Korn. “Art and Architecture of the Artuqid Courts.” Essay. In Court Cultures in the Muslim World: Seventh to Nineteenth Centuries, 385–402. London: Routledge, 2014.

Grabar, Oleg, Ghada Hijjawi Qaddumi, and Annemarie Schimmel. Book of Gifts and Rarities = (Kitāb Al-Hadāyā Wa Al-Tuḥaf): Seletions Compiled in the Fifteenth Century from an Eleventh-Century Manuscript on Gifts and Treasures. Cambridge (Massachusetts): Harvard University Press, 1996.

Harris, Jonathan, Catherine Holmes, and Eugenia Russell. “Transposed Images: Currencies and Legitimacy in the Late Medieval.” Essay. In Byzantines, Latins, and Turks in the Eastern Mediterranean World after 1150, 141–79. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012.

Hoffman, Eva R. “Pathways of Portability: Islamic and Christian Interchange from the Tenth to the Twelfth Century.” Art History 24, no. 1 (2001): 17–50. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8365.00248.

Redford, Scott. “How Islamic Is It? The Innsbruck Plate and Its Setting.” Muqarnas 7 (1990): 119. https://doi.org/10.2307/1523125.