Catalogue Entry: Tawahin es-Sukkar

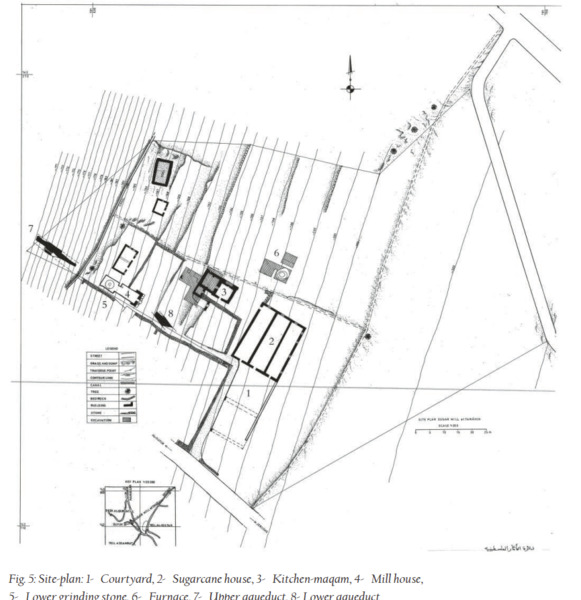

Tawahin es-Sukkar is considered one of the best-preserved sites of sugar production along the Jordan Valley. Following a series of excavations and archeological digs, the remains of Tawahin es-Sukkar were analyzed and consist of an aqueduct, a mill press and mill house, a refinery, and kitchen and mosque, a furnace, a “house of sugarcane,” and a courtyard[i]. Though these remains are not necessarily unique to Tawahin es-Sukkar, they do help researchers and archeologists understand more about medieval sugar production in this region prior to its spread to Spain and Europe[ii]. Tawahin es-Sukkar processed its sugar with manual labor and hydraulic technology, and due to the success at the mill and in the Mediterranean, experimentation for processing and refinement was common, with the only real limitation being wintertime stunting the growing season[iii].

The mill press and its wheel were housed in the mill house, which consisted of two barrel vaulted rooms, oriented east-west built in different phases[iv]. The wheel was in the first room, but as time went on, a second room was built, signifying an increase in the demand for sugar in the growing sugar industry. The remaining lower-half of the furnace at Tawahin es-Sukkar has an outer diameter of approximately four meters, and an inner diameter of 1.70 meters. The debris found within the circular furnace largely consists of ash, slag, and ceramic shards. Interestingly, signs of burning are visible on its mudbrick walls[v]. The kitchen at Tawahin es-Sukkar was an exceedingly large installation, and doubled as a mosque and was built in varying stages which are determined by the different construction techniques found within the remains of the site[vi]

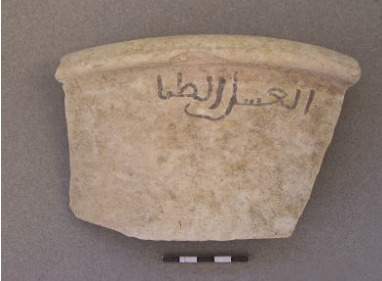

Researchers can determine that Tawahin es-Sukkar was constructed sometime in the 12th century during the Ayyubid-Mamluk period with the help of the remaining shards from ceramics, jars, and pots, as well as coins, lamps, and other domestic ware[vii]. Tawahin es-Sukkar’s presumed construction also aligns well with the growing sugar industry in the Mediterranean caused by the Arab agricultural revolution[viii]. Some of these remains, such as the lamps, have Mamluk period geometric designs and are homogenous in shape. Many of them have a polo-stick motif or a al-Jokendar which was commonplace during the Mamluk period and found on many ceramic objects in Palestine[ix]. On two shards from conical jars, there are Arabic inscriptions noting daily sugar production. Both shards essentially say “honey,” with another listing a day and number of kettles filled. In many Medieval Arab sources, sugar was deemed a “sister” to honey, with sugarcane often being referred to as “honey reeds” [x].

As the sugar industry continued to grow, the Mediterranean was considered one of the best places to grow and process sugar. This is due to the Jordan Valley and the Mediterranean coastline’s incredibly fertile landscape, perfect for growing sugarcane. Because of the conditions, there were very few regions in the Mediterranean that did not have some sort of dedicated space for growing and processing sugar[xi].

While whoever officially commissioned and constructed Tawahin es-Sukkar is unknown, it has been established that the farm workers who pressed and processed sugarcane for commercial markets were hired laborers from surrounding villages, brought in to work the surrounding farmland the mill resided on[xii]. In fact, because of the spread of sugar due to the Arab agricultural revolution, economic incentives and irrigation deals were established. Farmers who gave five percent of their produce were assisted by tax regimes with advanced irrigation practices. Those who did not agree to these taxes had to continue with standard gravity-irrigation and had to give up fifty percent of their produce[xiii]. These practices, along with an increase in labor techniques eventually led to a rise in sharecropping[xiv].

In relation to “dining,” Tawahin es-Sukkar and, subsequently, most medieval sugar mills are responsible for the mass commercialization and spread of sugar into everyday Islamic society and cuisine. Due to the mass trade of sugar, everyday foods, drinks, as well as sweets in Islamic society now have the capacity to be modified with sugar. Luxury foods consumed by wealthy Islamic elites and royalty were always sought after[xv]. For a while, sugar was inaccessible and utilized in special practices by Caliphs for the commonfolk to gaze upon in awe[xvi], but because sugar mills revolutionized the sugar production process, sugar became a key facet of dining for the wider society.

The sugar mills that processed sugar after Arab agricultural revolution brought forth a new, everlasting current of sugar usage in Islamic cuisine and the wider society. Without sugar, cuisine would lack an ere of luxury and mystique that enveloped the rich and powerful elites of Islamic society[xvii]. But aside from the wealthy, sugar had made its way into festivals and holidays like Ramadan and Eid al-Fitr, and food for everyday citizens, becoming a staple in numerous dishes[xviii]. Sugar was able to toe the line between luxury and normalcy and subtly connected people of various classes through cuisine culture.

[i] Hamdan Taha, “The Sugarcane Industry in Jericho, Jordan Valley,” in The Origins of the Sugar Industry and the transmission of Ancient Greek and Medieval Arab Science and Technology from the Near East to Europe, ed Konstantinos D. Politis (Athens: National and Kapodistriako University Athens, 2015) 54.

[ii] William D. Phillips, “Sugar in Iberia.” In Tropical Babylons: Sugar and the Making of the Atlantic World, 1450-1680, edited by Stuart B. Schwartz, 27-41. University of North Carolina Press, 2004. 31.

[iii] J. H. Galloway, “The Mediterranean Sugar Industry,” Geographical Review 67. No. 2, (1977). 183.

[iv] Politis, The Origins of the Sugar Industry, 61-63.

[v] Politis, The Origins of the Sugar Industry, 57.

[vi] Politis, The Origins of the Sugar Industry, 62.

[vii] Politis, The Origins of the Sugar Industry, 63-69.

[viii] Galloway, “Mediterranean Sugar,” 184.

[ix] Politis, The Origins of the Sugar Industry, 68-69.

[x] Politis, The Origins of the Sugar Industry, 63.

[xi] Galloway, “Mediterranean Sugar,” 181.

[xii] Galloway, “Mediterranean Sugar,” 189.

[xiii] Graham Chandler, “Sugar, Please,” Aramco World. Volume 63, No. 4, July/August 2012. 40.

[xiv] Chandler, “Sugar, Please,” 40.

[xv] David Waynes, “‘Luxury Foods’ in Medieval Islamic Societies,” World Archeology 34, No. 3., 2003. 574.

[xvi] Tsugitaka Sato, “Sugar and Power: Festivals and Gifts from Royalty” in Sugar in the Social Life of Medieval Islam. Boston: Brill, 2015. 58-59.

[xvii] Waynes, “Luxury Foods,” 574.

[xviii] Habeeb & Muna Salloum, Leila Salloum Elias. Sweet Delights from a Thousand and One Nights: The Story of Traditional Arab Sweets. London: I. B. Tauris, 2013. 3.

Bibliography

Chandler, Graham. “Sugar, Please.” Aramco World. Volume 63, No. 4, July/August 2012.

https://archive.aramcoworld.com/issue/201204/sugar.please.htm

Galloway, J. H. “The Mediterranean Sugar Industry,” Geographical Review 67. No. 2 (1977).

https://doi.org/10.2307/214019.

Phillips, William D. “Sugar in Iberia.” In Tropical Babylons: Sugar and the Making of the Atlantic World, 1450-1680,

edited by Stuart B. Schwartz, 27-41. University of North Carolina Press, 2004.

https://doi.org/10.5149/9780807895627_schwartz.6.

Salloum, Habeeb, Muna Salloum and Leila Salloum Elias. Sweet Delights from a Thousand and One Nights: The Story of

Traditional Arab Sweets. London: I. B. Tauris, 2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9780755694341.0008

Sato, Tsugitaka. “Sugar and Power: Festivals and Gifts from Royalty,” in Sugar in the Social Life of Medieval Islam.

Boston: Brill, 2015.

Taha, Hamdan. “The Sugarcane Industry in Jericho, Jordan Valley,” in The Origins of the Sugar Industry and the

transmission of Ancient Greek and Medieval Arab Science and Technology from the Near East to Europe, ed

Konstantinos D. Politis (Athens: National and Kapodistriako University Athens, 2015).

Waynes, David. “‘Luxury Foods’ in Medieval Islamic Societies,” World Archeology 34, No. 3.,2003.

http://www.jstor.org/stable/3560205.