Catalogue Entry: Goose-Shaped Aquamanile

Of the multiple surviving aquamanile, the one currently on display is an aquamanile styled in the shape of a goose. As these pieces very rarely have any marking on them noting the name of an owner or creator, and the most we can discern about their past is that it was made roughly in the twelfth century in Iran. The creation is made with a type of copper alloy, with various visible signs of wear and tear. Despite this, however, we can still see the original color scheme of the creation, with various parts of it’s body painted a deep red and the supposed eyes of the goose painted a bright turquoise.

The casting process for such a piece is likely done through a specific method that allows for gas to be dissolved into the molten metal while it cooled, which let the creators of this object carve detailed and ornate patterns all throughout it’s body[I]. Various carvings across the body take the form of other various things in nature as well, including a peacock inside a medallion around the tail and various depictions of deer around the neck and thighs. This same process, however, allowed for the metal to wear over time and become more and more rough in both appearance and shape[I].

The piece is important to consider in this medium because it is in many ways the quintessential example of an aquamanile seen around Islamic dining tables that the host of the house would use to serve his guests while showing it off to their guests as an important art piece.

Another aquamanile, fashioned in a very similar design to the aquamanile mentioned previously, is an aquamanile fashioned in the shape of a dove, pictured here. This aquamanile’s origins and background context remain fairly mysterious to studies, but we have been able to tell that it’s creation date was in between 1085 and 1115 CE and that it’s creation involved a bronze cast, judging by the work and carvings in the bird itself. The design itself is also remarkably similar to the goose mentioned above, with a half-oval band connecting the feet to keep balance and a concave space where the eyes are to hold glaze of a different color than the rest of the body. These eyes and colors have been lost with time, but it is still a prominent example of what the average aquamanile would look like for many who requested to have such a thing in their homes, both for purposes of using it and showing off to guests while eating[IV].

In addition to these pieces, there have been other aquamaniles found from around the same time that can help us discern the importance of Islamic dining these creations. One of them is another aquamanile in the form of a feline, which is also from Iran and was created in the early thirteenth century, a few decades after the aquamanile in the shape of a goose. This piece is also larger than the previous example by a fairly large margin. It is painted over with a type of glaze, with the original body being made of stone. Large bowls also hang on the back of the feline, with a tall and thin one taking up the back. Unlike the previous aquamanile as well, much of the color and decorations on the creation have been removed by time and irridescence. This piece, being larger than it’s smaller counterpart, would likely be seen at the dinner table for the same effect, if under a different situation. Judging by the bowls upon its back, this aquamanile would have also been used as a kind of fountain, in addition to being a vessel to pour water from. It provides the services an aquamanile would provide in this culture, which is primarily providing water and displaying the owner’s wealth, but is able to do so completely differently than the other aquamanile we have examined so far, highlighting the extensive variety these pieces can come in.

The fourth piece in this collection is one that is quite interesting in it’s make and model, as it denotes a high level of quality and craftsmanship. So much so, in fact, that an aquamanile of it’s kind is usually only reserved and created for those near the top of Middle Age Islam’s social hierarchy[V]. Fashioned after a lerge bird of prey, most likely an eagle, this aquamanile was made earlier than the other two examples previously mentioned, around the year 800 CE by the Abbasids, but keeps many of the same themes of luxury and splendor seen in the other two pieces. The level and style of casting denotes a high level of craftsmanship by the creator, with intricate carvings denoting various flowers across the body and head of the bird.

The aquamanile itself has received some damage before being discovered by archaeologists, including a missing piece on the back, but this damage is minimal compared to other pieces examined thus far.

This example is much more ornate than the other aquamanile we have seen, and while the people showcasing this creation would be of an undoubtedly high status, they would still use this eagle for very similar purposes.

Even in the highest levels of this era, aquamanile were seen around the dining table as a hallmark of status and power.

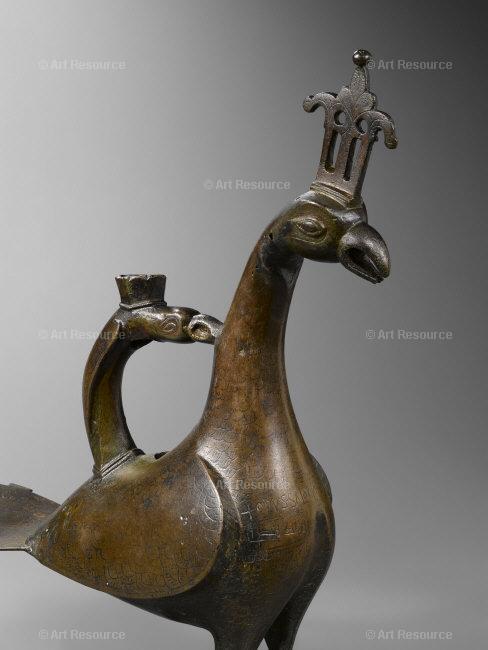

In addition to these other examples, which have been primarily aquamanile that represent birds and other various winged creatures, we have a similarly themed creation in the shape of a peacock. This specific aquamanile we do have enough information to know for sure what year it was created in, which was 972 CE. The work is yet again a cast bronze metal fashioned to fit the animal’s shape, and is roughly the same size as the eagle mentioned in the previous page.The peacock is standing atop a rock, and is the first aquamanile we have seen so far that is wearing any kind of clothing; in this case, the peacock is wearing some type of hat that is reminiscent of a crown. This aquamanile, also like the aforementioned eagle, is of a metallic structure, and lacks the use of glaze or paint in it’s creation[I].

While we many not know the exact details of how it was used or who it was used for, the details we can glean from it’s metalwork and it’s design point it towards also being an aquamanile used by an elite ruling class in Islamic culture[VI]. The design of it standing on the rock and wearing clothing points it towards a regal stature, and it is very likely the commissioner of this piece wanted something that reflected a royal presence and a connection to paradise, much as the peacock itself does in Islamic culture[II].

Bibliography

[I]Allan, James W., and Ruby Kana'an, (2017-06-20), Flood, Finbarr Barry; Necipoğlu, Gülru (eds.), "The Social and Economic Life of Metalwork". In A Companion to Islamic Art and Architecture, edited by Finbarr Barry Flood and Gulru Necipoglu, 453-477. Hoboken NJ; John Wiley & Sons, Inc

[II]Barnet, Peter. “#72: Aquamanile in the form of a cock.” In The Cloisters: Medieval Art and Architecture. Edited by Peter Barnet and Nancy Y. Wu, pp. 108, 196. New York and

New Haven: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2005.

[III]Kröger, Jens., Hagedorn, Annette., Shalem, Avinoam. Leiden, Brill. Facts and Artifacts in the Islamic world: festschrift for Jens Kröger on his 65th birthday.

2007.

[IV]Rosser-Owen, Mariam. "Mediterraneanism: How to Incorporate Islamic Art into an

Emerging Field." Journal of Art Historiography 6: (2012) 1-33. https://flagship.luc.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/mediterraneanism-how-incorporate-islamic-art-into/docview/1021054392/se-2.

[V]Schroeder, Eric. “An Aquamanile and Some Implications.” Ars Islamica 5, 8–20. 1938

[VI]Wixom, William D., Donald F. Gibbons, and Katherine C. Ruhl. “A Lion Aquamanile.” The

Bulletin of the Cleveland Museum of Art 61, no. 8 (1974): 260–70. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25152542.