Grand Bazaar Catalogue

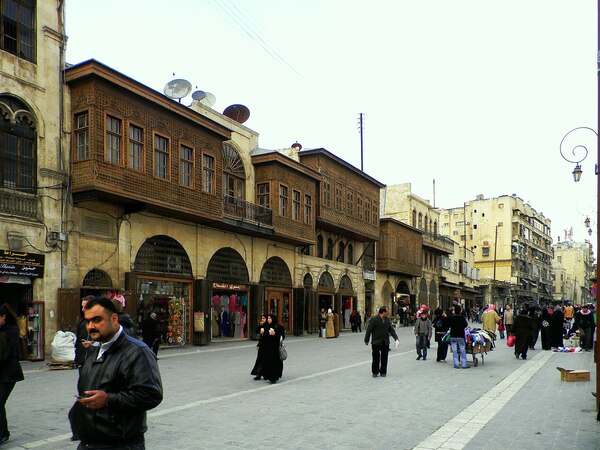

The Grand Bazaar is located in modern day Istanbul in the country of Turkey. It is a large shopping center that offers a wide range of goods and services and has been an influential part of the Istanbul and Turkish economies from the Bazaar’s inception in the mid 1400s to even this day. The Bazaar is a unique and important shopping center since it has one of the largest volumes of shops and foot traffic in all of the Islamic world. Along with this development came the unique architecture of the Grand Bazaar of Istanbul. This architecture has been the inspiration for the architecture found in other bazaars in the Islamic world. The Bazaar is also unique for its specific and purposeful urban planning which was evident before its later more disorganized structure. At the core of the Grand Bazaar’s architecture has always been the bedesten, which refers to a structured and covered marketplace. Here, according to Professor Nilufer Onay of architecture at the Polytechnic University of Turin, the most valuable and precious goods being sold and traded were stored here. The strong stone walls of the bedesten were an architectural design intended to give the most security to the goods in minds of shoppers. Likewise, we see similar architectural techniques and patterns with other famous bazaars in the Islamic world, such as the covered bazaar in Aleppo, Syria [1]. The bazaar of Aleppo also had a centered bedesten similar in function and utility as the bedesten found in the Grand Bazaar of Istanbul.

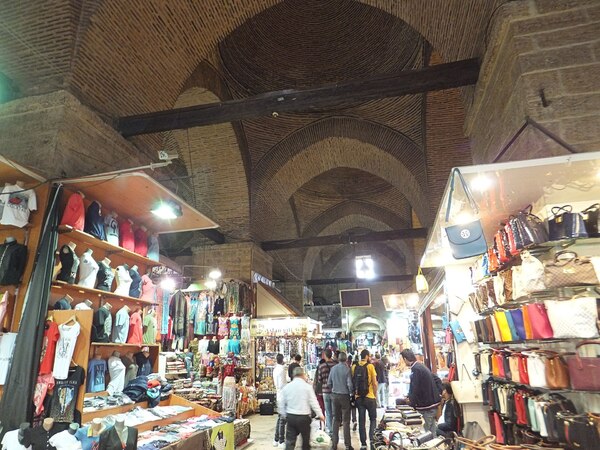

The architectural design of the Grand Bazaar was extremely significant and crafted with an astute attention to detail. Mehmed II created his architectural theme of grandness and splendor by having the bedesten fitted with massive stone vaultings. In addition, Mehmed II wanted the Grand Bazaar’s first bedesten to mimic the architectural structures of mosques. Therefore, he had the bedesten designed with domed roofs. These domed roofs are structurally supported by sets of pillars and columns, also taking inspiration from other mosque architecture and design [2]. Besides creating a feeling of security, the architecture details were practical. The bedesten was intentionally designed with four doors, one on each of the walls, that would help direct foot traffic and prevent any bottle-necking of shoppers who moved in groups. These main doors acted as the entrance to road arteries of sorts. The hall design of the bedesten allowed shoppers and merchants to pass effectively from the central bedesten to the main streets and offshooting roads, each lined with stalls and shops of differing wears and goods [3]. This Grand Bazaar became a rather efficient shopping center bringing people together safely. The Bazaar therefore enhanced the economic and practical purposes of the city of Istanbul.

The Bazaar’s architecture was the vision of its patron, Sultan Mehmed II, known as the Conqueror. When erecting this massive marketplace, Mehmed II began by first developing the base of the first of two bedestens in the location [4]. The actual construction of the bazaar speaks volumes to the kind of society and culture that Mehmed II looked to foster and impress upon his people. It was in the context of the rapid and eventful decline of Byzantium in the mid-1400s that Mehmed II constructed the Grand Bazaar and the two bedestens. In an effort to have a physical manifestation of the conquering power of not only himself, a physical and central location for trade and commerce in his empire, Mehmed II also wanted to demonstrate the superiority of Islam as a faith system. The first bedesten of the Grand Bazaar was constructed and planned on uneven land, and not on top of a pre-existing church or shopping infrastructure thereby demonstrating the originality of Mehmed’s vision and desire to build [5]. The construction of the first bedesten could be viewed as a tangible assurance to the people of his empire and as a reminder to travelers that Mehmed II as sultan was powerful and Islam was supreme.

There have been questions, and controversy, throughout the scholarship on the origin of one particular object in the first bedesten of the Grand Bazaar. The first and historically older bedesten that was constructed in the Grand Bazaar is entirely Turkish in architecture and design, with rounded domes and mimicking other Islamic market architecture found in Burma and Edirne. However, a relief of an eagle exists above one of the gates and is in the style of the double eagle crest found throughout Byzantium [6]. Controversy, therefore, arose when some scholars used this relief of an eagle to justify that the bedesten was actually Byzantine in origin, and not an entirely unique Islamic construction by Mehmed II. However, this is a wrong interpretation, and one that significantly downplays the importance of Mehmed II and his contributions to the city and the bazaar. The presence of a Byzantine style eagle relief on a Turkish structure and Turkish designed gate door is not enough to conclude that the structure is itself Byzantine in origin. Instead, the presence of the Byzantine eagle relief suggests to modern scholarship that it was a purposeful inclusion to show to the community that the Islamic rulers were tolerant of others in the community. The fact the relief remained in a prominent location proves it was not simply overlooked or disregarded in construction, but was intentionally displayed [7].

The Grand Bazaar played a very important role for the city of Istanbul and the regional economy. Istanbul is situated at a very convenient and strategically important location, so the construction of the Grand Bazaar here would have made a great deal of sense to Mehmed II. Istanbul sits nestled between many important trade routes and crossroads that connect the European and Asian regions, which made Istanbul the beating heart of the economy of Mehmed II’s empire [8]. Amid the crisscross of routes, Mehmed imposed a sense of control and order through the Bazaar’s architecture. Furthermore, the multitude of traders were organized into a guild system. With innumerable amounts of merchants gathered at the Grand Bazaar the guild system provided these merchants with not only a sense of community around their craft, but also security and a welfare system of sorts. The Grand Bazaar as a location fostered healthy competition in the marketplace and therefore, increased the economic and regional influence of Mehmed II and his Islamic empire. While there were times of strife between members of the differing Abrahmaic faiths, the economic bulwark of the Grand Bazaar and its urban planning - the different sectors and distinctions coupled with the social fabric provided by the guild system - led to a mainly cooperative understanding between Christians, Jews, and Muslims [9].

Bazaars have always been linked to Islam and the importance of the mosque in the Bazaar’s city. One of the main contributing factors to the development and continued sponsorship of bazaars, such as the Grand Bazaar in Istanbul, was its mission to provide money towards the upkeep of mosques in the city. Islamic merchants, acting through their respective guild, would provide to the local governance a “waqf”, which was a special type of donation towards the Islamic religious leaders and the mosque in the city [10]. To further emphasize the link between mosque and Bazaar, the actual urban planning of the bazaars would take into account the presence of a mosque. The main goal of the urban planning in many Islamic cities was to contain foot traffic and facilitate it towards the mosque and city center [11]. Intentionally designing both the city and Bazaar this way would allow the bazaar and the mosque to develop a symbiotic relationship with one another.

Like the bazaar of many Islamic cities, the Grand Bazaar heavily contributed towards a sense of community in Istanbul at large. Yet, in some respects it was in its own way a micro community [12]. It would not be unfair to say that the most social place in the heart of any Islamic city would be the bazaar. It would be at the bazaar where many people would gather and share in shopping or eating, or even selling their goods as was documented with the guild system in the Grand Bazaar. With this unique social aspect of the bazaar people of different economic and social classes would gather. The Grand Bazaar’s social scene became a reflection and mirror of the larger Islamic community and the city of Istanbul. As Çelik Gülersoy intelligently summarizes in his work Story of the Grand Bazaar, “At all times the Bazaar traffic has been a fashion show of Istanbul. A natural show with no ostentation, expenses, or organization… And this daily fashion show reflects the Istanbul of that day, that year, that age with its characteristics, colours, tastes, riches and poverties” [13]. The architecture of the Grand Bazaar enhanced this sense of community, especially when taken in the context of commerce and exchange of goods. By itself the transactions that make up a marketplace have no personality. There is no feeling or emotion inherently associated with the exchange. However, the architecture can begin to create values for commerce conducted within its walls. A Frenchman writing his observations of the architecture of the Grand Bazaar discusses how the actual building designs and architectural techniques used gives the whole market a sense of social cohesion and community. The Frenchman, whom Gülersoy does not name, writes that “But those very tall Gothic arches, the semi-light which surrounds… the thousand and one alleys of this Market labyrinth…” and that if an individual wants “...to go into their privacy, deeper into their lives, you ought to wander around in the Bazaars.” [14]. It is most evident that the Grand Bazaar takes on a life of its own in its architecture that in turn fosters a sense of community in the Islamic city.

Endnotes

1. Mohammad Gharipour, The Bazaar in the Islamic City: Design, Culture, and History (Cario: The American University in Cairo Press, 2012), 353-354, iBook.

2. Metin And, Istanbul in the 16th Century: The City, The Palace, Daily Life (Istanbul: Akbank, 1994), 82.

3. And, Istanbul 16th Century, 83.

4. Çelik Gülersoy, Story of the Grand Bazaar. (Istanbul: Istanbul Kitapligi Ltd., 1980), 8.

5. Gülersoy, Story of the Grand Bazaar, 8.

6. Attila Özbey Istanbul: the Grand Bazaar: from past to present. (Istanbul: Istanbul Chamber of Commerce, 2010), 37.

7. Özbey, Istanbul: the Grand Bazaar, 38.

8. Bator, Daily Life in Ancient and Modern Istanbul (Minnesota: Minneapolis Runestone Press 2000), 40.

9. Bator Daily Life, 40.

10. Gharipour, The Bazaar, 63.

11. Saglar Onay Nilufer, “Changing Shopping Spaces in Istanbul,”World Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities, 3, no. 3 (2017) 57-58.

12. M. W. Wolfe “The Bazaar at Istanbul,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, 22, no. 1 (1963).

13. Gülersoy, Story of the Grand Bazaar, 52.

14. Gülersoy, Story of the Grand Bazaar, 54.

Bibliography

And, Metin. Istanbul in the 16th Century: The City, The Palace, Daily Life. Istanbul: Akbank.

1994.

Bator. Daily Life in Ancient and Modern Istanbul. Minnesota: Minneapolis Runestone Press,

2000.

Gharipour, Mohammad. The Bazaar in the Islamic City: Design, Culture, and History. Cairo:

The American University in Cairo Press, 2012. iBook.

Gülersoy, Çelik. Story of the Grand Bazaar. Istanbul: Istanbul Kitapligi Ltd., 1980.

Nilufer, Saglar Onay. “Changing Shopping Spaces in Istanbul.” World Journal of Social Sciences

and Humanities, 3, no. 3 (2017): 56-60. doi: 10.12691/wjssh-3-3-1.

Özbey, Atilla. Istanbul: the Grand Bazaar: from past to present. 2010.

Wolfe, M. W. “The Bazaar at Istanbul.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 22, no.

1 (1963): 24–28. https://doi.org/10.2307/988208.