Catalogue Entry: Folio Painting Depicting the Scene of Mourning over the Death of Iskandar

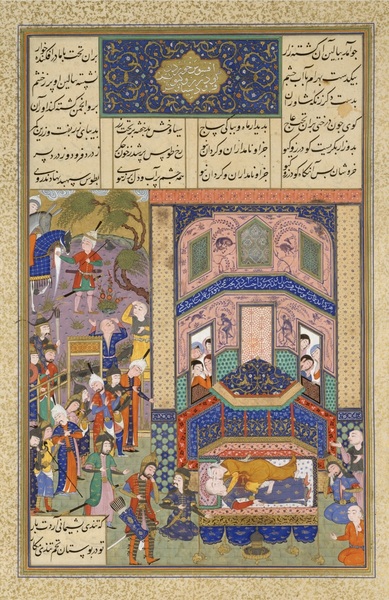

At first glance, the folio painting, see left, that depicts the scene of mourning over Alexander the Great — referred to as Iskandar in the Islamic world — appears rather cluttered. For starters, one may not even realize that the scene of mourning is for Iskandar, much less understand the significance his death had on the community. Yet, upon further review, one finds symbolic details in this approximately fifty-eight-centimeter by forty-centimeter painting: illustrated with ink, opaque watercolor, and gold, on paper. Most notably, one is immediately drawn to the prominent depiction of grief throughout the painting. The intense grief of Iskandar’s mother, who is shown flinging herself onto his coffin, and of the famous Greek philosopher Aristotle, who is shown weeping in the background, stand out to the viewer when looking closer at the painting. The lavish interior setting and the plethora of mourners sick with grief demonstrate how great an impact Iskandar’s death had on the Islamic community.

It all starts with the Shahnama of Firdawsi: a Persian epic containing hundreds of chapters[i] that detail the lives of fifty generations of kings dating back to the mythical beginning of Iran until the end of the historical Sasanian period in the year 651. It is estimated to have been completed at the beginning of the eleventh century, around the year 1010.[ii] Numerous manuscript copies of the Shahnama have since been produced and a considerable number of them have been illustrated; the folio painting depicting the scene of mourning over the death of Iskandar is within the group of early illustrated Shahnama manuscripts that can be attributed to the Ilkhanid period (1258–1353), during which the Mongol Ilkhans ruled Iran and Iraq.[iii] Specifically, this folio painting is illustrated in The Great Mongol Shahnama, one of the many illustrated manuscripts of Firdawsi’s Shahnama, but one that is considered among the earliest and most magnificent of all illustrated manuscripts to survive to this day.

The stylistic characteristics of The Great Mongol Shahnama suggest that it was produced in the 1330s, in Tabriz, Iran, under the Ilkhanid dynasty during the Mongol period.[iv] This is assumed largely in part due to how luxe it is, “with its sheer number of folios and paintings and a broad range of pigment colors including gold and silver”.[v] Additionally, the quality of “artistic representation and composition speaks for its close association with the Ilkhanid court workshop.”[vi] The process of illustrating manuscripts in Iran was quite unique as well; calligraphers first transcribed the text, leaving designated spaces for the painters to add their paintings. In the case of The Great Mongol Shahnama, “the calligraphers often indicated what was to be illustrated by writing the titles of paintings in bold letters above the painting spaces.”[vii] It was a unique process that becomes even more complex when examining the manner in which the artist painted the scene of mourning over Iskandar.

Unlike the other scenes of mourning present in The Great Mongol Shahnama, information regarding the entire setting of the scene is not on the folio of this painting. As previously mentioned, the titles of the paintings were often given by the calligraphers so that the painters would know what to paint. In addition to this, the painters could also refer to the texts already written on the folios. In the case of the painting depicting the scene of mourning over Iskandar, however, the painter did not have full textual information of the scene. The text on this folio starts with detailing the lament over Iskandar, then describes the wailing of Iskandar’s mother and wife, and ends with Firdawsi’s conclusion to the Book of Iskandar.[viii] Nothing of the actual setting — depicted in the Shahnama as an exterior setting on the plain of Alexandria[ix] — is written on this folio because, “the painting space fell into a recto without the preceding verses on the Alexandrian plain.”[x] Considering the lack of information at their disposal, the way in which the painter created such a painting is hence subject to various different interpretations.

Scholar Masuya Tomoko believes the painter “followed the text available on the folio as far as he could and worked around the missing information by depicting contemporary funerary customs in the first half of the fourteenth century when the Ilkhans were Muslims.”[xi] Such customs have been referenced by scholar Sheila Blair when examining ancient Islamic funerary practices. For example, Blair references endowment deeds for important Islamic members of society at the time, such as Rashid al-Din, who was a statesman, historian, and physician in Ilkhanate Iran. She cites how the endowment deed for Rashid al-Din at his tomb complex at Tabriz (where the scene of mourning over Iskandar folio was eventually painted), would have been a common funerary practice at the time.[xii] Blair then relates this back to the painting depicting the scene of mourning over Iskandar, citing how, in the painting, the room has a tiled dado surmounted by white walls with blue painted ornaments, and the cenotaph is surrounded by four large candlesticks: elements that are all exactly as described in the endowment deed for Rashid al-Din’s tomb in Tabriz. Blair also notes how the painting gives a good idea of how tombs were regarded in the Ilkhanid period, citing “mourners clustered around the richly decorated cenotaph, which is surrounded by candlesticks and hanging lamps along with rich furnishings including rugs, mats, and textiles.”[xiii] These are all types of decorations used in Muslim tombs of the time, and paired with the common knowledge of funerary practices at the time — while also considering the lack of textual information regarding the scene — perhaps these are examples of the painter incorporating contemporary funerary elements into the painting to fill in the blanks.

While the artist behind the folio painting depicting the scene of mourning over Iskandar is unknown, what is known is that it was painted by someone with extraordinary talent. Scholars Oleg Grabar and Sheila Blair cite the “complexity of the directions of gaze leading to and from the hero’s bier as well as a variety of axes of movement and order”,[xiv] as elements that could only have been imagined and executed by a painter of great talent. Additionally, detailed facial expressions and intentional peculiar features, such as the long finger of one of the mourners, the flowing robe of Iskandar’s mother, and attempts to show textures and layers of clothing, such as veils, are all cited as further demonstrations of the painter’s talent.[xv] Illustrating these manuscripts was clearly a unique process, but the reasoning behind illustrating stories from the Shahnama is even more unique.

As previously stated, Firdawsi’s Shahnama was completed at the beginning of the eleventh century, around the year 1010, but illustrations in The Great Mongol Shahnama — such as the folio painting of the scene of mourning over Iskandar — were completed in the 1330s, over 300 years later. Likely, this was due to the establishment of Mongol rule through the Ilkhanid dynasty at the time.[xvi] While the Mongol invasions of Iran during this time are well-documented, scholar Oleg Grabar points out how the new rulers of Iran, which included the Ilkhans, spent a lot of time and money economically reconstructing the land to fit their system.[xvii] In “a world the Mongols were beginning to consider as their own,”[xviii] the appearance of illustrations of the Shahnama was “either a way to ‘Iranize’ the Mongol rulers of Iran or to make them appear as supporters of the Iranian past through images accessible to all, literate or not.”[xix] After all, Iskandar was a conqueror of Iran, just like the Mongols, and hence became their own model in the Shahnama, as “the conqueror who became a defender of Iran's past.”[xx] The prominence of illustrations in The Great Mongol Shahnama, with such a focus on Iskandar, was almost certainly a way for the Mongols to create a correspondence between themselves and Iskandar: both conquerors of Iran. Illustrating the Shahnama — and specifically using Iskandar — was a way for these new Mongol rulers to show their support of Iran and its past, despite their recent conquest of it. It is also interesting to note that, in the instance of every new ruler after the conquest of Islam in Iran, one of the first things commissioned was a copy of the Shahnama.[xxi] The Mongols, of course, were no exception to this, and their commissioning of The Great Mongol Shahnama was likely in their attempt to become a part of the historical legacy of Iran. By calling on the tradition of Iskandar, the Mongols could establish themselves with a sort of legitimacy that would help solidify their recent conquest.[xxii] These are just a few of the factors that help the viewer better understand the illustrated manuscript, and hence the painting depicting the scene of mourning over Iskandar, as a part of the greater community at the time.

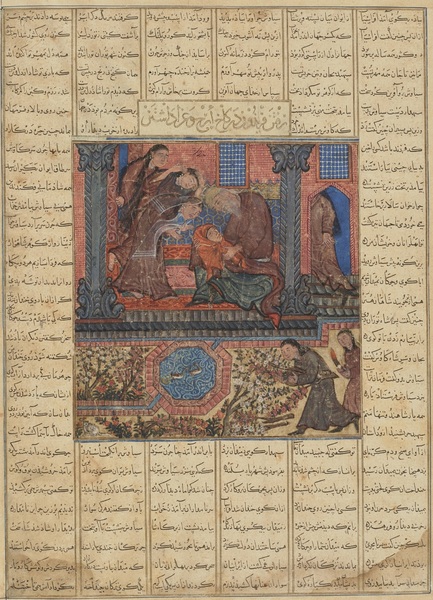

The whereabouts of The Great Mongol Shahnama, and hence the folio painting that depicts the scene of mourning over Iskandar, are unknown until the nineteenth century, when it appeared in the capital of Iran, Tehran.[xxiii] A little while later, the manuscript was taken out from Iran to Paris, where Georges Demotte, an art dealer, acquired it around the year 1910.[xxiv] Demotte could not resell the manuscript as a whole, and as a result, decided to “break it up into folios, split the folios with both recto and verso paintings into two separate sheets, and then paste the loosened pages on irrelevant text folios so that he could sell individual folios.”[xxv] It is important to note, however, that the mourning of Iskandar folio was not altered by Demotte.[xxvi] Many others were altered however, which make it “extremely difficult to reconstruct the original state of the manuscript.”[xxvii] Despite these alterations, scholarly research has indicated that the original manuscript likely had about three hundred folios, with a frequency of illustrations higher than any other folio. This is why the prominence of illustrations in The Great Mongol Shahnama is considered by some, in the entire history of Iranian art, as “probably only second to the Safavid Shahnama manuscript for Shah Tahmasp (r. 1524–76) which originally contained 258 paintings.”[xxviii] A painting from this illustrated manuscript is pictured on the right.

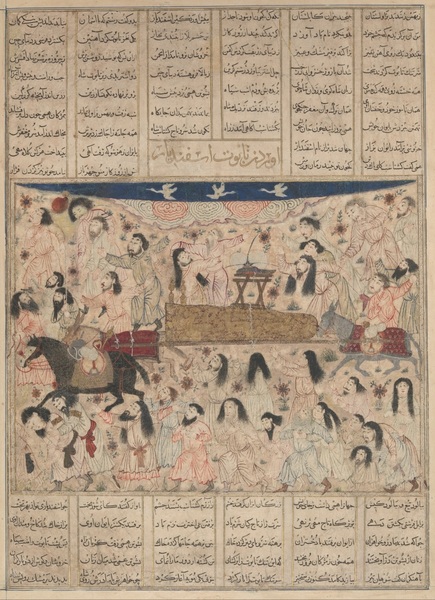

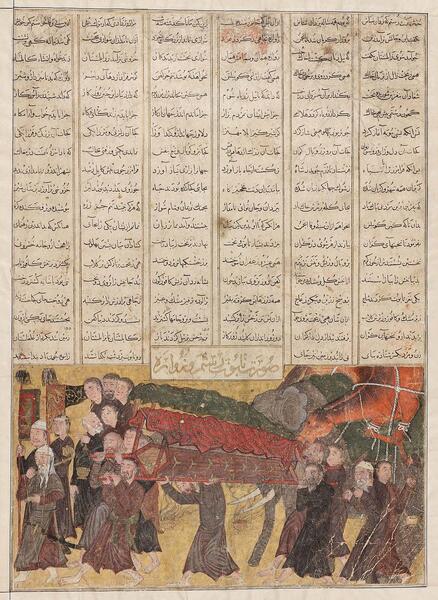

Paintings in The Great Mongol Shahnama that depict scenes of mourning, however, are among its most famous illustrations. In addition to the folio painting that depicts the scene of mourning over Iskandar, there are four others (five total) that also show scenes of mourning.[xxix] All four are pictured below: two on the left and two on the right. These paintings, in their own unique way, all show how the Islamic community experienced death at the time. The folio painting depicting the mourning over Iskandar, however, is widely regarded as the most famous of these illustrated scenes.

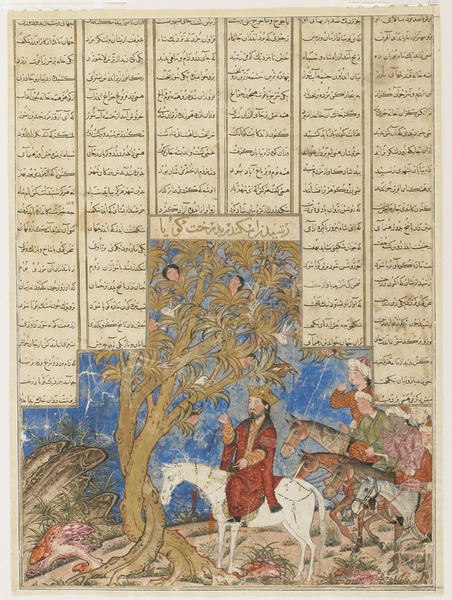

The folio painting depicting the mourning over Iskandar is from the section in the Shahnama that corresponds with historical kings: in this case, Macedonian king Alexander the Great. There are 12 different illustrations from the Book of Iskandar in The Great Mongol Shahnama that have survived; Iskandar at the talking tree, pictured right, is another well-known illustration from the manuscript, but the painting that depicts the scene of mourning over the death of Iskandar is still the most famous illustrated manuscript involving him. In fact, this painting is among the most famous in the entirety of The Great Mongol Shahnama, largely in part due to the intensity of the emotional representation of the wailing figures and the intense grief prominent throughout: all of which emphasize the impact that Iskandar’s death had on the community.

There are many specific details present throughout the painting that highlight this impact. Most prominently, the viewer observes a woman (in blue) at the center of the painting, assumed to be the mother of Iskandar, flinging herself onto the coffin with outstretched hands; her intense grief is fully expressed by the way she clings to it. Also prominently displayed in the painting is a man (center background), kneeling over Iskandar’s coffin while he weeps into a handkerchief. This is presumed to be Aristotle, Iskandar’s childhood teacher: visibly distressed because of his close relationship with Iskandar. In the Shahnama, Iskandar follows Aristotle's counsel in all things, and in general, Aristotle is Iskandar’s teacher and minister, even writing a book of government for him.[xxx] Both Iskandar’s mother and Aristotle can be seen in a close-up of the painting, shown left. While the grief of these two is certainly most prominent in the painting, they were far from the only ones impacted by Iskandar’s death.

Even though Iskandar had invaded Iran during his life, it is clear in this painting that he is truly being mourned, showing that he had been fully embraced by the community who mourns his death.[xxxi] This is evident through the intense emotion displayed by the masses that surround his coffin, and by the unidentified chorus of women in the front who tear their hair in grief.[xxxii] Additionally, there are various details displayed throughout the painting that highlight the importance of Iskandar to the community. For example, the interior setting itself is perhaps a way to highlight this importance. In the text of the Shahnama, when Iskandar dies, his coffin was put on display in an open landscape.[xxxiii] As seen in the painting, however, the setting has been transformed into an elaborate architectural complex with lamps and curtains, and numerous lavish decorations everywhere.[xxxiv] This interior has various luxury objects, such as monumental candles, a great lamp, luxury carpets, textiles, and tiles: a visual testimony of the types of luxury objects that existed at the time, all of which underscore the importance of Alexander to the community that mourns him.[xxxv] Additionally, the artist confining Iskandar’s coffin into an interior space better depicts the intensity of the surrounding emotions. As previously mentioned,[xxxvi] this may have simply been a product of incomplete information in the text of the folio, but regardless, the interior setting more intensely displays how the community experienced Iskandar’s death. In a more confined interior space, the intense grief circulates around the coffin; the more notable figures such as Iskandar’s mother and Aristotle are much more prominent in this setting, in addition to the onlookers displaying great agony. All of these elements better show the great impact that Iskandar’s death had on the community at the time.

The folio painting that depicts the scene of mourning over the death of Iskandar has a unique backstory, and while there are a variety of interpretations regarding the motivation behind certain elements, one thing is clear: the painting features prominent grief within a luxury setting that clearly displays the intense impact that Iskandar’s death had on the community at the time.

[i] Barry Wood, Invented History, Fabricated Power: The Narrative Shaping of Civilization and Culture (London: Anthem Press, 2020), 233.

[ii] Massumeh Farhad and Steven Zucker, "Alexander, the Mongols, and the Great Epic of Iran," in Smarthistory, December 10, 2019, video, 6:07, https://smarthistory.org/shahnama-bier-alexander/.

[iii] Masuya Tomoko, “Visualization of Texts Scenes of Mourning in the Great Mongol Shahnama,” Orient 52 (2017): 5.

[iv] Tomoko, “Visualization of Texts Scenes of Mourning in the Great Mongol Shahnama,” 5.

[v] Tomoko, “Visualization of Texts Scenes of Mourning in the Great Mongol Shahnama,” 5.

[vi] Tomoko, “Visualization of Texts Scenes of Mourning in the Great Mongol Shahnama,” 5-6.

[vii] Tomoko, “Visualization of Texts Scenes of Mourning in the Great Mongol Shahnama,” 6.

[viii] Tomoko, “Visualization of Texts Scenes of Mourning in the Great Mongol Shahnama,” 13.

[ix] Abolqasem Firdawsi, Shahnameh: The Persian Book of Kings, trans. Dick Davis (New York, New York: Penguin Books, 2016), 680

[x] Tomoko, “Visualization of Texts Scenes of Mourning in the Great Mongol Shahnama,” 14.

[xi] Tomoko, “Visualization of Texts Scenes of Mourning in the Great Mongol Shahnama,” 14.

[xii] Sheila Blair, Text and Image in Medieval Persian Art (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2019), 134-35.

[xiii] Blair, Text and Image in Medieval Persian Art, 135.

[xiv] Oleg Grabar and Sheila Blair, Epic Images and Contemporary History: The Illustrations of the Great Mongol Shahnama (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1980), 33.

[xv] Grabar and Blair, Epic Images and Contemporary History: The Illustrations of the Great Mongol Shahnama, 33.

[xvi] Oleg Grabar, “Why Was the Shahnama Illustrated?” Iranian Studies 43, no. 1 (2010): 95.

[xvii] Grabar, “Why Was the Shahnama Illustrated?” 95.

[xviii] Grabar, “Why Was the Shahnama Illustrated?” 95.

[xix] Grabar, “Why Was the Shahnama Illustrated?” 95.

[xx] Grabar, “Why Was the Shahnama Illustrated?” 95.

[xxi] Farhad and Zucker, “Alexander, the Mongols, and the Great Epic of Iran.”

[xxii] Farhad and Zucker, “Alexander, the Mongols, and the Great Epic of Iran.”

[xxiii] Tomoko, “Visualization of Texts Scenes of Mourning in the Great Mongol Shahnama,” 6.

[xxiv] Tomoko, “Visualization of Texts Scenes of Mourning in the Great Mongol Shahnama,” 6.

[xxv] Tomoko, “Visualization of Texts Scenes of Mourning in the Great Mongol Shahnama,” 6.

[xxvi] Tomoko, “Visualization of Texts Scenes of Mourning in the Great Mongol Shahnama,” 12.

[xxvii] Tomoko, “Visualization of Texts Scenes of Mourning in the Great Mongol Shahnama,” 6.

[xxviii] Tomoko, “Visualization of Texts Scenes of Mourning in the Great Mongol Shahnama,” 6.

[xxix] Grabar and Blair, Epic Images and Contemporary History: The Illustrations of the Great Mongol Shahnama, 18.

[xxx] Minoo S. Southgate, “Portrait of Alexander in Persian Alexander-Romances of the Islamic Era,” Journal of the American Oriental Society 97, no. 3 (1977): 282.

[xxxi] Farhad and Zucker, “Alexander, the Mongols, and the Great Epic of Iran.”

[xxxii] Grabar and Blair, Epic Images and Contemporary History: The Illustrations of the Great Mongol Shahnama, 134.

[xxxiii] Firdawsi, Shahnameh: The Persian Book of Kings, 680

[xxxiv] Grabar and Blair, Epic Images and Contemporary History: The Illustrations of the Great Mongol Shahnama, 134.

[xxxv] Farhad and Zucker, “Alexander, the Mongols, and the Great Epic of Iran.”

[xxxvi] Tomoko, “Visualization of Texts Scenes of Mourning in the Great Mongol Shahnama,” 14.

Bibliography

Sheila Blair, Text and Image in Medieval Persian Art. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2019, 112–71. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.3366/j.ctvxcrp75.9.

Grabar, Oleg, and Sheila Blair. Epic Images and Contemporary History: The Illustrations of the Great Mongol Shahnama. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1980.

Grabar, Oleg. “Why Was the Shahnama Illustrated?” Iranian Studies 43, no. 1 (2010): 91–96. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40646812.

Firdawsi, Abolqasem. Shahnameh: The Persian Book of Kings. Translated by Dick Davis. New York, New York: Penguin Books, 2016.

Farhad, Massumeh, and Steven Zucker. “Alexander, the Mongols, and the Great Epic of Iran.” December 10, 2019 in Smarthistory. Video, 6:07. https://smarthistory.org/shahnama-bier-alexander/.

Southgate, Minoo S. “Portrait of Alexander in Persian Alexander-Romances of the Islamic Era.” Journal of the American Oriental Society 97, no. 3 (1977): 278–84. https://doi.org/10.2307/600734.

Masuya, Tomoko. “Visualization of Texts Scenes of Mourning in the Great Mongol Shahnama.” Orient 52 (2017): 5–20. https://doi.org/10.5356/orient.52.5.

Barry Wood, Invented History, Fabricated Power: The Narrative Shaping of Civilization and Culture. London: Anthem Press, 2020, 233–44. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvz937bh.27.