Al-Ma'thur Catalogue Entry

What comes to mind when one thinks of a sword? Is it war, violence, power, artistic prowess, or opulence? Throughout history, these abstract themes seem to have become intertwined with concrete objects like swords, daggers, and sabers. ‘Sayf,’ or the Arabic word for ‘sword,’ has at least one thousand synonyms—needless to say, the sword is a frequently talked about item in the Arab tradition. Among the most cherished of these blades are swords associated with or belonging to the Prophet Muhammad.[1] Islamic empires of the past not only deemed it necessary to establish dominance through military conquest, but they also wanted to do it in style! For this reason, the extravagant nature of armor, weaponry, and metalwork progressed with the times and evolved as artisanal techniques improved and one empire overtook another. Even a weapon dating all the way back to the Prophet Muhammad underwent a sort of reincarnation throughout different conquests of the Muslim-dominated lands. While it is true that all that glitters definitely does not qualify as gold, the connotations of gold weaponry and armor are clear: those who possessed a weapon of such material were meant to be revered, admired, and seen as a cut above all the rest.

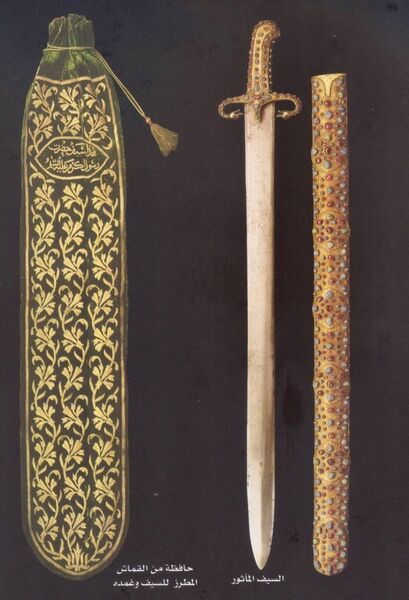

The Prophet Muhammad wielded nine swords throughout his life, one of them being Al-Ma'thur. Also known as Ma’thur al-Fijar, the sword measures ninety-five centimeters long in total, with the handle making up fourteen of those centimeters and the steel blade making up the other eighty-one centimeters. The handle is four centimeters wide and is currently covered in gold and adorned with precious rubies and emeralds and semi-precious turquoise. As the hilt curves outward, it reveals two snakes with gaping mouths, bared fangs, and blood-red ruby eyes. Along with the handle, the sword’s scabbard is also currently made of gold and encrusted with ruby, emerald, and turquoise stones. Further, the sword now has a fabric sheath-- it is a beautiful emerald-green color, complete with gold vegetal embroidery.[2] The animalistic and vegetal motifs from the newer and more elaborate parts of the weapon are characteristically Ottoman and reflect the trends of this time period. The Ottomans were known for their floral patterns, but the serpents on the hilt can be attributed to Timurid influence on Ottoman metalwork.[3]

Al Ma’thur was commissioned in Mecca by the Prophet Muhammad’s father, Abdullah ibn Abd al-Muttalib, toward the late sixth century or early seventh century. The sword’s creation was ordered prior to the Prophet’s first revelations, but Muhammad kept it with him when he migrated from Mecca to Medina.[4] At this point in Meccan history, the land was not rich in the resources necessary for sword crafting, so a bit of international commerce was necessary. Meccan merchants imported materials such as ’udm,’ or leather that would have served as the overlay of the Prophet‘s sword, from places like Yemen or Persia.[5] While the weapon is indeed decorated very extravagantly in the present, the handle was originally made from wood and covered with leather. Prior to the spread of Islam and the inevitable increase in commerce that went along with the emergence of a new religion, Arabian metalworkers kept their craft simple. For centuries, casting, followed by beating sheet metal and rotating it on a lathe, was the preferred method for metal craftsmen. As for decorative metalwork, piercing, chasing, embossing, engraving, and inlay were the favored manners of getting the job done.[6]

Muhammad eventually passed Al-Ma’thur down to Ali ibn Abi Talib. Ali was the cousin and son-in-law of the Prophet, and he was also one of Muhammad’s first four successors. These first four caliphs were known as the “rightly guided” (Rashidun), but Ali had a special place in the Prophet’s heart—he was known to be Muhammad’s inheritor and closest friend. Ali also went on to wed Fatima, the Prophet’s daughter, and fought with and defended Muhammad at the battle of Uhud. It was only after this battle that Al-Ma'thur, along with other battle equipment, came under Ali ibn Abi Talib’s possession.[7] After the death of Ali in 661, the Umayyad dynasty took over the caliphate and was granted jurisdiction over the Prophet’s belongings, which were housed in the Kaaba. The possession of Muhammad’s relics became symbols of spiritual and political legitimacy, and this remained true as one group overthrew another. Throughout the developmental days of the version of Al-Ma‘thur that museumgoers see today, four empires enjoyed a reign of power and influence over its condition and whereabouts: the Ottomans, the Mamluks, the Abbasids, and the Umayyads. The Ottomans, though, whose sultans were great patrons of the arts and did extravagance better than anyone else, were the most recent empire to come into possession of the Prophet’s belongings.[8] Due to the fact that there was quite a bit of gift-giving and interchange between Mamluk authorities, it is difficult to pinpoint the exact whereabouts of the Prophet’s relics during this period. There also tends to be an overlap between the Mamluk and Ottoman metalwork trends, simply because the two empire’s reigns occurred one after the other. Upon his establishment in power, the Ottoman caliph Selim I also took Muhammad’s cloak, bow, and swords, also previously kept in the Kaaba. Selim took tremendous pride in the fact that he now owned these relics, and the Ottomans restored ancient objects to their former glory. In the case of Al-Ma’thur, the sword was modernized and repurposed for the grandiose needs of the Ottomans.

While Al-Ma'thur was most likely used by Muhammad for defense during his migration and in battle, the weapon took on a very new and different role in later centuries. The Ottomans were known to conduct lengthy and extravagant coronation ceremonies for their newly legitimized sultans. A crucial part of these ceremonies was the girding of the new sultan. He was allowed to choose a sword from the Topkapi Palace treasury—this reservoir included the swords of the prophet, some of his companions, or various caliphs from over the years. The sultan would be girded and given a sash and his sword of choice, and this was usually followed by a procession and prayer.[9]

The fact that the Ottomans chose to refurbish Al-Ma'thur in gold speaks volumes about their feelings toward the precious metal and how it relates to the Prophet Muhammad. When he is physically represented in art, the most revered man in Islam is frequently draped in gold cloth or has his head encircled by a golden halo. This is traditionally accepted as a representation of his enlightened mind and primordial, heavenly essence. This likens the use of gold to celestial paradise, and therefore, perfection. Furthermore, the use of gold in art and metalwork was reserved for those most high, as gold was a rare commodity. Just like Al Ma'thur, Muhammad's beard box, mantle, and additional swords were also lavishly ornamented in gold to also accentuate his extravagence. [10] However, as aforementioned, an empire such as the Ottomans spared no expense in regard to their nobles and ceremonies.[11] The opulent refurbishment of relics like Al-Ma'thur is, in essence, the culmination of centuries-old passion for extravagance and legitimacy.

[1] Elgood, Robert, and Abdel Rahman Zaky. “Medieval Arab Arms.” Essay. In Islamic Arms and Armour, 203–. London: Scholar P., 1979.

[2] Aydın, Hilmi, Uğurluel Talha, and Doğru Ahmet. “The Sacred Swords.” Chapter. In The Sacred Trusts: Pavilion of the Sacred Relics, Topkapı Palace Museum, Istanbul, 267–69. Light, 2004.

[3] Behrens-Abouseif, Doris. Essay. In Metalwork from the Arab World and the Mediterranean, 271–80. Thames & Hudson, 2022.

[4] “Al-Ma'thur.” United States Naval Academy. Accessed April 30, 2023. https://www.usna.edu/Users/humss/bwheeler/swords/mathur.html.

[5] Serjeant, R. B. Review of Meccan Trade and the Rise of Islam: Misconceptions and Flawed Polemics, by Patricia Crone. Journal of the American Oriental Society 110, no. 3 (1990): 472–86. https://doi.org/10.2307/603188.

[6] Elgood, Robert, and Abdel Rahman Zaky. “Medieval Arab Arms.” Essay. In Islamic Arms and Armour, 203–. London: Scholar P., 1979.

[7] Afsaruddin, A. and Nasr, Seyyed Hossein. "ʿAlī." Encyclopedia Britannica, January 1, 2023. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Ali-Muslim-caliph.

[8] “Chronology.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, February 15th, 2020. https://www.metmuseum.org/learn/educators/curriculum-resources/art-of-the-islamic-world/introduction/chronology

[9] Brookes, Douglas S. “Of Swords and Tombs: Symbolism in the Ottoman Accession Ritual.” Turkish Studies Association Bulletin 17, no. 2 (1993): 1–22. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43384431.

[10] Gruber, Christiane. “Between Logos (Kalima) and Light (NŪR): Representations of the Prophet Muhammad in Islamic Painting.” Muqarnas, Volume 26, 2009, 229–62. https://doi.org/10.1163/ej.9789004175891.i-386.66. Alexander, David. “Swords from Ottoman and Mamluk Treasuries.” Artibus Asiae 66, no. 2 (2006): 13–34. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25261853.

[11] Brookes, Douglas S. “Of Swords and Tombs: Symbolism in the Ottoman Accession Ritual.” Turkish Studies Association Bulletin 17, no. 2 (1993): 1–22. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43384431.

Works Cited

Afsaruddin, A. and Nasr, Seyyed Hossein. "ʿAlī." Encyclopedia Britannica, January 1, 2023. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Ali-Muslim-caliph.

“Al-Ma'thur.” United States Naval Academy. Accessed April 30, 2023. https://www.usna.edu/Users/humss/bwheeler/swords/mathur.html.

Aydın, Hilmi, Uğurluel Talha, and Doğru Ahmet. “The Sacred Swords.” Chapter. In The Sacred Trusts: Pavilion of the Sacred Relics, Topkapı Palace Museum, Istanbul, 267–69. Light, 2004.

Behrens-Abouseif, Doris. Essay. In Metalwork from the Arab World and the Mediterranean, 271–80. Thames & Hudson, 2022.

Brookes, Douglas S. “Of Swords and Tombs: Symbolism in the Ottoman Accession Ritual.” Turkish Studies Association Bulletin 17, no. 2 (1993): 1–22. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43384431.

“Chronology.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, February 15th, 2020. https://www.metmuseum.org/learn/educators/curriculum-resources/art-of-the-islamic-world/introduction/chronology

Elgood, Robert, and Abdel Rahman Zaky. “Medieval Arab Arms.” Essay. In Islamic Arms and Armour, 203–. London: Scholar P., 1979.

Gruber, Christiane. “Between Logos (Kalima) and Light (NŪR): Representations of the Prophet Muhammad in Islamic Painting.” Muqarnas, Volume 26, 2009, 229–62. https://doi.org/10.1163/ej.9789004175891.i-386.66. Alexander, David. “Swords from Ottoman and Mamluk Treasuries.” Artibus Asiae 66, no. 2 (2006): 13–34. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25261853.