Tughra of Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent Catalogue Entry

What is the Tughra of Suleiman the Magnificent?

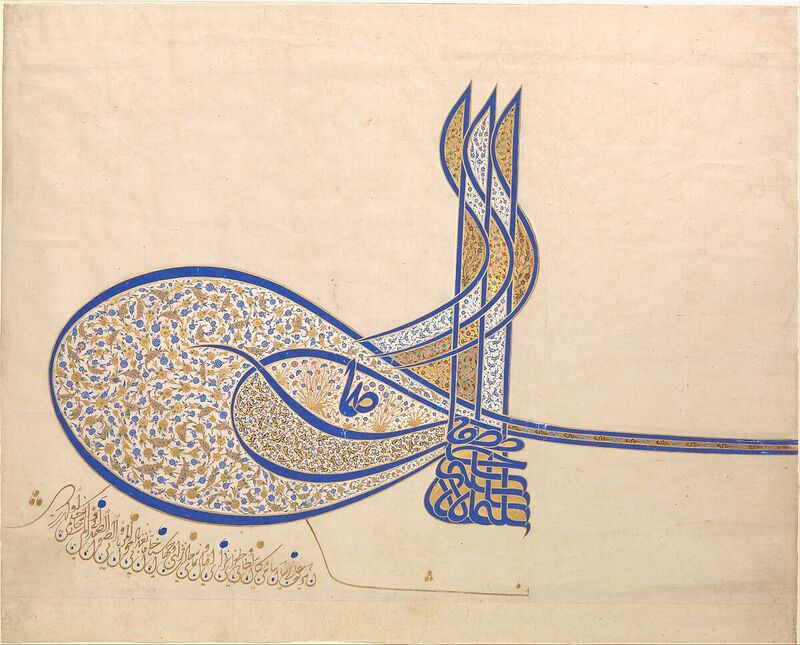

Tughra is a word of Turkish origin,[i] and generally refers to the official signature of a sultan. The Tughra of Suleiman the Magnificent is therefore the official signature of Ottoman Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent. It often appears at the top of official documents and is a symbol of Ottoman imperial power.[ii] When translated, the signature reads “Suleymān Shah son of Selīm Shah Khān, always victorious.”[iii] Tughra was typically accompanied by an additional formula which reads “This is the noble, exalted, brilliant sign-manual, the world illuminating and adoring cipher of the Khakan (may it be made efficient by the aid of the Lord and the protection of the Eternal). His order is that.”[iv] Both the signature and the accompanying script were designed to indicate the Sultan’s support for the mandate it preceded. This specific Tughra is in the Turkish calligraphic script Jari.[v] It “consists of vertical strokes and elongated lines, contrasting with wide intersecting ovals” and is written on paper with blue watercolor that is outlined in gold. The elegant decoration in the interior of the letters consists of “spiraling scrolls of stems, blossoms, plants, and cloud bands.”[vi] It is 52.1cm high and 64.5cm across. This Tughra was on the top of a Firman, a royal mandate or decree.[vii]

When was it made?

Scholars have been unable to precisely date any of the Tughras created during Sulieman the Magnificent’s reign, whose reign stretched from 1520-1566 C.E.[viii] However, this Tughra is believed to be from later in Sulieman the Magnificent’s reign, due to their bichrome palette and naturalistic flowers, which were popular artistic features of Suleiman’s later rule.[ix] It is estimated to have been created in 1555-1560 C.E.

Who made this, and how was it produced?

Suleiman the Magnificent was a major patron of art within the Ottoman Empire, and his personal involvement was the “driving force” behind the Golden Age of Ottoman Art.[x] Suleiman the Magnificent supported a linguistically and ethnically diverse group of court artists. These artists used their wealth of cultural experiences to incorporate a wide array of artistic styles, designs, and techniques into Ottoman royal art. Under Sulieman the Magnificent's patronage, these artists developed a distinct Ottoman style of art, characterized by “masterful floral and vegetal forms”. The unique Ottoman style was incorporated into the design of Tughras under Sulieman the Magnificent’s rule, giving them a distinct appearance from the Tughras of previous Sultans.

The Tughras of Sulieman the Magnificent were created by the artisans of the Sultan’s court. However, only a select number of special officers known as the Nishānji or Tughrakes were allowed to create the special calligraphic signatures. These officers were high ranking court officials, akin to a government Chancellor in the West.[xi] To execute mandates, the Nishānji had the special authority to add the Tughra emblem at the top of all official documents. Nishānji worked with designated illuminators in the Imperial Chancery, known as Divan, located in the Topkapi Palace in the Ottoman capital of Constantinople. Together, these skilled artists rendered documents “aesthetically superb, in order to reflect the power and magnificence of the ruling Sultan.”[xii] This specific Tughra was likely created in the Divan as well, as it has been identified as originating from Constantinople, and the Divan was the major source of Tughras during Sulieman the Magnificent’s rule.[xiii]

Why was it made, and how was it used?

Tughras were made and used to “visually convey the Sultan’s identity and showcase the talents of his Court artists.”[xiv] The vibrant colors and elaborate details expressed both the wealth and power of the Sultan and served as proof of the quality of work of his chosen artisans. The goal of any document bearing a Tughra was to communicate a message bearing authority, and to indicate the Sultan’s support for the message of that document.[xv] Furthermore, the calligraphy was exceedingly elaborate to prevent forgeries.[xvi] This ensured that Suleiman the Magnificent's signature could not be copied for illicit purposes and used against his wishes. As such, the detailed nature of the Tughra ensured the sanctity of the Sultan’s authority. Tughras were primarily used on imperial edicts, coins, monuments, and royal documents, although they were also sometimes affixed to less important documents.[xvii] This Tughra was created at the top of a royal mandate, although scholars are unsure about the content of the mandate itself.

How does the Tughra of Suleiman the Magnificent relate to legitimization?

The Tughra of Suleiman the Magnificent was used to legitimize his rule and enforce his authority across the Ottoman Empire. Besides the epithet “the Magnificent”, Suleiman was also known by the name “the Lawgiver”. This epithet stems from his extensive legal reforms, which included an overhaul of the formerly piecemeal Ottoman legal system, the creation of income-based taxes, and a reopening of trade with the Safavid Empire.[xviii] In order to enforce these reforms, Suleiman the Magnificent relied heavily on the extravagance of his Tughras to impress Ottoman citizens with his authority and power. The Tughra would mark documents as official and ensure its veracity as an edict coming from Suleiman the Magnificent. In creating a uniform, verifiable method of denoting imperially backed documents, Suleiman the Magnificent was able to extend his authority across the Ottoman Empire, without the risks that came from delegating the legal system to lower authorities.[xix] As a result, the Tughras became markers of Suleiman’s legitimate rule, minimizing illicit forgeries and providing visual symbols of the Sultan’s authority.

The Tughras also apply the legitimizing factors to the text of whichever edict of document the Tughra is on top of, as it directly attributes the text of the document to the words of Suleiman the Magnificent. The widely recognized Tughra was “symptomatic of a particularly efficient bureaucratic and institutional structure of regulation and law.”[xx] The efficiency and respect the Tughras demanded was further extended through their usage on Ottoman coins.[xxi] The reminder of the Sultan’s authority on the coins implied to the common people who used them that Suleiman the Magnificent was the source of their, and the Ottoman Empire’s wealth, fostering legitimacy for Suleiman the Magnificent. The usage of the Tughra fostered the sense that all laws and wealth stemmed from the authority of Suleiman the Magnificent, inspiring support and creating legitimacy for his rule.

The actual text of the Tughras also served to legitimize Suleiman the Magnificent’s reign. The Tughras denoted Suleiman’s imperial birthright and invoked the power of God in support of his authority.[xxii] Given the importance of Islam within the Ottoman Empire and the respect given the Sultan’s lineage, specifically denoting these factors within the Tughra imbues the same authority into the words of Suleiman the Magnificent. The extravagant design of the Tughras, including this Tughra, always incorporates three upward strokes known as the seré. The shape of the monogram “had to conform as far as possible to the reigning sultan’s predecessors”. The development of the Ottoman Tughra, and the seré, traces back to Osman, the founder of the Ottoman dynasty.[xxiii] As a result, the incorporation of the seré in the design of the Tughra of Suleiman the Magnificent directly connects him to previous sultans and situates his authority with the historical authority of previous Ottoman rulers. Every Tughra designates not just Suleiman the Magnificent's power, but also the power and legitimacy of the Ottoman sultanate.

How does the Tughra of Suleiman the Magnificent relate to extravagance?

The features of the Tughra of Suleiman the Magnificent demonstrate the extravagance within the Ottoman sultanate. The bold blue and gold coloration carried important symbolic values during Suleiman the Magnificent’s time. Throughout the 16th and 17th centuries, blue signified “heaven, heavenly love, fidelity, truth, and holiness itself”[xxiv] within Islamic culture. For example, the Sultan Ahmed Mosque or the “Blue Mosque” was renowned for its blue coloration and sought to express extravagance via its size and splendor, being one of the few mosques with six minarets. The usage of bright blue watercolor in this Tughra connects to the symbolic meaning of the color and associate holiness and truth with the words and authority of Suleiman the Magnificent. The extravagant usage of gold within the Tughra also denotes the wealth and power of the Sultan. The color choices used within this Tughra rely upon historical symbols and the connection to other extravagant pieces of art and architecture.

Another aspect of extravagance within the Tughra was in its extensive detail. Only highly skilled artisans and calligraphers had the skill to create the fine details to the extent, number, and size demanded by the Tughra.[xxv] The usage of such details for official documents impressed viewers with the knowledge that the sultanate had the wealth and appeal to retain such skilled artisans. The cloud bands within the Tughra rely on the artistic styles of foreign empires, primarily drawing upon Persian and Chinese influences.[xxvi] This demonstrated the interconnectivity of the sultanate with other authoritative powers. At the same time, the incorporation of the cloud bands into a distinctly Ottoman artistic tradition also hinted at Ottoman artistic greatness, as artisans could use foreign artistic features for the Sultan’s distinct purposes. The Tughra of Suleiman the Magnificent featured extravagant details, whose very presence implied the wealth and capability of the Ottoman sultanate.

[i] Annemarie Schimmel and Barbar Rivolta, “Islamic Calligraphy,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 50, no. 1 (1992): 1+3-56.

[ii] Maryam D. Ekhtiar, and Claire Moore, Art of the Islamic World: A Resource for Educators, (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2012), 128-129.

[iii] Ralph Pinder-Wilson, “Tughras of Suleyman the Magnificent,” British Museum Quarterly 23, no. 1 (1960): 23. https://doi-org.flagship.luc.edu/10.2307/4422658.

[iv] Hannah E. McAllister, “Tughras of Sulaiman the Magnificent,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 34, no. 11 (1939): 247-248. https://doi-org.flagship.luc.edu/10.2307/3256652.

[v] McAllister, 247.

[vi] Ekhtiar and Moore, 128.

[vii] Ekhtiar and Moore, 128.

[viii] Ekhtiar and Moore, 128.

[ix] Pinder-Wilson, 23.

[x] Ekhtiar and Moore, 128.

[xi] McAllister, 247.

[xii] Maryam D. Ekhtiar, How to Read Islamic Calligraphy, (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2018) 49.

[xiii] Ekhtiar and Moore, 128.

[xiv] Ekhtiar and Moore, 128.

[xv] Ekhtiar, 49.

[xvi] Ekhtiar and Moore, 128.

[xvii] McAllister, 247.

[xviii] Albert Howe Lybeyer, The Government of the Ottoman Empire in the Time of Suleiman the Magnificent, (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1913), 159.

[xix] Lybeyer, 161.

[xx]Sivamohan Valluhan, The Clamour of Nationalism: Race and Nation in Twenty-First Century Britain, (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2019), 13.

[xxi] McAllister, 247.

[xxii] Pinder-Wilson, 23.

[xxiii] Pinder-Wilson, 23.

[xxiv] Vivian Jacobs, and Wilhelmina Jacobs, "The Color Blue: Its Use as a Metaphor and Symbol." American Speech 33, No. 1 (1958): 26-49.

[xxv] Ekhtiar and Moore, 128.

[xxvi] Pinder-Wilson, 23.

Bibliography:

Ekhtiar, Maryam D. How to Read Islamic Calligraphy. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2018.

Ekhtiar, Maryam D., and Claire Moore. Art of the Islamic World: A Resource for Educators. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2012.

Jacobs, Vivian, and Wilhelmina Jacobs. "The color Blue: Its Use as a Metaphor and Symbol." American Speech 33, No. 1 (1958): 26-49. https://doi.org/10.2307/453461.

Lybeyer, Albert Howe. The Government of the Ottoman Empire in the Time of Suleiman the Magnificent. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1913. https://doi.org/10.4159/harvard.9780674337053.

McAllister, Hannah E. “Tughras of Sulaiman the Magnificent.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 34, no. 11 (1939): 247-248. https://doi-org.flagship.luc.edu/10.2307/3256652.

Pinder-Wilson, Ralph. “Tughras of Suleyman the Magnificent.” British Museum Quarterly 23, no. 1 (1960): 23-25. https://doi-org.flagship.luc.edu/10.2307/4422658.

Schimmel, Annemarie, and Barbar Rivolta. “Islamic Calligraphy.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 50, no. 1 (1992): 1+3-56.

Valluhan, Sivamohan. The Clamour of Nationalism: Race and Nation in Twenty-First Century Britain. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2019.