Shah Mosque Muqarnas: Architectural Legacy of the Absolute Truth

The Shah Mosque Muqarnas

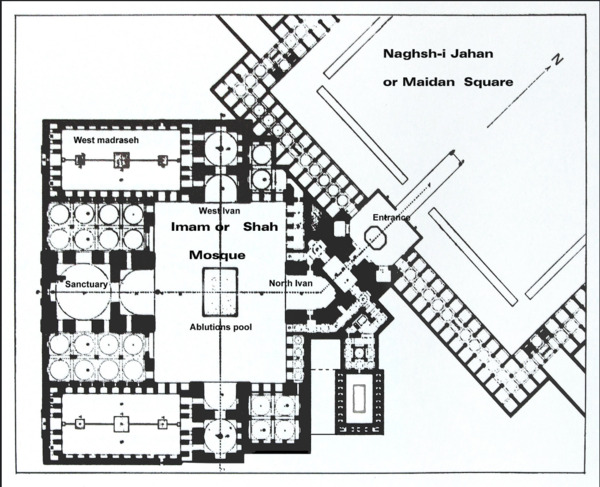

Constructed during the Safavid empire, the Shah Mosque in Isfahan, Iran has not only served as a place of worship for Muslims since the mid-seventeenth century (ca. 1631) but also as a representation of Islamic traditional architecture styles. Patronized by Safavid ruler Shah Abbas I, architect Ali Akbar Isfahani began construction in 1611 A.D, incorporating intricate tilework, domes, traditional Iranian turquoise, and the Islamic architectural form of muqarnas to create a four-iwan mosque.[1] Constructed using plaster and glazed tiles, the Islamic architectural feature muqarnas are suspended from the domes above, making them practically architecturally unsupported. Scholars have speculated numerous origins of muqarnas, citing examples of muqarnas in the tenth century in places such as Iran, North Africa and Iraq, yet the true origin is unclear.[2] Despite the indefinative origin, muqarnas are a known Islamic architectural tradition and incorporate Islamic ideology. The Shah Mosque muqarnas demonstrate the intersection of scale and extravagance in relation to the Islamic ideology of Absolute Truth. Interpretations of the Shah Mosque muqarnas consider how the spiritual context of Sufism, the fundamental muqarnas geometry, patterns of tilework and the incorporation of light on the muqarnas exemplify extravagance through transcending the material world and illustrating the Islamic themes of Absolute Truth and Allah’s Majesty.

[1] Mohammad Gharipour and Irvin Cemil Schick, Calligraphy and Architecture in the Muslim World (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press Ltd, 2013), 14.

[2] Yasser Tabaa, “The Muqarnas Dome: Its Origin and Meaning,” Brill 3, (1985): 61, https://www.jstor.org/stable/1523084.

Purpose and Contributors to the Shah Mosque

The Shah Mosque was constructed as a congregational mosque, signifying it was a space where citizens could attend religious services and pray. Unlike the Lutfallah Mosque, another mosque in Isfahan which operated as a private space, inscriptions on an iwan suggest Shah Abbas I patronized the Shah Mosque with the intention that it would be a gathering place for Muslims.[3] As a result, Shah Mosque was a massive economic undertaking for the Safavid empire and incorporated work from many architects, calligraphers, and tile cutters. Overall, the Shah Mosque was a grand architectural development requiring much craftsmanship and labor. A lower inscription on the portal of the Shah Mosque assigns Ali Akbar Isfahani as the lead architect and other endowments reference numerous calligraphers. Another inscription mentions Badi al-Zaman as a builder of the mosque, but his name is not included in the foundation inscription[4]. Not only was the Shah Mosque an expensive project but the inscriptions indicate a sizable portion of the human labor were educated-literate individuals. Although there were numerous builders and architects, there is no indication who constructed the muqarnas at Shah Mosque. However, the construction still took place under architect Ali Akbar Isfahan

Influential Islamic Ideology During the Safavid Empire

Settling in the region of modern-day Iran, the Safavid empire was closely linked to Islamic mysticism. Originally evolved from a Sufi order, the Safavid empire continued the practice of various Sufi orders such as the Nurbakhshi, Ni'matullah, Qadirl, and Zahabi.[5] Sufism, often known as Islamic mysticism, emphasizes strengthening one’s relationship with Allah by renouncing the material world and following the spiritual path leading to complete surrender to Allah. In addition, the Safavid empire saw many Sufi figures throughout the life of the empire, signifying the presence of active Sufi teaching in the community. Shaikh Baha' al-Din 'Amili, considered “the most powerful Shi'i figure in Persia” spread his writings on Islamic law and the Qur’an during the Reign of Shah Abbas I.[6] The influence of Sufi thought on the Safavid empire explains the prevalence of Islamic and metaphysical synthesis in Safavid art and architecture. As a result, Safavid architects incorporated symbolism reflecting man’s relationship with God through mosque architecture.[7] Sufism’s prevalence in the Safavid empire serves as a basis for analyzing the motifs within the Shah Mosque muqarnas. Furthermore, the influence of Sufi order proves symbolism of Absolute Truth is not a new interpretation of muqarnas.

[5] S. H. Nasr, “Spiritual Movements, Philosophy and the Theology in the Safavid Period,” in The Cambridge History of Iran, ed. Peter Jackson, Lawrence Lockhart (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986).

[6] Nasr, “Spiritual Movements,” 666.

[7] Amir Esmi and Hamidreza Saremi, “Mysticism and Its Impact on Safavid Dynasty Architecture (Mosque of Sheikh Lotfollah in Isfahan),” Maxwell Scientific Organization, (2014): 333-339.

The Geometry of the Shah Mosque Muqarnas

The Shah Mosque muqarnas was constructed by overlapping a combination of prismatic elements to create a kaleidoscope-like, vaulted structure.[8] The Topkapi scrolls provide deeper insight into how the formation of cells form star-like shapes. Plans from a Uzbek master builder demonstrate how stellate and interlocking geometric patterns form intersected arch-net vaults.[9] The manipulation of shapes allows each cell of the muqarnas to form a three-dimensional structure with intersected vaults to display underlying prismatic shapes. Although some muqarnas may fulfill a structural role, such as the muqarnas vaults of the main dome of the Cairene madrasa of the sultan Barquq, the Shah Mosque muqarnas are suspended from the iwans and serve no structural role. The lack of structural purpose indicates the Shah Mosque muqarnas has a deeper visual purpose.

Since the Safavid empire was strongly linked to Islamic mysticism, scholars suggest the architects used mathematics and architecture as tools used to illustrate theological concepts and divine themes.[10] This interpretation counteracts previous interpretations which said muqarnas operated purely as a visual spectacle for viewers.[11] Instead of acting as a decorative feature, the construction of the Shah Mosque muqarnas uses mathematics to intentionally infuse the meaning of Allah’s Majesty. Prior to the construction of the Shah Mosque, Muslim theologists grappled over the idea of the universe in relation to Allah. As Muslims view Allah as Absolute and Eternal, a traditional dome could not display the infinity of the universe in respect to Allah’s Oneness. Under Baghdad caliph Al-Qadir, mathematicians began arranging basic prismatic shapes in a complex manner with distinct units, developing the muqarnas to illustrate how Allah continuously interferes with the universe.[12] The defined layered tiers of facets and roofs in the Shah Mosque muqarnas highlight Allah’s majesty as the Creator. As seen in the muqarnas in Baghdad’s Shrine of Zumurrud Khatun, the Shah Mosque muqarnas incorporate the geometric-vaulting structure developed under Al-Qadir, displaying resemblance between the two. Although Grabar claims, the geometry of muqarnas are merely “a passage, at best a magnet”[13] for interpreters to assign religious and cultural meaning, the symmetry of duplicated cells suggests associations to Islamic spirituality and worship.[14]

[8] Vicenza Garofalo, “A Methodology for Studying Muqarnas: The Extant Examples in Palermo,” Brill 27, (2010): 357, https://www.jstor.org/stable/25769702.

[9] Gulru Necipoglu and Mohammad al-Asad, The Topkapi Scrolls (Santa Moncia: The Getty Center for the History of Art and the Humanities, 1995), 11.

[10] Tabaa, “The Muqarnas Dome,” 72.

[11] Oleg Grabar, The Mediation of Ornament (Oxford: Princeton University Press, 1992), 135, 151.

[12] Tabaa, “The Muqarnas Dome,” 69.

[13] Oleg Grabar, The Mediation, 151.

[14] Esmi and Saremi, “Mysticism and Its Impact,” 336.

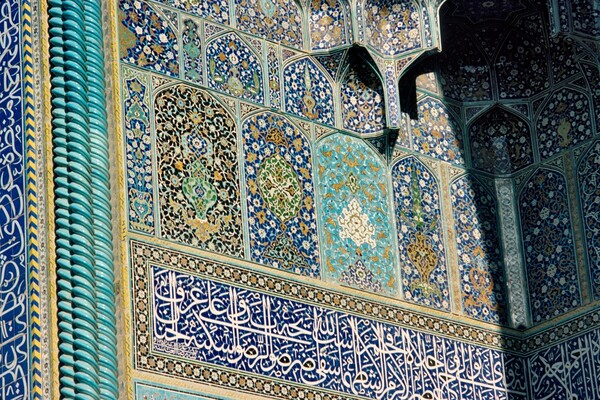

Tilework Decorating the Muqarnas at Shah Mosque

The muqarnas at Shah Mosque are decorated with glazed tiles illustrating intricate replicated-geometric patterns. Patterns are repeated; however, the Shah Mosque muqarnas uses a variety of patterns to display multiplicity. Even though numerous patterns are incorporated in the overall muqarnas at Shah Mosque, there is symmetry between the different designs, highlighting the uniformity of pattern.[15] Moreover, patterns utilize geometric shapes and plant motifs to resemble circles.[16] The circular patterns create continuity of movement and time, demonstrating how tilework on the Shah Mosque muqarnas supersedes earthly time and space. Symmetry and circle motifs were found in artwork from northern Iranian immigrant tribes to symbolize the Oneness and Completeness of Allah. Deep Iranian blues are contrasted with light turquoise and gold, creating depth and contrast of light.[17] The unity created through multiplicity and duplication of patterns resembles prominent Sufi thought during the Safavid empire. The intricate patterns which decorate the Shah Mosque muqarnas add yet another visual effect to invoke God’s Oneness and Absolute Truth. Whereas the glazed tile covering the Shah Mosque muqarnas utilize intricate geometric, slightly floral-like patterns to transcend the material world and convey Allah’s Oneness, the muqarnas at the Palatine Chapel incorporates painted vegetal, zoomorphic, and figural images.[18] The Shah Mosque muqarnas follows the common Islamic avoidance of figural imagery to describe God. Rather than displaying multiple stories like the decoration on the Palatine Chapel, the glazed tiles unite to describe Allah’s Oneness.

[15] Elham Parvizi, “The Manifestation of the Collective Unconscious in the Architecture of the Safavid Era in Iran (Case Study: Imam Mosque in Isfahan),” International Journal of Architecture and Urban Development 11, no. 2 (2021), 54, 10.30495/IJAUD.2021.17310.

[16] Mohammad Salehi Marzijarani, “Investigating the Visual Characteristics of the Designs of the Abbasi Great Mosque in Isfahan (Configurations, Compositions, and Motifs),” Journal of Positive School Psychology 6, no. 5 (2022): 9871-9872.

[17] J. Mahdi Nejad, A. Sadeghi Habib Abad, and E. Zarghami, “A Study on the Concepts and Themes of Color and Light in the Exquisite Islamic Architecture,” Journal of Fundamental and Applied Sciences, (2016), 1092, http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/jfas.v8i3.23.

[18] Agnello, Fabrizio, “The Painted Ceiling of the Nave of the Cappella Palatina in Palermo: An Essay on Its Geometric and Constructive Features," Muqarnas: An Annual on the Visual Culture of the Islamic World 27, (2010): 407-447.

The Incorporation of Light in the Muqarnas at Shah Mosque

The Shah Mosque muqarnas also incorporates natural light to exemplify the visual effect of the glazed tiles and complex geometry. As mentioned above, the Shah Mosque consists of four iwan structures, which the muqarnas suspend from. Each iwan faces a different cardinal direction; therefore, each muqarnas is caught by the sun at different times each day. The muqarnas located at the entrance of the mosque is oriented southwest, indicating the tiles glisten in the sun closer to sundown. It is crucial to recognize the orientation of mosques relates to the direction of the Kaaba, an important religious site in the Islamic tradition. There is another muqarnas facing directly west, one facing north and one facing south. Recent interpretations suggest a correlation between the use of light and darkness to reflect religious themes.[19] In an Islamic context, verses in the Qur’an associate light with a symbol of the presence of Allah; however, it is not certain the positioning of the Shah Mosque muqarnas intentionally invokes divine meaning. Another scholar assigned the incorporation of light in muqarnas to highlight an Ashari-Islamic theology which explains shape, color, and light as accidents by which are subject to continuous change in accordance with Allah.[20] Rather than light merely symbolizing the presence of Allah, Ashari thought suggests the seemingly unsupported muqarnas dome serves as proof for the existence of Allah and portrays Islamic Absolute Truth. Whether or not the Shah Mosque muqarnas were influenced by Ashari thought or Quranic verses pertaining to light is unclear. However, the position of the iwans in relation to the sun allow for light to continuously change throughout the day, accentuating the glazed tile work on each muqarnas at a different time.

[19] Nejad, Abad, and Zarghami, “Concepts and Themes of Color,” 1092-1093.

[20] Tabaa, “The Muqarnas Dome,” 69.

Extravagance and Scale Within the Muqarnas at Shah Mosque

Overall, the geometrical complexity of the facets and roofs, the intricate tilework, and the influence of light on the Shah Mosque muqarnas create an extravagant visual effect in and of itself. However, the true extravagance of scale in the Shah Mosque muqarnas is its ability to transcend the material world and display themes of Allah’s Oneness as the divine Creator and the Islamic Absolute Truth. Through the portrayal of divinity, the Shah Mosque muqarnas breaks the scale of size and represents the timeless authority of Allah.

Works Cited

Agnello, Fabrizio, “The Painted Ceiling of the Nave of the Cappella Palatina in Palermo: An Essay on Its Geometric and Constructive Features," Muqarnas: An Annual on the Visual Culture of the Islamic World 27 (2010): 407-447.

Babayan, Kathryn. “The Safavid Synthesis: From Qizilbash Islam to Imamite Shi’ism.” Iranian Studies 27, no. 1/4 (1994): 135–161.

Elham Parvizi, “The Manifestation of the Collective Unconscious in the Architecture of the Safavid Era in Iran (Case Study: Imam Mosque in Isfahan),” International Journal of Architecture and Urban Development 11 no. 2 (2021): 54. 10.30495/IJAUD.2021.17310.

Esmi, Amir and Hamidreza Saremi. “Mysticism and Its Impact on Safavid Dynasty Architecture (Mosque of Sheikh Lotfollah in Isfahan).” Maxwell Scientific Organization no. 6 (2014): 333-339.

Gharipour, Mohammad and Schick, Irvin Cemil , Calligraphy and Architecture in the Muslim World. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press Ltd, 2013.

Grabar, Oleg. A Mediation of Ornament. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1992.

Grevemeyer, Jan-Heeren. “The Timurid and Safavid Periods.” In The Cambridge History of Iran, edited by Peter Jackson and Laurence Lockhart. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986.

Gulru Necipoglu and Mohammad al-Asad. The Topkapi Scroll—Geometry and Ornament in Islamic Architecture. Santa Monica: The Getty Center for the History of Art and the Humanities, 1995.

Jackson, Peter, and Laurence Lockhart. The Cambridge History of Iran. Volume 6, The Timurid and Safavid Periods. Edited by Peter Jackson and Laurence Lockhart. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986.

Mahdi Nejad, J., A. Sadeghi Habib Abad, and E. Zarghami. “A Study on the Concepts and Themes of Color and Light in the Exquisite Islamic Architecture.” African Journals Online, no. 3 (September 2016): 1078-1096. http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/jfas.v8i3.23.

Mohammad Salehi Marzijarani, “Investigating the Visual Characteristics of the Designs of the Abbasi Great Mosque in Isfahan (Configurations, Compositions, and Motifs),” Journal of Positive School Psychology 6, no. 5 (2022): 9865-9880.

Nader, Ardalan. “Color in Safavid Architecture: The Poetic Diffusion of Light.” Iranian Studies 7, no. 1-2 (1974): 164–178.

Nasr, S. H., “Spiritual Movements, Philosophy and the Theology in the Safavid Period,” in The Cambridge History of Iran, edited by Peter Jackson, Lawrence Lockhart. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986.

Parvizi, Elham. “The Manifestation of the Collective Unconscious in the Architecture of the Safavid Era in Iran.” International Journal of Architecture and Urban Development, no. 2 (Spring 2021): 53-62.

Vicenza Garofalo, “A Methodology for Studying Muqarnas: The Extant Examples in Palermo,” Brill 27 (2010): 357-406.

Yasser Tabaa, “The Muqarnas Dome: Its Origin and Meaning,” Brill 3 (1985): 61-74.