Topkapi Palace Tile with Floral and Cloud-band Design - Catalogue Entry

This ornate tile once adorned a wall of the Ottoman Topkapi Palace in Istanbul. Produced by skilled artisans in the lavish kilns of Iznik in modern-day Turkey, this tile was located within the harem of Sultan Murad III and decorated a wall of the sultan’s private bedchamber. It is currently on view at The Met Fifth Avenue. [1]

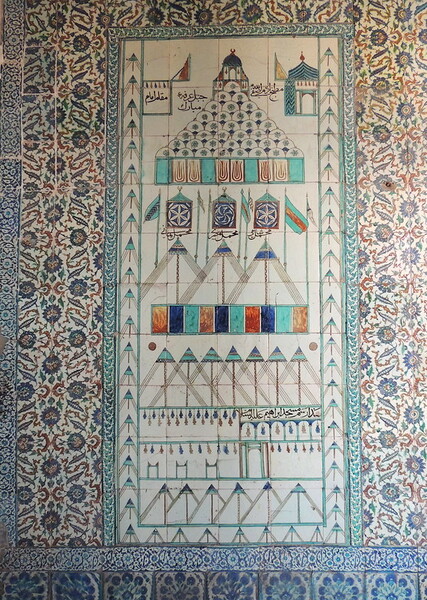

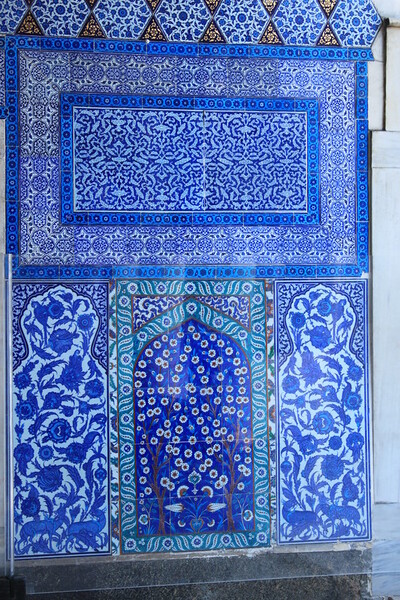

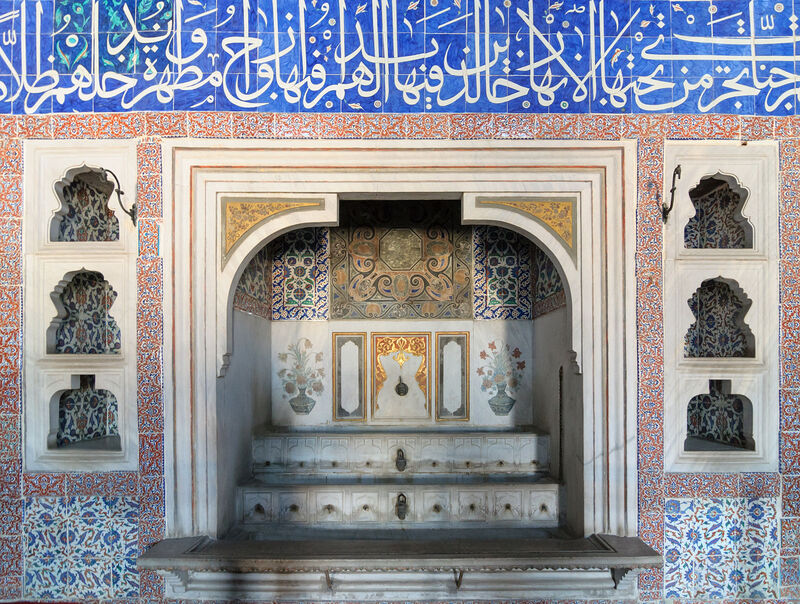

Crafted of clay-heavy stonepaste, [2] the polychrome pattern was designed at the imperial kilns of Iznik, along with most of the tile decorating Topkapi Palace. Comparably elaborate tile designs still adorn the walls of the sultan’s harem where this tile once lay. Construction of the harem as it still stands today was ordered under Sultan Murad III and directed by influential Ottoman architect Mimar Sinan. [3] The harem is one of the best preserved areas of Topkapi Palace and identical tiles remain in situ within Murad III’s private bedchamber today. [4]

The tile features ornamentation representing natural themes common in Islamic art. Animal figures were not rare in Ottoman tiles and ceramics and several notable examples are found within Topkapi Palace itself. [5] However, vegetal ornamentation was far more common and stylistically developed, taking center stage in Islamic art. The intricacy of this tile’s vegetal design demonstrates this development of complexity.

When placed alongside identical tiles, the four bisected floral palmettes become the focal points of a larger, more elaborate repeating design across the walls of the sultan’s bedchamber. These palmettes are largely a rich blue color, but contain flourishes of green and red. Their bold blue hue is enhanced by the subtle white background common in Ottoman tilework, [6] drawing attention towards the meticulously painted focal points. This trend in tile composition emerged largely in Ottoman art, as it was realized that attention could be better drawn to intricate design when it was paired with a simpler background. [7]

Long, serrated leaves complement the core palmettes. This particular leaf form originated in Ottoman vegetal decoration and was picked up by later Safavid and Mughal artisans. [8] These leaves serve to frame the more intricate palmettes within the larger tilework, their serrated edges directed towards the focal points. Although it may largely serve as a supportive artistic component, by observing this individual tile, it’s possible to closely observe the leaves’ red supporting elements. Red polychrome establishes the central veins of the leaves. Skillfully painted and glazed by Iznik artisans, the red elements have an elevated look and enhance the tile as a whole.

This tile, along with the thousands of similarly intricate tiles that decorate Topkapi Palace, were crafted and painted by hand in Iznik. [9] There is observable immaculate attention to detail in the red polychrome motifs alone. This level of craftsmanship in just one tile of thousands was likely an extravagant expense in both money and time for the sultan, architect Sinan and their artisans.

The leaves are enhanced by brightly colored, ribbon-like cloud bands. Like the central veins of the leaves, these clouds are painted in elevated red polychrome. This non-vegetal decoration is notable for its resemblance to common Chinese, rather than Islamic, ceramic motifs. Ottomans were notably fond of Chinese ceramic styles and often replicated its most famous characteristics. [10] Elites specifically were drawn by the imagery’s associations with ancient, heaven-mandated political status. The inclusion of clouds was likely a subtle, yet intentional allusion to the unquestionable power of Chinese emperors passed. [11] This imagery was so powerful among the Ottomans that by “using and elaborating on many Chinese motifs and themes, Ottoman artisans created a uniquely Ottoman style.” [12] This unique style is present within these cloud ribbons, as the painting style of Iznik artisans presents a distinctly Ottoman, rather than Chinese approach.

Besides extra-cultural imagery, Ottoman art itself had an inclination of depicting vegetal ornamentation as an allusion to the beauty of nature, and more broadly, the greatness of the world and heaven. [13] Illustration of a handful of nature’s most beautiful elements — flowers, leaves and clouds — remind of the glory of God’s creation. This connection between nature and God is underscored by the large quranic verses that span the sultan’s bedchamber, supported by these vegetal tiles. Tiling these themes across the sultan’s bedchamber implicates a strong connection between the ruler, nature and God’s power.

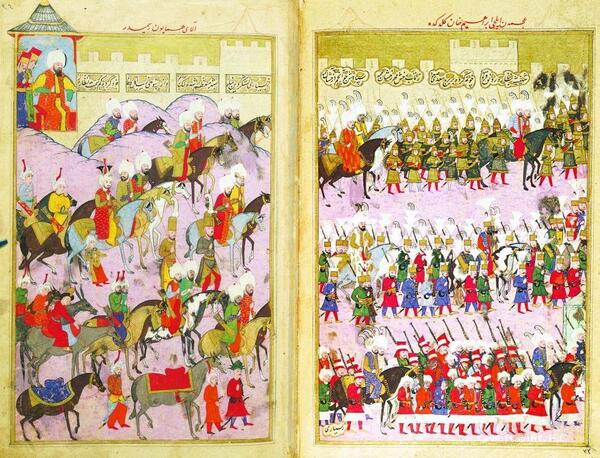

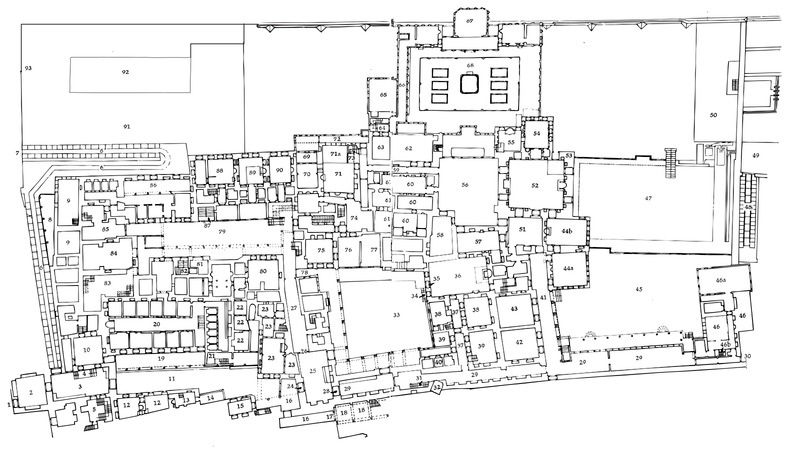

Topkapi Palace as a whole was intentionally designed to present power and hierarchy. From the first door off of the main road and on, the palace grows increasingly mysterious and restrictive. [14] The audiences allowed to pass subsequent gates grow more and more exclusive, with the harem being the most private of all. It housed the sultan and those closest to him. This included his concubines, children, eunuchs and the mistress of the harem, the Queen Mother. The sultan’s bedchamber may be the most exclusive chamber of all and this examined tile once adorned its walls. Completely cut off from the public — and even the most elite of visitors — guests could only use their imagination to picture harem life. [15] Keeping the sultan mysterious kept his image powerful in the eyes of palace and harem outsiders.

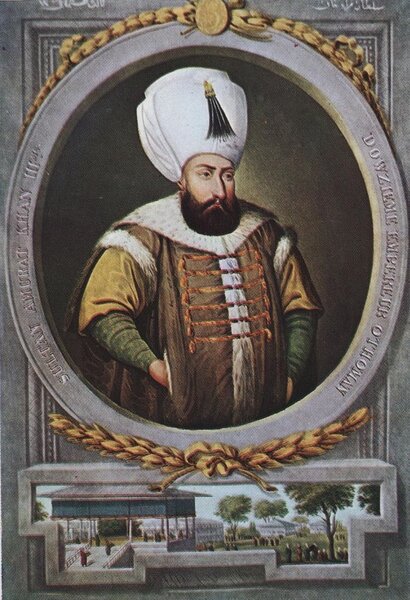

The harem as it still stands today was built more than a century after the initial palace construction under sultan Mehmed II, The Conqueror. [16] An omniscient figure across the palace, the sultan was meant to be unseen but felt in his presence through concealed observatories and hierarchy-based architecture. [17] Sultans tended to spend most of their time within the harem, however, and rarely left the harem except to attend various power-establishing holidays. [18] This was especially true for Murad III. The ruler notably stayed isolated in the harem for the final years of his reign, where he conducted both political and personal affairs. [19]

Besides commanding the construction of the harem, Murad III was an intense political player and the bold decoration of his harem supported his power. Just as elaborate Ottoman design in public spaces reinforced a ruler’s power over his subjects, the commissioning of private decoration established the sultan’s legitimacy over his family. Reinforcing legitimacy was essential to Ottoman palace culture, even in spaces as intimate as the harem. Sultans were constantly threatened by usurpation and maintaining dominance over one’s successors was key. Murad III himself began his reign by ordering his five younger brothers to be strangled. [20]

Murad III faced uniquely difficult threats to his legitimacy and maintaining power was a key motivator throughout his 21 year-long rule. [21] Within the harem, those enacting his assassination and usurpment could very well be his own children. Concubines were also not outside the realm of suspicion, as some women in the harem were able to exert influence over Ottoman politics. It was not unheard of for women to also act as political players, as power-grabs on behalf of a son could place a woman in the illustrious Queen Mother position. [22] Maintaining control over family was constantly considered, even in palace art. According to architecture historian Christine Woodhead of the University of Durham, in response to his unique challenges and stresses, Murad III commissioned many elaborate pieces of palace art that “[provided] the sultan with a justification and reinforcement of his own status.” [23]

This tile’s importance is not fully realized without knowledge of its context within the rest of the bedchamber’s decorations. Identical tiles surround a meticulously constructed fountain embellished with its own intricate tiles. The aforementioned quranic verses that span the bedchamber are spelled out by intricate calligraphy and complement the tile’s palmettes with their bold blue hue. Gilded furniture, colorful stained glass windows and a grand tiled dome — connecting the sultan’s bedchamber to the heavens — further reinforce the room’s splendor with their complex and often natural ornamentation.

This tile is an excellent example of how extravagant design within Islamic art acted as a means to establish dominance of leadership. Its bold, colorful aesthetic, immaculate craftsmanship and larger temporal and spatial context reflects the unique splendor and power of the Ottoman ruler. Its extravagance acted as a visual reinforcer of Murad III’s rule and the sultans that rested in the chamber after him.

On Topkapi Palace, Islamic art expert Gülru Necipoğlu remarks: “These vast imperial palaces, conceived as architectural metaphors for three patrimonial-bureaucratic empires with their hierarchical organization of state functions… constituted elaborate stages for dynastic representation… each of them projected a distinctive royal image, invented with a specific theory of dynastic legitimacy in mind.” [24] While more private than Topkapi Palace as a whole, the bedchamber of Sultan Murad III still acted as an elaborate stage to support legitimacy. Within its intricacies were links to nature and God’s creation, but more so power itself. The frivolity of its complexity translated to a seemingly infinitely disposable amount of sultanic power. This implication, along with the decorations’ allusions to mandates of heaven, left little room to challenge the sultan’s position.

Given the tile’s setting within the bedchamber, the audience for this elaborate work was a small, yet personal one. Only those closest to the sultan would lay eyes on this piece. The message it told them was clear: this extravagant room is for a man above all others.

- “Tile with Floral and Cloud-band Design,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Accessed May 1, 2023. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/444897?deptids=14&ao=on&ft=palace&offset=0&rpp=40&pos=4.

- Gulsua Simsek and Geckinli A. Emel, “An Assessment Study of Tiles from Topkapi Palace Museum with Energy-Dispersive X-Ray and Raman Spectrometers,” Journal of Raman Spectroscopy 43. no. 7 (July 2012): 917, https://doi.org/10.1002/jrs.3108.

- Fanny Davis, Palace of Topkapi in Istanbul (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1970), 60.

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art, “Tile with Floral and Cloud-band Design.”

- V.B. Demirsar Arli, “Expounding on the ‘Figure’ Feature in Ottoman Tiles and Ceramics through the Figural Findings in Iznik Tile Kiln Excavations,” in 15th International Congress of Turkish Art, ed. Michele Bernardini, Alessandro T. Addei, and Michael Douglas S. Herida (Ministry of Culture and Tourism, Republic of Turkey, 2015), 234.

- Yahya Abdullahi and Mohamed R. Embi, “Evolution of Abstract Vegetal Ornaments in Islamic Architecture,” International Journal of Architectural Research 9, no. 1 (March 2015): 41.

- Nurdan O. Taskiran and Nursel Bolat, “Visual Discourse of the Clove: An Analysis on the Ottoman Tile Decoration Art.” International Journal of Research in Business and Social Science 1, no. 1 (2012): 23, https://doi.org/10.20525/IJRBS.V1I1.54.

- Abdullahi and Embi, “Evolution,” 36.

- Simsek and Emel, “An Assessment,” 918.

- Linda Carroll, “Could’ve Been a Contender: The Making and Breaking of ‘China’ in the Ottoman Empire,” International Journal of Historical Archaeology 3, no. 3 (September 1999): 177, http://www.jstor.org/stable/20852932.

- Carroll, “Could’ve Been,” 182.

- Carroll, “Could’ve Been,” 189.

- Taskiran and Bolat, “Visual Discourse,” 18.

- Gülru Necipoglu-Kafadar, “Framing the Gaze in Ottoman, Safavid, and Mughal Palaces,” Ars Orientalis 23 (1993): 304, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4629455.

- Nilay Özlü, “Single Palace, Multiple Narratives: The Topkapi Palace in Western Travel Accounts from the Eighteenth to the Twentieth Century,” The City in the Muslim World: Depictions by Western Travel Writers, ed. Mohammad Gharipour and Nilay Özlü (Taylor and Francis Inc., 2015): 168.

- Davis, Palace of Topkapi, 3.

- Necipoglu-Kafadar, “Framing,” 304-5.

- Necipoglu-Kafadar, “Framing,” 304.

- Hakan T. Karateke, “On the Tranquility and Repose of the Sultan,” The Ottoman World, ed. Christine Woodhead (Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon; New York: Routledge, 2011): 118.

- Gülru Necipoglu-Kafadar, Architecture, Ceremonial, and Power: The Topkapi Palace in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries (MIT Press, 1992): 164, https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/1358.001.0001.

- Christine Woodhead, “Murad III and the Historians: Representations of Ottoman Imperial Authority in Late 16th-Century Historiography,” Legitimizing the Order (Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 2005): 87, https://doi.org/10.1163/9789047407645_006.

- Necipoglu-Kafadar, Architecture, 159.

- Woodhead, “Murad III,” 97.

- Necipoglu-Kafadar, “Framing,” 303.

Bibliography

Abdullahi, Yahya, and Mohamed R. Embi. “Evolution of Abstract Vegetal Ornaments in Islamic

Architecture.” International Journal of Architectural Research 9, no. 1 (March 2015):

31-49.

Carroll, Linda. “Could’ve Been a Contender: The Making and Breaking of ‘China’ in the

Ottoman Empire.” International Journal of Historical Archaeology 3, no. 3 (September 1999): 177-90. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20852932.

Davis, Fanny. Palace of Topkapi in Istanbul. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1970.

Demirsar Arli, V.B.. “Expounding on the ‘Figure’ Feature in Ottoman Tiles and Ceramics

through the Figural Findings in Iznik Tile Kiln Excavations.” In 15th International Congress of Turkish Art, edited by Michele Bernardini, Alessandro T. Addei, and Michael Douglas S. Herida, 233-45. Ministry of Culture and Tourism, Republic of Turkey, 2015.

Karateke, Hakan T. “On the Tranquility and Repose of the Sultan.” In The Ottoman World, edited

by Christine Woodhead. Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon; New York: Routledge, 2011.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art. “Tile with Floral and Cloud-band Design.” Accessed May 1,

2023.

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/444897?deptids=14&ao=on&

;ft=palace&offset=0&rpp=40&pos=4.

Necipoglu-Kafadar, Gülru. Architecture, Ceremonial, and Power: The Topkapi Palace in the

Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries. MIT Press, 1992. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/1358.001.0001.

Necipoglu-Kafadar, Gülru. “Framing the Gaze in Ottoman, Safavid, and Mughal Palaces.” In Ars

Orientalis 23 (1993): 303-42. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4629455.

Özlü, Nilay. “Single Palace, Multiple Narratives: The Topkapi Palace in Western Travel

Accounts from the Eighteenth to the Twentieth Century.” In The City in the Muslim

World: Depictions by Western Travel Writers, edited by Mohammad Gharipour and Nilay Özlü, 168-88. Taylor and Francis Inc., 2015.

Simsek, Gulsua, and A. Emel Geckinli. “An Assessment Study of Tiles from Topkapi Palace

Museum with Energy-Dispersive X-Ray and Raman Spectrometers.” Journal of Raman

Spectroscopy 43. no. 7 (July 2012): 917-27. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrs.3108.

Taskiran, Nurdan O., and Nursel Bolat. “Visual Discourse of the Clove: An Analysis on the

Ottoman Tile Decoration Art.” International Journal of Research in Business and Social

Science 1, no. 1 (2012): 18-28. https://doi.org/10.20525/IJRBS.V1I1.54.

Woodhead, Christine. “Murad III and the Historians: Representations of Ottoman Imperial

Authority in Late 16th-Century Historiography.” In Legitimizing the Order: The Ottoman Rhetoric of State Power, edited by Hakan T. Karateke and Maurus Reinkowski (Brill, 2005): 85-98.