The Süleymaniye Mosque - Catalogue Entry

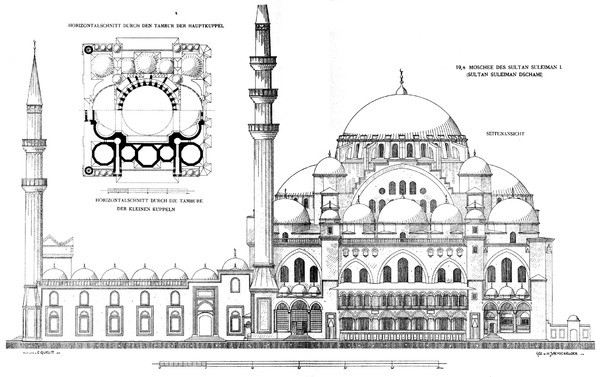

The Süleymaniye Mosque, located in present-day Istanbul, Turkey, is seen as a culmination of Ottoman architecture. Built by Ottoman Chief architect Mimar Sinan for Sultan Süleyman the Magnificent, the Süleymaniye Mosque is known today for its numerous domes, towering minarets, and spacious interiors. With a layout modeled after the Hagia Sophia, the Süleymaniye complex consists of: the mosque with a large courtyard surrounding it, one central dome in the center of the mosque with numerous smaller domes surrounding the structure, and four minarets accompany the mosque, linking the mosque to the power of Sultan Süleyman. On the outside of the courtyard there was an elementary school, five madrasas, a hospital, guesthouses, bathhouses, storefronts, and a college[i]. The Süleymaniye complex was designed as a grand center for higher learning as well as a center for prayer and gathering. As seen on the inscriptions on the exterior of the mosque, construction began in 1550 CE with the construction of much of the mosque finishing in 1557 CE with its inauguration as Istanbul’s Friday Mosque. The mosque was the largest of Sinan’s mosques at its completion with an area of 136 x 86 cubits and a dome with a diameter of 36 cubits[ii]. The mosque itself is primarily made of three types of stone: limestone, firestone, and Proconnesian marble[iii]. Floral Iznik tiles, handcrafted carpets, and stained-glass, detail the spacious interior of the mosque[iv]. A linked interior and exterior provide a unique and dynamic flow throughout the complex. Through the combination of these architectural and stylistic elements, Sinan created a mosque that redefined Ottoman architecture while also competing with the Byzantine Hagia Sophia.

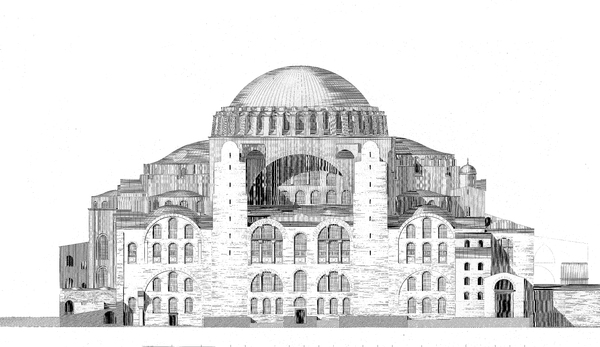

Following the Ottoman conquest and relocation of its capital to Istanbul, Turkey, Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent explored ways to further Ottoman rule over the previous Byzantine population. Although he destroyed the Church of the Holy Apostles, the Byzantine Hagia Sophia was left standing due to its prevalence as the city’s current Friday Mosque. During this time Mimar Sinan was the chief architect for the Ottoman empire. Sultan Süleyman commissioned Sinan to construct three imperial mosques: the Şehzade mosque, the Süleymaniye mosque, and the Selimiye mosque. The Süleymaniye mosque, named after its patron Sultan Süleyman the Magnificent, was Sinan’s attempt to rival the Hagia Sophia. Sinan uses the Süleymaniye mosque to refine the Hagia Sophia aesthetic of previous sultanic mosques, without directly competing with the Hagia Sophia[v]. This can be seen in the strong similarities of the plans for both the Hagia Sophia and the Süleymaniye. The dome on the Hagia Sophia was also larger, coming in at approximately 42 cubits [vi]. It was not until Sinan’s next mosque, the Selimiye, that he bested the Hagia Sophia.

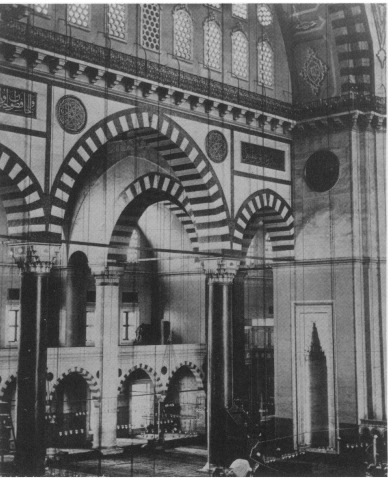

The Hagia Sophia was an architectural masterpiece of Byzantine culture. In his earlier manuscripts, Sinan refers to the Hagia Sophia as an unmatched masterpiece without equal in the world[vii]. The Hagia Sophia has one central and multiple semi-circle domes surrounding the central dome. The weight of the Hagia Sophia is supported through buttressed facades. The exterior of the Süleymaniye mosque was similar, due to Sinan designing the Süleymaniye mosque with the layout of the Hagia Sophia but uses Ottoman architectural elements to redefine the Ottoman style of sultanic mosques. There is a large central dome, but it replaces any semicircular domes with smaller complete domes. The central dome is also better supported on the Süleymaniye through a pyramidal massed design of the walls[viii]. Moving to the interior of the Hagia Sophia, space vanishes into the dark boundary of the enclosure creating a dim, mysteriously lit area covered in glittering gold[ix]. The interior of the Süleymaniye mosque is composed of 249 windows that span across the entirety of the main room, illuminating the room but also providing a more unified space than inside the Hagia Sophia[x]. The central dome of the Süleymaniye mosque not only looks perfect to the viewer’s eyes, but it also is mathematically perfect and symmetrical when examined using fractal patterns[xi]. As a symbol of perfect and infinite symmetry, Sinan constructed a perfect domed structure for the Süleymaniye mosque, whereas the Hagia Sophia’s dome is elliptical. The Süleymaniye dome is covered in beautiful blue Iznik tile work with marble covering most of the rest of the building’s interior. This gives the perception of an illuminated space due to the number of windows, white marble structure, and the Iznik tiles which differs from the dimness of the Hagia Sophia. Finally, Sinan uses a unique understanding of human scale to create an extravagant size ratio in the interior[xii]. Sinan regarded himself as having created a neo-Hagia Sophia Ottoman style with the creation of the Süleymaniye mosque[xiii]. He refined past Ottoman architectural achievements while also innovating his new style.

Materials for the Süleymaniye mosque were gathered from all reaches of the Ottoman empire. The three main stones used, marble, firestone, and limestone, were all gathered in traditional manners, but there was a large collection of architectural elements taken from ancient cities and contemporary buildings[xiv]. The final interior consists of 8 grand pillars: 4 marble pillars and 4 granite pillars. The four granite pillars were 9.1 meters in height and sourced from past structures in Alexandria, Constantinople, and Baalbek[xv]. Such a feat of transportation required monumental financing and logistical planning. In total the cost of the Süleymaniye mosque was 54,096,000 aspers, with a substantial part of that used for the acquisition and transportation of stone[xvi]. Sinan’s use of these massive pillars is both structural but also for aesthetic looks. These pillars were the support for much of the structure, including the dome, while also allowing for the creation of one unified space inside of the mosque.

One of the most impressive aspects of the Süleymaniye mosque is its scale. At the time of its completion, the Süleymaniye mosque was the largest mosque to date built by Sinan. The Süleymaniye mosque has external and internal symmetry that draws the viewer’s eyes upwards towards the large central dome. Sinan’s use of pillars to support the structure, instead of numerous buttresses as seen in the Hagia Sophia, creates a large unified internal space. Accompanied by the 249 windows spanning the entire structure, the internal space radiates a feeling of paradise. Throughout the entire mosque, Sinan uses a dynamic between the size of architecture and human scale to emphasize the grandeur of the mosque without the use of much unnecessary decorations. This is mainly seen in the large rectangular size of the mosque, the large central dome, the towering minarets, and the large pillars holding up the interior of the mosque. Each architectural element furthers Sinan’s attempt to compete with the Hagia Sophia, while also competing with previous Ottoman Sultanic mosques.

The Süleymaniye mosque is a perfect example of extravagance through the use of size and scale. As aforementioned, Sinan designed the mosque with a similar layout as the Hagia Sophia to show his architectural mastery of the mosque architecture. Although he does not best the Hagia Sophia with the Süleymaniye Mosque, he accomplishes his goal of redefining the Ottoman architectural style while maintaining a similar architectural plan as the Hagia Sophia. Upon its completion in 1557 CE, the Süleymaniye mosque was Sinan’s largest structure, most expensive project, and most stylistically unique. Sinan used stone from across the Ottoman empire and even repurposes massive pillars from across the Mediterranean Sea. Sinan succeeds in creating a spacious unified, illuminated interior fit to accompany any of the Ottoman societies needs for the space as a mosque or community center. Sinan succeeded in building a structure that is instantly recognizable due to its sheer scale, but also a space that would be used by the Ottoman and Turkish communities for hundreds of years to come.

[i] Gülru Necipoğlu, The Age of Sinan, (London: Reaktion, 2011), 205.

[ii] Gülru Necipoğlu, The Age of Sinan, 120.

[iii] İlknur Aktuğ Kolay and Serpi̇l Çeli̇k, “Ottoman Stone Acquisition in the Mid-Sixteenth Century: The Süleymani̇ye Complex in Istanbul,” Muqarnas 23 (2006): 255.

[iv] Gülru Necipoğlu, The Age of Sinan, 215.

[v] Gülru Necipoğlu, The Age of Sinan, 139-140.

[vi] Gülru Necipoğlu, The Age of Sinan, 120

[vii] Gülru Necipoğlu, “Challenging the Past: Sinan and the Competitive Discourse of Early Modern Islamic Architecture,” Muqarnas 10 (1993): 170-172

[viii] Gülru Necipoğlu, “Challenging the Past,” 173-174.

[ix] Doğan Kuban, “The Style of Sinan’s Domed Structures,” Muqarnas 4 (1987): 84.

[x] Gülru Necipoğlu, The Age of Sinan, 215.

[xi] Özgür Ediz and Michael J. Ostwald, “The Süleymaniye Mosque: a Computational Fractal Analysis of Visual Complexity and Layering in Sinan's Masterwork,” Architectural Research Quarterly 16, no. 2 (2012): 179.

[xii] David Gebhard, “The Problem of Space in the Ottoman Mosque,” The Art Bulletin 45, no. 3 (1963): 274–75

[xiii] Gülru Necipoğlu, “Challenging the Past,” 172.

[xiv] Kolay and Celik, “Ottoman Stone Acquisition,” 255-256.

[xv] Gülru Necipoğlu, The Age of Sinan, 221.

[xvi] Gülru Necipoğlu, The Age of Sinan, 122-123.

Bibliography

Ediz, Özgür, and Michael J. Ostwald. “The Süleymaniye Mosque: a Computational Fractal Analysis of Visual Complexity and Layering in Sinan's Masterwork.” Architectural Research Quarterly 16, no. 2 (2012): 171–82. doi:10.1017/S1359135512000474.

Gebhard, David. “The Problem of Space in the Ottoman Mosque.” The Art Bulletin 45, no. 3 (1963): 271–75.

Kolay, İlknur Aktuğ, and Serpi̇l Çeli̇k. “Ottoman Stone Acquisition in the Mid-Sixteenth Century: The Süleymani̇ye Complex in Istanbul.” Muqarnas 23 (2006): 251–72.

Kuban, Doğan. “The Style of Sinan’s Domed Structures.” Muqarnas 4 (1987): 72–97.

Necipoğlu, Gülru. “Challenging the Past: Sinan and the Competitive Discourse of Early Modern Islamic Architecture.” Muqarnas 10 (1993): 169–80.

Necipoğlu, Gülru. The Age of Sinan : Architectural Culture in the Ottoman Empire. London: Reaktion, 2011.