Ram's Head Dagger Catalogue Entry

Extravagance and impracticality of the weapons in this exhibit are what make them distinctive as symbols of position and power. A musket , for example, commissioned and created specifically for a sultan, never fired, serving to warn enemies against the instigation of conflict. This underlying display of lofty control is the cornerstone this exhibit is based upon. The idea that at some point in history, especially between the 16th and 18th centuries, the idea and threat of violence was an effective means of communicating intention is powerful.

Weaponry and armaments made in such spectacular fashion, deliberately showing intricate detail work and craftsmanship, was never intended to be used in war. Take for example, this chain mail and plate shirt. The plate is inscribed with religious imagery and symbols and is made of gold. Gold, an expensive and beautiful material, is not typically used in armor due to the additional unnecessary weight and pliability that makes it impractical.This level of impracticality borders on arrogance, as the shirt was worn by the emperor at the time, Sahah Jahan, and the more valuable and weaker points of the armor cover the most important organs, as most plates in armor did at the time. It denotes a confidence and deep faith in both the person who created the shirt, and the likelihood that would-be attackers are not likely to attack. The yatagan, a short sword, to the left, is of ceremonial quality, not intended for use in battle, made with various precious metals and materials ranging from silver and gold to ivory and ruby, and, rather than being used as a weapon as is the nature of a short sword, it is used as a symbol of Ottoman wealth and power. Because of this, it is clear that extravagance in weaponry is meant to be a taunting display of power and social class.

However, there are also weapons crafted with both practicality and function in mind. This dagger is noteworthy for both the quality of its production and the beautifully intricate patters it is adorned in. It is decorated in precious stones set in using the kundan method, which is a method of inlaying stones in malleable gold, which allows them to be set in any number of intricate patterns (Jeweled and Enameled). This method is still used in India today, typically to create jewelry that is unique, and beautiful. Enameling became part of the jewelry process with the intention of a private design that would make any given piece one of a kind, the enameling private to the wearer. This method was most likely brough to India from Europe (V&A). In both of the following daggers, notable from Mughal India, the precision and accuracy must be noted. The Mughal style, both of carving and of setting, enameling, and inlaying stones, is known for its clear attention to detail and biological accuracies, to the point that it becomes easy to distinguish different species from the carvings, indicating a live model, or an incredibly practiced hand. The practice of these arts is incredibly precise, as most of it is done freehand, requiring years of practice and skill, which is why the craft is passed down through families, fathers teaching sons how to create art using this method from a young age, so that they are skilled craftsmen by the time they truly begin their work (Vibhuti Sachdev).

While the hilt of it looks egregious, the blade is steel, and created with unique strength due to the method of creating it. The crucible steel technique, named for the mold used for the blades, began in India before spreading through Asia . Blades like this were renowned for their high quality, which made them popular political gifts (Khadeeja Althagafi). In the Mughal courts of India, daggers like the Ram’s Head Dagger and this one (left), carved from nephrite, were awarded to high achieving military officials and worn as “dress accessories indicating royal favor,” (Dagger with Hilt). Once Islamic influence hit the culture of the dagger, both the appearance and functions of the daggers shifted to reflect the religious obligations of clothing, which discourage elaborate clothing and accessories. The dagger was considered a tool and therefore exempt from these requirements, which led to the development of far flashier and notable hilt designs and accessories (Althagafi). Note the difference between the two daggers pictured here. They are made in different ways, one carved, the other carefully inlaid. The Ram’s Head Dagger is made with more eye-catching materials, the cross guard featuring intensely detailed work depicting two people leaning against it; the Bull’s Head Dagger is, conversely, far simpler, made of one material and done so finely, but in a way that is less obvious at first glance. For comparison, images of the two hilts are to the right.

Mughal emperor Shah Jahan was instrumental in establishing the long-standing tradition of including floral imagery like we see in the cross guard of the Bull’s Head Dagger and in the pommel of the Ram’s Head Dagger. The emperor in his time was fond of horse- and antelope-headed daggers such as this one (right), and so employed many skilled craftsmen to create them (Stephen Markel, 26). The tradition of using flora and fauna in portable art was most notable in the 16th century Mughal dagger and sword hilts, which often ended in the shape of an animal head. The figures of nilgai, rams, and others were favored. Nilgai are the largest species of antelope in Asia, and are commonly referred to as blue bulls, which created the model and basis of the Bull’s Head Dagger. The Mughal style came from a long period of reshaping the weapon standards and forms while drawing designs and styles from different cultures, Islamic and Hindu designs specifically (Markel, 31-32). The traditions and skills used by Mughal artists can be plainly seen in the Ram’s Head Dagger. The floral pattern adorning the pommel of the blade is detailed, precise, and symmetrical, as is the one on the cross guard.

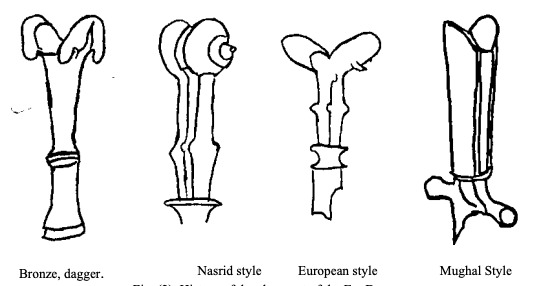

An early version of the daggers of this design is the Ear Dagger. This was a kind of dagger that had no specific artistic preferences it was beholden to, but rather many of them, as it drew from various cultures at the time. This style of dagger is notable for its distinct pommel, from which protruded two curved ‘ears’. The earliest style of this blade was the Nasrid style, approximately originating in the 14th century (Hamada Thabet Mahmoud, Rabei Ahmed Sayed 186). The pommel of the handle helped to stabilize the blade in its hilt, while making it easier for soldiers to perform its function of stabbing. This style of dagger became popular around Europe as well. Over a long period of time, the ears of the handle became closer together, to the point that they made it into a single, curved end. That curved end would eventually form the basis for artistic liberty to be taken by the Mughals, who, as previously discussed, were very fond of animal head hilts. Because of the natural structure of a skull, the daggers maintained their curve. Where initially, the daggers depicted decorations that indicated its use, the Mughals introduced the floral patterns and animal heads that create a distinction between Ear Daggers and the Animal Headed Daggers in time (Mahmoud, Sayed, 202).

The sort of Ear Dagger present in the image above under the Mughal Style is unique in that it is the most streamlined version of the Ear Dagger. As the design became popular, traditional materials began to develop. The daggers pommels were made typically of either nephrite or metal, most commonly gold. This led to the popular use of the kundan technique. As mentioned earlier, stones are pushed into gold to set them. The gold must be purified, first, and is then “malleable at room temperature”, which makes it easier to push stones into (Mohammed Khalil Ibrahim, 207). Most daggers created in this style are preserved as they were made, which indicates the durability of this style of work despite the malleability of the metal.

The propensity in this time period for weapons that would serve both functional and social purposes is clear. The level of skill, as well as degree of luxury and detail increases temporally as the social demands set in. The quality of materials also evolves to be incredibly durable, lasting in perfect and near-perfect condition to this day. The significance of this is the look we get into the cultural norms and priorities of that time period. The religious connotations are some of the most important to understand and consider. In the Western world the religion with the most influence is Christianity, and the culture reflects that in ways most people within it would not be able to identify, especially how it has shaped the cultures of today. While it hasn’t had nearly the same amount of time to develop compared to the 16th century Islamic influences on art in India and the Middle East, it has had an impact. Due to the longevity of the items we can observe and the evolved culture, patterns arise such as previously mentioned with the changing of style and purpose of wearing daggers. This gives us a clearer look into history, one that is in many ways disregarded in our culture.

Bibliography

Althagafi, Khadeeja. “The Art of Southern Arabian Daggers: An Emblem of Pride Masculinity and Identity.” Arts 11, no. 3 (2022): 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts11030053.

“Dagger with Hilt in the Form of a Blue Bull (Nilgai).” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, n.d. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/453253.

Ibrahim, Mohammed Khalil. Islamic Arms and Armor: The (One Thousand One) Collection. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2018: 210-216.

“Jeweled and Enameled Ram's Head Dagger.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Accessed March 23, 2023. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/452103

Mahmoud, Hamada Thabet, and Rabei Ahmed Sayed. “Ear Dagger From the 14th to the 19th Centuries: an Artistic Functional Study of Sampies.” Annual peer-reviewed journal issued by the Faculty of Archaeology, Fayoum University 10, no. 10 (2023): 186-202.

Markel, Stephen. “The Use of Flora and Fauna Imagery in Mughal Decorative Arts.” The Decorative Arts. Marg Publications, 1999. https://d1wqtxts1xzle7.cloudfront.net/31649921/MARKEL_Flora_and_Fauna_Imagery_-_Copy-libre.pdf?1392349204=&response-content-disposition=inline%3B+filename%3DThe_Use_of_Flora_and_Fauna_Imagery_in_Mu.pdf&Expires=1682993756&Signature=H-VogaQ049evBueFk2BqTa7GL~pNVnVX0HYROueKPYpfwn9d0di-KeKWJLrGmgTP0ZCTizDoigm6n54OHe7NX79q3aSoHnpErYAzNnu-KJ-XEa0DwDaaXx2BxiCsx4Zcx0ccX2o0roX5PPykTZxPfHVxA~M18nO9hLAv0q-oUNmBK7THu5jRsAxGoed0af5p612EC7paXOiiAWmTaxiBy4MD8m5xvqFJVNyCFi9JYUs-Aje5KBrwVoU~PXfFQNfisIQRgmpRdkD9CStFl7vjo3kRF7ml6VBJk-C~Y44MHppWNiq~u7vJJnJMEZ0B6PY3hQwAh~BRyp5xc9tWtqT3mQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAJLOHF5GGSLRBV4ZA.

Sachdev, Vibhuti. “In a Maze of Lines: The Theory of Design of Jaalis.” South Asian Studies 19, no. 1 (2003): 141–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/02666030.2003.9628626.

“V&A · Traditional Indian Jewellery Making.” Victoria and Albert Museum. Accessed March 23, 2023. https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/traditional-indian-jewellery-making.