Khirbet al-Mafjar Catalog Entry

Khirbet al-Mafjar is an extravagant Umayyad complex located outside of Jericho, Palestine. Due to its grand features and location, it is known to be one of the many Umayyad desert palaces, a type of living complex that the Umayyad dynasty is known for. A desert palace follows a certain pattern of construction which takes inspiration from Roman villa architecture. At their center is a large portico court that opens from a large entrance hall and is flanked by numerous rooms for professional or personal use. Outside of the main palace are other features like bath halls, mosques, and lavish gardens.[i] The purpose of these desert palaces, also known as qasrs, has been speculated across art historians and archeologist as they are unsure if they acted as residential palaces or palaces of leisure. In the case of Khirbet al-Mafjar, the question of purpose becomes even more intriguing after looking at its extravagantly large and beautifully decorated audience/bath hall.

[i] Grabar, Oleg. “Umayyad Palaces Reconsidered.” Ars Orientalis 23 (1993): 93-108.

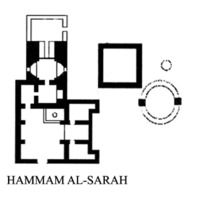

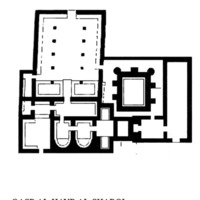

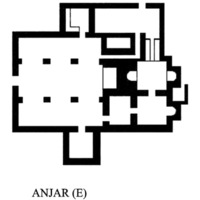

The way the Umayyad dynasty constructed their bath halls led them to become very important aspects of social and political life during this period. Each bath house followed a common template: an apodyterium (audience hall), frigidarium (cold room), tepidarium (warm room), and caldarium (hot room). During the late antiquity period the Romans were the first to explore the idea of changing this normal. Enlarging their apodyteria and downsizing the actual bathing rooms allowed the bath halls to become places of leisure and enrichment where a social culture could flourish.[i] This configuration ultimately inspired the architectural basis for Umayyad bath halls as many, like Khirbet al-Mafjar, feature a grand audience hall. There are numerous other baths that can encapsulate this formula of architecture, like those at ‘Anjar and Qasr al-Hayr al-Sharqi, but they are still unable to match up to the extremity of proportion between the audience hall and the bathing rooms at Khirbet al-Mafjar[ii].

[i] Arce, Ignacio. “The Umayyad Baths at Amman Citadel and Hammam Al-Sarah Analysis and Interpretation: The Social and Political Value of the Umayyad Baths.” Syria 92, (2015): 133-168.

[ii] Arce, “The Umayyad Baths at Amman Citadel and Hammam Al-Sarah Analysis and Interpretation: The Social and Political Value of the Umayyad Baths,” 167.

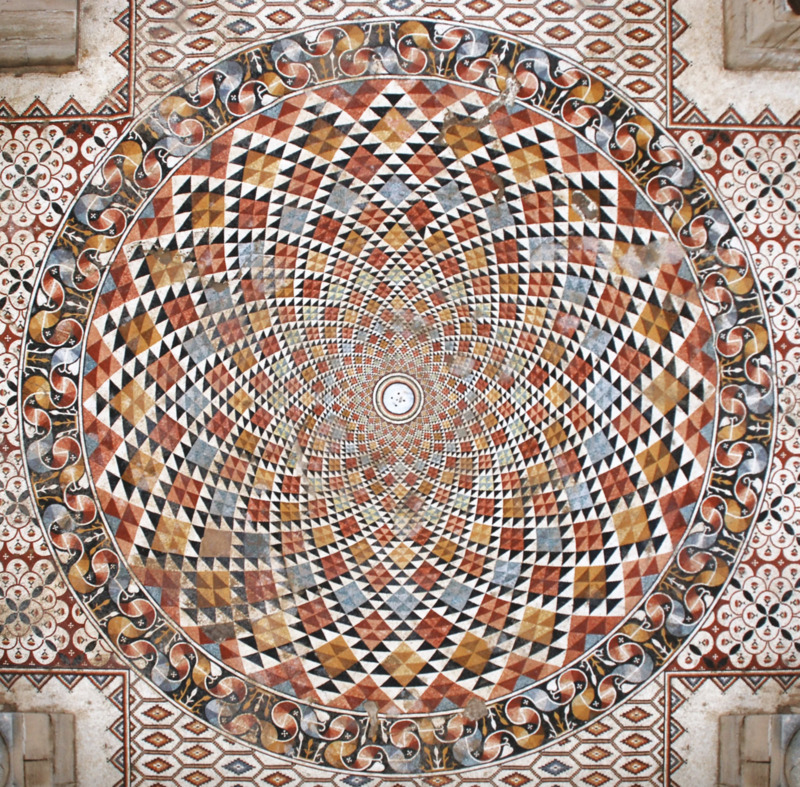

To understand the extravagant scale of Khirbet al-Mafjar it can be compared to another bath hall, Hammam al-Sarah. This bath had a main audience hall that was 7.82-meters by 9.1-meters a very typical size for an audience hall. The Khirbet al-Mafjar audience hall was twelve times greater than that, spanning a 30 by 30-meter area. Along with the size there are unique stylistic features that elevate the design of this complex, like the triplet hemi-domed exedras that were found on each of the four walls and the 20-meter long by 1.5-meter-deep swimming pool that was supposedly added on later. [i] As these features were quite fascinating the most notable aspect of this audience hall was the mosaic carpet that spanned the entire 30x30m floor. This mosaic carpet, being unlike any other, is reportedly the largest surviving mosaic from the late antiquity period.[ii] With a medallion as its center panel, the carpet consists of 38 different segments pieced together to form one cohesive mosaic that is only interrupted by the pool and column bases. These mosaics were beautifully colored and created in geometric and floral patterns that greatly mimicked those of Roman descent.[iii]Besides the main floor of the audience hall there were also separate rooms with their own mosaics as well, like the diwan, which contained the great “Tree of Life” mosaic. This specific mosaic has many different interpretations, from being inspired by Solomon’s throne, to the peace and violence representing an erotic encounter written about by al-Walid ibn Yazid, protection, wild versus domestic world, religious paradise, and so on.[iv]

[i] Hamdan, Taha, and Donald Whitcomb. The Mosaics of Khirbet el-Mafjar: Hisham’s Palace. Ramallah: Palestinian Department of Antiques and Cultural Heritage, 2014; Chicago: The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, 2015.

[ii] Hamdan, and Whitcomb. The Mosaics of Khirbet el-Mafjar: Hisham’s Palace, 23.

[iii] Grabar, Oleg. “The Umayyad Palace of Khirbat al-Mafjar.” Archaeology 8, no. 4 (December 1955):228-235

[iv] George, Alain and Andrew Marsham. Power, Patronage, and Memory in Early Islam: Perspectices on Umayyad Elites. New York: Oxford University Press, 2018.

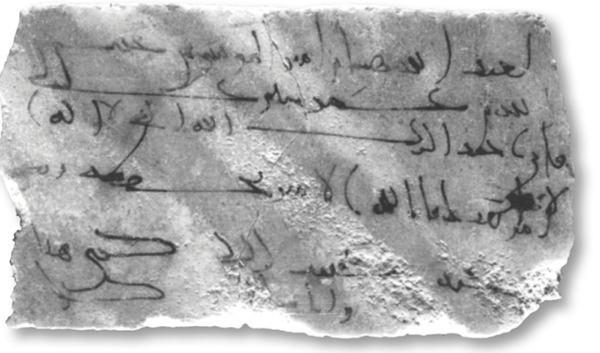

The extravagance of this audience room inspired many different beliefs and opinions in the those who studied it. The beginning of Khirbet al-Mafjar’s excavation started with Dimitri Baramki, an archeology professor at the American University of Beirut, in the mid to late 1930s. His excavations focused more on the pottery in the southern area of the site, in which he found a stone inscription that stated, “Hisham, commander of the faithful”.[i] This finding would be very important as it gave some evidence to who this palace could be made for, Hisham ibn ‘Abd al-Malik. Baramki also made note of the specific stylistic elements of the palace’s architecture, that along with the inscription would help to name this complex as Qasr Hisham.[ii] A few years later in 1944, archeologist Robert Hamilton began excavating Khirbet al-Mafjar, leading to some of the more famous but problematic interpretations of its extravagance.

[i] Whitcomb, Donald. “The Jericho Mafjar Project: Palestine-University of Chicago Research at Khirbet el-Mafjar.” In Digging Up Jericho: Past, Present, and Future, edited by Rachael Thyrza Sparks et al, 247-254. Oxford: Archeopress, 2020.

[ii] Whitcomb, “The Jericho Mafjar Project: Palestine-University of Chicago Research at Khirbet el-Mafjar,” 249.

Robert Hamilton initially began his studies by examining the stone carvings within the palace, but eventually moved to interpreting the decorative elements of the audience hall. The bath hall contained various mosaics and stuccos that provided evidence for its effect on social life in the city of Jericho, however, because of Hamilton’s orientalist beliefs this only contributed to a false narrative that is still believed today. Many of the stucco sculptures found within the bath hall were depictions of human or womanly figures that are nude from the waist up.[i] With the inscription found earlier, Hamilton came up with the theory that this palace could not have been built for Umayyad Caliph Hisham ibn ‘Abd al-Malik, but for his nephew al-Walid ibn Yazid.[ii] This belief stemmed from the fact that Hisham ibn ‘Abd al-Malik was al-Walid ibn Yazid’s uncle and that al-Walid was known for his lively poetry and eccentric “playboy”-esq lifestyle. From then on, the bath hall was widely believed to be al-Walid’s palace for leisure and sexual indulgence.[iii]

[i] Soucek, Priscilla P. “Solomon’s Throne/Solomon’s Bath: Model or Metaphor?” Ars Orientalis 23 (1993):109-134.

[ii] Whitcomb, “The Jericho Mafjar Project: Palestine-University of Chicago Research at Khirbet el-Mafjar,” 249.

[iii] Whitcomb, “The Jericho Mafjar Project: Palestine-University of Chicago Research at Khirbet el-Mafjar,” 249.

Another interesting interpretation comes from Islamic art historian, Priscilla P. Soucek, offering that the bath hall’s extravagance was inspired by the great Prophet King Solomon. King Solomon was a very popular figure within the Islamic religion. He was known as a divine profit who God gave the ability to control the wind, communicate with many forms of being, and command demons to work for him[i]. With the help of the wind and demons, Solomon was able to travel far distances on a flying platform with an entire entourage of humans and animals. He sat upon a great throne made of ivory and gold, with two lions at his side and birds flying over him providing shade to all.[ii] Besides being a grand spectacle with divine powers, it was believed that Solomon was also linked to the creation of bath halls. Her main beliefs rest upon the location of Khirbet al-Mafjar, the alleged Solomonic imagery in the bath porch façade, the tree of life mosaic in the diwan, and the placement of the sculptural décor that depicted women, men, birds, and animals.[iii]

[i] Soucek, “Solomon’s Throne/Solomon’s Bath: Model or Metaphor?” 112.

[ii] Soucek, “Solomon’s Throne/Solomon’s Bath: Model or Metaphor?” 112.

[iii] Soucek, “Solomon’s Throne/Solomon’s Bath: Model or Metaphor?” 123.

With today’s advancements in the excavation of the palace, there is still wide speculation on who built this palace and why the bath hall needed to be so extravagant. Another theory presented by Hana Taragan suggests that the Umayyad dynasty built this palace to validate the power that they acquired so quickly.[i]Considering the heavy Roman and Byzantian influence seen in the architecture and mosaic pattern and the dominant symbolism in the tree of life mosaic, it makes sense to assume that the size and extravagance of this bath hall demonstrates the new power of the Umayyad dynasty and provide its people with a beautiful area to celebrate their pride and social lives.

[i] Taragan, Hana. “Atlas Transformed-Interpreting the ‘Supporting’ Figures in the Umayyad Palace at Khirbet al Mafjar.” East and West 53 no. ¼ (December 2003): 9-29.

Despite the numerous differing opinions about this complex, it holds a very significant importance to modern day Palestine and Islamic cultural. The feats accomplished in the construction of this palace allow it to be a great source of pride to Palestine. In recent years further excavation and projects have helped to turn this great complex into a museum site that not only benefits Palestine monetarily but also helps to educate others of the rich architectural history of Islam.[i] There are still further improvements and excavations that can be made towards the conservation and understanding of this site but as of right now its scale and extravagance works to benefit the Islamic and Palestinian communities.

[i] Green, Jack. “The Hisham’s Palace Site and Museum Project.” In Digging Up Jericho: Past, Present and Future, edited by Rachel Thyrza Sparks et al, 299-310. Oxford: Archaeopress, 2020.

Bibliography

Arce, Ignacio. “The Umayyad Baths at Amman Citadel and Hammam Al-Sarah Analysis and Interpretation: The Social and Political Value of the Umayyad Baths.” Syria 92, (2015): 133-168.

George, Alain and Andrew Marsham. Power, Patronage, and Memory in Early Islam: Perspectices on Umayyad Elites. New York: Oxford University Press, 2018.

Grabar, Oleg. “The Umayyad Palace of Khirbat al-Mafjar.” Archaeology 8, no. 4 (December 1955):228-235

Grabar, Oleg. “Umayyad Palaces Reconsidered.” Ars Orientalis 23 (1993): 93-108.

Green, Jack. “The Hisham’s Palace Site and Museum Project.” In Digging Up Jericho: Past, Present and Future, edited by Rachel Thyrza Sparks et al, 299-310. Oxford: Archaeopress, 2020.

Hamdan, Taha, and Donald Whitcomb. The Mosaics of Khirbet el-Mafjar: Hisham’s Palace. Ramallah: Palestinian Department of Antiques and Cultural Heritage, 2014; Chicago: The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, 2015.

Soucek, Priscilla P. “Solomon’s Throne/Solomon’s Bath: Model or Metaphor?” Ars Orientalis 23 (1993):109-134.

Taragan, Hana. “Atlas Transformed-Interpreting the ‘Supporting’ Figures in the Umayyad Palace at Khirbet al Mafjar.” East and West 53 no. ¼ (December 2003): 9-29.

Whitcomb, Donald. “The Jericho Mafjar Project: Palestine-University of Chicago Research at Khirbet el-Mafjar.” In Digging Up Jericho: Past, Present, and Future, edited by Rachael Thyrza Sparks et al, 247-254. Oxford: Archeopress, 2020.