Qasr al-Mshatta Façade Catalogue Entry

The Qasr al-Mshatta was commissioned under the Caliph al-Walīd II during his brief reign from 743-744 CE. This desert palace is believed to be a winter residence and storage hall for al-Walīd II and his family, yet many scholars disagree over its exact purpose to this day. The palace as a whole is organized into a square structure with limestone masonry walls 1.5m thick and twenty-five towers creating its exterior. On the palace’s interior, the central tract is of great significance. The central courtyard leads to the reception hall, but in the southeast corner, there is a small mosque and its mihrab still visible in this qasr’s ruins. However, the reception hall room is the only part of the building architecturally complete. Mshatta’s reception hall includes a hallway reminiscent of a basilica and a throne room. This object is the palace’s southern main façade from both sides of the entrance gate. While this frieze is intricately decorated, the most decorated part of the façade correlates to the completed sections of this qasr dedicated to the caliph.[1]

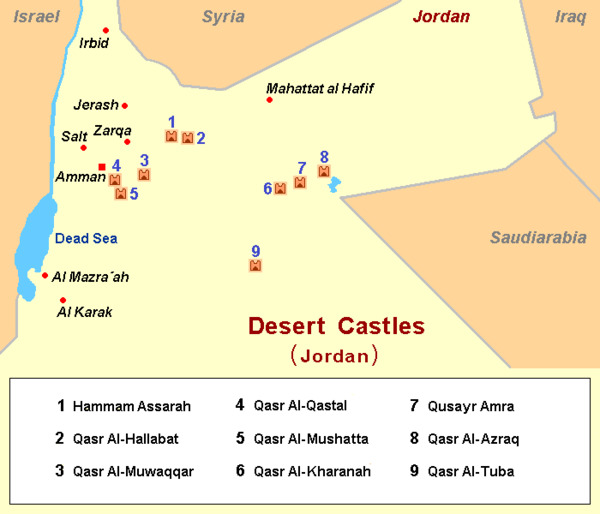

To better understand the significance of Qasr al-Mshatta, it is important to place this palace into context with other qasrs created by the Umayyads. Most Umayyad qasrs were built in fruitful regions of the steppe, grassland plains, typically located near the Euphrates, which often served as the main water source. Qasr location concentration was dependent on the caliph’s preferences. For example, Caliph Hisham (r. 724-743) preferred places like Raqqa, Balis, and Rusafa, whereas Caliph Yazid II (r. 720-724) and al-Walīd II preferred the Balqa, the central plain of Jordan. Qasr al-Qatal, Qasr al-Mshatta, Qasr al-Fudayn, Qusayr al-Amra, Qasr al-Muwaqqar, Qasr al-Kharana, and Qasr al-Hallabat were all located in the Balqa. In general, the two main purposes of qasrs were (1) to house non-religious family members of the caliph, such as evident in Qusayr Amra, or (2) to extend their power into the steppe visually. The majority of qasrs are built near trade/pilgrimage roads, connecting the Middle East to the Arabian Peninsula and to the western Arabia, where the Islamic holy cities of Mecca and Medina are. Along routes, nearby qasrs could serve as a safe haven for travelers on their journey. Qasrs could also be utilized as meeting places for the Umayyad caliphate and other significant individuals, such as Arab tribes in the Syrian desert.[2]

While each qasr is unique to its patron and location, this type of palace depicts similar characteristics of Umayyad sculpted ornament culture. Khirbat al-Mafjar, also known as Qasr Hisham, was commissioned by Caliph Hisham ibn Abd al-Malik in the Jordan Valley during his reign from 724-743 CE. Qasr al-Hayr West is located in the Syrian desert along the Damascus road and was also commissioned by al-Malik in 728-729 CE. Both of these Umayyad buildings follow the mosaics of the Dome of the Rock through its own way, separate from the architecture. While this is demonstrated through the panels throughout the Khirbat al-Mafjar and Qasr al-Hayr West, Mshatta’s large triangles expanded across the southern central frieze also depict this characteristic. Mshatta’s triangles also represent how Umayyad artists utilize simple geometric frames (i.e., squares, rectangles, circles, triangles) to create their architectural designs.

This is also demonstrated through Qasr al-Hayr’s panel rectangles. Shapes can be portrayed through both a large and small scale. This characteristic fosters the organization of Umayyad construction sites by providing basic geometric outlines. Lavish decorations of a variety of themes and motifs are also an aspect of Umayyad sculpted ornament culture. Themes and motifs can be classified as either geometric or vegetal ornaments. At the Khirbat al-Mafjar, borders, frames, balustrades, parapets, lintels, and windows depict geometric ornamentation. Qasr al-Mshatta’s intricate and extensive vines and Qasr al-Hayr West’s panel show vegetal ornamentation. All three buildings demonstrate architectural contrasts, but their differences and architectural individuality are aligned with the size of the empire.[3]

Although Qasr al-Mshatta displays characteristics of Umayyad sculpted ornament culture, it is significantly different from other Umayyad entities. Its structured geometric architectural plan of its squared flooring contrasts to Khirbat al-Mafjar’s disposition and to Qasr al-Hayr’s incongruencies. Other qasrs have significantly more decoration, themes, and designs; however, Mshatta’s structural organization and cohesion of its southern main façade is what makes this piece of Umayyad architecture distinct. Because cohesion was not prominent in Islamic architecture in the early eighth century, Mshatta is not non-Umayyad; rather, it can be viewed as the pinnacle of Umayyad stylistic progression.[4]

The Mshatta façade consists of two towers and two parts of equal size, making up the southern central entrance. Even though the façade entirety contains zigzag triangles, the left side of the façade is decorated with motifs depicting vegetation, animals, and mythical creatures, whereas the right-side lacks animal motifs. On the face of the western tower of Mshatta, two lion motifs are facing one another while drinking from a basin. Because the two lions mirror each other’s stances, facial expressions, and general features, they are believed to represent royal authority. In Umayyad architecture, scholars believe facing lions represent the Umayyad caliph.[5] Animals that are typically enemies are pictured together in pairings, and they share a drinking basin. Rosettes and vine tendrils wrap around the entirety of the frieze. Mythical creatures such as griffins and centaurs are also portrayed. However, centaurs are depicted as weaponless, which demonstrates aspired peace and unity. Empirical protection is also emphasized through simurghs, a mythical peacock dragon known for its powers of protection. On the right half of the entrance, the ornamentation is strictly vegetal. Based on Mshatta’s architectural floor plan, many scholars attribute the lack of animal and mythical creature motifs to respect for the mosque on the façade’s inside.[6]

The intricate detail of the Mshatta façade ornamentation is architecturally similar to Graeco-Roman-Byzantine and Sasanian building culture. On the western half of the façade, pairings of humans are reminiscent of scenes from Graeco-Roman scrolls. Additionally, mythical peacock depictions mirror a Persian simurgh, a half-dog and half-peacock creature, which were significant in Sasanian artwork through the sixth and seventh centuries. While similarities are evident on the western half of the façade, the eastern half shows even more Sasanian prominence through the winged palmettes. Because of the stark resemblance between Mshatta’s ornamentation and Graeco-Roman-Byzantine and Sasanian building culture, many scholars believe these designs were deliberate. The connection between these cultures and their architecture to Mshatta’s façade alludes to Mshatta being an early Eastern and Western architectural synthesis, along with being a visual of Umayyad shifting stylistic progression.[7]

While Qasr al-Mshatta is significant to Umayyad architectural development, it also played a prominent role in Caliph al-Walīd II’s legitimacy as a ruler. Al-Walīd b. Yazīd is known as the most infamous caliph of the Umayyad dynasty. He is described as deviant, a moral failure, and lacking ability to manage tribal disagreements. When he did tend to his caliphate duties, he is described as doing so only for the sake of pleasure or revenge. Otherwise, al-Walid II’s focus was dedicated to women, wine, and pleasure. Overall, al-Walīd II lacks a sophisticated and respected image as an Umayyad caliph.[8] However, by commissioning the Qasr al-Mshatta along the route to Mecca and Medina, al-Walīd II attracts people to attend through creating caravan stops for travelers. In doing so, al-Walīd II created another space where he could facilitate trade routes and indulge himself as a ruler further.[9] By placing this qasr in a steppe in Amaan, Jordan, al-Walīd II visually highlights his power as caliph through architectural size, intricacy, and ornamentation. This palace was meant to appear distinguished and reputable so al-Walid II could meet with other tribal leaders, which demonstrates al-Walīd II’s aspired legitimacy as a ruler.[10] The animal and mythical creature motifs and their meanings also uplift al-Walīd II’s rule as caliph. However, Qasr al-Mshatta was never complete due to Caliph al-Walīd II’s assassination in 744 CE.

Qasr al-Mshatta relates to the theme of extravagance through its excessive ornamentation, its connections to Graeco-Roman-Byzantine and Sasanian culture, and its impact on Umayyad stylistic artwork. The qasr’s extravagance legitimizes Caliph al-Walīd II as a ruler through its complex and thoughtful vegetal, animal, and mythical motifs and their meanings. Mshatta also symbolizes a shift in overall architecture, serving as a significant connection between Eastern and Western architectural decorations and ornamentations. Compared to other Umayyad qasrs, Qasr al-Mshatta can be viewed as the pinnacle of Umayyad stylistic progression, making this palace and its façade all the more extravagant.

[1] Townson, “Mshatta’s Façade and the Viewer” in Made for the Eye of One Who Sees: Canadian Contributions to the Study of Islamic Art and Archaeology (Montreal, Quebec: McGill’s University Press, 2022), 26-27.

[2] Ballain, “Country Estates, Material Culture, and the Celebration of Princely Life: Islamic Art and the Secular Domain” in Byzantium and Islam: Age of Transition, 7-9th Century (New York, NY: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2012), 200.

[3] Ettinghausen, Richard, Oleg Grabar, and Marilyn Jenkins-Madina, Islamic Art and Architecture 650-1250 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2001), 50-51.

[4] Grabar, “The Date and Meaning of Mshatta” in Dumbarten Oaks Papers 41 (1987): 244.

[5] Townson, “Mshatta’s Façade and the Viewer,” 35.

[6] Townson, “Mshatta’s Façade and the Viewer,” 42-44.

[7] Birk, et. al., Using Images in Late Antiquity (Oxford, England: Oxbow Books, 2014), 291-293.

[8] Judd, “Reinterpreting Al-Walīd b. Yazīd” in Journal of American Oriental Society 128, no. 3 (2008): 439-441.

[9] Bacharach, “Marwainid Umayyad Building Activites: Speculations on Patronage” in Muqarnas 13 (1996): 37.

[10] Ballain, “Country Estates, Material Culture, and the Celebration of Princely Life: Islamic Art and the Secular Domain,” 203.

Bibliography:

Bacharach, Jere L. “Marwanid Umayyad Building Activities: Speculations on Patronage.”

Muqarnas 13 (1996): 27–44. https://doi.org/10.2307/1523250.

Ballian, Anna. “Country Estates, Material Culture, and the Celebration of Princely Life: Islamic

Art and the Secular Domain.” In Byzantium and Islam: Age of Transition, 7-9th Century,

edited by Helen C. Evans and Brandie Ratliff, 200-208. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art,

2012.

Birk, Stine, Kristensen Myrup Troels, and Birte Poulsen. Using Images in Late Antiquity. Oxford: Oxbow

Books, 2014. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvh1dwzx.

Ettinghausen, Richard, Oleg Grabar, and Marilyn Jenkins-Madina. Islamic Art and Architecture

650-1250. New Haven: Yale University Press , 2001.

Grabar, Oleg. “The Date and Meaning of Mshatta.” Dumbarton Oaks Papers 41 (1987): 243–47.

https://doi.org/10.2307/1291562.

Judd, Steven. “Reinterpreting Al-Walīd b. Yazīd.” Journal of the American Oriental Society 128,

no. 3 (2008): 439–58. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25608405.

Townson, Alexander. “Mshatta’s Façade and the Viewer.” In Made for the Eye of One Who

Sees: Canadian Contributions to the Study of Islamic Art and Archaeology, edited by

Marcus Milwright and Evanthia Baboula, 25–54. Montreal, Quebec: McGill's Univesity Press, 2022.