Mia Sedory - The Blue Qur'an: Catalogue Entry

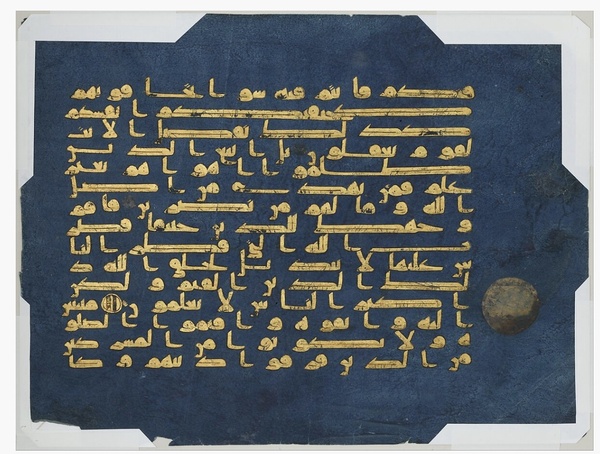

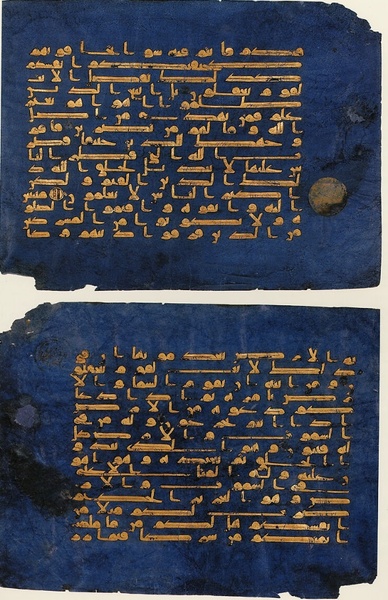

The Blue Qur’an “is one of the most memorable and celebrated works for Islamic art.”[1] It is not only a work of art, but also an exemplar of beauty and extravagance. With its 650 folios of richly colored indigo parchments and gold leaf calligraphy this manuscript, dated at late ninth to early tenth century, stands out among the other Qur’anic manuscripts and shines bright as an integral artifact of Islamic culture.[2] Despite being such a famous manuscript, there are very few elements of the Blue Qur’an’s history that are known with certainty.

Many disagree about multiple aspects and information regarding the Blue Qur’an. Currently, even the region of production is uncertain. George Alain analyzes the manuscript’s color and calligraphy, and through that analysis concludes that the manuscript could have been made in Baghdad.[3] Meanwhile, D’Ottone Rambach argues that since the Blue Qur’an is connected to the Bible of Cava, the production is attributed to 9th-centrury Spain, where the Bible was known.[4] The Metropolitan Museum of Art attributes the Blue Qur’an to North Africa, specifically Tunisia.[5] However, Jonathon Bloom argues that “the long presence of the manuscript in Tunisia is certainly not evidence that it was made there.”[6] Bloom’s hypothesized region of origin to includes all of North Africa.[7]

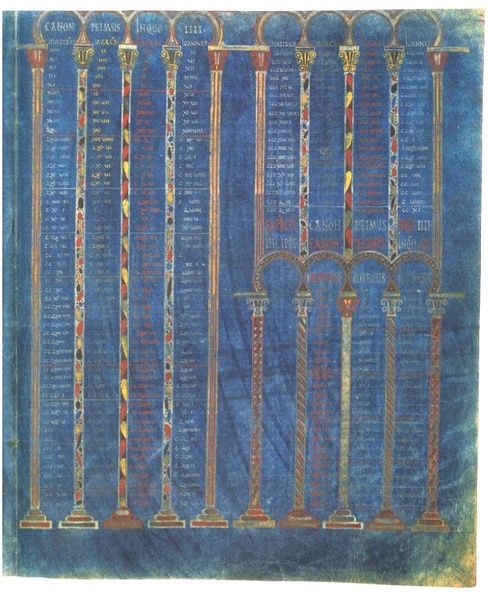

One possible way into gain insight on the region of production is to investigate potential patrons. Bloom states that while some scholars believe the Aghlabids were the patrons, this was unlikely. He argues that it was the Fatimids who were the patrons.[8] It is his opinion that the blue and gold color scheme was inspired by Byzantine manuscripts, and it was the Fatimids who had diplomatic relations with the Byzantines.[9] D’Ottone Rambach hypothesizes that the manuscript was commissioned by an Umayyad patron in Spain. The similarities between the Bible of Cava (specifically in the color of the parchments and the ruling) hint to the two influencing each other, and subsequently leading to implications that the person who commissioned the Blue Qur’an was aware of the Bible of Cava (as seen in figure 3) and aimed to create their own manuscript that would rival it.[10] Unfortunately there has not been a consensus between scholars regarding the region of origin or patronage of the Blue Qur’an.

However, despite all the controversy regarding the origins of the Blue Qur’an, it is clear that Blue Qur’an is truly opulent. This manuscript’s luxurious indigo color signals its monetary value as well as its prestige. Further, its gold leaf calligraphy demonstrates both the financial and labor-intensive investment into the manuscript. Additionally, due to the larger size of the Blue Qur’an – thirty-one by forty-one centimeters – one sheepskin would have only been able to make two bifolia.[11] (A bifolio is four folios or eight pages.[12]) This means that the Blue Qur’an required at least 150 animals.[13] The myriad of resources and the accumulation of them, attests to the opulence of the manuscript.

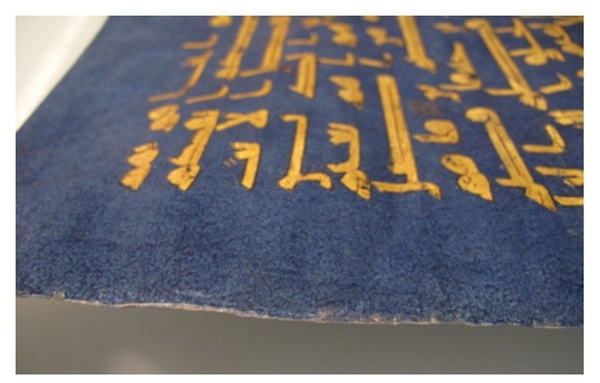

Furthermore, the long, difficult process of making the Blue Qur’an and the precision and meticulousness required for it affirm the manuscript’s grandeur. The process begins with turning the sheep skin into parchment. Skins from adult sheep and goats were thinner than that of calves, and thus made for better parchment.[14] Skins were soaked for several days in a lime solution.[15] Then the hair was scraped off before and during the time in which the skin was stretched out on a frame.[16] During the second scraping the skin was also rubbed with pumice to make it more susceptible to the ink.[17] If the skin was still greasy after it had dried it was treated with lime, chalk, or wood ash (which were applied as wet pastes or dry powders).[18]

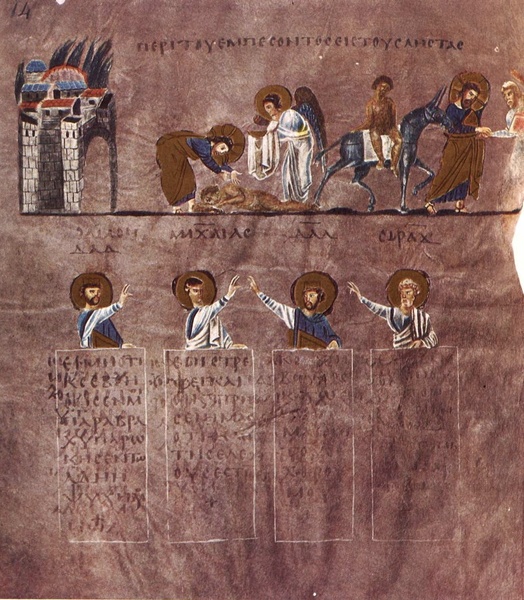

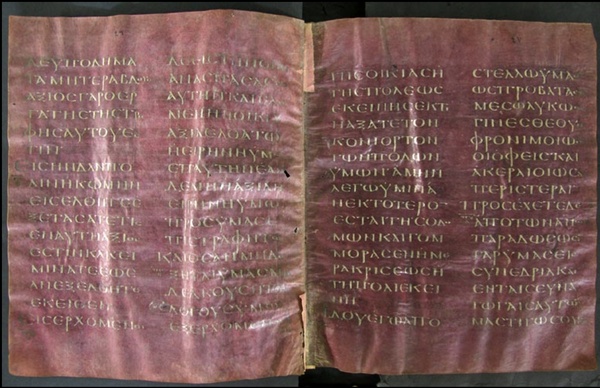

After the skin was processed, it had to be colored. While the Blue Qur’an was unique in some regards, the fact that the manuscript is colored is not. The Blue Qur’an is one of many colored manuscripts. One of the oldest examples of a manuscript that has a similar shade to the Blue Qur’an is the Codex Rossanensis which is known for its purple coloring (as seen in figure 4). Scholars thought that Tyrian was used to dye the parchment but there is no evidence for this.[19] Another manuscript known for its purple shade is the Greek manuscript Purpureus Petropolitanus (as seen in figure 5 ).[20] The Codex Rossanensis and the Purpureus Petropolitanus were both produced at least two centuries before the Blue Qur’an which shows that the process of coloring manuscripts a blue or purple color began long before the Blue Qur’an.[21]

While the Blue Qur’an’s color may not be novel, it is nonetheless striking. The famous blue color comes from an indigotin-bearing plant (either woad, which is the European - North African indigo plant, or Indian indigo called nil) and it produces a rich dark blue shade.[22] To investigate the methods of how the famous indigo-blue color was added to the parchment, Cheryl Porter conducted an experiment where she painted one sheep parchment and dyed the other. She learned that both painting and dyeing are plausible possible processes.[23] Emily Neumeier affirms that the process for which the Qur’an was colored remains unknown.[24] While it is not clear which plant was used for the dye, or what the dyeing process was, scholars have at least found potential answers.

Following the parchment making process, the parchment is ruled out using various lines to create a baseline layout for the artist.[25] The calligraphers then “write” with gold leaf.[26] The technique for this consists of marking out the words with a pen, brush or reed covered in adhesive (often a gum, egg white mixture, or animal protein adhesive), laying the gold leaf onto the area with the adhesive script, and then using cloth to “damp it into position.”[27] After the adhesive dries the excess gold is brushed away and the text, now covered in gold, remains.[28] When this entire process was finished, the magnificent Blue Qur’an was completed. Part of what makes the Blue Qur’an so impressive is how arduous and intricate the production for it was. Everything luxurious requires effort, and the more labor and time that goes into something, the more valuable it is. The combination of the expensive materials and the labor-intensive, time-consuming process is what makes the Blue Qur’an so beautiful and extravagant.

However, everything beautiful comes with a cost. Or rather, in this case, beautiful things have such value that they are vulnerable to others’ immorality. The Blue Qur’an has unethically been damaged, divided, and sold for profit. The last time the Blue Qur’an was reported to be in one piece was in 1293.[29] At one point the manuscript was split into seven parts and the first part was separated from the manuscript.[30] Most of the western collections of the manuscript from the early twentieth century begin before verse 4:55, which is approximately where the first of seven sections should have ended.[31] The other six sections are possibly in Kairouan, but Tunisian officials have not allowed western scholars to inspect their Blue Qur’an manuscript leaves.[32] Some scholars hypothesize that the division began in the sixteenth century after the Ottomans captured Tunisia while others argue that there is not enough evidence to back that claim.[33] Either way, all scholars agree that they do not know why the Blue Qur’an was broken up.[34]

After 1293, the Blue Qur’an had no trace until Fredrik Martin.[35] Martin acquired several leaves before selling it to the Museum of Fine Arts, the Seattle Art Museum, the Fogg Art Museum, Sir Alfred Chester Beatty, and Prince Sadruddin Aga Khan.[36] The value of these pages started at today’s equivalent of $1,400 in 1933.[37] .[38] In 2010, Martin’s leaves sold for $835,000.[39]

Martin was not the only holder of these leaves. In 1986, 18 folios of the Blue Qur’an had been counted across private and museum collections.[40] By 2005, 37 separate folios have been counted.[41] In 2009 around 100 leaves of the manuscript are divided among public and private collections all over the world.[42] The international market for manuscripts is what leads to the breakup of these precious manuscripts. This is where questions around ethicality regarding preservation and profit come in. Is it ethical to divide such an important artifact from Islamic culture? If the Ottomans were the ones to divide the manuscript, was it ethical for them to destroy the bindings of the Blue Qur’an to split it up? Since they conquered Tunisia, does that give them the right to damage and divide the manuscript, or do they have the responsibility as the people in power to preserve it? Even if it was not the Ottomans who divided the manuscript, the question remains: who has the authority to divide such an integral piece of Islamic culture? Is it moral for anybody to divide the Blue Qur’an?

Another debate around ethicality lies in the current art market. The issue is that the inflation within art market has led to private museums and private collectors holding a large enough portion of the purchasing power that many public institutions have been pushed out of the market, especially when it comes to artifacts as famous as the Blue Qur’an. [43] Should public museums be the institutions that hold the Blue Qur’an’s folios, or should the folios be sold to private museums and collectors? Who has the authority to hold the Blue Qur’an? These are all questions to ponder when discussing this extravagant manuscript.

The Blue Qur’an brings with it many controversies: its unknown history, its unclear production methods, its division, and its rightful owner. It seems there are more questions regarding the Blue Qur’an than there are answers. However, one thing is for certain – the Blue Qur’an is truly luxurious. Yet that leads to one last another question – was it the Blue Qur’an’s extravagance that eventually led it to its own damage and division, and if so, does extravagance in art inherently endanger the art itself?

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

[1] Carboni Stafano, Navina Haidar, and Maryam Ektihar, “Islam,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 62, no. 2 (2004): 10, https://doi.org/10.2307/20061937.

[2] Emily Neumeier, “Early Koranic Manuscripts: The Blue Koran Debate,” Elements 2, no. 1 (2006): 12. https://doi.org/10.6017/eurj.v2i1.8938 and Stafano Carboni, Haidar Navina, and Ektihar Maryam, “Islam,” 10.

[3] Alain George, “Calligraphy, Colour and Light in the Blue Qur’an,” Journal of Qur’anic Studies 11, no. 1 (2009):108, https://doi.org/10.3366/E146535910900059X

[4] Arianna D’Ottone Rambach, "The Blue Koran,” A Contribution to the Debate on Its Possible Origin and Date." Journal of Islamic Manuscripts 8, 2 (2017): 139, https://doi.org/10.1163/1878464X-00801004c.

[5] Stafano Carboni, Haidar Navina, and Ektihar Maryam, “Islam,” 10.

[6] Jonathan M. Bloom, "The Blue Koran Revisited,” Journal of Islamic Manuscripts 6, 2-3 (2015): 206, doi: https://doi.org/10.1163/1878464X-00602005

[7] Jonathan M. Bloom, "The Blue Koran Revisited,” 206.

[8] Jonathan M. Bloom, "The Blue Koran Revisited,” 200.

[9] Jonathan M. Bloom, "The Blue Koran Revisited,” 200.

[10] Arianna D’Ottone Rambach, "The Blue Koran,” 138.

[11] Susan Whitfield, “The Blue Qur’an,” in Silk, Slaves, and Stupas: Material Culture of the Silk Road, (Oakland: University of California Press, 2018.), 171.

[12] Whitfield, “The Blue Qur’an,” 171.

[13] Whitfield, “The Blue Qur’an,” 171.

[14] Whitfield, “The Blue Qur’an,” 171.

[15] Whitfield, “The Blue Qur’an,” 171.

[16] Whitfield, “The Blue Qur’an,” 171.

[17] Whitfield, “The Blue Qur’an,” 171.

[18]Whitfield, “The Blue Qur’an,” 171.

[19] Bicchieri, 14156 https://rdcu.be/da5Dr

[20] Whitfield, “The Blue Qur’an,” 175.

[21] Whitfield, “The Blue Qur’an,” 175. and Bicchieri 14156 https://rdcu.be/da5Dr

[22] Cheryl Porter, “The Materiality of the Blue Quran: A Physical and Technological Study.” In The Aghlabids and Their Neighbors, (The Netherlands: Brill, 2017) 577.

[23] Porter, “The Materiality of the Blue Quran,”579.

[24] Neumeier, “Early Koranic Manuscripts,”17.

[25] Neumeier, “Early Koranic Manuscripts,”17.

[26] Cheryl Porter, “The Use of Metals in Islamic Manuscripts.” In The Making of Islamic Art: Studies in Honour of Sheila Blair and Jonathan Bloom edited by Robert Hillenbrand, (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2021) 261.

[27] Porter, “The Use of Metals in Islamic Manuscripts,”261.

[28] Porter, “The Use of Metals in Islamic Manuscripts,”261.

[29] Neumeier, “Early Koranic Manuscripts,”16.

[30] Neumeier, “Early Koranic Manuscripts,”16.

[31] Neumeier, “Early Koranic Manuscripts,”16.

[32] Neumeier, “Early Koranic Manuscripts,”16.

[33] Whitfield, “The Blue Qur’an,” 184.

[34] Whitfield, “The Blue Qur’an,”187.

[35] Neumeier, “Early Koranic Manuscripts,”16.

[36] Jonathan M. Bloom, "The Blue Koran Revisited,” 204.

[37] Jonathan M. Bloom, "The Blue Koran Revisited,” 204.

[38] Jonathan M. Bloom, "The Blue Koran Revisited,” 199.

[39] Jonathan M. Bloom, "The Blue Koran Revisited,” 204.

[40] Neumeier, “Early Koranic Manuscripts,”16.

[41] Neumeier, “Early Koranic Manuscripts,”16.

[42] Neumeier, “Early Koranic Manuscripts,”16.

[43] Whitfield, “The Blue Qur’an,” 188.

Bibliography

Bicchieri, Marina. “The Purple Codex Rossanensis: Spectroscopic Sharacterisation and First Evidence of the Use of the Elderberry Lake in a Sixth Century Manuscript.” Environmental Science and Pollution Research 21 (2014):14146–14157 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-014-3341-6

Bloom, Jonathan M. "The Blue Koran Revisited." Journal of Islamic Manuscripts 6, 2-3 (2015): 196-218. https://doi.org/10.1163/1878464X-00602005

Carboni Stafano, Haidar Navina, and Ektihar Maryam. “Islam.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 62, no. 2 (2004): 10–11. https://doi.org/10.2307/20061937.

D’Ottone Rambach, Arianna. "The Blue Koran.” A Contribution to the Debate on Its Possible Origin and Date." Journal of Islamic Manuscripts 8, 2 (2017): 127-143. https://doi.org/10.1163/1878464X-00801004c

George, Alain. “Calligraphy, Colour and Light in the Blue Qur’an.” Journal of Qur’anic Studies 11, no. 1 (2009): 75–125. https://doi.org/10.3366/E146535910900059X

Neumeier, Emily. 2006. “Early Koranic Manuscripts: The Blue Koran Debate.” Elements 2, no. 1 (2006):10-19. https://doi.org/10.6017/eurj.v2i1.8938.

Porter, Cheryl. “The Use of Metals in Islamic Manuscripts.” In The Making of Islamic Art: Studies in Honour of Sheila Blair and Jonathan Bloom edited by Robert Hillenbrand, 260–79. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2021.

Porter, Cheryl. “The Materiality of the Blue Quran: A Physical and Technological Study.” In The Aghlabids and Their Neighbors 573–586. The Netherlands: Brill, 2017

Whitfield, Susan. “The Blue Qurʾan.” In Silk, Slaves, and Stupas: Material Culture of the Silk Road, 1st ed, 164–89. Oakland: University of California Press , 2018.