The Great Mosque of Isfahan - Catalog Entry

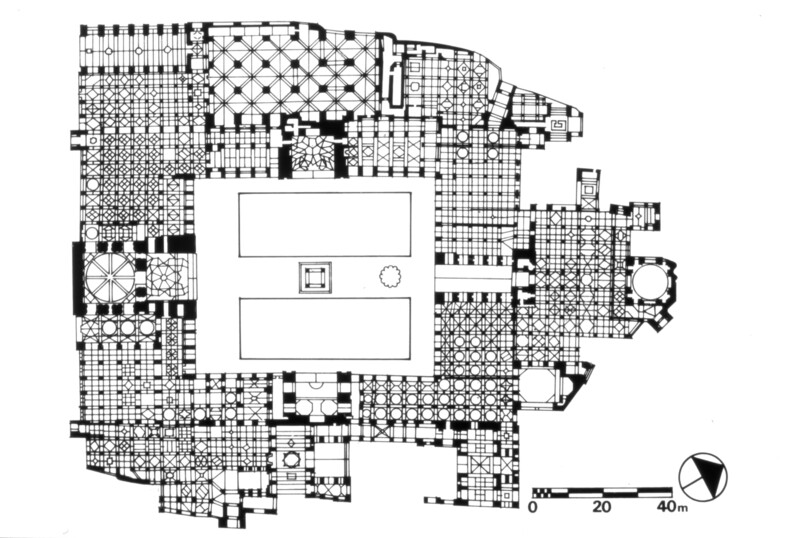

The Masjid-e Jameh, also known as the Friday Mosque of Isfahan or the Great Mosque of Isfahan, is an incredibly unique Mosque that transcends eras in material, architectural features, and ornamentation. With an original size of 88x128 meters, over one thousand years of additions have expanded the structure to a massive 170x140 meters[1]. The Great Mosque of Isfahan contains a courtyard bordered by four iwans, of which the north and south lead to two dome rooms. The Great Mosque of Isfahan contains four minarets, several rectangular cross-ribbed halls, an attached madrassa, and several extended prayer halls. The Great Mosque of Isfahan is constructed using a variety of building materials, from baked brick, stucco, and originally wood to elaborate tilework and colored bricks which covers the iwans and minarets[2]. The mosque contains several inscriptions, tile facades, and ornamental brickwork masterpieces, definitions of their contributors’ impact on the Masjid-e Jameh. These aspects combine to form a Great Mosque of Isfahan shaped through the years by several dynasties, each leaving its marks with expansions, ornamentations, and purpose.

Built atop a prior small mud-brick Mosque which originated around 771 CE[3], the Masjid-e Jameh was initially constructed in 840-841 as a hypostyle mosque with a seemingly abnormally placed minaret and an inbuilt North-South axis. Over the years, it was modified in minor ways until 985-1040, in which the Buyids retrofitted the courtyard and interior spaces, added natural expansions (duwar), and constructed two additional minarets. From 1051-1118 Isfahan became the de-facto capital of the Seljuq Turks, giving rise to some of the most significant changes to the Great Mosque’s structural elements. In 1086-1087 the south dome was constructed, followed by the north dome in 1088, creating focal points for the mosque where there previously were none. These additions are uniquely Seljuk with iconic brickwork and matching inscriptions praising the Seljuk Sultan. Throughout the 1100s, a variety of additions were made, including the addition of a fourth minaret, the modification of much of the hypostyle halls into domed halls, and after a fire in 1121, the addition of the iconic four Iwans to the courtyard to connect the dome rooms and courtyard in theme [4]. After these changes, the Great Mosque of Isfahan changed hands several times, with additions happening under the Timurids, Muzaffarids, and Safavids, who expanded the mosque and added the distinct blue tilework which covers the minarets and iwans. While several portions of the Great Mosque of Isfahan have come into disrepair, modern restoration has recovered some aspects starting in the mid-1700s[5].

While originating as an Islamic center of influence for its area, the Great Mosque of Isfahan became whatever the dynasty that inhabited the city needed it to be. In 771, the earlier mosque, built from mud brick and stucco, was used as the mosque of Islamic authority in the region, as evidenced by the transfer of a minbar from another previous mosque in the area and the addition of a maqsurah (a fancy enclose used to house people of authority). While maintaining some of the original significance of a cultural center, the destruction and rebuilding of the Masjid-e Jameh gave rise to a new use established by the Buyids. The Great Mosque of Isfahan, while still a monument to Islamic authority, was used as a political, social, or even educational space with a refurbished interior and duwar. The Seljuks changed this meaning once again, but this time in a more obvious way. With the direct intervention by Sultan Malkishah and his vizier, the addition of the north and south domes made the mosque into a monument to the greatness and architectural mastery of the Seljuks. From the dome’s mathematical perfection, satisfying the mathematician and everyday worshiper[6], to the inscription on the south dome, singing praise to the Seljuk Sultan[7], the Great Mosque of Isfahan became an object of grandeur. By the time of the Timurids and Muzaffids, the Great Mosque of Isfahan was, in essence, a prayer space but also a monument and multifunctional building laden with architectural marvels of impressive scale. The purpose of the mosque persisted with upkeep and the consistent addition of new structures and modification of old structures for new design elements such as the iwans, blue tilework, and further duwar. The Great Mosque of Isfahan originated as a prayer space and cultural center. However, over the centuries gained significance as a multifaceted and monumental building as the mosque expanded.

The Great Mosque of Isfahan has few known makers but dynasties who retrofitted the mosque. The Buyids (985-1040) stand out in revamping the interiors of the Great Mosque of Isfahan as the first significant dynasty to control the city. In their construction of educational and religious additions, not many viziers’ names are known besides Ala al-Dawlah Muhammed b. Dushmanziyar, who ruled as governor over Isfahan for nearly forty years[8]. The most apparent of these makers are the Seljuk Turks (1050-1118) under Sultan Malik-Shah I. Nizam al-Mulk, a vizier of the Sultan, oversaw the construction of the south dome, one of the largest domes in the Islamic world, in 1086-1087[9]. The following year, Nizam al-Mulk’s rival Taj al-Mulk sponsored the north dome, a perhaps even greater dome thought to be attributed to the great mathematician Omar Khayyam[10]. These domes stand as a testament to the power and elegance of the Seljuk dynasty in style and name especially the north dome being renowned for its peerless design and innovation in ornamental brickwork[11]. The Seljuks also left many inscriptions within the mosque, marking their involvement and faith in the several Qur’anic inscriptions. Importantly both domes praise Malik-Shah I and their respective sponsors, giving names and dates to the makers of two defining features of the mosque[12]. Another dynasty that claimed themselves makers were the Muzaffarids, who ruled Isfahan between 1314-1393. Over this period, many changes were made to the façade of the building, with distinct colored bricks and tiles added as ornamentation. An elaborate mihrab memorializes this period made in 1310 under the order of Oljaytu, the first Mongol ruler of the city, marking a claim to the expansions made to the mosque under the Muzaffarids[13]. While not every name is known, the many who constructed the Great Mosque of Isfahan differ significantly in intention, each contributing components to the unique and massive whole of the mosque.

One of the most impressive aspects of the Great Mosque of Isfahan is its scale. The Masjid-e Jameh deserves the title of a Great Mosque due to its sheer size and the significance of the domes and iwans. The Great Mosque of Isfahan spans a massive 170 by 140 meters[14], beating out the Great Mosques of Damascus and Cordoba in sheer scale. In the over one thousand years of the lifespan of the Great Mosque of Isfahan, the building has grown significantly owed in full to the many dynasties that claimed it as their own. The mosque has received many additions, ranging from the smallest duwar to the addition of its signature domes and iwans. Built by the Seljuks, the northern dome room is 39 meters tall. It is a masterwork in brickwork only matched by the southern dome in intricacy[15]. While not wholly attributed to one dynasty, the four iwans are each 27 meters high and gilded with immaculate tilework, expanding upon the impressive mosque. The grandeur in the scale of the building is not only apparent but a defining aspect of the Masjid-e Jameh. Each dynasty that claimed the Great Mosque of Isfahan contributed not only towards the size of the mosque but towards the rich history and longevity of the building. Today the Great Mosque of Isfahan remains a celebrated cultural monument to the city’s history. The mosque has withstood the ages and continues to be restored to this day to preserve the immense scale of the Great Mosque of Isfahan.

The Great Mosque of Isfahan fits under the theme of extravagance because of its scale and purpose. The scale of the mosque is extravagant in that the building spans a massive distance. With four tiled iwans, two immaculately constructed domes, and four minarets, the sheer amount of architectural feats defines the Great Mosque. The sheer scale of the building as the cumulation of over a thousand years of work is by nature extravagant. While not originally planned to be a mosque of great size, the eventual growth of the Masjid-e Jameh lends it a mythical quality as each expansion is unique to an era or dynasty. The Great Mosque of Isfahan has a significant amount of inbuilt cultural experience. To the original creators, it was a center of Islamic influence, but over time, the Masjid-e Jameh gained extravagance through its versatility. The Buyids characterized the Great Mosque of Isfahan as a sacred space of educational and societal importance. The Seljuk Turks made the mosque into an object of grandeur with legendary domes to match. Every dynasty after aided not only in the construction of the Great Mosque of Isfahan but towards the extravagance of the multicultural and multifunctional nature of the structure. While not originally as extravagant as other mosques at the time, the accumulation of scale and purpose has defined the Great Mosque of Isfahan as a feat in mosque architecture.

[1] Massumeh Farhad and Eugenio Galdieri, “Friday Mosque [Masjid-i jum’a] (Isfahan),” Grove Art Online, Accessed March 26, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1093/oao/9781884446054.013.90000369839.

[2] Oleg Grabar, The Great Mosque of Isfahan (New York: New York University Press, 1990), 61-68.

[3] Eugenio Galdieri, “The Masğid-i Ğum῾a Isfahan: An Architectural Façade of the 3rd Century H,” Art and Archaeology Research Papers 6 (1974): 24–34.

[4] Grabar, The Great Mosque of Isfahan, 55-57.

[5] Massumeh, Galdieri, “Friday Mosque.”

[6] Alpay Özdural, “A Mathematical Sonata for Architecture: Omar Khayyam and the Friday Mosque of Isfahan,” Technology and Culture 39, no. 4 (1998): 699–700, https://doi.org/10.2307/1215845.

[7] Sheila Blair, The Monumental Inscriptions from Early Islamic Iran and Transoxiana, (Leiden; Boston: E.J. Brill, 1992), 164-167.

[8] Grabar, The Great Mosque of Isfahan, 47.

[9] Grabar, The Great Mosque of Isfahan, 49.

[10] Özdural, “A Mathematical Sonata,” 711-714.

[11] Jay Francis Bonner, “The Historical Significance of the Geometric Designs in the Northeast Dome Chamber of the Friday Mosque at Isfahan,” Nexus Network Journal 18, no. 1 (2016): 60-62.

[12] Blair, The Monumental Inscriptions, 164-167.

Works Cited

Blair, Sheila. The Monumental Inscriptions from Early Islamic Iran and Transoxiana. Leiden ; Boston: E.J. Brill, 1992.

Bonner, Jay Francis. “The Historical Significance of the Geometric Designs in the Northeast Dome Chamber of the Friday Mosque at Isfahan.” Nexus Network Journal 18, no. 1 (2016): 55–103.

Farhad, Massumeh and Eugenio Galdieri. “Friday Mosque [Masjid-i jum‛a] (Isfahan).” Grove Art Online. Accessed March 26, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1093/oao/9781884446054.013.90000369839.

Galdieri, Eugenio. “The Masğid-i Ğum῾a Isfahan: An Architectural Façade of the 3rd Century H.” Art and Archaeology Research Papers 6 (1974): 24–34.

Grabar, Oleg. The Great Mosque of Isfahan. New York: New York University Press, 1990.

Özdural, Alpay. “A Mathematical Sonata for Architecture: Omar Khayyam and the Friday Mosque of Isfahan.” Technology and Culture 39, no. 4 (1998): 699–715. https://doi.org/10.2307/1215845.