Tile from the Chashma-i Ayub Portal Frame - Catalogue Entry

What is the Chashma-i Ayub Tile?

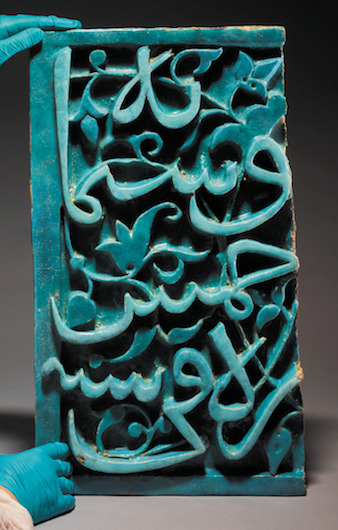

The Chashma-I Ayub Tile is a decorative, turquoise-glazed tile fragment of elaborate Arabic calligraphic writing. The tile is 52.5cm high and 30.5cm across. [1] It is part of a larger epigraphic band made of sculpted baked clay covered in an opaque turquoise glaze, which adorns the top of the external entrance portal of the Chashma-i Ayub Mausoleum complex. [2] The rest of the epigraphic band has the same turquoise coloration and calligraphic style as this tile section. When translated, the full band reads “The Prophet - peace be upon him - said: I had forbidden you to make pilgrimages to tombs. Now make pilgrimages. This monument was erected in the year five and six hundred.” [3] The here discussed tile fragment is the final section of the band and contains the dates at the end of the inscription. [4] The Chashma-i Ayub complex is located a few kilometers away from Vabkent, in the Bukhara region of Uzbekistan. The hazira, the wall surrounding the complex, is almost entirely destroyed, with only the entrance portal and a small portion of the adjacent wall remaining. [5] Besides the inscription band made of tile, the portal features carved stucco sections, vegetal ornamentation, a pointed vase shaped capital, and honeycomb-like decorative bands. [6]

When was the Chashma-i Ayub Tile made?

The Chashma-i Ayub tile can be easily dated by its inscription. The inscription refers to the year “five and six hundred” meaning AH 605 in the Muslim calendar, or 1208/1209 C.E. [7] The complex’s central Asian location and construction period identify the tile within the final years of the Qarakhanid dynasty, which ruled in the eleventh and twelfth centuries, ending in 1212 C.E. [8]

Where was the Chashma-i Ayub Tile produced, and where did it go?

The exact production place of the Chashma-i Ayub tile is unknown, nor are there any identification markers that could pinpoint a creator. However, given the content of the inscription, [9] the tile was almost certainly created for the purpose of adorning the entrance portal of the Chashma-i Ayub complex. In 2014, the tile was illegally removed from the portal façade by an unknown thief. [10] The tile was trafficked to Europe and offered for sale in 2016 [11] by Simon Ray, a prominent London art dealer. Ray had originally bought the artifact in good faith and was unaware that it was stolen. [12] Upon learning the tile’s illegal origin, Ray brought the object to the British Museum, which then handed the tile over to the Uzbeki government. [13] The tile is now in the Kurbanshaid Museum in Tashkent, with plans to restore it to the Chashma-i Ayub portal façade. [14] Although the decorations of the façade had been undisturbed by historical looting or repurposing, present-day thievery has resulted in the circulation of this tile.

Why was it made, and how was it used?

The Chashma-i Ayub complex serves numerous purposes such as a religious monument, site of pilgrimage, and mausoleum. The complex is meant to mark a place visited by Ayyub, also known by the Christian name Job. [15] In Koranic tradition, Iblis cursed the prophet Ayyub with disease to test his faith, and he was only granted relief when God created a healing spring of water. [16] In Central Asian folklore, Ayyub was also seen as a healer and a patron of silk farming. [17] Ayyub played the role of an “exemplarily” Muslim in Koranic tradition [18] which, coupled with his regional economic importance, made him an important figure to the Bukhara region. As a result, numerous monuments in the region were dedicated to him. [19] The name of the Chashma-i Ayub complex clearly identifies its connection to the prophet. Furthermore, the fountain within the mausoleum itself [20] acts as a reference to the healing spring in the story. Finally, the bright turquoise tile color was associated with health and cured infertility and sterility, [21] connecting the Chashma-i Ayub complex and its turquoise tilework with the healing of Ayyub.

The inscription on the tile band reveals another factor involved in building the complex. The inscription is the final part of a hadith, which scholar al-Ghazali quotes in support of ziyara, the pilgrimage to sites associated with venerated Islamic figures. [22] Debate existed in Muslim society about whether visiting shrines was idolatry, [23] so the use of the quote illustrates a Qarakhanid defense for building monuments like the Chashma-i Ayub mausoleum. An additional facet to the complex and entrance portal’s purpose was its use in later centuries. Although the complex originally marked Ayyub’s visit, it was rebuilt numerous times by Timur rulers in later centuries, who also used it as a burial site. [24] So while the decorative aspects of the tile still played a similar role under Timur rulers, their context shifted to being the entrance to a mausoleum instead of a just a monument.

How does the Chashma-i Ayub tile relate to the moral implications of extravagance?

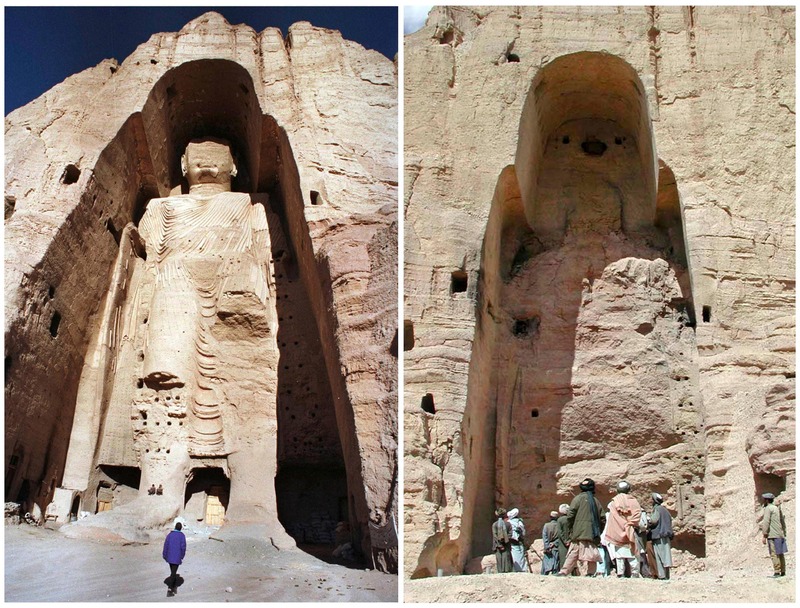

The Chashma-i Ayub tile piece plays not just a historical role in decorating the complex's portal, but today its changing whereabouts also illustrate the moral concerns of modern art theft and sale. One form of art theft, “theft by destruction”, refers to the extirpation of art or cultural objects beyond the point of recovery. [25] The ‘theft’ refers to the idea that the object has been functionally stolen from a culture, with no hope of recovery since it no longer exists. This tactic has long been used by combatants in wars and by terrorist organizations. Recently Islamic terrorist groups have attacked and destroyed art from opposing Islamic branches and from other religions. For example, in 2001 the Taliban destroyed 1,800-year old Buddha statues in Bamiyan, Afghanistan. [26] Fortunately, the complete destruction of art was not a factor in the theft of the Chasma-i Ayub tile, although the cohesion of the complex’s decoration was impaired through the theft, degrading the artistry as a whole. Here the form of art theft involved the removal of art form its origin but not its extirpation.

The moral implications of art theft extend beyond the artifact itself. Art represents a country or people's culture and history, and UNESCO holds that sustainably safeguarding art and artifacts is critical for maintaining a nation’s cultural heritage. [27] As such, art theft not only robs a nation of a material object, but also robs them of an aspect of their history and culture. Protecting art from theft therefore carries the moral weight of protecting the culture and history of the people to whom the art belongs. For the Chashma-i Ayub tile, its theft represents the theft of a part of Uzbeki culture and history. Fortunately, the tile was well documented before its theft, and its return has restored the history the tile contains. However, if that had not occurred, as is the case for many other art pieces, the injustice of the theft would’ve been permanent.

Finally, art theft carries moral implications because of the financial profit the sale of stolen art produces. The sale of stolen art enriches art thieves. This is especially problematic in recent decades, as terrorist groups such as ISIL [28] and Al Qaeda use the sale of stolen Islamic art to help fund their activities. [29] Art theft has contributed to other illegal and unethical activities, creating additional moral consequences. The perpetrator behind the Chashma-i Ayub tile’s theft is unknown, however, their successful sale of the tile may have been used to fund further illicit activities, and at the very least, rewarded the thief with a monetary benefit.

The sale of stolen art creates then a moral conundrum forthe unaware buyer. An unaware buyer who realizes they’re in possession of a stolen artifact must balance the moral imperative to return stolen artifacts with the financial loss they would experience from that return. They too have been treated unjustly by the art thief who tricked them. The moral difficulty of this situation has prompted museums to establish ethical guidelines that prohibit them from buying artifacts with even slightly suspicious origins. [30] Simon Ray, the buyer of the Chashma-i Ayub tile who was unaware of the tile’s origin [31] faced the moral conundrum of weighing the moral wrong of the theft against his financial loss were he to return the stolen goods. Ray’s ultimate decision to report the theft and handover the tile to the British Museum corrected the moral wrong of the theft, but nonetheless the action failed to rectify the wrong of having been tricked into buying it.

How does the Chashma-i Ayub Tile relate to extravagance?

The Chashma-i Ayub tile possesses numerous characteristics of extravagance. Perhaps the most notable facet of the tile is its bold turquoise color. In Central Asian Islamic tradition, turquoise was a color associated with holiness, with connections to health, growth, and the preeminence of light over darkness. [32] The brilliant turquoise carried additional weight on the steppes, where it was used to “accentuate and enliven architectural forms, notably by imitating the sky’s color”. [33] The color of the tile was highly fashionable at the time, [34] demonstrating the extravagance, wealth, and artistry of the rulers that built it, and distinguishing the Chashma-i Ayub complex from surrounding buildings. The highly defined calligraphy also functions within discourses of extravagance. The epigraphy correlates with a rising concern over legibility, requiring experimentation with techniques imported from Iran. [35]

The connection of the color and epigraphic style to extravagance is further manifested by the prominence of these characteristics in important buildings around the region. The Namazgah Mosque in Bukhara is decorated with a similar turquoise calligraphic frieze to the right of the qibla wall. [36] Additonally, these characteristics feature prominently on one of the most extravagant buildings in the region, the Shah-e Zende Necropolis in Samarkand. The grand facades display bright turquoise tiles and calligraphic script, matching that of the Chashma-i Ayub complex. [37] The repetition of certain characteristics across religious architectural edifices like the Chashma-i Ayub portal, Namazgah Mosque, and Shah-e Zende Necropolis indicate that these characteristics are meant as displays of extravagance and value.

However, the extravagance of artifacts like the Chashma-i Ayub tile has consequences for its safety from thieves today. Beautiful and rare as these pieces are, Western demand for Islamic art has increased in the past few decades, [38] with many buyers for stolen Islamic art living in the United States or Europe. [39] The extravagance of Islamic art pieces makes them not just desirable but also increases the perceived value of the objects, creating increased risk of and police concern for theft. [40] The brilliant color and detailed calligraphic inscription of the Chashma-i Ayub tile no doubt made it a target for art theft. Ultimately, the extravagance of Islamic art is a fundamental part of its beauty and cultural significance, but in the modern day it also makes those artifacts ripe for theft, and all the moral implications that follow.

Endnotes

1. Dalya Alberge, “British Museum helps return stolen artefact to Uzbekistan,” The Guardian, 17 July 2017, Accessed 2 April 2023, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/jul/17/british-museum-helps-return-stolen-artefact-to-uzbekistan.

2. Jean Soustiel and Yves Porter, Tombs of Paradise: The Shah-e Zende in Samarkand and Architectural Ceramics of Central Asia (Saint-Rémy-en-l'Eau: Monelle Hayot, 2003), 34-35.

3. St. John Simpson, “From Seizure or Donation of Antiquities to Their Identification and Research at the British Museum and Repatriation to the Countries of Origin: Recent Case Studies from Afghanistan, Uzbekistan and Iraq,” Journal of Art Crime 24 (Fall 2020): 12.

4. Richard Piran McClary, Medieval Monuments of Central Asia: Qarakhanid Architecture of the 11th and 12th Centuries (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2020), 141.

5. Soustiel and Porter, 34.

6. McClary, 141-143.

7. Simpson, 121.

8. McClary, 2.

9. Simpson, 121.

10. Simpson, 121.

11. McClary, 140.

12. Alberge.

13. Simpson, 121.

14. McClary, 141.

15. Soustiel and Porter, 34.

16. Barbara B. Pemberton, “Job: Servant of Yahweh/Prophet of Allah,” Athens Journal of Philosophy 1, no. 2 (2022): 81.

17. Simpson, 121.

18. Pemberton, 83

19. Simpson, 121.

20. Mukhayyo Gaipova, “Medieval Central Asian Architecture,” The American Journal of Social Science and Education Innovations 3, no. 11 (2021): 3537

21. J. MahdiNejad, E. Zarghami, and A. Sadeghi HabibAdad, “A Study on the Concepts and Themes of Color and Light in the Exquisite Islamic Architecture,” Journal of Fundamental and Applied Sciences 8, no. 3 (2018): 1084.

22. McClary, 140.

23. Simpson, 121.

24. Gaipova, 3537.

25. Charles Hill, “A Euro Border Guard and Hybrid Warfare. An Art Theft Perspective: Human Dimensions and a Moral Imperative,” Connections QJ 15, no. 4 (2016): 112.

26. Hill, 116-117.

27. Colleen Margaret Clarke, and Eli Jacob Szyldo, Stealing History: Art Theft, Looting, and Other Crimes Against our Cultural Heritage (Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield, 2017), 21, 68.

28. Clarke and Szyldo, 70-71.

29. Hill, 118.

30. Clarke and Szyldo, 73.

31. Alberge.

32. MahdiNejad, Zarghami, and Sadeghi HabibAdad, 1084.

33. Soustiel and Porter, 30.

34. Soustiel and Porter, 169

35. Soustiel and Porter, 30.

36. Soustiel and Porter, 30.

37. Soustiel and Porter, 63.

38. Linda Komaroff, “Exhibiting the Middle East: Collections and Perceptions of Islamic Art,” Ars Orientales 30, (2000): 5.

39. Clarke and Szyldo, 66.

40. Komaroff, 5.

Works Cited

Clarke, Colleen Margaret, and Eli Jacob Szyldo. Stealing History: Art Theft, Looting, and Other Crimes Against our Cultural Heritage. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield, 2017.

Gaipova, Mukhayyo. “Medieval Central Asian Architecture.” The American Journal of Social Science and Education Innovations 3, no. 11 (2021): 112-118. https://doi.org/10.37547/tajssei/Volume03Issue11-19.

Hill, Charles. “A Euro Border Guard and Hybrid Warfare. An Art Theft Perspective: Human Dimensions and a Moral Imperative.” Connections QJ 15, no. 4 (2016): 111-120. https://doi.org/10.11610/Connections.15.4.06.

Komaroff, Linda. “Exhibiting the Middle East: Collections and Perceptions of Islamic Art.” Ars Orientales 30, (2000): 1-8. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4434259.

MahdiNejad, J., E. Zarghami, and A. Sadeghi HabibAdad. “A Study on the Concepts and Themes of Color and Light in the Exquisite Islamic Architecture.” Journal of Fundamental and Applied Sciences 8, no. 3 (2018): 1077-1096. https://doi.org/10.4314/jfas.v8i3.23.

McClary, Richard Piran. Medieval Monuments of Central Asia: Qarakhanid Architecture of the 11th and 12th Centuries. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2020.

Pemberton, Barbara B. “Job: Servant of Yahweh/Prophet of Allah.” Athens Journal of Philosophy 1, no. 2 (2022): 79-90. https://doi.org/10.30958/ajphil.1-2-2.

Simpson, St. John. “From Seizure or Donation of Antiquities to Their Identification and Research at the British Museum and Repatriation to the Countries of Origin: Recent Case Studies from Afghanistan, Uzbekistan and Iraq.” Journal of Art Crime 24 (Fall 2020): 9-23.

Jean Soustiel and Yves Porter, Tombs of Paradise: The Shah-e Zende in Samarkand and Architectural Ceramics of Central Asia (Saint-Rémy-en-l'Eau: Monelle Hayot, 2003), 34-35.