Kilic Ali Pasha Stained-glass Window Catalog Entry

Stained glass windows are found throughout the world, in many different types of architecture. It is very common to find magnificent stained glass windows in religious worship spaces. Churches and cathedrals are well known for their large, figural, stained glass windows. Mosques, while not known for their stained glass, can also be home to amazing stained glass windows. The Kilic Ali Pasha Mosque, located within the Kilic Ali Pasha Complex, is home to many beautifully intricate stained glass windows. This catalog entry will be focusing on the matching pair of windows on either side of the Mihrab.

The Kilic Ali Pasha Complex, located in Istanbul Turkey, is widely considered one of Mimar Sinan’s greatest and most important works[1]. The complex was built for Kilic Ali Pasha, a grand admiral. The complex was designed by Chief Architect Mimar Sinan. Today, it is widely regarded as one of Sinan’s greatest works. The mosque located within the complex was built as a modified, miniature version of the mosque Hagia Sophia. Construction of the mosque began in 1578 and was completed in the early 1580s[2].

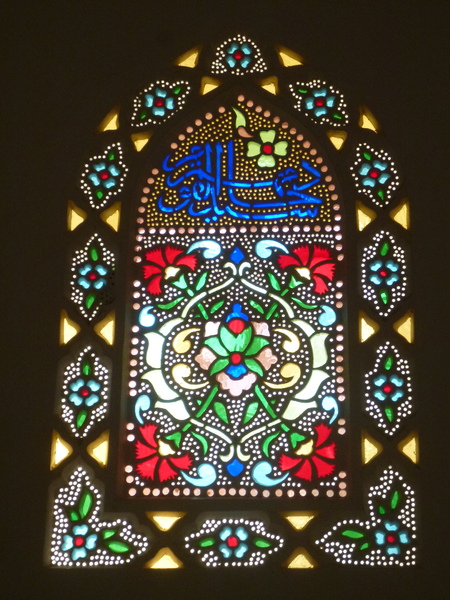

The Qibla wall is home to two stained glass windows, one on either side of the mihrab. The center of the windows is a solid green semicircle pane with scalloped edges. Above and below the center pane are blue panes with orange inscriptions from the Quran. These inscriptions stress the importance of prayer and devotions, as well as referring to the omniscience of Allah [3]. Surrounding this center design is a floral border composed of blue, green, red, and orange glass. Each color present in the design requires a specific glass composition and specific additives to the clear class in order to ensure the right color was made. Colors were often difficult to achieve as the same additives could create multiple different colors. In order to achieve the bright colors found in stained glass, metal oxides are added to clear, colorless glass. Blue glass is achieved from adding cobalt oxide, red is achieved with copper, green with iron, and yellow with sulfur[4]. While it appears simple, achieving the correct color of glass in the 1500s was far more difficult than it is today. The same additives could result in vastly different colors. Different amounts of additives and the furnace atmosphere played a key role in colors coming out right. Creating the right colors is a small part of the battle when creating large stained glass windows. The glass had to be thick enough, and strong enough to withstand the day to day weather of the area. It had to be able to withstand strong winds, rain, and sun without breaking. In order to achieve this, the glass pieces had to be a certain thickness. This became an issue for some colors, for example red, as when the pieces were as thick as needed to be, the color was so dark it was almost black and very little light would shine through[5].

Light not being able to shine through the windows was an issue as daylight and light had a big impact on the atmosphere and religious experiences of patrons. Light is used to illuminate and fill indoor spaces with spiritual and sacred meanings[6]. Stained glass windows add to the experience in ways that normal, clear windows do not. When light shines through the stained glass windows, the space is filled with mosaics of color full light on every surface. This can create an almost magical experience as the interior space is bathed in soft, colorful light. Light itself has an important meaning in Islam. It has significant, spiritual implications that relate to heaven and paradise. Light is also linked directly to Allah, as the Qur’an states that one of his first creations was light. Light is said to be an indication of how divine Allah is. As light is so important to the patron’s religious experience when in a mosque, mosques often have many windows. Often containing both stained glass windows and normal clear glass windows[7].

The Kilic Ali Pasha Mosque was not the first mosque to feature stained glass windows. Stained glass windows were a feature of many mosques of the time. The Kilic Ali Pasha Mosque wasn’t even the first of Sinan’s mosques to include stained glass windows. This can be seen in the Selimiye Mosque. The SelimiyeMosque is also home to beautiful stained glass windows. Construction of the Selimiye Mosque was completed shortly before the groundbreaking of the Kilic Ali Pasha Complex. The Selimiye Mosque is widely considered Sinan’s most perfect masterpiece and said to surpass Hagia Sophia in terms of architecture. Sinan used colored glass and stained glass windows throughout the mosque and its dome as a way to enhance the existence of divine light throughout the mosque[8]. The stained-glass windows present in the Selimiye Mosque, much like the Kilic Ali Pasha, has floral motifs and inscriptions from the Qur’an.

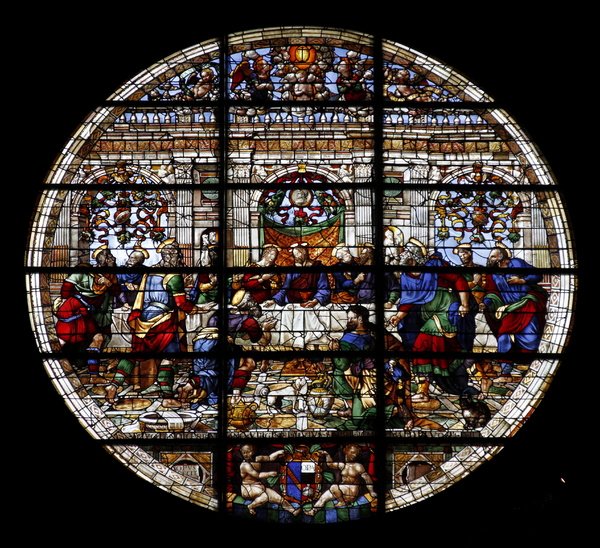

Mosques were not the only religious center to use stained glass windows. Stained glass windows are often found within churches and cathedrals around the world. The Cathedral of Santa Maria Assunto in Siena Italy is home many stained glass windows. A notable stained glass window in the cathedral is a large circular stained glass window depicting the last supper. This cathedral is home to many different stained glass windows, windows of all shapes and sizes, depicting many different scenes from the bible and different saints[9]. There is an interesting difference between the windows present within mosques and the windows present within churches or cathedrals. Stained glass windows found in churches and cathedrals very often have figural motifs. The windows depict saints, important scenes from the bible, and even Christ himself. The windows within Mosques do not depict human figures. They are often full of floral motifs and inscriptions from the Qur’an. The reason for this difference lies in how each religion views figural representation from their scripture. Islam does not allow for the physical representation of the prophets or Allah himself. This is viewed as idolatry. Instead, scripture is used to represent Allah and his teachings[10]. The Stained glass windows in both the Kilic Ali Pasha Mosque and the Selimiye Mosque are a good example of this. Both contain inscriptions of scripture with the messages from Allah, as well as floral motifs. Hagia Sophia is interesting to look at in this regard. As Hagia Sophia has been used as both a church and a mosque it is home to a wide variety of art styles. While there are figural representations in the art present, there are also Islamically influenced art pieces. For example, there are stained glass windows that do not contain the classic figural depictions often present in cathedrals. The windows contain inscriptions from the Qur’an and floral motifs.

The Kilic Ali Pasha Mosque could be viewed as a display of the power of both Kilic Ali Pasha and Mimar Sinan. Mimar Sinan is displaying the power he holds as the chief architect throughout the process of designing and building the mosque. The mosque, as a scaled down version of Hagia Sophia, shows how good of an architect he was. Sinan had access to very skilled craftsmen and artists as the chief architect. This is shown in the design of the Kilic Ali Pasha Mosque. For the stained glass windows, Sinan would have had to order large numbers of colored glass and then commission craftsmen and artists to build the windows[11]. The fact that Sinan had the ability to order large numbers of supplies and access to the craftsmen show the power he held as chief architect.

Kilic Ali Pasha used the designing and building of the complex in his name as a way to legitimize his power as an admiral. He was able to commission the chief architect of the empire to build his complex. As Sinan was the chief architect he was probably in high demand to design and build mosques and other buildings around the empire. The stained glass windows are also a show of power. In order to make intricate designs like the ones present in the mosque, a very skilled craftsman is required to design and put together the window. To have Mimar Sinan, chief architect, design and build your mosque, and utilize the many skilled artists and craftsmen required, shows how much power Kilic Ali Pasha had and how important he was. Architecture is only one of many ways people have legitimized their power throughout history. It is a way to show you belong and hold power. Often this is done through the size of the architecture, but this is not always possible because of resource or space constraints. When that is the case, the intricate nature and beauty of architecture can be used to legitimize one’s power. This is the case with the Kilic Ali Pasha Mosque. The size of the mosque may not depict the power Kilic Ali Pasha held, but the beautiful tile work, many intricate stained glass windows, and the fact that it was designed by Chief Architect, Mimar Sinan, himself, all legitimize the power Kilic Ali Pasha held.

[1]Ostwald, Measuring Form, 5

[2] Gülru, The Age of Sinan, 428

[3] Gülru, The Age of Sinan, 435

[4] Royce-Roll, Romanesque Stained Glass, 72-4

[5] Royce-Roll, Romanesque Stained Glass, 78

[6] Arel and Öner, Use of Daylight, 143

[7] Arel and Öner, Use of Daylight, 131

Citations

Arel, H. Ş., and M. Öner. 2017. “Use of Daylight in Mosques: Meaning and Practice in Three Different Cases.” International Journal of Heritage Architecture: Studies, Repairs and Maintence 1 (3): 421–29. https://doi.org/10.2495/ha-v1-n3-421-429.

Modj-ta-ba Sadria. “Figural Representation in Islamic Art.” Middle Eastern Studies 20, no. 4 (1984): 99–104.

Necipoğlu, Gülru. The Age of Sinan. London: Reaktion Books, 2005.

Ostwald, M.J., Ediz, Ö. Measuring Form, Ornament and Materiality in Sinan’s Kılıç Ali Paşa Mosque: an Analysis Using Fractal Dimensions. Nexus Netw J 17, 5–22 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00004-014-0219-3.

Royce-Roll, Donald. “The Colors of Romanesque Stained Glass.” Journal of Glass Studies 36 (1994): 71–80.

Thompson, Nancy M. “Designers, Glaziers, and the Process of Making Stained Glass Windows in 14th- and 15th-Century Florence.” Journal of Glass Studies 56 (2014): 237–51.