Curtain for the Door of the Ka‘bah- Catalogue Entry

The Curtain for Door of the Ka‘bah

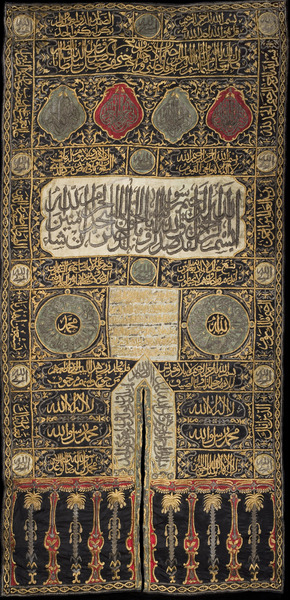

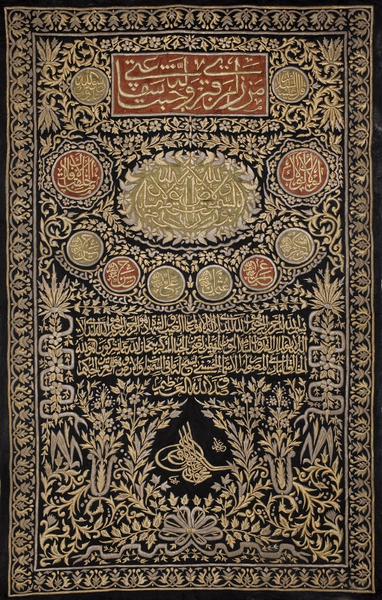

The Curtain of the door of the Ka’bah is a kiswa that was patronized by Sultan Abdulmejid I. It was presented by Muhammad Sa’id Pasha who was the governor of Egypt in 1855-6 AD. The measurements of the kiswa are 510 by 234 cm. This kiswa is made of black silk and it is adorned with green, red, and cream appliques with gold and silver wire embroidery. Kiswas are the covering of the Ka’bah and are renewed either annually or biannually [1]. The part of the kiswa that covers the wall is referred to as the thawb (garment) while the part covering the door is called the burqu’ (face veil). As seen in the picture above, the curtain of the door is decorated with several verses of the Quran which hold great meaning to the Islamic community. Another important feature within the design of the Curtain of the Door of the Ka'bah is the inclusion of the patron as well as the production date [2]. The purpose of this measure was to allot proper credit and praise to those who have made contributions, however, it led to greed and competition among the people.

When and where the Curtain of the Door of the Ka’bah was made

Similar to many other kiswas, the Curtain of the Door of the Ka’bah was made by the Mamluks in Cairo, Egypt. The Mamluks were known for their high-quality textiles and building materials. The Mamluks, for centuries, had been bestowed the honor and privilege to produce the kiswas, and funding for the production was provided by the Egyptian government [3]. As a result of this great responsibility of manufacturing the covering for the holiest site in the Islamic community, the Mamluks were granted a very high status in society [4]. Once made, the kiswas, ready to adorn the Ka’bah, would then be delivered to Mecca, however, this was not always the smoothest journey.

Purpose of kiswa

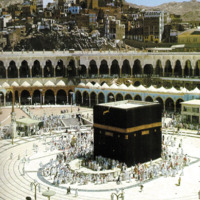

The purpose of the kiswa is not to cover the Ka’bah as a means of concealing it so that it cannot be seen, but rather, to honor and protect it. Stretching far back to pre-Islamic times, tribes made tents called qubba to protect their idols. The kiswa is meant to protect the sacredness of the Ka’bah, not solely to make it hidden.

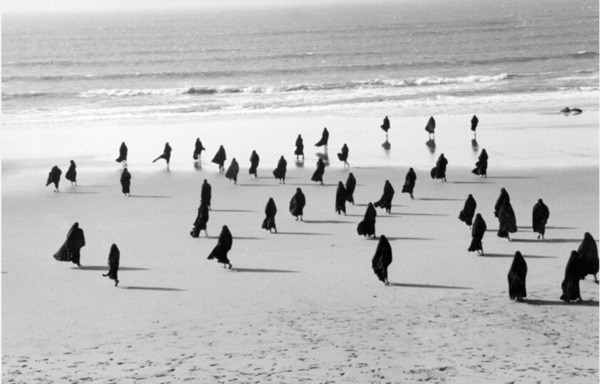

The role of kiswas in many ways is very similar to that of the hijab or Islamic veil. The use of a ‘veil’ in Islam is not to oppress Muslim women, as very commonly interpreted by the Western world and the media, rather, the hijab aims to protect Muslim women from the attention of ill-intentioned people. The veil is a commandment of God upon all Muslim women. By following this, a Muslim woman is encouraged to focus on her nearness to God and to stray away from worldly temptations and pleasures. Covering up does not lessen the beauty or importance of a person or an object, as in the case of the Ka'bah, rather, it adds to its beauty and purity. However, Muslim women face much backlash from Western society for wearing the hijab. In many pieces of artwork such as The Rapture, which is the picture on the right, artists attempt to show viewers the importance of the hijab to the identity of a Muslim woman and how it liberates her from the material and vain standards of society. Just as the hijab is used to protect Muslim women, who are considered very precious, the kiswa protects the Ka’bah [5]. Another common comparison of the relation between the Ka’bah and the kiswa is that between the skin covering the body [6]. The skin is not directly thought of as ‘covering’ the body but instead, it protects the body. Covering the Ka’bah does not diminish its spiritual power or hinder the path to discovering it, rather, it gives the viewer a reason to explore the Ka’bah and unveil its inner, spiritual beauty.

Embroidery and Inscriptions

As seen on the left, The Curtain for the Door of the Ka‘bah has been inscribed with various Quranic verses including surah al-Ikhlas (112), surah al-Naml (27:30), surah al-Isra’ (17:80), and surah al-Fath (48:27). The Shahada, the ultimate pledge of Islam, can also be seen around the entrance of the door. The purpose of these verses is to turn the attention of the viewer to Allah, the Almighty, and His Prophet [7]. While the designs and formats of kiswas have been altered over time, a consistency remains in the integration of the words from the Holy Quran and their importance to the kiswas’ design plan. As well as being used to cover the Ka’bah, kiswas were also delivered to Medina to be used as a cover of the Prophet’s tomb as well as his companion’s graves [8]. On the right is shown the Curtain (Sitarah) from the Tomb of the Prophet in Medina. This curtain is in many ways similar to the one covering the Ka’bah. The Curtain (Sitarah) from the Tomb of the Prophet was also made in special factories in Cairo and is renewed on an annual basis. However, rather than being transported to Mecca, this curtain was taken to Medina to be placed on the Prophet's tomb [9]. On the top of this curtain a hadith, which is a saying or practice of the Prophet, is transcribed along with several verses of the Quran such as ayah al-Nur, “God is the Light of the heavens and the earth,” followed by the names of all of the Prophets companions [10]. While the two kiswas may slightly differ in their ornamental designs, they each incorporate surahs of the Quran which aim to unite the viewer with His creator. While the many colors and embellishments added to the kiswa designs may begin to lead one astray and inclined toward material beauty, the calligraphy of the verses in the Quran aims to guide the viewers back to Allah by reminding them of His supreme characteristics and that He is the beholder of all beauty and power.

How does the Curtain for the Door of the Ka‘bah relate to the theme of Extravagance?

Patronizing the most beautiful and extravagant kiswa became the goal of many rulers as they saw it as a means to show their strength and power. The Curtain for the Door of the Ka’bah, full of embroidery and inscriptions, was the most intricate part of the covering of the Ka’bah. In addition to the Quranic verses, the embroidery consisted of designs such as chevron or zig-zag, or floral patterns too. The name of the person who donated or provided the funding for the kiswa was also to be included in the design and, for some, this became an incentive for them to contribute towards the donation. Through generations, the kiswa became more and more politicized, and its production became a competition [11]. The original kiswas were once made of palm leaves and animal skins; however, with time, they were made of the finest silks and fully embellished. The designs and formats of kiswas were routinely altered and advanced with respect to the likings of the leading ruler of the time [12]. Some may argue that rather than the spiritual importance of the kiswa covering the Ka’bah holding high esteem in the hearts of the people, the honor and social status that came with kiswas became the motive for many. Kiswas had become a symbol of political power and status.

How does the Curtain for the Door of the Ka‘bah relate to the topic of the moral implications of extravagance?

The craftsmanship of kiswas such as the Curtain of the Door of the Ka’bah displays the moral implications of extravagance. Rather than truly embodying the religious meaning of the kiswa, workers were put under harsh conditions and the construction of the kiswa was motivated by money and fame instead of morality. The intricacy and detailing of the embroidery on the curtain of the door was far more advanced than those on any other part of the kiswas and this difficult task was to be done by the workers under strict conditions. In most cases, the whole family including the mother, father, daughters, and sons would be employed by the factory. Workers would work long hours 6 days a week, beginning work early in the morning at 8. In addition to the long working hours, the factory held very strict rules and regulations for the workers. The workers were given a very tight production schedule, and they were penalized if they were unable to meet the goals set for them. In addition to the many rules and regulations, they were only allowed one day off. The factory management was solely invested in producing the best and most plentiful kiswas, and they took no concern about overburdening the workers [13]. The factory owners were not concerned by the workers' well-being rather the kiswa production was their primary concern. They became blinded by their lust for fame and money and lost their sense of humanity and empathy. Sometimes people are overtaken by extravagance and greed. For instance, en route to Mecca, the kiswa, 'The Holy Carpet,' had to be protected not from dust or dirt but from people with malicious and materialistic-driven intentions. On one occasion, while it was en route to the Ka'bah a kiswa was stolen by the Bedouins, an Arab tribe. It was held captive for a ransom of $3,000. The respect for the kiswa had dropped to such a low extent as for it now to have become a means of attaining money [14]. The spiritual significance of the kiswa began to diminish, transitioning its value to a source of political and societal gain.

Footnotes

1 Rogers, J. M, 340-343

2 O’Meara, Simon, 132-133

3 "The ‘Kaaba’ and the Holy Carpet," 88

4 Mackie, Louise W, 127–46

5 Mackie, Louise W, 127–46

6 Kenzari, Bechir, and Yasser Elsheshtawy, 18

7 O’Meara, Simon, 135

8 Rogers, J. M, 340-343

9 Al-Mojan, Mohammad, 184–94

10 Rogers, J. M, 340-343

11 İpek, Seli̇n, 289-290

12 İpek, Seli̇n, 289-290

13 Al-Mojan, 184–94

14 “The ‘Kaaba’ and the Holy Carpet,” 88

Work Cited

Al-Mojan, Mohammad. “The Textiles Made for the Prophet’s Mosque at Medina.” In The Hajj: Collected Essays, edited by Venetia Porter and Liana Saif, translated by Liana Saif, 175–94. London: The British Museum Press, 2013. https://archive.org/details/TheHajj/page/n193/mode/1up

İpek, Seli̇n. “Ottoman Ravza-I Mutahhara Covers Sent from Istanbul to Medina with the Surre Processions.” Muqarnas 23 (2006): 289–316.

Kenzari, Bechir, and Yasser Elsheshtawy. “The Ambiguous Veil: On Transparency, the Mashrabiy’ya, and Architecture.” Journal of Architectural Education (1984-) 56, no. 4 (2003): 18-19.

Mackie, Louise W. “Toward an Understanding of Mamluk Silks: National and International Considerations.” Muqarnas 2 (1984): 127–46.

O’Meara, Simon. “The House as Dwelling.” In The Kaʿba Orientations: Readings in Islam’s Ancient House, 131–57. Edinburgh University Press, 2020.

Rogers, J. M. The Arts of Islam : Masterpieces from the Khalili Collection. London: Thames & Hudson, 2010.

"The ‘Kaaba’ and the Holy Carpet." Scientific American 81, no. 6 (1899): 88.