Silk Robe Fragment Catalogue Entry

Islamic silk textiles transcended time, continents, social classes, and cultures. The history of silk production in Eurasia dates back to even before the rise of the Islamic world. The Sassanian dynasty in modern day Iran (226-651 CE) made silks that were traded across the world and influenced other silk making and fashion. After the Fall of the Sassanian Dynasty, the Abbasid caliphate began in 750 CE and established its capital in Baghdad in 762 CE, and silk production in that area continued with similar style and technique.[1] The influence of the Sassanian dynasty can be seen in the patterns and styles of the continued Islamic production of silk.

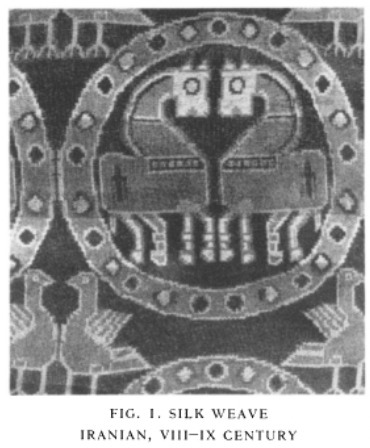

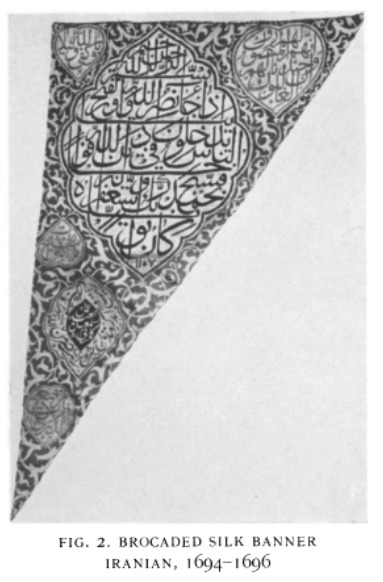

Two early Iranian silk textiles give insight to the continued Sassanian influence on Islamic silk style, as “both the motives and the patterns are based on Sassanian traditions, which continued in the Islamic era.”[2] The features of silk textiles were very meaningful, and “were largely shaped by a set of social, economic, cultural, and aesthetic variables.”[3]The symbols and style of Islamic silk robes and textiles carried political, institutional, cultural, and religious significance. These “honorific garments served the dual purpose of proclaiming one’s allegiance and representing a ruler’s mark of honor.” [4] In the Abbasid dynasty, textiles were often used as gifts of honor, and the quality and design would depend on the receiver’s social status.[5] Silks would often carry the markings of certain rulers, institutions, or even Qur’an inscriptions. This particular piece does not have a text inscription, but the other, triangular textile, shows an example of this. The inscriptions are “references to the help of Allah and to victories indicate that the banner was probably used for religious purposes or as a battle flag by the Iranian army.”[6] Silk textiles were used in all different parts of Islamic culture. Other common silk adornment included geometric patterns, shapes, and motifs, floral or vegetal ornamentation, and animals, sometimes mythical. This particular robe fragment shows winged horses on a geometric pattern.

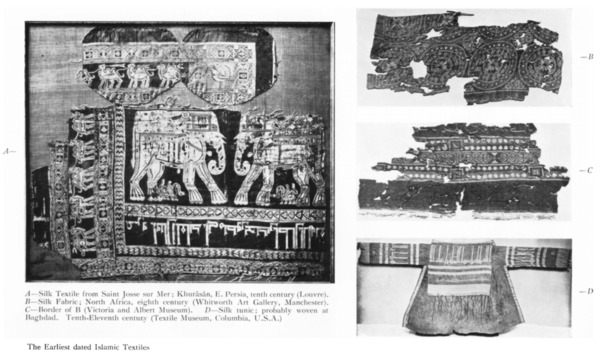

These pattern elements are found on other Sassanian art and architecture. Albert F. Kendrick, in his article about some of the earliest dated Islamic textiles, referenced above, discusses decoration on some ancient Sassanian sculptures bearing similar patterns, saying they “belong to the early years of the seventh century, rather more than a century before the date of the silk. As an ornamental border the design had a wide and lasting vogue. With a single row of pearls, but retaining the square jewels, it is often found on the Sassanian silks, and it occurs frequently in the wall-paintings at Samarra, Mesopotamia, of the middle of the ninth century.”[7] This pearl-row pattern is also seen in two of the other textiles shown here, showing the lasting influence of Sassanian styles on Islamic silks. The artistic style on silk was not exclusive to silk, and similar patterns, depictions, and inscriptions can be found on other Islamic art and architecture.

The style and design of silk made for the common people was inspired by the significant motifs on the silk of the upper classes. This makes sense, since the production of silks in the Islamic world mostly happened through the Tirazsystem, large royal palace textile factories.[8] In this way, silk production was funded by the state, and certainly benefited in quantity and quality from this. But not all silk was produced in royal palaces, as “there were two kinds of tiraz factories in the Islamic world: those of the caliphate, which produced garments for the family of the caliph and honorary robes for the warehouse of the caliphate, and the public tiraz, which produced garments with inscribed bands for the public.”[9]Thus the public also had access to the finest quality silks with the latest fashion and trends. Who doesn’t want to wear the same awesome robes as their ruler? Although the patterns, symbols, and motifs on silks originated from political or religious significance, and “the tiraz system was part of the state machinery of the Islamic empire, it never exercised a monopoly over certain textiles. Islamic law had no rules prohibiting Muslims from moving up in society.”[10] Unlike other empires, such as Byzantium or Tang China, Islamic society did not have a strict socio-economic hierarchy with a restrictive dress code attached to it. In places where silk was abundant, it was often even used as payment for servants, and even non-Muslims could wear fine silks, such as Jewish people, who “wore gorgeous, bright-colored clothes, whose quality was equal to that of garments made for Muslim rulers.”[11] Silk textiles had a place in almost every part of Islamic society, and at every socio-economic level as well. Due to position of silk as most valuable and important commodity within Islamic culture, trade was a prestigious profession, and traders often were regarded with high socio-economic status. Especially because Muhammad was a merchant himself.[12] Silk thus made its way into every part of society and people’s lives, and as a textile, it was important for dress and home use in leisure activities.

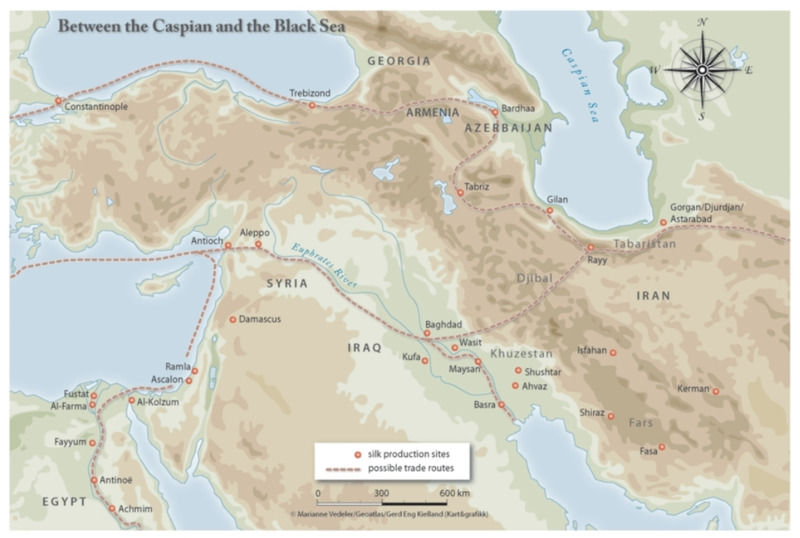

Also shown is a map with major locations of silk production in Eurasia, where “in the early Islamic period fine textiles were woven in all the provinces of the Muhammadan empire … among the important Abbasid centers of weaving which we know from inscriptions on existing textiles were Nishapur and Merv, both in the province of Khurasan in eastern Iran.”[13] Being state funded and organized through the tiraz system, silk production was abundant in the Islamic world. It was then traded all around Asia, Europe, and North Africa, and “with the development of a silk industry in the Islamic countries, and with rising demand for silk in Europe, a market formed around the Mediterranean basin.”[14] The Mediterranean connected Europe, North Africa, and western Asia (or the Middle East), and so was incredibly important for inter-continent and culture trade. Silk was valuable across the world, and often held religious or political significance in other cultures, the same way it did in Islamic culture. The European Christian world used Islamic silks for religious and political purposes. The silk trade linked east Asia to western Europe through the silk road, whose routes “passed through some of the most desolate and inhospitable terrain on earth.”[15] This is an incredible historical phenomenon: the commodity of silk linked many different cultures, surpassed physical barriers to its trade, and maintained its cultural value in each. If that doesn’t show the value of silk textiles, then I’m not sure what would.

The fragment shown in this exhibit shows some of the most common and popular elements of Islamic silk, called Parand and Parniyan. These textiles “were signified by their characteristic pearl-roundels symbolizing the stars of heaven, framing beasts, and birds as well as formal designs.”[16] This piece shows pearl-roundels arranged on a geometric grid with winged horses drinking from streams with trees in the background. The winged horses may be inspired from the story of the prophet Muhammad’s night journey to heaven on the back of a buraq, or winged horse, although the buraq is often depicted with a human head, so the horses on the robe are not quite the same thing. The robe fragment shows Sassanian influence with the pearl strips and outlines. It was most likely produced in early Abbasid Iran around the 7-8th century CE in a royal palace textile factory, perhaps shortly after the establishment of the Caliphate’s capital in Baghdad. Although some Islamic textiles were dated due to religious custom[17], this one is not, which leaves a little mystery as to its origin.

Clothing is and was an important part of leisure, and this robe, not showing any explicit political or religious significance, could have been worn in leisure activities, such as family gatherings, public social events, and shopping. Silk textiles, with their complex style, production, and trade were an important part of people’s leisure lives and activities.

[1] Vedeler, Marianne. Silk for the Vikings, (Oxford: Oxbow Books, 2014), 81.

[2] Dimand, Maurice S. “Two Iranian Silk Textiles.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 35, no. 7 (1940): 142.

[3] Jacoby, David. “Silk Economics and Cross-Cultural Artistic Interaction: Byzantium, the Muslim World, and the Christian West.” Dumbarton Oaks Papers 58 (2004): 197.

[4] Hedayat Munroe, Nazanin. “Early Islamic Textiles: Inscribed Garments.” Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2012. Accessed on May 1, 2023. https://www.metmuseum.org/exhibitions/listings/2012/byzantium-and-islam/blog/topical-essays/posts/inscribed-garments

[5] Vedeler, Silk for the Vikings, 82.

[6] Dimand, “Two Iranian Silk Textiles,” 143.

[7] Guest, Rhuvon, and Albert F. Kendrick. “The Earliest Dated Islamic Textiles.” The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs 60, no. 349 (1932): 186.

[8] Vedeler, Silk for the Vikings, 82.

[9] Liu, Xinru. “Silks and Religions in Eurasia, C.A.D. 600-1200.” Journal of World History 6, no. 1 (Spring 1995): 43.

[10] Liu, “Silks and Religions in Eurasia, C.A.D. 600-1200,” 45.

[11] Liu, “Silks and Religions in Eurasia, C.A.D. 600-1200,” 46.

[12] Liu, “Silks and Religions in Eurasia, C.A.D. 600-1200,” 45.

[13] Dimand, “Two Iranian Silk Textiles,” 143.

[14] Liu, “Silks and Religions in Eurasia, C.A.D. 600-1200,” 46.

[15] Liu, “Silks and Religions in Eurasia, C.A.D. 600-1200,” 25.

[16] Vedeler, Silk for the Vikings, 83.

[17] Guest and Kendrick, “The Earliest Dated Islamic Textiles,” 185.

References

Dimand, Maurice S. “Two Iranian Silk Textiles.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 35, no. 7 (1940): 142-144.

Guest, Rhuvon, and Albert F. Kendrick. “The Earliest Dated Islamic Textiles.” The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs 60, no. 349 (1932): 185-191.

Hedayat Munroe, Nazanin. “Early Islamic Textiles: Inscribed Garments.” Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2012. Accessed on May 1, 2023. https://www.metmuseum.org/exhibitions/listings/2012/byzantium-and-islam/blog/topical-essays/posts/inscribed-garments

Jacoby, David. “Silk Economics and Cross-Cultural Artistic Interaction: Byzantium, the Muslim World, and the Christian West.” Dumbarton Oaks Papers 58 (2004): 197-240.

Liu, Xinru. “Silks and Religions in Eurasia, C.A.D. 600-1200.” Journal of World History 6, no. 1 (Spring 1995): 25-48.

Vedeler, Marianne. Silk for the Vikings, (Oxford: Oxbow Books, 2014), 81-96.