Maydan Coffeehouse Catalogue Entry

The Safavid dynasty was one of the most significant ruling dynasties in Iran. They ruled from 1501-1736 and, along with the Ottoman and Mughal Empires, held the title of one of the gunpowder dynasties.[1] One reason that the Safavid dynasty became so significant was because of the relationship the ruler, or Shah, had with his citizens. A relationship that would be developed through the introduction of coffeehouses to Iran.

The introduction of coffee to Islam started in the early sixteenth century, with people mainly drinking it before their nightly rituals because the natural caffeine would help them stay awake and alert during the practices.[2] However, as the drinking of coffee became more widespread, people started drinking it as not just a substance to help them stay awake but as a social beverage. It also became popular because it was a flavorful drink that did not contain alcohol. The Safavids practiced Shi’a Islam, and as Muslims, they could not consume alcohol. So, coffee became a nice option. The most common place to socially enjoy coffee was in a coffeehouse, which the Safavid dynasty—and, Shah Abbas, who ruled from 1588-1629—constructed many of.[3]

He would be important to the building of coffeehouses because he took the first step in moving the capital of the Safavid empire to the central city of Isfahan, Iran, where later the Maydan-i Naqsh-i Jahan Square, or the Maydan, would be built.[4] In the structure of the Maydan, coffeehouses were an integral part of the main building program, so much so that when people visited, they could sense the “close association of the coffeehouses with the Maydan.”[5] The coffeehouses stretched alongside the northern side of the Maydan, and introduced a seamless environment between the outside and inside spaces.

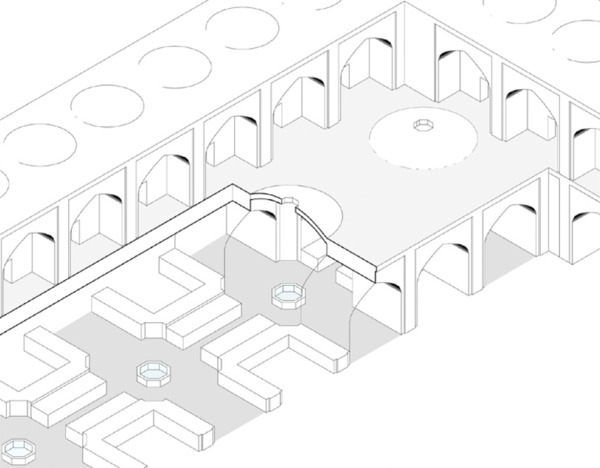

This was facilitated by large cutouts in the building that allowed for fresh air and natural light to enter the space and the smells and noises of the coffeehouse to leave the space.[6] Since the coffeehouses were along the square, people could look in through these large windows and see into the coffeehouse and watch the people sitting and talking. This sight invited those passing by to also make a stop inside the coffeehouse and sit down, which there were few other places along the Maydan to do so. There would often also be chairs outside the building, which allowed for even easier access to sit down and have a drink. When it comes to how many coffeehouses there were in the Maydan, it is difficult to come to an accurate conclusion, as very little remains of the original space. Luckily, there are many first-hand sources describing what they saw back when the coffeehouses where still standing. So, scholars believe the coffeehouse to be almost a complex of coffeehouses with six or eight total making up the space, which proves that this must have been a huge building to walk past.[7]

In the inside of the coffeehouses, there was amphitheater-style seating and a water basin with running water in the center of the room for filling up water pipes.[8] The rooms were very spacious with high ceilings, which allowed for many people to sit inside the coffeehouse and relax while chatting with other people in the community. This community also allowed a space for both women and people of lower classes to take part in the activities. They could speak between socioeconomic lines in a place that was not built around religion. Coffeehouses became a fourth place for people to go to if they did not want to go to work, home, or the mosque.[9] This was very important because it built a social space outside of religion. Shah Abbas, who facilitated the coffeehouse creation, was unusually tolerant of other religious beliefs, even though the previous Safavid Shahs were not.[10] This could be in part why the coffeehouse was such an important space to him. It allowed for people of all religions to share their ideas, since spaces like this had not previously existed in this form.

The idea that women could be in spaces like this was revolutionary as well because typically spaces like these were reserved for men. The Maydan coffeehouse allowed women to come and go as they please, but a different Safavid coffeehouse in the Chahar Bagh would close on Wednesdays and only women were allowed to be inside.[11] This meant they could remove their hijab if they pleased, and they would solely be around women to talk as they wish. The Maydan was different in this aspect because they would have women and men in the space at the same time, which meant both genders could connect with one another, whereas the Chahar Bagh coffeehouses did not allow for that type of interaction.

Within the coffeehouses, people could listen to more than just conversation. Often, poetry was being written and read, and there could also be people playing instruments and telling stories by the fountain in the middle of the room.[12] One of these patrons that might be reading poetry or speaking to others was the Shah himself, who would frequent the coffeehouses during their prime to speak with the people under his rule. While today it might be common for a leader to speak with his constituents, at the time this was rare for a leader to do, and to do so frequently.

For example, another member of the gunpowder dynasties made it so the ruler would never have to be seen by the community. The Ottomans and their Topkapi Palace had structures put in place that allowed the sultan to move within the walls and spy on the members of the palace with nobody knowing where he could be at any time.[13] He could stare out grated windows and nobody would be any the wiser to if they were being watched. This inflicted a tension among the people as they always acted as though they were always being watched because they could never be sure if this fact was true or not.

In the late 16th century, the Ottoman Empire was also taken with the invention of coffee and built their own coffeehouses to distribute the product and for the community to have a leisure space. However, the interior design was laid out differently than those of the Safavids. There were corner platforms for regulars to sit on surrounded by narrows fenced-in staircases, which could be compared to how mosque interiors often looked.[14] This was most likely intentional since the Ottoman Turks were not as religiously tolerant as the Safavids. The nod to mosque architecture was probably purposeful and did not give the patrons a space away from religion like the coffeehouse at the Maydan. These regulars atop the platform were also seated higher than the new customers, which created a hierarchy among the patrons. This is in stark contrast to the Maydan coffeehouse that put all customers on level-footing, even the Shah.

Clearly, the Safavid empire took a different approach, at least at first, with how the Shah would be presented. Within the coffeehouses, the Shah could sit down and speak candidly with other about politics and other subjects of conversation. There would be no punishment for those who spoke ill of him, and this allowed for a comfortable environment where people could speak freely about whatever they chose. Eventually, this did take a turn as people became too outspoken, and the empire began to feel threatened. In 1695, a clamp down began on coffeehouses because the empire felt that they had encouraged too much socialization between the different socioeconomic groups. Since people could now speak openly about everything, people in power began to worry about a potential uprising among the people. This clamp down was led by Sultan Husayn because he was worried about the “increasing degree of freedom and autonomy” that patrons of coffeehouses were achieving by consistently going to these spaces.[15]

This shut down of the coffeehouses is one of the reasons why it is difficult to get a complete plan of what the Maydan coffeehouse architecture looked like. Since patrons could no longer go into these establishments, nobody was kept to maintain them in their former glory. What once was a place of commerce, leisure, and conversation fell to the wayside. But even though this building is no longer standing, it is important to look back on what the Maydan-i Naqsh-i Jahan once stood for. It was a place of relaxation for the community of Isfahan to speak with one another while enjoying a cup of coffee. They could enjoy art and poetry while openly discussing their thoughts about the place they lived without feeling watched or threatened. Coffeehouses became a place of leisure for all those who entered the space, and it became an integral part of how the Safavid Empire functioned.

[1] Farshid Emami, “Coffeehouses, Urban Spaces, and the Formation of a Public Sphere in Safavid Isfahan,” Muqarnas 33 (2016): 191.

[2] Ralph S. Hattox, Coffee and Coffeehouses: The Origins of a Social Beverage in the Medieval Near East (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1985), 14

[3] Stephen P. Blake, Half the World: The Social Architecture of Safavid Isfahan, 1590-1722 (Costa Mesa: Mazda Publications, 1999), 8

[4] Blake, 11

[5] Emami, 191

[6] Emami, 188

[7] Emami, 192

[8] Emami, 191

[9] Emienül Karababa and Güliz Ger, “Early Modern Ottoman Coffeehouse Culture and the Formation of the Consumer Subject,” Journal of Consumer Research 37, no.5 (2011): 11

[10] Blake, 9

[11] Emami, 190

[12] Emami, 204

[13] Gülru Necipoğlu, “Framing the Gaze in Ottoman, Safavid, and Mughal Palaces,” Ars Orientalist 23, (1993): 304

[14] Karababa and Ger, 11

[15] Babak Rahimi, Theater State and the Formation of Early Modern Public Sphere in Iran: Studies on Safavid Muharram Rituals 1590-1641 CE (Boston: Brill, 2012): 196