Nishapur Chess Pieces Catalogue Entry

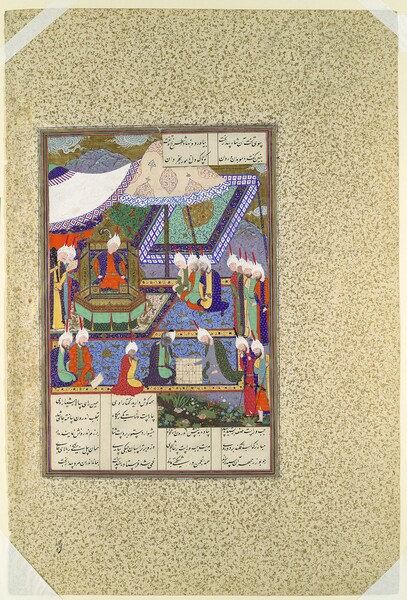

Chess has a rich historical tradition throughout the Islamic world, particularly in courtly contexts. Most evidence asserts that the game originated in India and spread to Persia, where Arabs soon encountered the game following conquests in what is now Iraq and Syria.[1] By tracing the word for chess in Arabic, shatrani, which comes from the Persian chatrang, which itself is derived from the Sanskrit word chaturanga, a linguistic history of the game’s development and spread is revealed[2]. The Sanskrit chaturanga translates to “four members of the array,” which refers to the four pieces represented as elephants, horses, chariots, and foot soldiers. The mythic tradition in India regales how a Hindu Brahmin named Sissa created the predecessor of chess for a king, although the exact date and location for the creation of the game are unknown.[3] The literary tradition provides a similar chronology. One story described in the Iranian national epic poem, the Shahnameh (“Book of Kings”), apprises how the Raja of India presented chess as a riddle to avoid paying tribute to the Persians, who in turn sent a backgammon board to India after Buzurjmihr mastered the game.[4] Although other games including Astronomical Tables, Backgammon, cards, and checkers were played, Chess became the favorite indoor pastime and competition for the ruling classes in the Islamic World. It was popular with many leaders, including Umayyad caliphs like Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan and later Abbasid caliphs like Hārūn al-Rashīd, al-Mutawakkil, and al-Mu’tadid.[5][6] A successful ruler was not only expected to defeat the enemy on the battlefield but should be capable of winning a game of wits on the chessboard as well. The game soon spread throughout every region of the Islamic world and was popular from Samarqand in Central Asia to Sicily and al-Andalus in Europe.

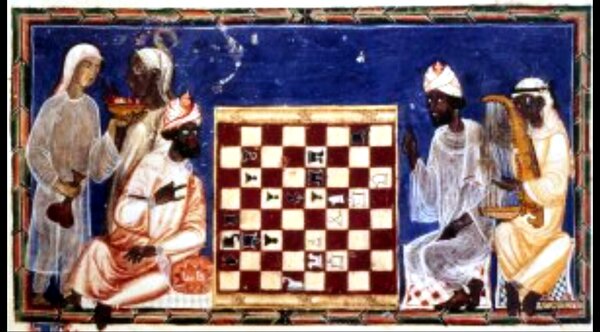

Apart from the detailed description within the Shahnameh, chess is discussed in other manuscripts including The Libro de ajedrez of Alfonso, el Sabio from the thirteenth-century court of Alfonso X in Castile. The manuscript is a product of a Christianized Muslim land that remained quite multicultural and religiously diverse; images contained in the work depict people of several occupations, Black and white skin, and Muslims, Christians, and Jews.[7] However, this diversity is not reflected in its class representations, which are restricted mostly to the courtly context of rulers, nobles, and palatial servants.[8] Despite likely being written by Christian scribes, as evidenced by the French Gothic writing, the clear Muslim influence is apparent.[9] The text describes chess itself, and in the tradition of earlier Islamic treatises, provides game problems and solutions. Where the text differentiates itself, is through its figural depictions of actual chess pieces on the board, thus creating more interactive chess problems—illustrating a link between text and visuals not found in earlier Islamic texts.[10] These images represent the earliest practical chess manual in history, proving the reader with a hands-on chess tutorial. In total, the manuscript contains 103 chess problems, 88 of which are Muslim in style and 15 of which are of a European mode.[11] The immense detail of these illustrated chess problems suggests their craftsmen knew the game and its strategy intimately, even including cultural superstitions surrounding hand placement to ward off the evil eye and ensure good luck.[12] This manuscript also emphasizes the cultural and imperial importance of chess, citing it as the “royal game,” “most noble of games,” and that it “demanded greater skill” than all other games as well.[13] This perceived kingly nature is twofold, stemming both from the warfare objective of capturing an opposing king and its perceived royal historical lineage from India and Persia. Literary depictions like these illustrate the importance of chess in courtly life and emphasize that the game was likely restricted for the enjoyment of the wealthy and powerful.

The earliest chess pieces were figural in nature. That is, they depicted more “naturalistic representations” of human beings, animals, and structures.[14] The earliest identifiable figural chess pieces were a set of carved ivory figures from the ancient city of Samarqand in modern-day Uzbekistan.[15] Several extant pieces depicting elaborately carved elephants, some with humans and loads mounted atop them, used as bishop, king, and queen pieces have been unearthed, for example. However, these distinct figures would soon become simplified. Later elephant figures underwent several degrees of abstraction until they became “a simple cylinder with notches cut at the front to suggest two protuberances”.[16] Chess pieces became abstracted soon after the Arab conquests of lands throughout the Middle East and Central Asia. The earliest known abstract figures were those uncovered at the site of the Tepe Madraseh complex in Nishapur, an ancient city in modern-day Iran by Charles K. Wilkinson in 1939.[17] The bustling city is survived by a rich archeological footprint. The Nishapur chess set was excavated from a house dating to the ninth century CE and represents some of the earliest abstract Islamic chess pieces.[18] Nishapur was initially settled as a Sassanian citadel and military outpost, however, it transformed into a key international hub for Silk Road trade, connecting three continents by the ninth century.[19] These figures were also carved from ivory, but their shapes are less defined. The shift away from figural representation is likely a result of the religious and moral controversy surrounding the game, especially under Arab rule. Questions over the legality of chess occurred after the death of the Prophet Muhammad who, dying before major contact was initiated with Persia, left no Qur’anic writings or revelations about the game to inform the rulings of religious scholars.[20] The abstracted form of chess popularized in the Medieval period would dominate for nearly seven centuries throughout the Islamic world. It would not be until the rise of the sixteenth-century Mughal dynasty in Northern India that figural chess pieces would rise to become fashionable and acceptable once again.[21]

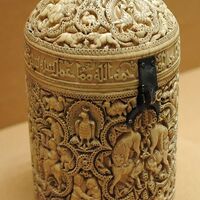

It is significant to note that the medium of the Nishapur chess pieces is carved ivory. Historically, ivory was one of the most expensive and status-illustrating materials in ancient and medieval times, and Islamic empires particularly favored the material. Their relatively common appearance in the holdings of both museums and private auctions suggests that ivory was the most common material utilized in Medieval chess sets. Most of the ivories in the Islamic world were sourced from elephant ivory, which perseveres remarkably well, but several pieces crafted from the cheaper and less durable bone have also been found.[22] The limitations imposed by the size and structure of elephant tusks meant that usually the wider, hollow top-third of the tusk was used in the crafting of larger objects like pyxies or plated furniture while the remainder was often employed for smaller objects like chess and game pieces.[23] The Islamic desire for ivory was aided by its proximity to, or even control over, the trade of the material from West Africa and India. The rarity of the material and complexity required for its craftsmanship meant carved ivory pieces became a source of imperial competition between the Byzantines, Normans, and various Islamic polities surrounding the Mediterranean.[24] This meant only the very wealthiest strata could afford to access such items: “The fact that so many game pieces are made from this expensive and luxurious material might suggest that chess and backgammon were elite pastimes.”[25] Intricately carved ivory pyxies, for example, were a favorite gift of royals in al-Andalus. There are several major geographic traditions or styles of carved ivory chess pieces; largely, they can be grouped into those made in the Eastern and Western Islamic World. While both styles are abstracted in nature, the Eastern style, predominant in Iran and Central Asia, like those found at Tepe Madrasa in Nishapur, were quite plain in decoration with abstracted, but still illusionary forms of the previous figural pieces. In contrast, the Eastern or “Mediterranean Style” which was crafted in Sicily, Southern Italy, and Egypt were decorated with “incised dots and circles arranged in cross or vegetal motifs or in undulating dots” and were more overtly abstracted.[26] The abundancy of chess sets made entirely of one material suggests that early Islamic chess pieces may not have been distinguished by their color, but instead, a proficient player was required to distinguish their pieces from their opponents by board placement alone.[27] This element of visual difficulty perhaps played a part in why the game became such a symbol of mental fortitude throughout the Medieval period.

Although the most common, ivory was not the only medium employed for chess sets. After ivory, rock crystal seems to be the most common material employed. Rock crystal sets were also exquisitely crafted status symbols; these crystal pieces are said to “count among some of the most beautiful pieces of lapidary work (gem and stone carving or polishing) to have survived from the medieval period.”[28] These pieces have historically been attributed largely to Fatimid Egypt, but recent scholarship asserts many of the crystalline pieces were likely crafted in Abbasid Baghdad or Khurasan[29]. Many of these pieces were preserved through being repurposed by European Christians for reliquaries.[30] Islamic chess pieces were known by Western Europeans who, through trade and warfare, by the eleventh century obtained pieces, of both ivory and crystal, and had created imitations from walrus tusk, bone, and deer antler. One famous set, the “Charlemagne Chessmen” which imitated Islamic technique with more figural representation, was stored in the reliquary of St. Denis until 1791.[31] Islamic empires like the Abbasid courts may have sent lavish chess sets crafted from rock crystal to Western polities as a subtle sign of cultural dominance[32]. Some pieces made from hardstones including banded agate, chalcedony, and jade have been found. The prevalence of these expensive and rare materials, which outnumber cheaper alternatives like wood and glass, supports the assertion that chess was an elite pastime, inaccessible to most outside of the ruling classes in the Islamic World.

[1] Freeman Fahid, Deborah. Chess and Other Games Pieces from Islamic Lands, London: Thames & Hudson, 2018.

[2] Murray, Harold James Ruthven. A History of Chess, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1962.

[3] Ahsan, Muhammad Manazir. Social Life Under the Abbasids. London; New York: Longman, 1979.

[4] Titley, Norah. Sports and Pastimes: Scenes from Turkish, Persian, and Mughal Paintings. London: British Library, 1979.

[5] Murray, History, 193.

[6] Ahsan, “Social Life,” 318.

[7] Remie Constable, Olivia. “Chess and Courtly Culture in Medieval Castile: The ‘Libro de ajedrez’ of Alfonso X, el Sabio.” Speculum 82, (April 2007): 301-347.

[8] Remie Constable, “Courtly Culture,” 314.

[9] Remie Constable, “Courtly Culture,” 309.

[10] Remie Constable, “Courtly Culture,” 302-303.

[11] Remie Constable, “Courtly Culture,” 305.

[12] Remie Constable, “Courtly Culture,” 311.

[13] Remie Constable, “Courtly Culture,” 318.

[14] Contandini, Anna. “Islamic Ivory Chess Pieces, Draughtsmen and Dice.” Oxford University Press, (January 1995): 111-130. https://www.academia.edu/44717636/Islamic_Ivory_Chess_Pieces_Draughtsmen_and ice

[15] Freeman Fahid, Deborah, Chess, 32.

[16] Freeman Fahid, Deborah, Chess, 24-25.

[17] Constandini, Anna, “Islamic Ivory,” 111.

[18] Freeman Fahid, Deborah, Chess, 68.

[19] Freeman Fahid, Deborah, Chess, 59.

[20] Murray, History, 187.

[21] Freeman Fahid, Deborah, Chess, 22.

[23] Freeman Fahid, Deborah, Chess, 63.

[24] Rosser-Owen, Mariam. “Chess and Other Games Pieces from Islamic Lands.” The Burlington Magazine 163, no. 1417, April 2021. https://www.burlington.org.uk/archive/book-review/chess-and-other-games-pieces-from islamic-lands-the-al-sabah-collection-dar-al-athar-al-islamiyyah

[25] Rosser-Owen, “Other Games,” 8.

[26] Freeman Fahid, Deborah, Chess, 63.

[27] Freeman Fahid, Deborah, Chess, 64.

[28] Rosser-Owen, “Other Games,” 22.

[29] Freeman Fahid, Deborah, Chess, 263.

[30] Rosser-Owen, “Other Games,” 1.

[31] Freeman Fahid, Deborah, Chess, 25.

[32] Freeman Fahid, Deborah, Chess, 65.

Bibliography

Ahsan, Muhammad Manazir. Social Life Under the Abbasids. London; New York: Longman, 1979.

Contandini, Anna. “Islamic Ivory Chess Pieces, Draughtsmen and Dice.” Oxford University Press, (January 1995): 111-130. https://www.academia.edu/44717636/Islamic_Ivory_Chess_Pieces_Draughtsmen_and ice

Freeman Fahid, Deborah. Chess and Other Games Pieces from Islamic Lands, London: Thames & Hudson, 2018.

Rosser-Owen, Mariam. “Chess and Other Games Pieces from Islamic Lands.” The Burlington Magazine 163, no. 1417, April 2021. https://www.burlington.org.uk/archive/book-review/chess-and-other-games-pieces-from islamic-lands-the-al-sabah-collection-dar-al-athar-al-islamiyyah