Extended Catalogue Entry

When analyzing the social structures and class structures of Safavid Iran and the Ottoman Empire, it is important to discuss the role of coffeehouses, particularly their role in simultaneously fostered freedom and enforced the hierarchal systems of the period. Coffeehouses began to appear in Safavid Iran and the Ottoman Empire in the late 16th century. The growing popularity of coffeehouses and coffee in the Safavid Empire was fostered by political stability, growing transportation infrastructure, and population growth1. However, in the Ottoman Empire, coffeehouses were often associated with disorder and dissent. Regardless, both Safavid and Ottoman coffeehouses were both bastions of intellectual and political rebellion, but also promoted participation in social hierarchy.

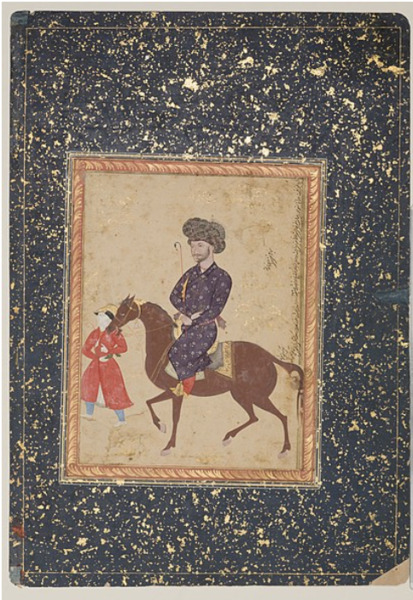

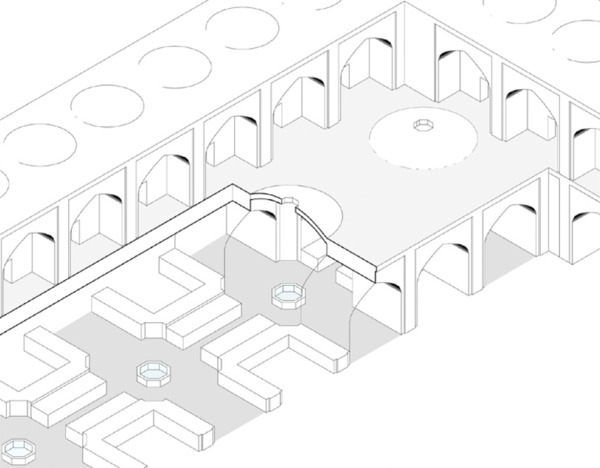

In “Album Page With An Equestrian Portrait of Mirza Muhammad Taqui Tabrizi”, a wealthy merchant is depicted travelling to a coffeehouse. In Safavid Iran, particularly Isfahan, coffeehouses were oriented along the public promenade in the center of the city known as the Charharbagh. Almost anyone could travel along the promenade and observe the things that took place in coffeehouses, since many of the activities took place in outdoor areas, visible to anyone walking the promenade. However, just because anyone could interact with the coffeehouse socially and economically does not mean that they all went about it in the same manner. The Charharbagh connected multiple neighborhoods of the city, particularly the Abbasbad, which was populated by wealthy merchant families2. Therefore, this promenade was often used as a means of flaunting one’s wealth, which is exactly what Mirza Muhammad Taqi Tabrizi is doing in this painting. The Charharbagh is particularly divided into a middle pathway, which is reserved for pedestrians, and the “lateral pathways” near the coffeehouses were reserved for those riding on horseback2. There were ponds separating the pedestrian path from the paths reserved for wealthier Safavid Iranians travelling on horseback2. In addition, the connected outdoor and indoor spaces allowed for the rich to flaunt their power in a public area. The overall structure of the Charharbagh serves as a method of maintaining the intricate class structure that existed in Safavid Iran. Coffeehouses along this promenade contributed to this hierarchy, and this painting is a representation of how wealthy Isfahanis flaunted their wealth.

It should be mentioned that the origin of coffeehouses and their rise to fame was due to their association with religious practices and the mosque3,6. This is despite the moral controversy it caused within Muslim communities, specifically regarding the leisure activities that occurred. Members of the religious class would often frequent and perform at coffeehouses, discussing matters of this world and the afterlife and performing poetry with other intellectuals. During the 16th to 17th centuries, there was also the rise of Sufism, a religious movement centered around spirituality and mysticism. This was reflected in the ritual coffee drinks that preceded meditations and prayers, specifically Sufi dhikrs3. Practices related to Sufism, particularly Sufi dhikrs, were limited to coffeehouses in Safavid Iran, this was not a practice in Ottoman coffeehouses3. While both Safavid and Ottoman coffeehouses served as bastions of intellectual dissent and leisure activity, Safavid Iranian coffeehouses promoted religious enlightenment and mysticism in a manner not observed in Ottoman coffeehouses.

This trend of coffeehouses being associated with religious and spiritual fulfillment was accelerated under Shah ‘Abbas II3. Initially coffeehouses, while associated with the upper classes, did not have the best reputations for intellectual fulfillment and morality, despite their initial association with religion. Due to its strong connections to Sufism and spiritual rituals, it is reasonable to refer to the institution of the Safavid Iranian coffeehouse as an extension of the mosque instead of a substitution.

In Safavid Iran, coffeehouses were not just a masculine space. In the early 1600s, Shah ‘Abbas ordered that on Wednesdays the women that were part of the court could frequent the promenade and attend coffeehouses2. This was not restricted to women of the higher classes either, many classes of women were permitted to mingle along the Charharbagh. However, women were still segregated entirely from men along the promenade and in the coffeehouses. This reflects the contradictory way in which coffeehouses functioned. They served as locations in which people of different socioeconomic classes could interact, yet there was a clear divide between these groups that was enforced by the architecture, and the law. In addition, there were often coffeehouse spaces that were relegated to professions, guilds, or classes of society, and as coffee got less expensive throughout the Safavid Empire, a higher number of community members started attending. In other words, everyone could participate, but they had to exist in their own confined space3. The coffeehouse was also the only public place in which one could respectably enjoy themselves without supposedly engaging in debaucherous activities associated with the “lower classes”3. Similar to Ottoman coffeehouses, there was also an abundance of political criticism of the Safavid Iranian government3. However, the political dissidence in Ottoman coffeehouses was treated much differently, and the class structure of Ottoman society was a bit different.

Ottoman society was mainly separated into the “ruling” and the “ruled5.” The ruling classes were made up of bureaucrats, administrators, janissaries, and theological professors5. Essentially government and religious officials and soldiers. The ruled class was made up of merchants, peasants and artisans5. This is interesting, given that the Mirza Muhammad Taqi Tabrizi, the merchant depicted in the painting, was a wealthy merchant and part of a powerful family. In Ottoman society, it was possible to become a part of the ruling class even if you were not part of the ruling class to begin with. In addition, in contrast to Safavid Iran, the social class of the Ottoman citizen or resident was not defined by their lineage5. The mobile nature of the class structure in the Ottoman Empire during the 16th and 17th centuries, with peasants regularly attaining education and becoming members of the ruling class5. In addition to upward mobility, it was possible to have multiple jobs that bridged the ruling and ruled classes. For example, bureaucrats and janissaries would become merchants, and would use their previously attained influence to make money as merchants and influence the worker’s guilds5. It is precisely this class mobility that sets the stage for the disorder surrounding Ottoman coffeehouses.

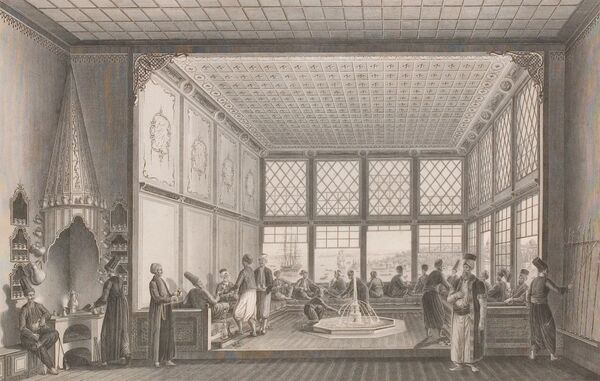

Many Ottoman officials had apparent moral concerns about coffee, tobacco, and coffeehouses, stating that it “has been the cause of various sorts of disobedience” and that it was fitne, or a political sedition4. Jurists issued fatwas or rulings against coffee6. These conservative jurists were often in competition with liberal jurists who thought that coffee was perfectly legall6. The Ottoman government eventually accepted the later decision6. Authors that opposed coffeehouses, coffee and tobacco and law enforcement joined forces to limit the impact that coffeehouses had4. This makes sense because along with the rise of the coffeehouse in the 16th and 17th centuries came a rise in socioeconomic mobility amongst the public, and the Ottoman state was particularly keen on enacting laws that were authoritarian in nature5. Some of the legislation that was utilized to maintain control were “exploiting representatives of authority” and illegal taxation of citizens5. This legislation, particularly strict laws against morally incorrect conduct and heavy taxation, were meant to combat the mobile class structure and the lack of rigidity surrounding social class. The Ottoman coffeehouse's sheer existence prevented this from occurring.

Safavid coffeehouses were oftentimes only accessible to the wealthy and the courtly classes, not even remotely connected to the poorer areas of the city, whereas Ottoman coffeehouses were both more accessible and more numerous4. Ottoman coffeehouses fostered more political dissent, and the association of tobacco and coffee with coffeehouses was used by the government to shut coffeehouses down4. This crackdown on public expression led to anti-ban authors responding to the moralists' arguments against coffeehouses. The moralists argued that the events that took place within the walls of the coffeehouses (smoking, coffee consumption, idleness etc.) went directly against sharia law. The anti-ban authors argued that the private sphere should limit public authority, and that there should be a legally neutral sphere4. The legally neutral sphere surrounding coffeehouse issues essentially meant that these issues were not to be judged harshly or affirmed4. This defense of the private community spaces that constituted coffeehouses influenced future policies and laws regulating or allowing public expression. All in all, the Safavid coffeehouses were remarkably uncontroversial in comparison to Ottoman coffeehouses, and the laws and discourse surrounding coffeehouses influence present-day discussions related to public expression.

1“Coffeehouse” Encyclopædia Iranica, online edition, New York, 1996-2023 https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/coffeehouse-qahva-kana#article-tags-overlay

2Emami, Fahsid. “Coffee Houses, Urban Spaces, and the Formation of A Public Sphere In Safavid Isfahan.” Muqarnas 33 (2016): 177–220. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26551685.

3Matthee, Rudi. “Coffee in Safavid Iran: Commerce and Consumption.” Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 37, no. 1 (1994): 1–32. https://doi.org/10.2307/3632568.

4Gürbüzel, Aslıhan. “Of Coffeehouse Saints: Contesting Surveillance in the Early Modern City.” In Taming the Messiah: The Formation of an Ottoman Political Public Sphere, 1600– 1700, 1st ed., 178–206. University of California Press, 2023. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv34j7mk1.11.

5Karababa, Emİnegül, and Gülİz Ger. “Early Modern Ottoman Coffeehouse Culture and the Formation of the Consumer Subject.” Journal of Consumer Research 37, no. 5 (2011): 742–760. https://doi.org/10.1086/656422.

6Arjomand, Saïd Amir. “Coffeehouses, Guilds and Oriental Despotism Government and Civil Society in Late 17th to Early 18th Century Istanbul and Isfahan, and as Seen from Paris and London.” In European Journal of Sociology / Archives Européennes de Sociologie / Europäisches Archiv Für Soziologie 45, no. 1 (2004): 23–42. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23998913.