Shadow Puppet Catalogue Entry

Shadow theaters have a long history across cultures, extending back to the ancient performance rituals they are derived from. Since before the common era, people have used fires to cast shadows on cave walls in religious or spiritual rituals. While no specific region or cultural group can be accredited with the creation of shadow plays, many scholars agree that the form originates from Asia, with evidence of early shadow plays from China, Indonesia, India, and Central Asia.[1]

Records of shadow plays within the Islamic world first originate from Egypt, where the first references of shadow play, referred to as khayal al-zill, date back to the twelfth century.[2] Egyptian shadow plays appear to have significant influence from Indonesian Javanese shadow theater, pictured to the left.[3] From Egypt, shadow plays spread throughout the Islamic world and were introduced to Turkey, likely following the Ottoman’s 1517 conquest of Egypt.[4]

The word khayal has origins and various other uses outside of shadow plays specifically, originally meaning “figure” or “phantom;” it comes to be associated with live theater and shadow plays specifically in the combined phrase khayal al-zill.[5] Some authors and historical sources have used khayal as a stand-in phrase for live theater performances, but it still remains distinct from khayal al-zill, which was used to refer to shadow plays in the Arabic world. These plays were different in form in that they follow the tradition of East Asian shadow puppetry and are only performed at night.[6]

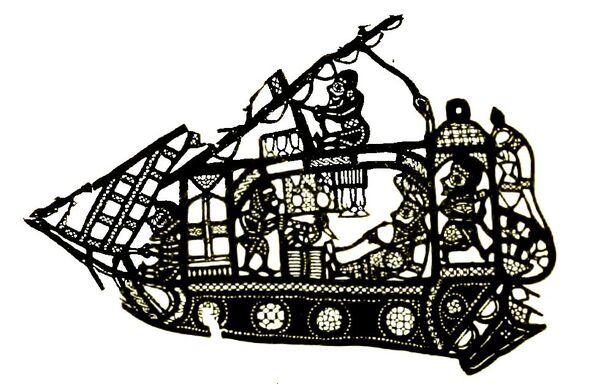

The shadow puppet of a battleship, pictured above, is one of around eighty puppets bought by German historian Paul Kahle in Menzaleh, Egypt, in 1909.[7] Kahle identifies these puppets as Mamluk in origin, dating their creation within the first half of the fourteenth century, making these puppets the oldest Islamic shadow puppets in existence.[8] These puppets were made by attaching thin sheets of leather animal skins together, stretching these skins to make them light in color and less opaque.[9] The puppet now appears to be black in color, this coating possibly existing due to paint, dirt, or soot covering the puppet as it has aged.[10] The puppet of a battleship, like the majority of the Menzaleh puppets, is over 60 centimeters long in size. It would have been brought to life by attaching sticks to jointed areas of the object, allowing it to move behind a backlit screen and participate in the action of a shadow play. [11]

The style of the Menzaleh shadow puppets has led many scholars to believe that they were produced in Mamluk Cairo. Stylistic similarities between these puppets include enlarged eye shape in human figures and repeat geometric patterns within internal spaces and around borders of the puppets.[12] These features are visible in the shadow puppet of musicians on an elephant, originating from the same group of Menzaleh puppets as the battleship puppet. Pictured on the right, the puppet of an elephant with musicians contains woven-like patterns also present in the puppet of a battleship. At the center of the elephant puppet is a circular blazon containing two parallel lines with a diamond inside. This has been identified as a possible personal emblem for an unidentified Mamluk Amir, and this specific blazon is consistently found throughout several Menzaleh puppets, suggesting that they were produced by the same craftsman over a relatively short period of time.[13]

Scholar Marcus Milwright argues for a later date attributed to the Menzaleh puppets than Kahle’s proposed dates of ca. 1290-1360.[14] The exact dating of these puppets is difficult to discern, although textual evidence does confirm the presence of shadow theater in Egypt from the eleventh century in the Fatimid era until the end of the Mamluk sultanate in 1517.[15] However, that does not necessarily indicate that the Menzaleh puppets were produced during the Mamluk period, as shadow plays continued in Egypt following its conquer by the Ottomans in 1517.[16]

The most notable discrepancy within the features of the puppets and their proposed date of origin within Mamluk Egypt presents itself in the Menzaleh puppet, pictured below, of a boat carrying sailors and an elite occupant, wearing the head garments of a high social class, who appears to be smoking from a water pipe.[17] Because tobacco was not introduced into the Islamic world until the seventeenth century and the water pipe depicted in the shadow puppet was not documented for use in smoking other substances such as opium or hashish prior to the seventeenth century, this puppet does not seem to fall within the origin dates of ca. 1290-1360, drawing into question the dates of the remaining Menzaleh puppets.[18] It is possible that the aspects of these puppets that point towards a more Mamluk rather than Ottoman cultural style, reflected within clothing and weapons, are more a reconstruction of the period rather than a reflection of the time in which the shadow puppets were constructed.

Accompanying the physical shadow puppets was the production of the shadow play itself, which often included music and a written script. The oldest extant shadow plays are attributed to Cairo author and oculist Ibn Daniyal, who lived in thirteenth century Mamluk Egypt.[19] Ibn Daniyal’s three surviving shadow plays center around crude subjects and serve as rare written examples of a larger oral storytelling tradition.[20] Ibn Daniyal’s plays were written to be performed by the puppet master as a one-man show, although the puppet master would also be accompanied by a troupe of musicians who would periodically join in along with his voice, maintaining that the audience still hears only one voice.[21] Because one actor, or puppet master, performed all of the parts within a play, he is required to play both male and female roles, acting across the two genders. Throughout different scenes in Ibn Daniyal’s plays, gender roles are both performed as expected within society and bent so that they go against the norm, likely intended for comedic effect. [22] Shadow theater, and the plays of Ibn Daniyal in particular, was considered somewhat controversial and often associated with lowbrow comedy catering to common people.[23] Shadow plays allowed for storytelling focusing on more mundane aspects of life, often also incorporating erotic or sexual scenes.[24] However, it is also documented to have been performed at princely parties as a source of comedic entertainment.[25] Even sultans enjoyed these performances, notably Sultan Selim I of the Turkish Ottomans, who saw a play re-enacting the hanging of the last Mamluk sultan with Ottoman gain of the territory in 1517.[26]

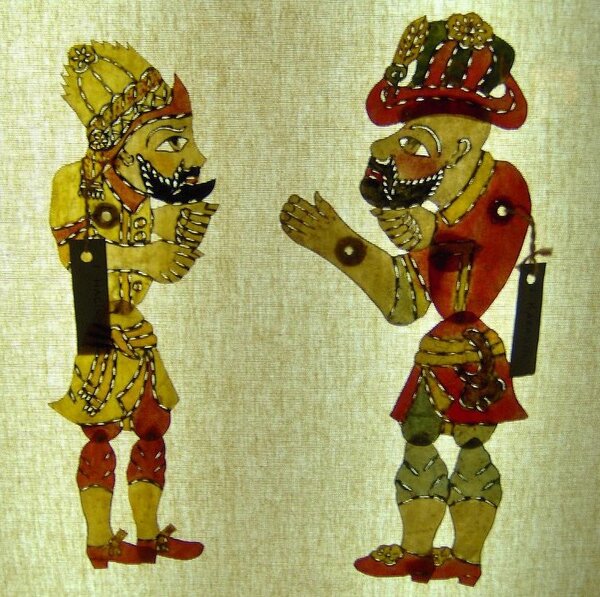

From the fall of Mamluk Egypt, the popularity of shadow theater spread to Ottoman Turkey, where shadow plays evolved to take on new forms. Like Egyptian shadow theater, it is a one-man show in which shadow puppets are projected from behind a lit screen in the nighttime.[27] Turkish shadow plays are commonly known as Kargöz plays, centering mainly on the two characters of Kargöz and Hajivat; Kargöz serves as a caricature of undesirable traits, while Hajivat is a personification of a respectable community member.[28] These two characters, seen in the image to the left, are constant in every Turkish shadow play, always appearing within the same color schemes, much more vividly colored than the older Menzaleh puppets.[29] Like previous Egyptian shadow plays, Ottoman era shadow theater ca. 1605 centered around performances in public, urban spaces, such as coffee houses or smokers dens.[30]

Shadow theater provided for a valuable means for common people within Islamic civilizations to participate in storytelling traditions. Shadow puppets serve as a record of leisurely life within Islamic territories in both Egypt and Syria, combining Islamic visual culture and artistic styles with their purpose to provide entertainment and a way for people to participate in the greater narrative of their civilization.

[1] Fan Pen Chen, “Shadow Theaters of the World,” Asian Folklore Studies 62, no. 1 (2003): 26-27. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1179080.

[2] Chen, “Shadow Theaters of the World,” 37.

[3] Chen, “Shadow Theaters of the World,” 37-38.

[4] Andreas Tietze, The Turkish Shadow Theater and the Puppet Collection of the L.A. Mayer

Memorial Foundation (Berlin: Mann, 1977), 16-17.

[5] Shmuel Moreh, Live Theatre and Dramatic Literature in the Medieval Arab World (New York:

New York University Press, 1992), 123-125.

[6] Moreh, Live Theatre, 126-127.

[7] Alain F. George, “The Illustration of the ‘Maqāmāt’ and the Shadow Play,” Muqarnas 28,

(2011): 4. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23350282.

[8] Paul Kahle, “The Arabic Shadow Play in Egypt,” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great

Britain and Ireland, no. 1 (January 1940): 22. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25221591.

[9] Marcus Milwright, “On the Date of Paul Kahle’s Egyptian Shadow Puppets,” Muqarnas 28,

(2011): 44. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23350283.

[10] Milwright, “On the Date,” 44.

[11] George, “Illustration of Shadow Play,” 4.

[12] Milwright, “On the Date,” 52

[13] Milwright, “On the Date,” 49-52.

[14] Milwright, “On the Date,” 43.

[15] Milwright, “On the Date,” 49.

[16] Moreh, Live Theatre, 126.

[17] Milwright, “On the Date,” 52-54.

[18] Milwright, “On the Date,” 54-57.

[19] Kahle, “Arabic Shadow,” 22.

[20] George, “Illustration of Shadow Play,” 3.

[21] Li Guo, “Cross-Gender ‘Acting’ and Gender-Bending Rhetoric at a Princely Party: Performing

Shadow Plays in Mamluk Cairo,” In In the Presence of Power: Court and Performance

in the Pre-modern Middle East, edited by Evelyn Birge Vitz and Maurice A. Pomerantz,

164-178, (New York: New York University Press, 2017), 168-169.

[22] Guo, “Performing Shadow Plays,” 169-172.

[23] Guo, “Performing Shadow Plays,” 164.

[24] George, “Illustration of Shadow Play,” 5.

[25] Guo, “Performing Shadow Plays,” 173.

Bibliography

Chen, Fan Pen. “Shadow Theaters of the World.” Asian Folklore Studies 62, no. 1 (2003): 25-64.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/1179080.

George, Alain F. “The Illustration of the ‘Maqāmāt’ and the Shadow Play.” Muqarnas 28,

(2011): 1-42. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23350282.

Guo, Li. “Cross-Gender ‘Acting’ and Gender-Bending Rhetoric at a Princely Party: Performing

Shadow Plays in Mamluk Cairo.” In In the Presence of Power: Court and Performance

in the Pre-modern Middle East, edited by Evelyn Birge Vitz and Maurice A. Pomerantz,

164-178. New York: New York University Press, 2017.

Kahle, Paul. “The Arabic Shadow Play in Egypt.” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great

Britain and Ireland, no. 1 (January 1940): 21-34. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25221591.

Milright, Marcus. “On the Date of Paul Kahle’s Egyptian Shadow Puppets.” Muqarnas 28,

(2011): 43-68. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23350283.

Moreh, Shmuel. Live Theatre and Dramatic Literature in the Medieval Arab World. New York:

New York University Press, 1992.

Tietze, Andreas. The Turkish Shadow Theater and the Puppet Collection of the L.A. Mayer

Memorial Foundation. Berlin: Mann, 1977.