Extended Catalogue Entry

Coffee has long been acknowledged as a social beverage. Dating back to the mid-sixteenth century, when a Yemeni trader first introduced coffee to the Ottoman Empire, coffee’s integration into society has only become more deeply rooted.[1] When coffee was introduced, the Ottoman Sultan, accompanying elites, and commoners were all wary of this new bitter item of consumption, causing attempted bans by Sultans. Nevertheless, coffee persisted, infiltrating all domains of life. The tasty and addicting beverage seeped through social, cultural, political, economic, public, and private spheres, proving to be an integral part of Ottoman culture.

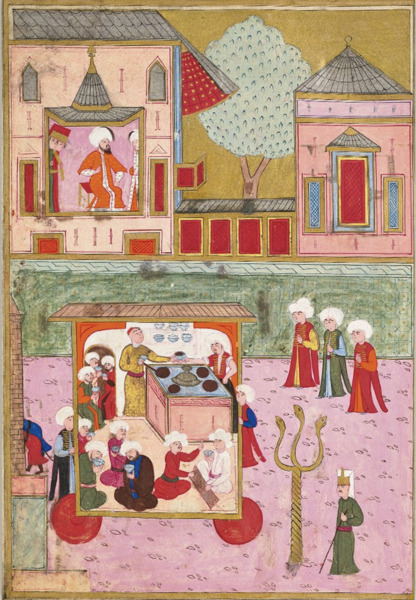

Accordingly, coffee was present in several imperial ceremonies and social events, and the Ottoman circumcision ceremonies were no exception. Effectively, coffee was featured in the Imperial Circumcision Ceremony of 1582, as illustrated in the piece “Procession of coffee sellers with a model of the coffee cart during the Imperial circumcision festival” by Nakkaş Osman featured in the Surname-i Hümayun an album of manuscripts depicting Ottoman Empire ceremonies through both pictorial and accompanied textual descriptions. As the title suggests, the piece commemorates coffee sellers modeling coffee carts containing their delectable coffee and parading through the Hippodrome. As such, the work is the perfect example to study the significance of coffee as a substance of consumption in the empire’s successful attempt to combine social institutes and ceremonial significance with leisure.

While coffee initially emerged as a luxury item, alongside many others like tobacco, only available to the wealthy and elite, coffee began spreading through various social sectors.[2] Coffeehouses promoted the leaking of coffee from the highest to the lowest class. Coffeehouses were open to all members of society and frequented by people from all walks of life, including merchants, artisans, and common laborers. Therefore, coffeehouses were vital social institutions in all Ottoman cities, especially Istanbul, where individuals could drink coffee, play games, and engage in intellectual discourse. “A Turkish Coffee-House, Constantinople” by Amadeo Preziosi, a Maltese painter who painted various aspects of Ottoman life, perfectly encapsulates the crowded, sociable, and varying spaces that Ottoman coffeehouses were meant to represent. Coffeehouses took the relaxing activity of sipping on freshly brewed coffee and built on it, placing it in a social setting, inevitably equating coffeehouses and coffee with leisure for the Ottomans. The association of coffee and relaxation was not just true for the Ottomans. Other empires, like the Safavid Dynasty that ruled over what is now modern-day Iran, also participated in drinking coffee as a leisurely activity.[3] The remnants of coffeehouses in Maydan-i Naqsh-i Jahan and Khiyaban-i Chaharbagh in an accessible fashion to the general public indicate that coffee and coffeehouses had similar functions as social institutes as has been pictured in “Convivial meeting of Kai Khosrow” by Hossein Qollar-Aqasi.[4]

As the tie between coffeehouses and coffee with leisure grew more powerful, Sultan Murad III’s worries concerning the vast spread of the new beverage also grew more powerful. His concern grew so robust that in 1585, he prohibited the consumption and sale of coffee throughout the Ottoman Empire. The reasons behind his worry are largely unknown; however, several accounts suggest that the ban was due to suspicions regarding political discourse and complaints in coffeehouses as well as coffee as a stimulant drug. As coffee became more widespread, it became more widely known that coffee helped individuals stay awake. This mysterious nature of coffee as a stimulant drug perplexed Sultan Murad III, resulting in anger towards the beverage and violent repercussions for those who did not follow his banning orders. To much of his dismay, coffee had become too integrated into the Ottoman Empire, and reinforcing the ban became harder and harder. Sultan Murad III was aware of the flourishing economy due to coffeehouses and coffee sales and began to be lenient, permitting the beverage to continue its spread throughout the empire.[5]

Moreover, Sultan Murad III could have even developed a liking towards the bitter beverage since he was a patron of arts and sciences, both of which were frequent topics of discourse in coffeehouses. The theory of Sultan Murad III enjoying the leisurely activity of sipping freshly brewed coffee could be fathomable as during his son’s circumcision ceremony, he permitted coffee sellers to parade through the Hippodrome as is presented through “Procession of coffee sellers with a model of coffee cart during the Imperial circumcision festival.” Accounts indicate that the Sultan enjoyed the drunken humorous coffee procession so much that he promised the sellers a hiatus from his wrath.[6] Permitting an Ottoman leisurely activity such as drinking coffee in the Sultan’s grand forum and lavish celebrations like the Circumcision Ceremony of 1582 successfully merged leisure into important imperial ceremonies. In addition to coffee, the Circumcision Ceremony consisted of dancers, humorous acts, mock battles, and more, unmistakably endeavoring to incorporate everyone from the empire to put the empire’s social hierarchy on display, presenting the empire as a unified front. The fact that coffee was one of the main components at the forefront of this act signifies coffee was a vital leisurely act in the Ottoman Empire, as well as a symbol of the unity of the empire.

As aforementioned, coffee’s role as a social refreshment promoted leisure in prominent imperial ceremonies hosted by the Sultan, like the Circumcision Ceremony of 1582 hosted by Sultan Murad III for his son Prince Mehmed. Ottoman circumcision ceremonies were significant events in young imperial princes’ lives. Circumcision, both in the Islamic culture and in the context of these ceremonies, culturally represents a boy’s transition from childhood to adulthood. For the Ottomans, these ceremonies described just that and a scheme to exhibit hierarchy in the empire and the socialization and integration of all peoples. The circumcision ceremonies were typically held from 10 to 15 days; however, some circumcision ceremonies lasted from 50 to 55 days. The Circumcision ceremony of 1582 was held for over 50 days, making it the most expensive and grand circumcision ceremony the Ottoman Empire carried out.[7] Manuscripts depicting other circumcision ceremonies the Ottomans held prove this. “Köçek Troupe at a Fair'' portrays the Circumcision Ceremony of 1720 held by Sultan Ahmed III for his sons Süleyman, Mehmed, Mustafa, and Bayezid.[8]The Circumcision Ceremony of 1720 only lasted 21 days, as opposed to Sultan Murad III’s ceremony of 1582, which was more than twice as long. Comparing the Circumcision Ceremony of 1582 to others during the empire’s rule allows a proper comparison of the ritual’s grand nature.

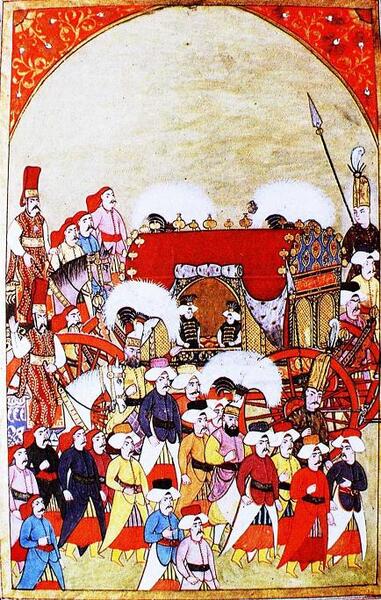

Since the Circumcision Ceremony of 1582 was the most glorious ceremony the Ottomans held, Sultan Murad III ensured to fill each of the 50 days with intriguing processions, races, and activities for those of all social classes to participate in, including the parade and distribution of coffee as is seen through “Procession of coffee sellers with a model of coffee cart during the Imperial circumcision festival.” In preparation for the circumcision ceremony, surgeons would typically circumcise young boys of all social classes throughout the days leading up to the ceremony’s climax. The imperial prince or princes that would be circumcised would be driven in a carriage on one of the last days of the ceremony. An example of this carriage procession is shown in “Princes Mustafa and Mehmed driven to Topkapi Palace to be circumcised,” found in Surname-i Vehbi. During the circumcision ceremonies, the imperial princes were typically taken to unique circumcision tents or buildings in essential places like the Topkapi Palace, where the best surgeon met the young boys. The areas where the circumcision occurred were typically mounted with sound-producing features like the musical fountains that were mounted outside the Topkapi Palace circumcision room to keep the prince’s cries from seeping out. Following the circumcision, the princes were bestowed with a multitude of gifts.

The integration of coffee in momentous imperial festivities like the Circumcision Ceremonies heightened the spread of coffee not only in the Ottoman Empire but also throughout the rest of the world. The integration of coffee and social institutions like coffeehouses that came with the beverage had a transformative nature. Coffeehouses permitted discourse on any subject matter, be it cultural, social, political, or economic. Discourse provoked transformation and progression in societies, be it minute or large-scale. The integration of all social classes in the public sphere, both through coffee houses and imperial ceremonies, was a transformation and change from previous empires that kept classes segregated. Hence, coffee was simply an instigator that provoked transformation. It is arguable that the transformative nature of coffee still exists in our present-day world in the regions that the Ottomans occupied and everywhere else (Dinçer, Evren M., and Ayşe Özçelik).[9] Through the comparison of Ottoman coffeehouses and modern coffee shops, the similarities are evident.The modern coffee shop mimics socialization and discourse that transpired dating back to the 16th-century Ottoman coffeehouses. Modern-day coffee shops still provide social spaces for all social classes where discourse about sociocultural, political, or economic topics can occur, suggesting that coffee had and still has a transformative nature globally that was blossoming in its origins in the Ottoman Empire.

[1] Neha Vermani, “Early Modern Coffee Culture and History in the Islamic World,” Folger Shakespeare Library, May 14, 2021, https://www.folger.edu/blogs/shakespeare-and-beyond/islamic-history-of-coffee/.

[2] Tülay Artan, Aspects of the Ottoman Elite's Food Consumption: Looking for ‘Staples," ‘Luxuries," and ‘Delicacies’ in a Changing Century (New York: State University of New York Press, 2000), 107-200, Google Books.

[3] Farshid Emami, “Coffee Houses, Urban Spaces, and the Formation of a Public Sphere in Safavid Isfahan.,” Muqarnas 33, no. 1 (2016): 177–220. https://doi.org/10.1163/22118993_03301p008.

[4] Rudi Matthee, Coffee in Safavid Iran: Commerce and Consumption (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2005), 144-74.

[5] Savaş Ay and Yavaş Fatih, Istanbul'un Kahvehanelerinden: From the Coffee Houses in Istanbul (Turkey: İstanbul Büyükşehir Belediyesi Kültür A.Ş. Yayınları, 2012).

[6] Derin Terzioğlu, “The Imperial Circumcision Festival of 1582: An Interpretation,” Muqarnas 12 (1995): 84–100. https://doi.org/10.2307/1523225.

[7] Terzioğlu, “Circumcision Festival,” 85.

[8] Sinem Erdoğan İşkorkutan, The 1720 Imperial Circumcision Celebrations in Istanbul: Festivity and Representation in the Early Eighteenth Century, (Brill 2020).

[9] Evren M. Dinçer and Ayşe Özçelik, “Chasing Coffee: A New Research Agenda in Turkey,” Society 57, no. 2 (June 2, 2020): 323–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12115-020-00486-3.

Works Cited

Artan, Tülay. “Aspects of the Ottoman Elite's Food Consumption: Looking for ‘Staples," ‘Luxuries," and ‘Delicacies’ in a Changing Century.” In Consumption Studies and the History of the Ottoman Empire, 1550-1922: An Introduction, edited by Donald Quataert, 107–200. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press, 2000.

Ay, Savaş and Fatih Yavaş. Kahvehanelerinden, Istanbul’Un: From the Coffeehouses in Istanbul. Edited by Sabri Dereli, Ahmet Yaşar, and Ömer Osmanoğlu. Translated by İdil Çetin, Can Denizer and A. Altay Ünaltay. İstanbul, Turkey: İstanbul Büyükşehir Belediyesi Kültür A.Ş. Yayınları, 2012.

Dinçer, Evren M. and Ayşe Özçelik. “Chasing Coffee: A New Research Agenda in Turkey.” Society 57, no. 2 (June 2, 2020): 323–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12115-020-00486-3.

Emami, Farshid. “Coffee Houses, Urban Spaces, and the Formation of a Public Sphere in Safavid Isfahan.” Muqarnas 33, no. 1 (2016): 177–220. https://doi.org/10.1163/22118993_03301p008.

İşkorkutan, Sinem Erdoğan. The 1720 Imperial Circumcision Celebrations in Istanbul: Festivity and Representation in the Early Eighteenth Century. Boston: Brill, 2021.

Matthee, Rudi. In The Pursuit of Pleasure: Drugs and Stimulants in Iranian History 1500-1900. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2005.

Şahin, Kaya. “Staging an Empire: An Ottoman Circumcision Ceremony as Cultural Performance.” The American Historical Review 123, no. 2 (April 2018): 463–92.

Terzioğlu, Derin. “The Imperial Circumcision Festival of 1582: An Interpretation.” Muqarnas 12 (1995): 84–100. https://doi.org/10.2307/1523225.

Vermani, Neha. “Early Modern Coffee Culture and History in the Islamic World.” Folger Shakespeare Library , May 14, 2021. Accessed May 1, 2023. https://www.folger.edu/blogs/shakespeare-and-beyond/islamic-history-of-coffee/.