Woven Tapestry Fragment Catalogue Entry

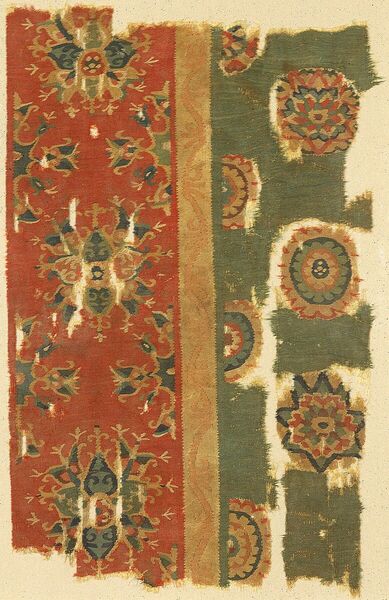

This intricate woven tapestry fragment is a textile from the middle of the eighth century CE, during a period of early Islamic expansion of the Umayyad dynasty under the rule of the caliph Marwan II[1]. The fragment resembles a garden of Paradise because of the staggered rosettes and floral medallions that emerge from the green, grass-like background[2]. It measures 12 by 18.75 inches and features quadriform ornamental elements, which are typical of Sasanian ornamental design[3]. The lack of a completed edge on the fragment suggests that it was likely formerly a part of a bigger cloth. Popular Umayyad places such as Qusayr ‘Amra and Khirbat al-Mafjar house mosaics which contain hints of similar textiles, suggesting that the tapestry fragment may have originally existed as a wall furnishing or a wool seat[4]. Still, other sources point to alternative uses for the fragment as well as unique interpretations of its ornamental design and composition.

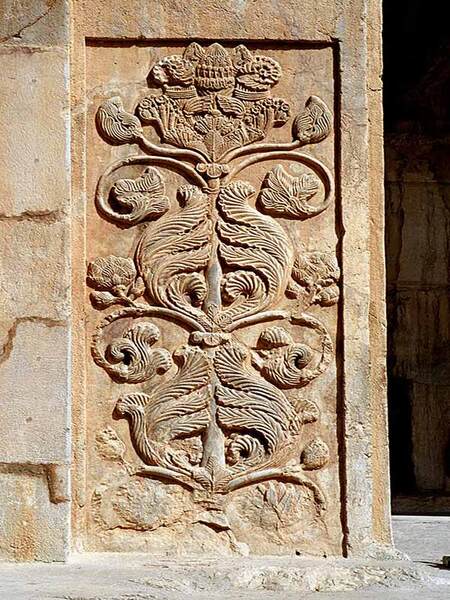

The tapestry fragment was created using Sasanian weavers' unique S-spun wool weaving technique[5]. When examined more closely, the tapestry fragment's pattern may have previously contained a series of parallel bands, or the green section with rosettes may have been a portion of a field-like design, with the surrounding red design serving as the border[6]. The notion that this piece was most likely a part of a carpet or furnishing textile and that it was intended to depict a garden similar to that of Paradise is supported by this description of what the original fragment may have looked like. Staggered rows of rosettes which is repeated across the entire fabric is also seen on the Tree of Life carving at Taq-i Bustan, a Sasanian monument from the late sixth or early seventh century[7]. Similar fragments were largely imported in the early Tang dynasty from the Iranian world. The exchange of goods with Sasanian and similar medieval ornamental designs conveyed a message of cross-continental prestige and adoption of new meanings for certain artwork and fragments. This is also seen with the use of Sasanian ornament in the mosaic of the inner narthex at Hagia Sophia[8]. The use of Sasanian design across different dynasties conveys a leisurely component in that fragments with niche designs and patterns were reinterpreted by different people in later times. Therefore, this fragment may have been used by commonfolk in the Umayyad period as a carpet or furnishing textile, and it could have also been used as part of a quilt or a robe by those in a different period[9].

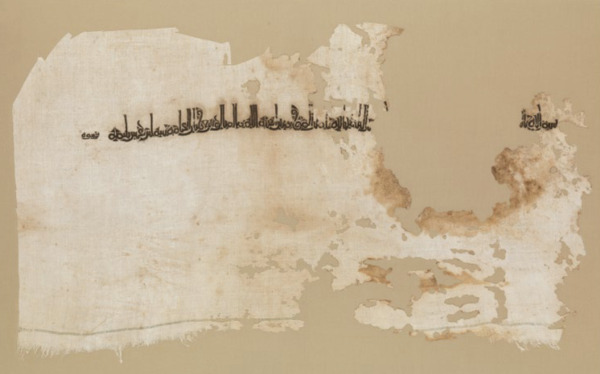

The materials wool, linen, mohair, and cotton were attributed to commonfolk and their everyday practices. The particular weaving techniques, colors, designs, and cuts of such fabrics told the stories of people’s identity, profession, wealth, morals, and more. The stages of the creation of textiles range from the work of shepherds, shearers, winders, spinners, dyers, weavers, finishers, and tailors, and each step in the process illustrates the dedication to this art form as a display of culture, leisure, and religious expression[10]. Knowing that this tapestry fragment was likely a furnishing textile, it may have been used in carpets of civilian homes or in houses of prayer[11]. This points to the utilization of wool tapestry fabrics to decorate leisurely areas during the early Islamic expansion period. Other materials were also quite prevalent in the period of early Islamic expansion. In addition to wool and linens, silk and gold thread were used to createtapestries, clothing, robes, tiraz, and more during the Umayyad period. Some fragments made from silk were used in robes to show status, while others made from wool and tiraz were particularly used in clothing, carpets, furnishing textiles, and more[12]. Such fragments were likely present in both formal and leisurely activities, from clothing worn to meet with Umayyad leaders like caliph Marwan II to sitting on furnished seats and enjoying coffee in Egypt, Iran, or Iraq with fellow civilians. Moving further with the idea of the tapestry fragment as a furnishing textile, the built spaces where the fragment may have appeared were likely living spaces where leisurely activities such as lounging, socializing, reflecting, and more were conducted[13].

The artistic elements and construction of the woven tapestry fragment suggest deeper meanings of its intended purpose. As mentioned previously, the fragment features staggered rosettes and floral medallions emerging from a green background, giving the impression of a garden of Paradise[14]. There is a supporting interpretation of the fragment, which refers to the decoration of it as a mobile garden, which, once spread by the user, gave the impression that it was a miniature rendition of Paradise and reminded those who sat on it or observed it of the beauty of its landscape. Through its floral motifs and elaborate rosettes, this fragment represents a leisurely element that art brings individuals through an act of observation and reflection - an element that is incorporated into this piece from the Paradise-like background and vibrant colors utilized throughout the textile[15]. As a result, a representation of a garden of Paradise would have significant religious and spiritual significance to the Muslim viewers of the fragment, who valued gardens and nature as a reflection of God's beauty and generosity.

Despite the fragment's beauty and historical significance, the maker of the tapestry fragment is unknown. Yet, the fact that a portion of it has survived and been preserved is a testament to the skill and artistry of Umayyad weavers during the early period of the dynasty as well as the skills of those who used it in later periods[16]. The production of this tapestry fragment required a high level of skill and craftsmanship. The weavers had to carefully choose the colors and threads to create the intricate floral pattern. Using the S-spun weaving technique also required the weavers to have great experience and expertise in order to create a distinctive design that is characteristic of early Islamic textiles and specifically textiles of the Umayyad period[17]. Inspired by Sasanian weaving techniques, the creators of this fragment adopted a tradition of learning from and teaching others, and of course, creating textiles, which emphasize leisurely activities in the lives of Umayyad artists.

My group’s topic for the exhibit assignment was textiles. My object is from the Umayyad period, which was a time of great artistic and cultural achievement in Islamic history, and textiles played an important role in the decoration of these spaces. Textiles speak to variety of purposes, uses, and reuses over time. I chose to study a woven tapestry fragment, which was a textile most likely used as a furnishing fabric or carpet in common built spaces of the Umayyad period such as a mosque or home. Understanding the nomadic lifestyles of the early Islamic people, textiles like this were likely used for other purposes after it was initially used. For instance, woven carpets were used to make travelling bags which were carried by pack animals. They were also used to make tents, serve as a partition between rooms, decorate entrances, make couches, put over divans, and more[18]. My textile has likely been used for diverse purposes after its intended use as a furnishing fabric. Due to its thick wool texture, it is expected for its original fabric to be repurposed and adapted for different uses over time by different types of people.

This woven tapestry fragment relates to the theme of “leisure” because of its original context of utilization as a furnishing textile. Textiles such as the tapestry fragment played a significant role in early Islamic leisure as they were used to decorate both imperial and ordinary spaces. Textiles were one of the most prestigious art forms of the time, holding great value and honor, and were used to express identity and religious expression[19]. The use of this textile for its intended purpose as a furnishing fabric or carpet supports a leisurely component due to the fact that its Paradise-like composition encouraged observation and reflection, both of which are habitual and frequent activities. Even now, to viewers seeing it in a museum setting, the textile provokes thought, curiosity, and reflection, which further promotes the theme. As mentioned previously, this fragment was reinterpreted across time and each of its possible “newer” uses also convey elements of leisure. Similar fragments were used for a multitude of purposes including for wall decoration, to partition rooms, close off private spaces, decorate entrances, and to put over couches[20]. Aside from its use in built spaces, it could also have been used in a robe, quilt, as a travelling bag, or tent[21]. All of these diverse uses point to this textile as a leisurely fabric used by commonfolk for common purposes. The theme of leisure is emphasized not only in the fragment’s original context, but also in its later usage and present day. The inclusion and utilization of this tapestry fragment in various spaces for a multitude of reasons inform us about the lifestyles and values of people from different periods. Its use in leisurely spaces serves as a means of observing beauty in common areas and endeavors. Ultimately, this tapestry fragment is an important artifact of early Umayyad art that provides insights into the religious, cultural, and artistic achievements of early Islamic societies.

Works Cited

Canepa, Matthew P. "Ornament, Display, and Cross-Continental Power and Prestige." In "Distant Displays of Power: Understanding Cross-Cultural Interaction Among the Elites of Rome, Sasanian Iran, and Sui-Tang China," edited by Matthew P. Canepa. Special issues, Ars Orientalis 38 (2010): 121-154.

Denny, Walter B. “Carpets, Textiles, and Trade in the Early Modern Islamic World.” In Companion to Islamic Art and Architecture Volume II: From the Mongols to Modernism, edited by Finbarr Flood and Gulru Necipoglu, 972-95. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119069218.ch37.

Hillenbrand, Robert. Islamic Art and Architecture. New York: Thames and Hudson, 1999.

Mozzati, Luca. Islamic Art: Architecture, painting, Calligraphy, Ceramics, Glass, Carpets. New York: Prestel, 2010.

Sokoly, Jochen. “Textiles and Identity.” In Companion to Islamic Art and Architecture Volume I: From the Prophet to the Mongols, edited by Finbarr Flood and Gulru Necipoglu, 275-99. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119069218.ch11.

Teece, Denise-Marie. “Woven Tapestry Fragment.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Accessed April 5th, 2023. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/451019.

Walker, Daniel. “Islamic.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 53, no. 3 (1995): 28-34. https://doi.org/10.2307/3258788.

Williams, Elizabeth Dospel. “A Taste for Textiles: Designing Umayyad and Early ʿAbbāsid Interiors.” Dumbarton Oaks Papers 73 (2019): 409–32.

Wu, Sylvia. “Textile as Portable Garden,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art. November 17, 2015. https://www.metmuseum.org/blogs/ruminations/2015/textile-as-portable-garden. Accessed on March 25th, 2023.

[1] Denise-Marie Teece, “Woven Tapestry Fragment,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, accessed April 5th, 2023. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/451019.

[2] Daniel Walker, “Islamic,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 53, no. 3 (1995): 28-34.

[3] Matthew Canepa, “Ornament, Display, and Cross-Continental Power and Prestige." In "Distant Displays of Power: Understanding Cross-Cultural Interaction Among the Elites of Rome, Sasanian Iran, and Sui-Tang China,” Ars Orientalis 38, (2010): 121-154.

[4] Sylvia Wu, “Textile as Portable Garden,” accessed March 25th, 2023, https://www.metmuseum.org/blogs/ruminations/2015/textile-as-portable-garden.

[5] Teece, “Woven Tapestry Fragment.”

[6] Walker, “Islamic,” 28-34.

[7] Walker, “Islamic,” 28-34

[8] Canepa, “Ornament,” 138.

[9] Canepa, “Ornament,” 121-154.

[10] Walter B. Denny, “Carpets, Textiles, and Trade in the Early Modern Islamic World.” In Companion to Islamic Art and Architecture Volume II: From the Mongols to Modernism, , ed. Finbarr Flood and Gulru Necipoglu (Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, 2017), 972-995.

[11] Denny, “Carpets,” 972-995.

[12] Jochen Sokoly, “Textiles and Identity.” In Companion to Islamic Art and Architecture Volume I: From the Prophet to the Mongols, ed. Finbarr Flood and Gulru Necipoglu (Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, 2017), 275-299.

[13] Elizabeth Dospel Williams, “A Taste for Textiles: Designing Umayyad and Early ʿAbbāsid Interiors,” Dumbarton Oaks Papers 73, (2019): 409–432

[14] Walker, “Islamic,” 28-34.

[15] Wu, “Portable Garden.”

[16] Walker, “Islamic,” 28-34.

[17] Teece, “Woven Tapestry Fragment.”

[18] Luca Mozzati, Islamic Art: Architecture, painting, Calligraphy, Ceramics, Glass, Carpets (New York: Prestel, 2010).

[19] Mozzati, Islamic Art.

[20] Robert Hillenbrand, Islamic Art and Architecture (New York: Thames and Hudson, 1999).

[21] Mozzati, Islamic Art.