Ottoman Wrestling Catalogue Entry

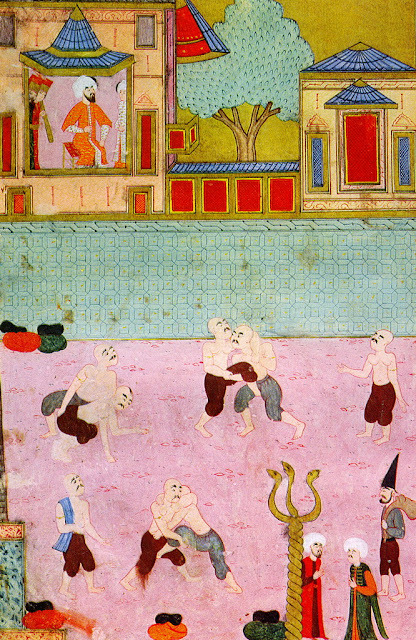

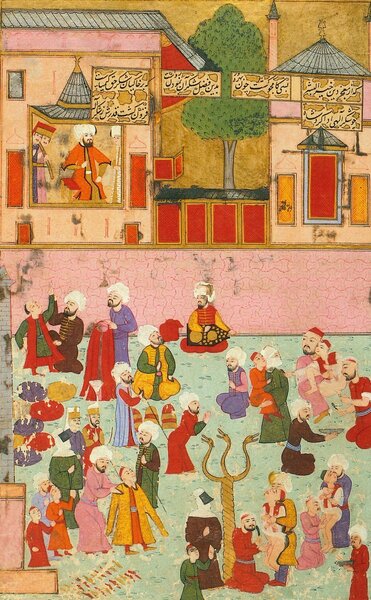

Nakkas Osman’s painting portrays early modern dramatic entertainment in the Ottoman Empire. It is displayed in a manuscript dedicated to the circumcision ceremonies of Ottoman princes in the 16th century. The Ottoman Sultan at the time, Sultan Murad deemed the ceremony as important as a military campaign, largely because it was a distraction during a large financial crisis at the time. The festival was meant to distract the population by displaying the Ottomans’ imperial generosity and power[1]. The portrait shows the 1582 festivities with shirtless men wrestling in a public space amongst many men dressed in elite clothing. The upper half section of the painting shows the Sultan overseeing the match with a young boy on the side, potentially Prince Mehmed, the celebrated son. The lower half shows muscular men wrestling in pairs with different techniques and others engaged in conversation. Those in conversation are wearing different clothing, leading to the possibility of these being foreign envoys from different states at the public event. During these circumcision ceremonies, Ottomans would show off their skills and wrestle each other in front of opposing envoys in an attempt to intimidate them with mock battles or to show off their skills to attendees of these festivities. The painting provides a glimpse of the Ottoman sports culture during this period.

In 1582, the circumcision of Prince Mehmed was celebrated for over fifty days, being the longest festival held by the Ottomans.[2] The traditional and cultural Islamic ceremony marks a transition from childhood to adulthood and was an important social event that brought thousands of people including the elite of the Ottoman Empire together[3]. Circumcision was also seen as a way of asserting social status by showing off wealth and power[4]. During these festivals hosted by Ottoman sultans, several hundred performers would entertain the sultan, and sports, games, and competitions would fill the courtyards[5]. One of the most important aspects of these festivities was wrestling, an essential part of Ottoman culture. This was one of the most popular sports practiced in the Ottoman Empire and was also a form of entertainment for all ages and social classes[6]. The Ottomans believed the activity promoted good character and was highly respected by society. It was considered a symbol of masculine strength and mental agility[7].

While wrestling was considered to signify good character and skills, it also was used as a diplomatic gesture to attendees. This could be seen in a positive manner, as wrestling was seen as essential to Ottoman identity and culture and could be used to maintain strong diplomatic ties with other empires by showing off their skills and strength. However, it can also be seen in an intimidating manner to assert cultural dominance over rivals, such as the Safavids of Iran. Both were two of the most powerful empires in the Islamic world in the 16th century that had strong rivalry due to religious and military conflicts. The Safavids were a Shi’i Muslim empire, opposed by the Sunni Ottoman empire. Their conflicts of territorial claims along with power and influence caused their tension to remain.[8] While their invitation to the circumcision ceremony may be seen as an attempt to improve relations, it was also a way for Ottomans to show their power by inviting the Safavids to attend and participate in the Ottoman celebrations.

Nakkas Osman was a famous 16th-century Ottoman artist known for his intricate art of different scenes from the Ottoman Empire. His work is known for its high level of detail and traditional techniques. In addition to several European accounts, many imperial-commissioned festival books arose, becoming the first examples of the genre in Ottoman literature[9]. This specific painting of wrestlers was found in the Imperial Festival Book (Surname-I Humayun), commissioned in 1582 by Sultan Murad III for Prince Mehmet’s celebrations. The work was completed in 1588 and the sole copy is located in the Topkapi Palace Museum Library. The illustrations were produced by Osman, and contained 250 miniatures[10]. Osman covers a great level of detail with the split of the image differentiating the Sultan from the attendees and wrestlers. The colorful painting allows an understanding of this being a celebratory event, with the neutral colors on the wrestlers potentially showing this activity as casual circumstances. The similar clothing and appearance contrasting with that of those on the side show the difference in their positions at the festivities.

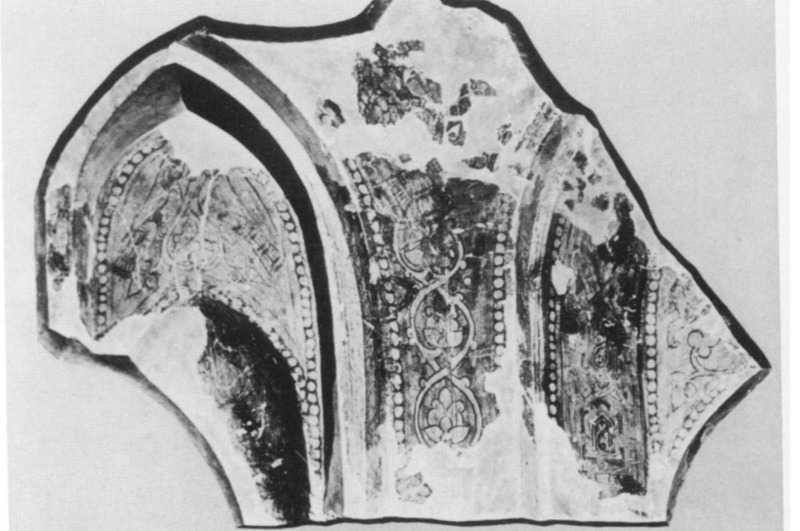

This painting can be compared to 3 drawings of wrestlers in the Cairo Museum of Islamic Art. The first figure is a fragment of the drawing on paper that shows a man engaged in a match. While the use of no gear and no turban might show this as a casual match, the twisted form of each player shows the use of professional techniques[11]. The details attribute to Fatimid paintings, allowing us to observe the popularity of this activity throughout Islamic History within different empires and periods. The other two figures include wrestling matches on a ceramic bowl and wall painting, pulling in different Abbasid and Hellenistic elements that show a different time period of the Fatimids, showing the continuous practice of the rendering of everyday life in Egypt and the power of tradition[12]. The Abbasid court present in these pieces further shows the popularity of wrestling in another Islamic period.

Sports, games, and competitions have always been important in Islamic life. Muslims have participated in activities such as wrestling throughout history as a way of entertainment and socialization. Involving wrestling in circumcision ceremonies highlight the importance of this sport in the Islamic world, as it demonstrates a bond in the community. The bond in the community could be connected further into the act of diplomatic gestures to remind of the Ottoman victories throughout Islamic history. As wrestling became deeply engrained in Ottoman society and heritage, promoting the sport at a celebration of thousands of attendees allows them to promote their culture and further strengthen it with their pride. This connects to the theme of games, sports, and competitions in the Islamic world, as we are able to understand the importance of these in all periods of the Islamic world.

This allows us to understand the connection between the overarching theme of leisure in the Islamic world through sports and competitions in wrestling. Islam encourages productivity and leisure activities that promote physical well-being, as it is necessary for balancing a fulfilling life[13]. Muhammad, the last Prophet of Islam, had commanded the believers to make time for leisure, making it very popular and essential since early Islam[14]. Nakkas Osman’s painting of wrestlers wrestling allows viewers to understand the importance of wrestling and productive leisure activities in the Ottoman Empire as a way of showing its strength and culture. When Medieval Muslim rulers took a rest from their political affairs and ruling, they would turn to exclusive entertainment, including wrestling, showing its importance in the Medieval Islamic world in leisure[15].

[1] Terzioglu, Derin, The Imperial Circumcision Festival of 1582: An Interpretation (Muqarnas, 1995, Vol 12 (1995)), 85

[2] Terzioglu, The Imperial Circumcision Festival, 85.

[3] Suraiya Faroqhi, Subject of the Sultan: Culture and Daily Life in the Ottoman Empire (London: I.B. Tauris, 2005), 88.

[4] Merdad Kia, Daily Life in the Ottoman Empire (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2011), 31.

[5] Kia, Daily Life, 52.

[6] Kia, Daily Life, 54.

[7] Faroqhi, Subject of the Sultan, 118.

[8] D’souza, Rohan. “Crisis before the Fall: Some Speculations on the Decline of the Ottomans, Safavids and Mughals.” Social Scientist 30, no. 9/10 (2002), 4.

[9] Terzioglu, The Imperial Circumcision Festival, 85.

[10] “Illustrations from the Surname-I Humayan, Ottoman, 1588 AD.

[11] Ernst J. Grube, "A Drawing of Wrestlers in the Cairo Museum of Islamic Art," Quaderni di Studi Arabi 3 (1985): 91.

[12] Grube, A Drawing of Wrestlers, 95.

[13] Ibrahim Hilmi, Leisure and Islam (Kuala Lumpur: International Institute of Islamic Thought and Civilization, 1999), 15.

[14] Uriya Shavit, Sport and Society in the Global Age (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2012), [265]

[15] Boaz Shoshan, "High Culture and Popular Culture in Medieval Islam," The Journal of Popular Culture 36, no. 1 (2002): 70-71.

Works Cited

D’souza, Rohan. “Crisis before the Fall: Some Speculations on the Decline of the Ottomans, Safavids and Mughals.” Social Scientist 30, no. 9/10 (2002): 3–30. https://doi.org/10.2307/3517956.

Faroqhi, Suraiya, and Martin Bott. Subjects of the Sultan: Culture and Daily Life in the Ottoman Empire. London: I.B. Tauris Publishers, 2000.

GRUBE, ERNST J. “A DRAWING OF WRESTLERS IN THE CAIRO MUSEUM OF ISLAMIC ART.” Quaderni Di Studi Arabi 3 (1985): 89–106. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25802570.

Ibrahim, Hilmi. “Leisure and Islam.” Leisure Studies 1, no. 2 (1982): 197–210. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614368200390161.

“Illustrations from the Surname-I Humayan, Ottoman, 1588 AD. , Accessed April 28th 2023. “http://warfare.6te.net/Ottoman/Surname-i_Humayun-Topkapi_Hazine_1344-Fireworks lg.html

Kia, Mehrdad. Daily Life in the Ottoman Empire. Santa Barbara, CA: Greenwood, 2011.

Shavit, Uriya, and Ofir Winter. “Sports in Contemporary Islamic Law.” Islamic Law and Society 18, no. 2 (2011): 250–80. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23034925.

Shoshan, Boaz. “High Culture and Popular Culture in Medieval Islam.” Studia Islamica, no. 73 (1991): 67–107. https://doi.org/10.2307/1595956.

Terzioglu, Derin. “The Imperial Circumcision Festival of 1582: An Interpretation.” Muqarnas, 1995, Vol. 12: pp 84-100. http://www.jstor.com/stable/1523225