Reliquary Textile Catalogue Entry

Just as clothing is an important aspect of many peoples’ lives today, whether it be in fashion, comfort, or just general protection, the type and material of clothing people wore was even more important in the beginnings of Islam. Clothing and textiles were so important to Islamic culture that they represented the dominant social values and codes of behavior that were prominent back then. A person’s status in society could be easily measured by the amount of and nature of the textiles they owned.[1] Textiles represented the wealth of the ruling dynasties, set the basis for beauty and fashion, and were a major economic staple for the beginnings of the Islamic world.[2]

Such grandiose textiles were regarded as such due to the high levels of expertise required in both weaving and dyeing techniques and the high costs of raw materials.[3] Weaving was primarily done on drawlooms, a large loom that required two people to operate fully. One worker called the weaver would work the loom itself and control the structure of the textile. The other worker called the drawboy would be responsible for directing the creation of the various patterns found on the textile.[4] These textiles were first made of materials such as wool and linen, but as the want for more luxurious designs rose, weavers started to use silk due to its breathability and softer feel.[5] However, the use of silk caused these textiles to rise in value dramatically due to the high amount of labor and specific climate needed in performing sericulture.[6] Dyes needed to color the textiles also needed to be imported which only caused the value of these pieces to rise even more. These dyes included Indigo from Upper Egypt, kermes from Crete and the Peloponnesos, and saffron from Persia and Asia Minor. Gold and silver from Upper Egypt and India respectively were also used and helped to create more luxurious textiles.[7]

A perfect example of an Islamic silk textile would be the textile found at the reliquary of Saint Anastasius the Fuller. Saint Anastasius himself was an Italian Christian martyr who was sentenced to death after he painted a cross on his door during the Roman persecution of Christians ca. 304 CE. Due to the fear of coastal raiders, the bodies of Saint Anastasius and Saint Dominus, a bishop and fellow martyr, were moved from Salona to the cathedral of Saint Dominus in Split, Croatia. The silk fragment was then brought to cover the reliquary of Saint Anastasius by Archbishop Joannes, a prominent member of the Second Nicene Council. The fragment was only first recorded in 1993 by Susanne Biedermann, a textile expert, who was initially only studying the reliquary of Saint Anastasius. Then in 2008, Anna Muthesius, another textile researcher, was the first to officially publish the silk.[8]

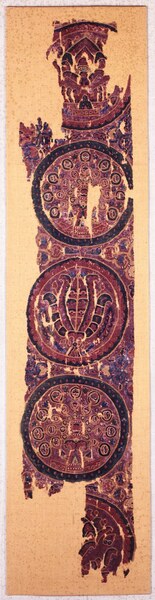

The silk fragment itself is theorized to have been made ca. the first half of the 8th century CE during the later part of the Umayyad dynasty using the drawloom method. A variety of colors were used in weaving this textile, consisting of purple, red, blue, green, and yellow, with purple being the main color used for the background. The areas of uneven coloring suggest that a form of resist dyeing was used, a repeatable technique for dyeing where a substance is used to protect areas of the textile and the unprotected areas are then dyed.[9] The white specs that can be found on the surface are due to the glue used to place the textile on a secondary textile and then on a rectangular board to help preserve the piece.[10]

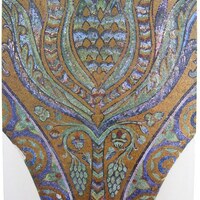

Despite being heavily damaged in some areas, the silk measures ninety-eight centimeters in length by twenty centimeters in width and is made up of five inhabited medallions arranged vertically on the piece. From the top to bottom, the first medallion depicts a plant with a pyramid shaped feature on its upper end, the second medallion depicts an ornament resembling a peacock’s tail, the third medallion depicts a flower like a lotus, the fourth medallion depicts another ornament resembling a peacock’s tail, and the fifth medallion depicts another plant with a pyramid feature. The first and last medallions are the areas that sustained the most damage due to the passage of time. The boarders of the medallions consist of small purple and red dots.[11] These types of dots on textiles help add detail without adding too much to the overall cost of the textile.[12] The area between the medallions consists of vegetal ornaments of vine leaves and half-palmette leaves.[13] These ornaments alternate between blue, yellow, and purple which helps add to the dynamic flow of the overall textile.[14]

Upon closer inspection, the vegetal motifs found within each medallion can be interpreted as luxurious pieces of jewelry. The jewelry found resembles those which would be found in crowns and rings of the wealthy of the time. Furthermore, this idea of jewelry residing in each medallion instead of a vegetal motif is further supported by the discovery that each medallion also consists of a large base and high pedestal that supports each piece of jewelry. The use of a base and pedestal results in a slight three-dimensional effect that plays on the viewer’s vision. Additionally, the pattern of alternating bases and pedestals suggests that the textile was meant to be hung or worn vertically, with the medallion that is damaged on both its left and right sides meant to be on top.[15]

Extra details found within the medallions cause the original vegetal ornaments to become more compact and firmer in design, almost resembling a sculpture. When compared with other works created around the same time frame with similar motifs, such as a tree wall mosaic from the Dome of the Rock, the vegetal designs found within the Saint Anastasius silk fragment seem to look stiffer rather than natural.[16] For example, in the second and fourth medallions that contain the peacock tails, what upon first inspection was considered feathers can also be distinguished as rings and chains connecting to each other. Additionally, carved stucco medallions found in early Umayyad palaces contain very similar looking stiff vegetal ornaments that are strikingly like the ornaments found on the silk fragment. In a similar fashion as well, the palace medallions are also arranged in rows that form a decorative band. This comparison between the palace and silk medallions leads us to believe that the silk textile is indeed early Umayyad in creation and may have either been hung on the walls in the palace or worn by the palace ruler themself. By having the juxtaposition of both hard and soft materials with similar designs, the visual experience would have been enriched and heightened for any visitor or onlooker.[17]

The use of red for the textile fragment was intentional as it relates to prophetic qualities, the caliphate, and imperial connotations. The importance of red has roots in the Bible all the way in the beginnings of the book of Exodus where the making of the first tabernacle was being recorded, where any red textile was brought to assist with the project. There are also multiple instances where God inspires and assists certain people with weaving with specific colored yarn, one of those colors being red. The Bible also has a few scenarios where red is shown as a royal color instead of the normal purple color. For example, it is also said that King Solomon had a red banner that would shine brightly even in the night sky. Almost every Islamic caliph wanted to be just like Solomon, so possessing red textiles just as Solomon did is an easy step towards that goal. Additionally, in Islamic tradition, the Prophet Muhammad has been recorded as wearing a red suit multiple times and resided in a red tent. Lastly, the Umayyads themselves were obsessed with gemstones and minerology, to the point where there were books published on the different types and prices of rubies. With holding gemstones in such high regard, especially rubies, red held a special place for the Umayyads. There also exists a statue depicting an Umayyad caliph that has faded red pigment on the clothing and facial hair.[18]

Despite all the evidence presented, the original intended use of the silk textile is still not certain. What is known is that it was either used as a piece of clothing for an Umayyad caliph or used as decoration for an Umayyad caliph’s palace. Due to the stitching, breathability, and temperature regulating properties of the silk, the possibility of the fragment initially being used as clothing is favored. If the fragment’s original purpose was to clothe a caliph, then it would have served as a perfect piece of leisurewear due to still showing off the splendor and power of the caliph without the caliph having to wear their full outfit. Though not knowing the original purpose, the use of the silk did transform as time went on. Although not in the traditional sense, the silk fragment did help clothe the reliquary of Saint Anastasius the Fuller, thus in a way the fragment did serve to clothe at some point during its existence.[19]

[1] Lisa Golombek, “The Draped Universe of Islam,” in Content and Context of Visual Arts in the Islamic World, ed. Priscilla P. Soucek (University Park, PA: Published for the College Art Association of America by the Pennsylvania State University Press, 1988), 50.

[2] Louise W. Mackie, "Islamic Textiles," in Byzantine Silk on the Silk Roads: Journeys between East and West, Past and Present, ed. Sarah E. Braddock Clarke and Ryoko Yamanaka Kondo (London: Bloomsbury Visual Arts, 2022), 83, http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781350099302.ch-7.

[3] David Jacoby, “Silk Economics and Cross-Cultural Artistic Interaction: Byzantium, the Muslim World, and the Christian West,” Dumbarton Oaks Papers 58 (2004): 205, https://doi.org/10.2307/3591386.

[4] Mackie, “Islamic Textiles,” 84.

[5] Adele Coulin Weibel, “Egypto-Islamic Textiles,” Bulletin of the Detroit Institute of Arts of the City of Detroit 12, no. 8 (1931): 93.

[6] Mackie, “Islamic Textiles,” 84.

[7] Coulin, “Egypto-Islamic Textiles,” 93.

[8] Avinoam Shalem, “‘The Nation Has Put On Garments of Blood’: An Early Islamic Red Silken Tapestry in Split,” in Catalogue of the Textiles in the Dumbarton Oaks Byzantine Collection, ed. Gudrun Bühl and Elizabeth Dospěl Williams (Washington, D.C. : Dumbarton Oaks Research Library & Collection, 2019), accessed April 29, 2023, https://www.doaks.org/resources/textiles/essays/shalem.

[9] Friedrich Spuhler, Early Islamic Textiles from Along the Silk Road (London: Thames & Hudson, 2020), 275.

[10] Shalem, “Tapestry in Split.”

[11] Shalem, “Tapestry in Split.”

[12] Spuhler, Early Islamic Textiles, 186.

[13] Spuhler, Early Islamic Textiles, 99.

[14] Shalem, “Tapestry in Split.”

[15] Shalem, “Tapestry in Split.”

[16] Patricia L. Baker, Islamic Textiles (London: British Museum Press, 1995), 39.

[17] Shalem, “Tapestry in Split.”

[18] Shalem, “Tapestry in Split.”

[19] Shalem, “Tapestry in Split.”