Safavid Velvet Catalogue Entry

The Safavid dynasty, which dates 1501- 1722, is the greatest dynasty to materialize from Iran in the Islamic world and the textile industry was essential to their economy.[1] In 1501, Shah Isma’il captured Tabriz and founded the Safavid dynasty, while establishing Shi’ism as the official religion. This united Iranian territory under an identity which provided the foundation that lasts in modern Iran.[2] The map to the right shows the Safavid territory that Shah Isma’il put together in the 16th century. Shah Tahmasp, who reigned from 1524- 1576, became shah after the death of Shah Isma’il. Shah Tahmasp was shah, a title for the monarch of Iran, during the mid 16th century when the Safavid velvet of this catalogue entry is dated to.[3] The terrible survival rate of Persian carpets and textiles from the 16th century, on top of the absence of court records from early Safavid Period, hinders the study of these textiles.[4] This makes it difficult to identify the location some of these textiles originate from as textiles move around once they are made. Scientific techniques are now being used to analyze the natural dyes and metal threads in Safavid versus Mughal velvets to try to differentiate the velvets of these two cultures without court records.[5]

No matter the missing records, many things are known about the uses of lucury Safavid textiles. Luxury textiles were custom in Safavid diplomacy. For example, “Shah Tahmasp presented three hundred gold-brocaded silks, a thousand expensive silks, and another thousand foreign velvets, as well as a lavish tent furnished with costly carpets and gold-threaded embroidery, to Sīnan Pāsha, the esteemed Ottoman court architect from Istanbul”.[6] Luxury textiles were also used to adorn walkways, capital cities, and bazaars as a symbol of the dynasties power and wealth. The textile industry was essential to the Safavid dynasty. In 1509-10, Shah Isma’il had founded thirty-three royal workshops for textile production. By late 16th century, there was a shift from spices to raw silk as the most desired commodity in the European markets. This was good timing for the Safavid dynasty as before this, Armenian merchants controlled the silk industry and prevented the shahs from profiting off silk sales.[7] The Luxury textiles woven in royal workshops were available in the bazaars, or marketplaces.

The textiles of Safavid Iran show the greatest expertise and artistic skill out of all the textiles produced during the Islamic era. Safavid velvets are the most colorful velvets ever woven and have a “satin-weave foundation, cut silk pile, frequent metal-wrapped wefts, and occasional metal-wrapped loops. Iranian weavers invented the technique of cutting pile-warps on the back and replacing them with different colored pile-warps according to the design, a practice called pile-warp substitution”.[8] The technical prowess of the Safavid weavers made possible extremely intricate floral and figural designs.[9]

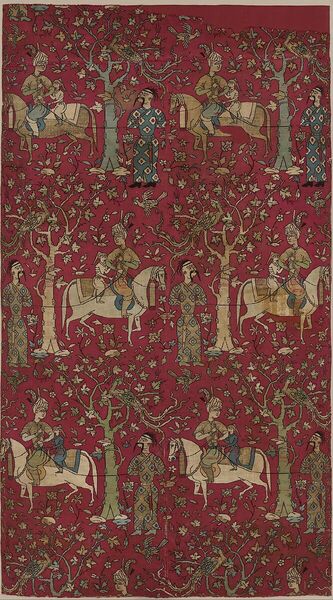

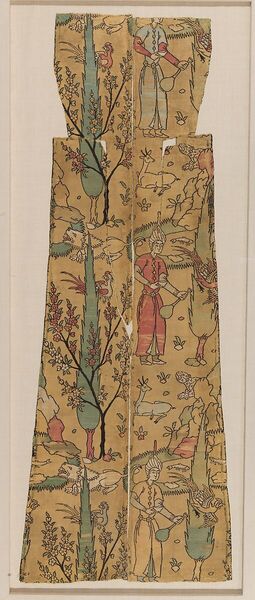

Safavid textiles in the 16th century often featured figural imagery taken from manuscript paintings of the time and often place the human figures in landscapes. The patterns present popular stories in Iranian literature relating to leisurely activities such as royal hunting or relaxing in a garden.[10] Occasionally, scenes of imperial power would be depicted instead of scenes of leisure as with the textile to the left of the Safavid courtiers leading Georgian captives. In this textile, the victory of Shah Tahmasp over the Georgians is celebrated with the Safavid riders in mid 16th century clothing drags along Georgian prisoners with their hands tied behind their backs.[11] While this textile depicts a scene very different from the Safavid velvet of focus in this catalogue entry, it showcases a different source of inspiration for textiles whilst showing the same attire worn at that time.

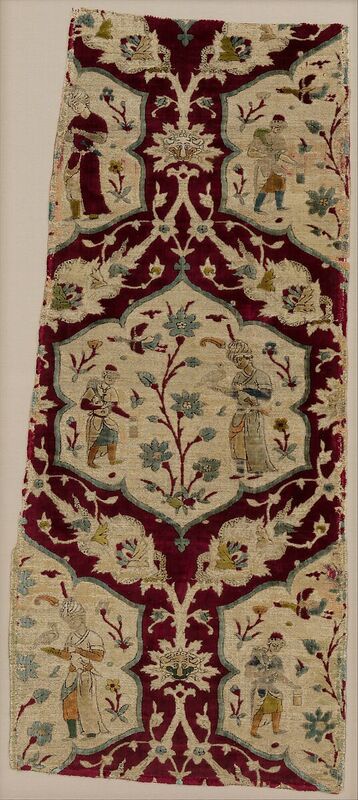

The many colors in the pile of the Safavid velvet of focus shown to the right are achieved by the weaving technique explained above know as pile-warp substitution. The faded silver in the background of the medallions and in the ornament that weaves in between the medallions achieved by specially prepared metallic threads “consisting of a core of white silk wrapped spiral fashion with silver which has been beaten into an extremely thin foil and then cut into minute strips. The silver usually has a high gold content”.[12] Along with the metallic threads, most of the other colors have faded to some degree due to sensitivity to light. However, the deep burgundy color which sits mainly in the background is luckily resistant to fading and is achieved by dying the silk pile for the textile with an insect- derived dye, most likely lac imported from India.[13] The textile features an ogival lattice pattern with hexagonal medallions that have pointed lobes. In the winding spaces between the medallions, spotted dragons wrap around the vegetal ornament. The junction points for the vegital ornament between the medallions features a monster mask that is a motif of antiquity in Asia and is thought to have a protective function.[14] Inside the medallions is a prince and his attendant participating in falconry. The monster mask possibly sits in between the medallions to serve as protection for the prince while he is out participating in falconry.

The feathered turban of the prince in the medallions is a specific type of Safavid turban in the 16th century called the taj Haidari. The taj Haidari is a white turban “with twelve folds wrapped over a red felt cap with a baton”.[15] All royalty and administrative personal wore this turban as an expression of political loyalty. While the color of the prince’s dress in each medallion changes, the one thing that is consistent is the coloring of the feathered turban. The prince’s clothing matches the dress at that time consisting of loose, ankle-length trousers that lie under a long robe which is tucked on one side into a leather belt with floral- shaped metal fastenings. By tucking the robe into the belt, the under color of the robe is revealed. The prince's dagger sits in the belt. The clothing layers are stacked like this to emphasize the contrasting colors that include the blue, red, and orange colors as seen on the prince in this velvet.[16] The tucking of the robe into the belt was often seen in miniature paintings of the time and while the origin could have been for practical purposes, “it appears more as a fashionable mode of dress for showing off the colored linings and lowered garments”.[17] All of these clothing details on the prince add to the dating of this velvet as mid 16th century Safavid as, for example, the taj Haidari turban was no longer in use after Shah Tahmasp reign end in 1576.[18]

The prince in the medallion is accompanied by an attendant while engaging in the princely pastime of falconry. Falconry was a result of the early advanced civilizations in the Middle East. “Falcons cannot be bred in captivity, and thus each individual bird presents a new and ever varying experiment in trapping and training.… Wealth of leisure, great patience, sensitivity and ingenuity… make a successful falconer”.[19] The sport of falconry was not something everyone could do. It was a leisurely activity connected to royalty and the wealthy. In the moment shown on the velvet, the prince’s attendant holds a bag and a receptacle. A duck flies away from the prince, or falconer, as the falcon sits on the prince's gloved hand waiting for his master to give the command to go and kill the duck. There is a power dynamic positioning in this scene as the attendant appears much smaller in size than the prince. At least five other fragments of this same textile have survived.[20]

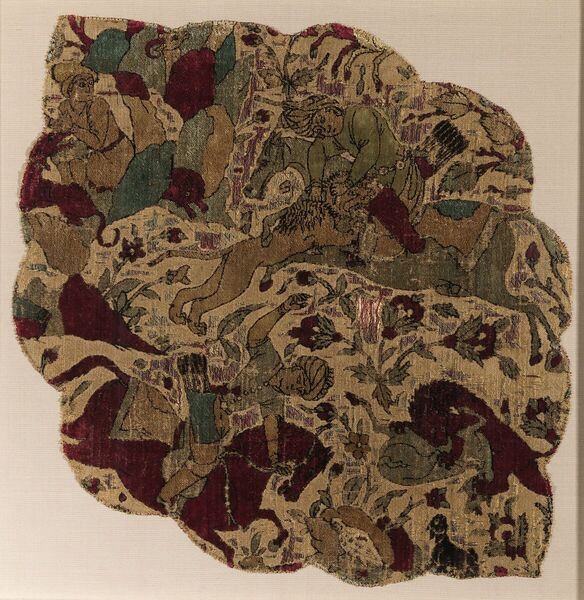

Leisurely scenes related to hunting were common in Safavid velvets. In the Safavid velvet to the right, there is a different kind of hunting scene depicted. This velvet is also dated to the mid 16th century and features hunters on horseback going after their prey. This velvet is an example of a different use of Safavid textiles. The history of this textile is that it was used in the interior of an imperial tent which is known because the main fragment of this piece has a circular hole in the center for a tent’s center supporting pole.[21] This velvet textile also features the deep burgundy color mentioned before in relation to the Safavid velvet of focus in this catalogue entry, as well as similar vegetation and figural design.

The Safavid textile to the left is a silk lampas and was once part of a robe. This silk textile gives insight into how colors look slightly different on a silk versus a velvet textile in the 16th century. This textile depicts a repeating pattern of wine bearers in a landscape with cypress and blossoming prunus trees and a pond with fish in it and shows a different type of leisurely activity typically depicted in Safavid textiles.[22] The design of this textile is very similar to manuscripts produced during the reign of Shah Tahmasp and the wine bearer wears a taj Haidari turban, hence why it is dated to the mid 16th century.

While the exact use of this Safavid velvet is unknown unlike the two textiles just discussed, art historians believe the inspiration at least came from the manuscript paintings of the time as with many other textiles of the time. It depicts a scene of the princely pastime of falconry while the prince wears the taj Haidari to signify his status. The hexagonal medallions which contain the prince’s hunting scene are surrounded by the deep burgundy color and vegetal designs with animals woven in. No matter it’s use, this Safavid velvet, shown again to the right, is a beautiful culmination of mid 16th century Safavid Velvet designs and themes.

[1] Susan Yalman, “The Art of the Safavids before 1600,” Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Published October 2002, Accessed on April 22, 2023, http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/safa/hd_safa.htm.

[2] Louise W. Mackie, Symbols of Power: Luxury Textiles from Islamic Lands, 7th-21st Century (Cleveland, OH: Cleveland Museum of Art, 2015), 340.

[3] Mackie, Symbols of Power, 340.

[4] Jon Thompson and Sheila R. Canby, Hunt for Paradise: Court Arts of Safavid Iran, 1501- 1576 (New York: Asia Society, 2003), 280/304.

[5] Nobuko Shibayama, et al, “Analysis of Natural Dyes and Metal Threads Used in 16th -18th Century Persian/Safavid and Indian/Mughal Velvets by HPLC-PDA and SEM-EDS to Investigate the System to Differentiate Velvets of These Two Cultures,” Heritage Science 3, no. 12 (2015), https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-015-0037-2.

[6] Mackie, Symbols of Power, 340.

[7] Mackie, Symbols of Power, 342-343.

[8] Mackie, Symbols of Power, 345-346.

[9] Daniel Walker, “Islamic,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 53, no. 3 (1995): 31, https://doi.org/10.2307/3258788.

[10] Mackie, Symbols of Power, 346.

[11] Mackie, Symbols of Power, 347-349.

[12] Thompson and Canby, Hunt for Paradise, 288.

[13] Thompson and Canby, Hunt for Paradise, 288.

[14] Thompson and Canby, Hunt for Paradise, 288.

[15] Nazanin Hedayat Munroe, “Fashion in Safavid Iran,” Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Published October 2013, Accessed April 22, 2023, http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/safa_f/hd_safa_f.htm.

[16] Munroe, “Fashion in Safavid Iran.”

[17] Thompson and Canby, Hunt for Paradise, 288.

[18] Munroe, “Fashion in Safavid Iran.”

[19] Hans J Epstein, “The Origin and Earliest History of Falconry,” Isis 34, no. 6 (1943): 497.

[20] Walker, “Islamic,” 31.

[21] G.T, “A Persian Velvet,” Bulletin of the Museum of Fine Arts 26, no. 154 (1928): 24-25.

[22] Thompson and Canby, Hunt for Paradise, 283.