Galland Manuscript Catalogue Entry

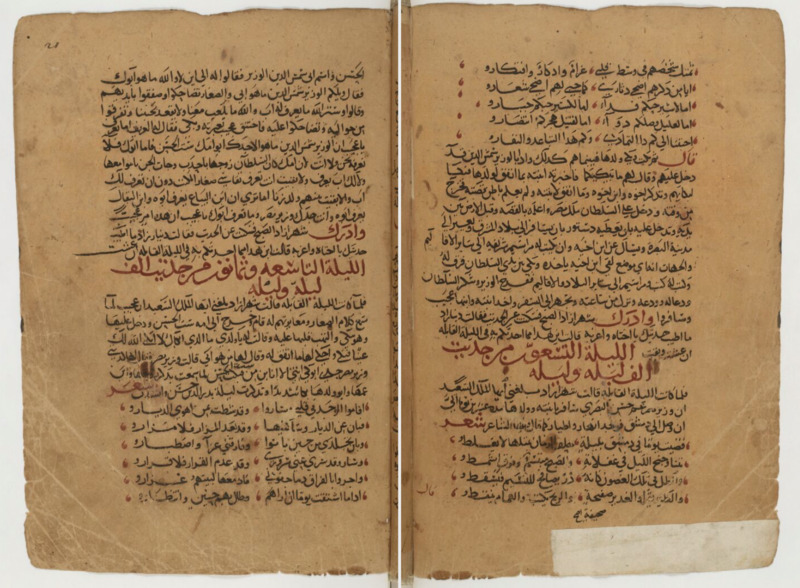

In December of 1701, Antione Galland acquired a three-volume manuscript of stories originating in Syria.[i] His possession and subsequent translation of this work into French marked the introduction of The Thousand and One Nights stories into the minds of western Europe. At the time, he did not know that he had in his posession the oldest and most complete written account of the stories that had existed orally for centuries. This manuscript, and Galland’s translation, editing, and additions shaped the view that western Europe had on Islamic culture and fed into orientalism through his stylistic choices.

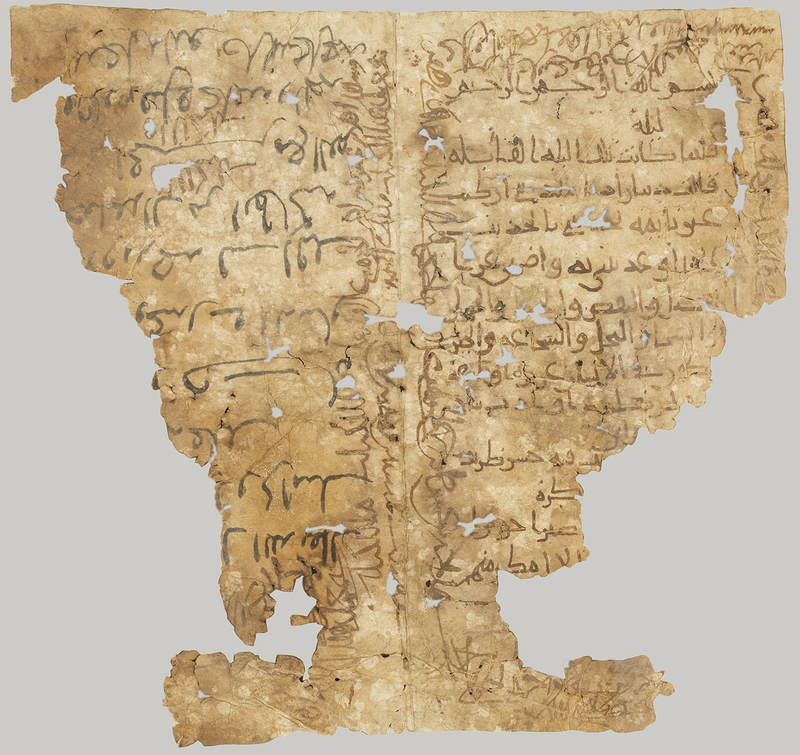

The Galland manuscript is the oldest and most complete written record of The Thousand and One Nights stories; it is only predated by one page of a 9th Century fragment. The age of this manuscript has been a major source of debate since its acquisition. The main point of discussion concerns the mention in night 133 of the coin ashrafī. This term, interpreted by Mushin Mahdi, is in reference to a coin put in circulation between 1290 and 1293, putting a post quem date in the early 14th Century.[ii] In a rebuttal, Heinz Grotzfeld explains why the coin in reference must have occurred after a coinage reform between 1412 and 1437 CE that standardized them by weight. Because the reference to ashrafī in the text are in terms of count rather than weight, as well as the late 15th century development of ashrafī being interchangeable with other terms for coins like dīnār, that a post quem date for the manuscript cannot be earlier than 1450.[iii] Because of the nature of the dating technique, however, being only from one reference to one coin in the entire manuscript, no definitive date can be confirmed to any degree more specific than 14th to 15th Century.

At least a hundred years after its creation, this manuscript ended up in the hands of Antione Galland. An “antiquarian, classicist, and Orientalist,”[iv] Galland spent many years traveling throughout the Mediterranean and the Middle East with no knowledge of the stories of the Nights. After hearing the tale of the “Seven Voyages of Sinbad” and its attribution to the Nights, Galland turned his focus towards obtaining a written version of the collection. Despite the story of “Sinbad” never being found attributed to the Nights in any written versions, it sparked the interest in the work that led to his acquisition of the manuscript in 1701.[v] Between 1704 and 1717, twelve volumes of the translated Nights were published. The initial eight volumes contained the extent of content found in the original;[vi] the remaining four volumes contained additional stories. The manuscript contained only 282 Nights, which Galland was conviced there to be a complete work somewhere containing all 1,001.[vii] Though no author is known for the manuscript, and the stories have existed for centuries in an oral tradition, Antione Galland, in his search for a complete set of The Thousand and One Nights traveled again to Syria in 1709 and enlisted the help of the storyteller Hanna Dyâb. From him, he acquired orally sixteen stories to supplement the final four volumes. Despite efforts to maintain a stylistic continuity between the stories present in the original and those from Hanna, the later volumes were a work of creation from Galland, taking summaries from what he was told and adapting them into the universe that the Nights existed in.[viii] This began a tradition of later translators following similar practices, fabricating stories to insert into the Nights in order to create more complete translations.[ix] Controversy surrounds his decision to supplement the stories, as well as his neglect to be specific in his publications which stories were translated and which were created.

Additionally, through Galland’s translation and addition, he influenced the western idea of Islamic culture and contributed to the orientalist tradition, making the Middle East out to be an exotic and mystical place. The decision that he made in the translation process to not supplement the manuscript with any other similar texts meant that any complexities or difficulties found in the original had to be interpreted from his own, distinctly French, point of view.[x] His interpretations often led to an incorrect and harmful view of Islamic culture. One such example is of the ghoul, a traditional Arabic folklore creature, that appears with a combination of beastlike and human features and lives in the wilderness intent on frightening people.[xi] In Galland’s version of one such story depicting a ghoul, he exaggerated the fearful characteristics of the creature, introducing the idea that ghouls feed on human flesh and will go to graveyards to consume the corpses.[xii] This story, being one that did not come from the manuscript text, has no written record of these characteristics. Galland created the narrative from a story he was told orally, and in turn transformed a traditional creature from folklore into a fearful representation of Arabic culture, as well as popularizing the term and idea of the ghoul with the west. Galland’s misrepresentation of the manuscript also led to a precedent that inspired other authors and translators to make their own compilations of Islamic stories, becoming just as popular in western Europe.[xiii] The European bias against these stories, despite their popularity, was seen in the lack of scholarly effort given to find their origins and means of transference. Similar to the traditional western attitudes given to many pieces of Islamic culture, these stories were seen as exclusively entertainment, and held little to no scholarly value.[xiv]

Despite the influence that this manuscript and its translation had on western Europe, the original context that these stories were made in and shared is very important. Western European scholars may have traditionally deemed the stories pure entertainment and not worthy of scholarly consideration, but the cultural value that they hold cannot be understated. The oral tradition of storytelling is centuries old, and served as entertainment, a leisure activity, and a way to connect as a community. The stories were made in and exist in an Islamic context, and no western reinterpretation can negate that. The content of the stories describe a collective memory that can only have developed in a complex society and culture.[xv]The oral tradition in Islam has existed since its beginnings, with the Quran having been initially communicated from the Prophet for centuries orally, more than written.[xvi] The oral tradition and storytelling form an integral part of Islamic culture, society, entertainment, and leisure.

The Galland Manuscript has had a very important role in modern western society and the way that it views Islamic culture. It contributed to orientalism through Antione Galland’s interpretations in his translation, though it did bring to western Europe a wonderful piece of culture that represented a culmination of centuries of Islamic storytelling tradition. Though the problems from the translation can still be seen and are still debated, The Thousand and One Nights is undoubtably the most influential piece of entertainment culture to come from Islamic sources.

[i] Mushin Mahdi, The Thousand and One Nights (Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1995), 20.

[ii] Mahdi, Nights, frontispiece.

[iii] Heinz Grotzfeld, “The Age of the Galland Manuscript of the Nights: Numismatic Evidence for Dating a Manuscript,” Journal of Arabic and Islamic Studies, 1 (1996/97): 63.

[iv] Mahdi, Nights, 14.

[v] Mahdi, Nights, 18-19.

[vi] Sylvette Larzul, “Further Considerations on Galland’s Mille et Une Nuits: A Study of the Tales Told by Hanna,” Marvels & Tales 18, no. 2 (2004): 259.

[vii] Mahdi, Nights, 23.

[viii] Larzul, “Further Considerations,” 270.

[ix] Mahdi, Nights, 23.

[x] Mahdi, Nights, 44.

[xi] Ahmed K. Al-Rawi, “The Arabic Ghoul and its Western Transformations,” Folklore 120, no. 3 (2009): 296.

[xii] Al-Rawi, “The Arabic Ghoul,” 299.

[xiii] Richard van Leeuwen and Arnoud Vrolijk, The “Thousand and One Nights” and Orientalism in the Dutch Republic, 1700-1800: Galland, Cuper, De Flines (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2019), 16, Jstor.

[xiv] Van Leeuwen and Vrolijk, Orientalism, 17.

[xv] Mushin J. al-Musawi, The Islamic Context of The Thousand and One Nights (New York: Columbia University Press, 2009), 9

[xvi] Thomas Herzog, “Orality and the Tradition of Arabic Epic Storytelling,” In Medieval Oral Literature, ed. Karl Reichl (Berlin: de Gruyer, 2012), 627

Bibliography

Grotzfeld, Heinz. “The Age of the Galland Manuscript of the Nights: Numismatic Evidence for Dating a Manuscript.” Journal of Arabic and Islamic Studies 1 (1996/97): 50-64. https://doi.org/10.5617/jais.4545.

Herzog, Thomas. “Orality and the Tradition of Arabic Epic Storytelling.” In Medieval Oral Literature, Edited by Karl Reichl, 629-652. Berlin/Boston: de Gruyer, 2012.

Larzul, Sylvette. “Further Considerations on Galland’s Mille et Une Nuits: A Study of the Tales Told by Hanna.” Marvels & Tales 18, no. 2 (2004): 258-71.

Mahdi, Muhsin. The Thousand and One Nights. Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1995.

Al-Musawi, Mushin J. The Islamic Context of The Thousand and One Nights. New York: Columbia University Press, 2009. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7312/al-m14634.

Al-Rawi, Ahmed K. “The Arabic Ghoul and Its Western Transformation.” Folklore 120, no. 3 (2009): 291-306. DOI: 10.1080/00155870903219730.

Van Leeuwen, Richard and Arnoud Vrolijk. The “Thousand and One Nights” and Orientalism in the Dutch Republic, 1700-1800: Galland, Cuper, De Flines. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2019. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvfxvc9k.