Catalogue Entry~ Double-Headed Eagle Silk Fragment

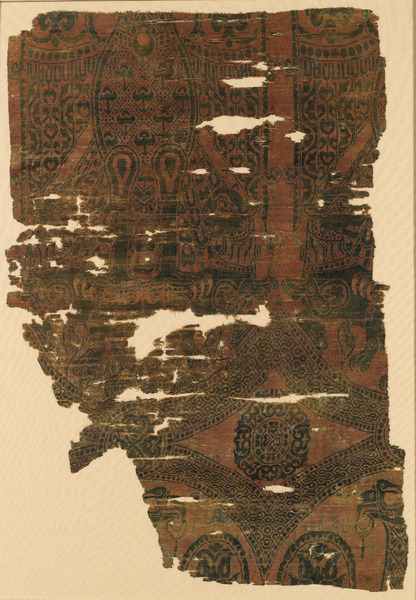

At first glance, this Double-Headed Eagle silk fragment appears tarnished and rather mundane; a piece one may skip over in an exhibit. Though the striking red and dark green hues of the Double-Headed Eagle silk have faded over time, its vibrant history still provides valuable insight into Islamic silk production, high-level gift-giving, and the sense of community created as a result. The eagle silk fragment, see left, is merely a twenty-four-inch by eighteen-inch piece of a much larger textile estimated to be ten times this size when first woven.[i] The pattern repeated on this silk depicts double-headed eagles surrounded by circular scalloped borders with their wings raised.[ii] The double-headed eagles woven in this silk are a common imperial symbol; however, the eagles on this silk vary from the traditional design with their elaborate ornamentation.[iii] A unique twist is provided by the lions, universally feared beasts, trapped in the talons of these powerful birds. The uniqueness and attention to detail featured in this silk not only distinguish it from other Islamic textiles but have made it a symbol of high status in Al-Andalus.[iv]

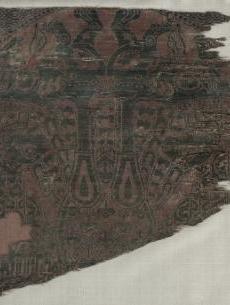

The double-headed eagle silk was almost certainly produced during the late eleventh or early twelfth century.[v]This silk’s extremely long life has caused deterioration which has led to some uncertainty surrounding its creator and the location of its creation. Luckily, due to significant Byzantine influence in the creation of art and architecture in Islamic Spain during the eleventh and twelfth centuries, the time period of its creation was simpler for specialists to agree upon.[vi] The genesis of the double-headed eagle motif is commonly associated with Byzantine culture.[vii] Adapting the design of the silk fragment to include lions shows the imitation of Byzantine characteristics intertwined with Islamic features.[viii] Another silk created during this period, which also features eagle iconography, (see right) helps confirm the double-headed eagle silk’s creation timeline.[ix] Similar to the double-headed eagle silk, this silk displays roundel sequences surrounding eagles, a design characteristic of Spanish silks during the twelfth century.[x] Both of these silks were created during a period in which the Islamic cities of Spain lead the luxury silk production industry in Europe.[xi]

The subjectivity of art history is perfectly represented through the conflicting opinions experts hold about where the eagle silk was produced. The close emulation of Byzantine ideals leads many historians to easily assume that the eagle silk hailed from Byzantium, which at the time had a booming silk industry, yet no one could confirm this with certainty.[xii] In instances such as this, experts are forced to look comparatively. The vast differences, such as color and production style, between the eagle silk and other well-known Byzantine silks make the claim of Byzantine origins less reliable.[xiii]Dorothy Shepherd provides an outlook strongly in favor of Hispano-Islamic creation: strikingly similar silks, also known to replicate Byzantine designs, are known to have been produced in Muslim silk weaving centers in Spain.[xiv] Another argument in support of Hispano-Islamic origin is the double-headed eagles clutching their talons around lions, a depiction of dominance also featured in stone carvings found in Cordoba.[xv] This adaptation strengthens the imperial motif of the double-headed eagle showing that the unknown creator of this silk destined it for powerful ownership.

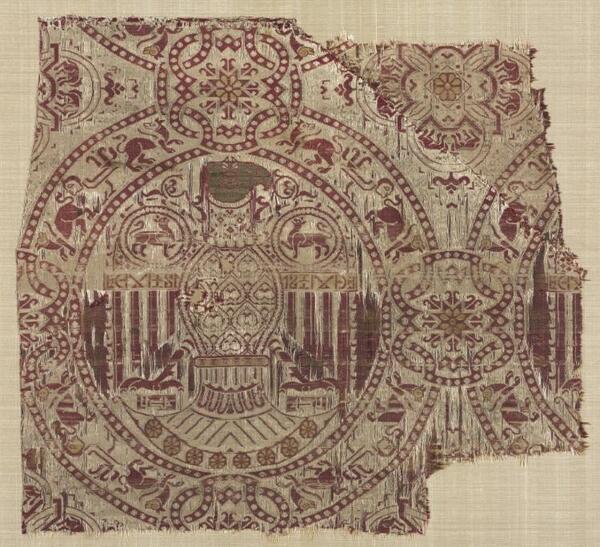

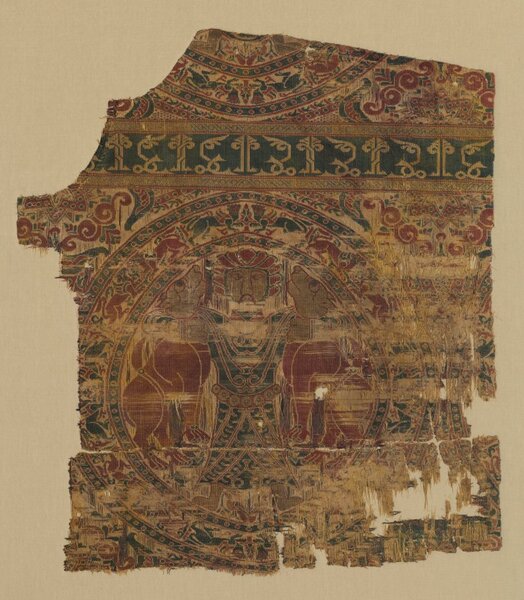

Though its origin remains up for debate, the double-headed eagle silk found its way to the tomb of St. Bernat Calbo, or Bernard Calvo, the bishop of Vic, Spain from 1233-1243.[xvi] This means the eagle silk was already over one hundred years old at the time of Calvo’s burial. It is no fluke that this grand textile was buried with Calvo, the silk is theorized to be a gift to him from a member of Spanish royalty, James I of Aragon.[xvii] The tomb was opened for the first time during the winter of 1888, and the eagle silk was discovered in addition to several other textiles.[xviii] The first of these textiles (see right) depicts a man, with gold threads adorning his features, strangling a lion in each of his arms. This silk was woven through a plain-weave technique, with “prosperity” repeatedly inscribed.[xix] A second textile (see right) was also created during the eleventh century using plain-weave techniques with shimmering gold threads.[xx] The ornamentation of this silk displays sphinxes being confronted by lions.[xxi] The double-headed eagle silk differs significantly, in style and technique, from the others, yet through the common motif of overpowering lions, they all represent the power and respect associated with St. Bernard Calvo. Bernard Calvo was canonized as a saint in the eighteenth century which means that these already magnificent silks are deemed sacred relics because of their contact with his body.[xxii]

After being removed from the tomb, the final stop on the textile’s journey was to various museums and exhibits around the world. After the massive eagle silk was determined to be sacred, it was cut down to at least ten sections and distributed to royalty, clergy, and laypeople.[xxiii] It is considered extremely fortunate to be in possession of one of these silk pieces. Sections were purchased by The Metropolitan Museum of Art and The Cleveland Museum of Art for exhibits featuring Spanish and Islamic art; however, neither museum currently displays their fragments.[xxiv] To put into perspective how massive this silk was in its early days, the approximately two-square-foot section owned by the Metropolitan Museum of Art is considered small, for it only features one complete section of the repeating pattern.[xxv]

As previously mentioned, the creator of this piece remains unknown; however, the fine craftsmanship shows the creator’s high skill level.[xxvi] The artist employed a samite weave using remarkable red, yellow, and dark green shades.[xxvii] The significant symbolism of the double-headed eagle silk makes up for the ambiguity surrounding its creation. During medieval times, silks and other high-quality textiles showed the owner’s prosperity and were frequently exchanged as gifts among royalty.[xxviii] James I of Aragon likely gifted Bernat Calvo this silk to express his gratitude for Calvo’s assistance in overtaking Valencia: a Muslim-controlled port city.[xxix] It is theorized that, after receiving this textile in 1238, Calvo wore this large silk as his holy vestment or chasuble.[xxx] The quality of this silk coupled with its association with foreign lands and royalty would have made it extremely expensive; attainable only for a high-status individual.[xxxi] A gift of this magnitude often portrays an ideological message which exceeds its material value.[xxxii]Calvo’s possession of such a luxurious silk with powerful iconography show his respected and prestigious status.

The circulation of silks created relationships between rulers of distant lands: James of Aragon and St. Bernat Calvo are a prime example. The exchange of textiles with varying style and iconography allowed for expansion of artistic ideals. Specifically, when exchanged as gifts, these textiles represented allegiance and a transference of power.[xxxiii] A textile gift received from a foreign land was regarded with higher prestige than textiles produced domestically.[xxxiv]Textiles held a dominant role in the cultural and artistic exchange between Byzantine and Islamic lands.[xxxv] The fluidity of textile motifs between these Byzantine and Islamic cultures could explain the difficulty in determining the double-headed eagle silk’s origins. The Double-Headed Eagle silk is a perfect example of a luxurious textiles aiding in the formation of imperial relationships.

[i] The Metropolitan Museum of Art. “Textile Fragment with Double-Headed Eagles.” Accessed December 7, 2022, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/468062?ft=islamic+silk&offset=0&rpp=40&pos=6

[ii] Louise Mackie, Symbols of Power: Luxury Textiles from Islamic Lands, 7th-21st Century. Cleveland, OH: Cleveland Museum of Art, 2015.

[iii] The Metropolitan Museum of Art, “Textile Fragment.”

[iv] Mackie, Symbols of Power, 180.

[v] The Metropolitan Museum of Art, “Textile Fragment.”

[vi] The Cleveland Museum of Art. “Samite fragments with double-headed eagles, from the tomb of Saint Bernard Calvo.” September 16, 2022. https://www.clevelandart.org/art/1951.92.

[vii] The Cleveland Museum of Art, “Samite fragments.”

[viii] Dorothy Shepherd, “The Third Silk from the Tomb of Saint Bernard Calvo.” The Bulletin of the Cleveland Museum of Art 39, no. 1 (1952): 11–14. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25141758.

[ix] The Cleveland Museum of Art, “Fragments with eagles.”

[x] The Cleveland Museum of Art, “Fragments with eagles.”

[xi] The Cleveland Museum of Art, “Fragments with eagles.”

[xii] The Cleveland Museum of Art, “Samite fragments.”

[xiii] Shepherd, “Third Silk”, 14.

[xiv] Shepherd, “Third Silk”, 14.

[xv] The Metropolitan Museum of Art, “Textile Fragment.”

[xvi] Dorothy Shepherd, “A Twelfth-Century Hispano-Islamic Silk.” The Bulletin of the Cleveland Museum of Art 38, no. 3 (1951): 59–62. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25141697.

[xvii] The Metropolitan Museum of Art, “Textile Fragment.”

[xviii] Shepherd, “Hispano-Islamic Silk”, 59.

[xix] Mackie, Symbols of Power, 177.

[xx] Mackie, Symbols of Power, 177.

[xxi] Mackie, Symbols of Power, 177.

[xxii] The Metropolitan Museum of Art, “Textile Fragment.”

[xxiii] The Metropolitan Museum of Art, “Textile Fragment.”

[xxiv] The Cleveland Museum of Art, “Samite fragments.”; The Metropolitan Museum of Art, “Textile Fragment.”

[xxv] The Metropolitan Museum of Art, “Textile Fragment.”

[xxvi] The Metropolitan Museum of Art, “Textile Fragment.”

[xxvii] Mackie, Symbols of Power, 180.

[xxviii] Al-Zubayr, Gifts and Rarities, 35.

[xxix] Mackie, Symbols of Power, 180.; The Metropolitan Museum of Art, “Textile Fragment.”

[xxx] The Metropolitan Museum of Art, “Textile Fragment.”

[xxxi] The Metropolitan Museum of Art, “Textile Fragment.”

[xxxii] Anthony Cutler, “Gifts and Gift Exchange as Aspects of the Byzantine, Arab, and Related Economies.” Dumbarton Oaks Papers 55 (2001): 247–78. https://doi.org/10.2307/1291821.

[xxxiii] Eva Hoffman. “Pathways of Portability: Islamic and Christian Interchange from the Tenth to the Twelfth Century.” Art History (2001): 24(1), 17–50. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8365.00248

[xxxiv] Hoffman, “Pathways”, 18.

[xxxv] Hoffman, “Pathways”, 26.

Bibliography

Cutler, Anthony. “Gifts and Gift Exchange as Aspects of the Byzantine, Arab, and Related Economies.” Dumbarton Oaks Papers 55 (2001): 247–78. https://doi.org/10.2307/1291821.

Hoffman, E. R. “Pathways of Portability: Islamic and Christian Interchange from the Tenth to the Twelfth Century.” Art History (2001): 24(1), 17–50. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8365.00248

Ibn-al-Zubayr, Qāḍī ar-Rašīd, and Ghāda Ḥijjāwī Qaddūmī. Book of Gifts and Rarities: Selections Compiled in the Fifteenth Century from an Eleventh Century Manuscript on Gifts and Treasures = (Kitāb Al-Hadāyā Wa Al-Tuạf). Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ. Press, 1996.

Jacoby, David. “Silk Economics and Cross-Cultural Artistic Interaction: Byzantium, the Muslim World, and the Christian West.” Dumbarton Oaks Papers 58 (2004): 197–240. https://doi.org/10.2307/3591386.

Mackie, Louise W. Symbols of Power: Luxury Textiles from Islamic Lands, 7th-21st Century. Cleveland, OH: Cleveland Museum of Art, 2015.

Shepherd, Dorothy G. “A Dated Hispano-Islamic Silk.” Ars Orientalis 2 (1957): 373–82. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4629043.

Shepherd, Dorothy G. “A Twelfth-Century Hispano-Islamic Silk.” The Bulletin of the Cleveland Museum of Art 38, no. 3 (1951): 59–62. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25141697.

Shepherd, Dorothy G. “The Third Silk from the Tomb of Saint Bernard Calvo.” The Bulletin of the Cleveland Museum of Art 39, no. 1 (1952): 13–11. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25141758.

The Cleveland Museum of Art. “Fragment with eagles in roundels from the Reliquary of Saint Librada.” September 16, 2022. https://www.clevelandart.org/art/1952.15

The Cleveland Museum of Art. “Samite fragments with double-headed eagles, from the tomb of Saint Bernard Calvo.” September 16, 2022. https://www.clevelandart.org/art/1951.92.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art. “Textile Fragment with Double-Headed Eagles.” Accessed December 7, 2022 https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/468062?ft=islamic+silk&offset=0&rpp=40&pos=6

Unger, Richard W. “Commerce, Communication, and Empire: Economy, Technology and Cultural Encounters.” Speculum 90, no. 1 (2015): 1–27. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43577271.