The Ribat of Sousse Object Biography

Historical Context

The ancient city of Hadrumetum, present-day Sousse (Arab. Susa), holds the oldest surviving Islamic buildings in the world, namely in the walled city. Inside this fortress is the ribat at Sousse, an ancient structure sufficing as a defensive military architecture, a residential fortress, and eventually a religious institution.[i] Even the word “ribat” has a history of warfare tied to its meaning. Starting in the 7th century, the term meant the preparation of battle horses. By the beginning of the Abbasid rule, ribat meant “fortified building, a tower or a fort.”[ii] At the time of the ribats’ construction, the Aghlabids ruled the Ifriqiyan from 800-909. Historically called the “Aghlabid century,” the empire in Northern Africa flourished as a cultural center. Throughout this era, Aghlabid architecture drew inspiration from Roman, Byzantine, and Abbasid styles.[iii]

Although ribats are found all around the Middle East, the best known and most interesting are found in the Maghreb along the Tunisian coast.[iv] The Ribat at Sousse and other ribats along the coastline were within signaling distance of each other, creating a long line of coastal fortifications and defense in Northern Africa. The chain of military architecture stretched all along the southern shore of the Mediterranean from Ceuta to Alexandra. This allowed for an effective defensive strategy against the impending dangers of the Turkish and Byzantine empires and continued expansion into European territories.[v] These fortresses built on the coast of Northern Africa provided a defensive military structure for Muslim expansion into central Mediterranean regions. Specifically, the Muslim conquest of Sicily, led by Asad b. al-Furat in 827, was launched from Sousse, which later became a common base for such expeditions and conquests. The religious aspect of these fortresses comes into play in the consideration of the motivation behind Muslim conquests. In Islamic theology, one of Muhammad’s teachings is the idea of jihad, the “struggle for the faith” or “holy war” as an obligation of Muslims to defend their religion. There are explicit instructions from Prophet Muhammad to defend against the enemies of Islam and in the case of the Northern African coast, that involved a line of defensive ribats.[vi] Therefore, war was waged in order to expand or defend Islam. Eventually, Islamic marine warfare developed allowing for the Aghlabids in the ninth century to control the western Mediterranean and the Fatimids in the tenth century to dominate the eastern Mediterranean. Eventually, once the ribats no longer served the military or coastal defense system, they were considered sanctified religious sites and used mostly for teaching.[vii]

[i] Jonathan Bloom, Architecture of Islamic West (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2020), 25-28.

[ii] Stephane Pradines, “Coastal Fortifictions in 9th Century Tunisia and Egypt,” in Ports and Fortifications in the Muslim World (Le Caire, Institut français d'archéologie orientale, 2020), 53-64.

[iii] Philip Naylor, “Medieval North Africa,” in North Africa (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2009), 57-88.

[iv] Hugh Kennedy, “The Ribat in the Early Islamic World,” in Western Monasticism Ante Litteram (Tournhout: Brepols, 2011), 161-175.

[v] “Ribat of Sousse,” Qantara, accessed May 1, 2023, https://www.qantara-med.org/public/show_document.php?do_id=417&lang=en

[vi] Naylor, “Medieval North Africa,” 58.

[vii] Qantara, “Ribat of Sousse.”

Description of the Ribat at Sousse

The Ribat of Sousse was established in the eighth century under the governorship of Yazid b. Hatim al-Muhallabi (ruled 772-788) and rebuilt in AD 821 by an Aghlabid emir, Ziyadat Allah I. The purpose of the ribat was to stand as a fortified residence for the city’s ruler as well as for the defense of the arsenal. The ribat was inspired by elaborate Umayyad desert castles and the fortified Byzantine citadels. The fortress still has medieval fortifications preserved from 1,200 years ago! The Aghlabid military architecture is not a surprise to historians, as Sousse was the largest naval base in the region during the Aghlabid century. The ribat at Sousse is part of a greater fortified city that includes a citadel, two watchtowers, and a fortified mosque, all encompassed by a city wall. The fortified city of Sousse was equipped with an arsenal as well as an indoor harbor.[i]

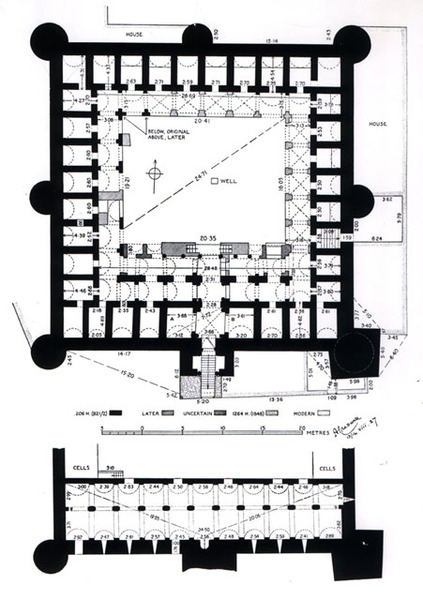

The various parts of the city were added throughout history under different governors and empires, but one of the earliest structures was the ribat. This large defensive military structure has a carved stone architectural pattern and was constructed from shelly sandstone granite, marble, wood, and rubble stones. The large square stone building stands approximately 11 meters high with 40-meter-wide walls, with three shorter towers in three corners and a tall guard tower in the southeast corner.[ii] Each side, but the south, has half-round towers in the middle. The south wall has the only entrance into the fortress; a slight horseshoe shape doorway resting on two repurposed Corinthian columns. In fact, much of the building materials were reclaimed from older buildings of Antiquity, specifically columns and capitals from previous Roman temples.[iii] The inside of the ribat has vaulted hallways lined with cells and large vaulted rooms throughout the structure. The vestibule includes a mihrab wall, suggesting that this room served as a mosque, at least until the congregational mosque was built nearby in 851. The entrance vestibule is flanked by defensive guardrooms.[iv] The ground floor has a courtyard surrounded by porches overlooking storerooms. The first floor has three wings of dormitory residences and a fourth wing consisting of a mosque. The military infrastructure included some aspects of direct combat as well. The ribat has slits in the stone ceiling above the entrance that allowed for a defensive strategy where soldiers could drop stones, boiling oil, or even toxic substances from above. These slits were suggestively called murder holes throughout history.[v]

[i] Pradines, “Coastal Fortifications,” 53.

[ii] Pradines, “Coastal Fortifications,” 53.

[iii] Miklos Kazmer, “Repeated historical earthquakes in Sousse, Monastir, and El-Jem (Tunisia) – an archaeoseismological study,” Arabian Journal of Geosciences 14, no. 1 (February 2021): 214, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12517-020-06372-w

[iv] Bloom, Architecture, 25.

[v] Pradines, “Coastal Fortifications,” 53.

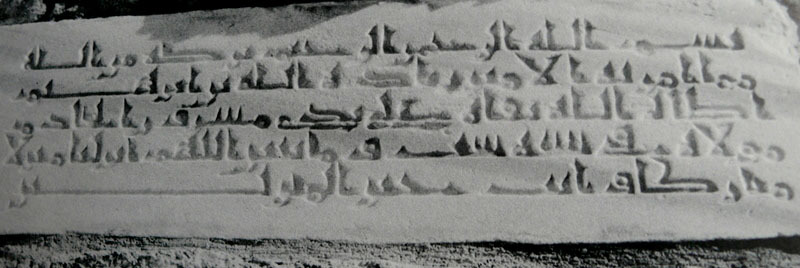

Further inside, two flights of stairs lead up to the roof lined with battlements on both the court-side and exterior of the fortress walls. The cylindrical watchtower in the southeast corner stands 16 m high from the roof. Over the entrance of the spiral staircase is an incised marble plaque with an inscription explaining the addition of the guard tower contributed to Aghlabid ruler Ziyadat Allah b. Ibrahim in 821 and his architect Masrur.[i] The builder, Masrur al-Khudim was the emir’s emancipated slave. Also included in the inscription is the Throne verse from the Qur’an: “And say, ‘My Lord! Make my landing a blessed landing, for You are the Best of those Who can cause people to land in safely” (Qur. XXIII, 29).[ii] This plaque is the oldest surviving monumental inscription in Tunisia! The longevity of the preservation of not only the guard tower’s inscription but the ribat itself is a great example of the extravagant history of Sousse and Islam in Northern Africa.[iii]

Another important monument of the Medina at Sousse is the Kasbah (also known as the Khalaf tower), which was built in service of Prince Zidayat Allah I and dedicated to Abu al-‘Abbas Muhammad. The tower, which stands 77 meters above sea level, was built during the construction of the medieval ramparts dated by an inscription in 859. Unlike the spiral staircase found in the Ribat’s guard tower, the Khalaf tower contains four rooms and a small mihrab. There is a staircase that leads up through the tower to the ramparts and another flight of stairs on the third floor that lead to a small chamber and the roof. The ramparts, although consistently repaired and rebuilt throughout history, are made of stone, which is an uncommon material at the time. Elsewhere in Northern Africa, city walls were built of mud, pise, or brick.[iv]

[i] Bloom, Architecture, 27.

[ii] 7 Qu’ran

[iii] Qantara, “Ribat of Sousse.”

[iv] Bloom, Architecture, 27.

The Ribat at Monastir

Although a unique structure, the ribat at Sousse is not the only of its kind. A couple of miles south stands the ribat at Monastir, founded in 796 by Abbasid governor Harthama ibn Ayun. The great ribat of Monastir, or al-Qasr al-Kabir, has a very similar layout to that found in Sousse. Monastir is also a square building with three round towers and one tall watchtower in the southeast corner. There is some controversy about which ribat is older; originally, Monastir was much smaller than the ribat at Sousse and has undergone many renovations and reconstructions.[i] The core of the structure was built during the Abbasid dynasty in AD 796. In the 9th century, the Aghlabids added two barracks and, in the 10th, and 11th centuries the Citadel was enclosed with a curtain wall and two square towers4 Modifications to the physical structure and the function of the building continued into the 20th century.[ii] Although filled with pious inhabitants, and even noted as a religious retreat, Monastir was without a doubt a military building.

Understanding the Ribat's Extravagance

The clear connections between military and spiritual functions at these earliest ribats are a unique use of space in ancient Islam. Although it is difficult to know how common the military uses of the ribats at Monastir and Sousse were across the early Islamic World, their unique geographical location made their lavish history full of warfare stories and military conquests and defenses. Not to mention the complicated mix of religious and military uses of these buildings throughout history. Another unusual aspect of these ribats is their mixed history of reconstruction and preservation, making the ancient accounts of these buildings both extravagant and fascinating. The ribat at Sousse is a remarkable monument for many reasons but especially the extravagant documentation of construction throughout its history. The many plaques and inscriptions describing the construction of various parts of the city are unusual at that point in Islamic history.[i] Although a simple structure at first glance, the intersectionality of uses, the various cultural inspirations, the many geographical influences, and the longevity of its preservation, prove that the Ribat of Sousse is far more extravagant than it seems.

[i] Kennedy, “Ribat,” 163.

Works Cited

Bloom, Jonathan. Architecture of Islamic West. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2020.

Haleem, Adbel. Qu’ran. New York: Oxford University Press, 2004.

Kazmer, Miklos. “Repeated historical earthquakes in Sousse, Monastir, and El-Jem (Tunisia) – an archaeoseismological study.” Arabian Journal of Geosciences 14, no. 1 (February 2021): 214. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12517-020-06372-w

Kennedy, Hugh. “The Ribat in the Early Islamic World.” In Western Monasticism Ante Litteram, 161-175. Tournhout: Brepols, 2011.

Naylor, Philip. “Medieval North Africa.” In North Africa, 57-88. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2009.

Pradines, Stephane. “Coastal Fortifications in 9th Century Tunisia and Egypt.” In Ports and Fortifications in the Muslim World, 53-64. Le Caire: Institut français d'archéologie orientale, 2020.

Qantara. “Ribat of Sousse.” Accessed May 1, 2023. https://www.qantara-med.org/public/show_document.php?do_id=417&lang=en