Book of Curiosities Catalogue Entry

Mapmaking in the Islamic paradigm has long been misunderstood, misinterpreted, and under-intellectualized. The discovery of the Book of Curiosities of the Sciences and Marvels for the Eye in 2003 could be considered a milestone in turning the tide of misinformation surrounding Islamic art. Two books full of maps of the universe and the Mediterranean Sea from the perspective of the Fatimid empire have provided profound amounts of information towards Islamic cartography as not just cartography but works of art and history: “…every map displays a specific world; so does it display the world as it is, as it was, as it will be, as it could be, or as it should be? Each of these possibilities implies a specific view of the map and specific intellectual operations”1.

The development of Islamic cartography is not similar to other cartographic trends, especially those of medieval Europe. Earlier Islamic maps are actually more mimetic than later ones, which strongly supports the idea of maps as contextual evidence rather than strictly navigational tools4. Scholar Zayde Antrim proposes that Islamic maps should never be analyzed on their own, “even when they appear in stand-alone form, but must always be situated within their political and cultural milieu and in dialogue with related geographical discourses” 5. There were also artistic choices that made these maps easy to disseminate. The pigments of many original maps were made of precious metals and stones, but the designs themselves were easy to replicate which allowed rulers to transmit the information in the map to rural or unconnected parts of their empire6. The intentional ease of dissemination emphasizes the artistic design of the map and how it conveys a message rather than taking the map as its own object. Historically, this aspect of Islamic cartography has been overlooked: “On the one hand, the specialized study of Islamic maps has largely been taken up by historians of science, whose main focus has traditionally been mathematical precision and methods of projection, often at the expense of the social and political context in which the maps were produced”7. As time goes on and Islamic autonomy is slowly restored in light of centuries of orientalism, it becomes clear that Islamic cartography and literature have just as much meaning as has been attributed to the same European fields.

The Book of Curiosities of the Sciences and Marvels of the Eyes is a fantastic case-study for the theme of maps as contextualizing pieces of art for many reasons, not the least of which include the book’s strong ties to Fatimid maritime activities and oldest-surviving map of Cyprus, a non-Muslim occupied island in the Mediterranean. To begin, its author is unnamed, but throughout the treatise repeatedly identifies himself under the rule of the Fatimid caliphate8. The treatise is made up of two books, the first on cosmology and its influence on the Earth, and the second on the Earth itself. This differs from other cartographical traditions at the time, Islamic and non-Islamic alike. The second book of the treatise is more heavily studied because of revolutionary information it provides about “an otherwise-lost medieval Islamic view of the world”9. The ideals and priorities of the Fatimid caliphate are evident throughout both books of the treatise, especially considering bodies of water and rivers as the framing pieces of almost every map in the second book. At the time of the creation of the treatise, the Mediterranean was a becoming a major player in the expansion of the Fatimid Islamic empire: “More than previous Islamic empires, the Fatimids relied on naval power and maritime commerce to pursue their political and religious ambitions”10. The undefined coastlines, focus on labeling seaports over landmarks, and overall representations of land were all meant to support a view of the Mediterranean region from the sea, as the Fatimid mariners would have seen it. The broad coastlines in many Islamic maritime maps were meant to make it easier for the mariners to direct themselves simply on the coastline instead of the winds11. There is even an entire chapter of the Book of Curiosities devoted to non-Muslim occupied islands in the Mediterranean and Indian Oceans titled “Islands of the Infidels"12 . These maps would have been particularly import to the Fatimid ruler and his envoy as they planned their expansion across the region.

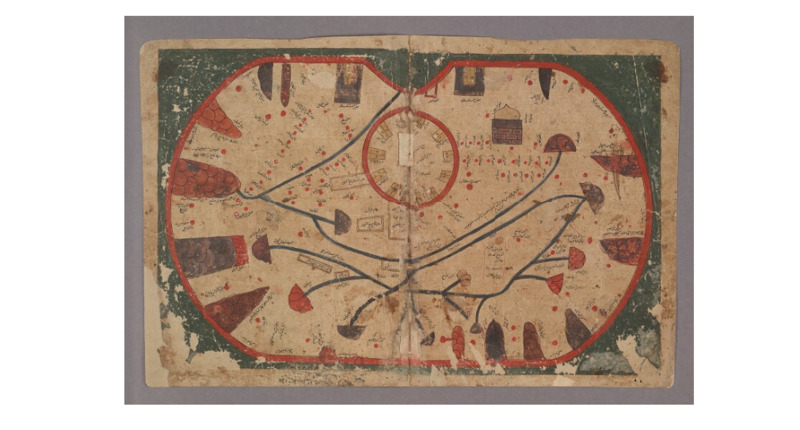

The second book of the Book of Curiosities is filled with revolutionary maps of the medieval-era world. One particularly significant finding is the earliest known map of Sicily, an island off the coast of Italy. This map portrays a large number of the themes seen generally through the Book of Curiosities, including abstracted coastlines, a design made for storytelling over exact representation, and very specific landmarks important to the Fatimid polity in the area. In terms of significance to the larger work of the Book of Curiosities, Sicily being under Muslim rule is what allowed rulers to date the original treatise, as it must have been before the Norman invasion in 106813. Geographically, Sicily is triangular. The mapmakers choice to represent the island instead as an oval indicates its significance as a maritime port as it would be seen from the water, further proven by the round indentation at the center-top of the map representing the port of Palermo. The “onion-domed building” below and to the right of the port of Palermo is the palace of the Sultan. The 11 thorn-like structures lining the interior of the round walls guarding the island are each a gate into the city14. Each of these features supports the political culture of the Fatimid empire as one of power and intellect. Further, “…the walls of Palermo, the towers and the palace are bloated out of proportion and with no attention to scale…” 15. It is undeniable that the artist behind this map had political and social motivations to represent the established and durable Fatimid presence on Sicily.

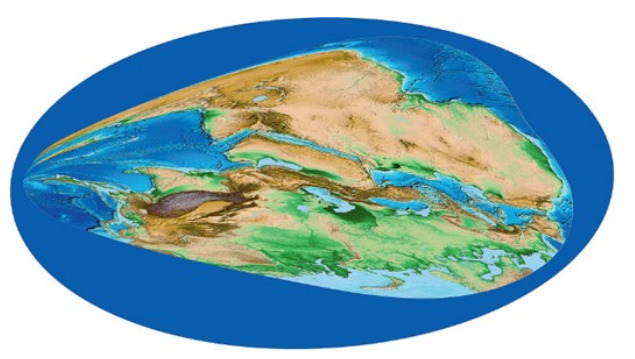

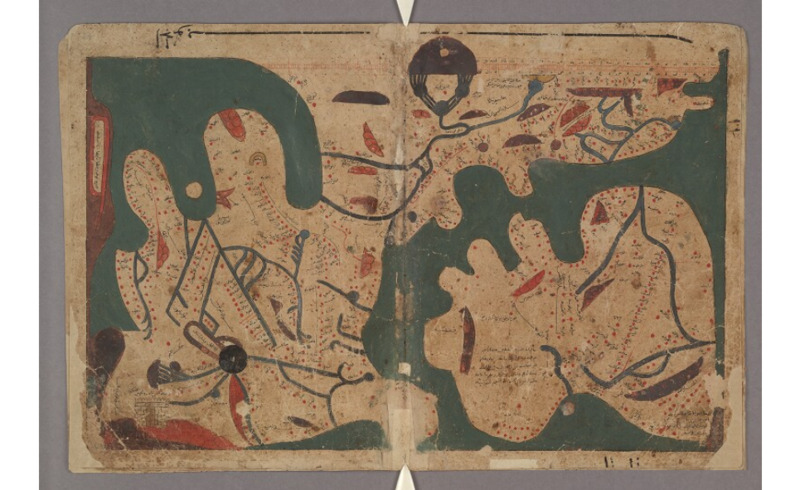

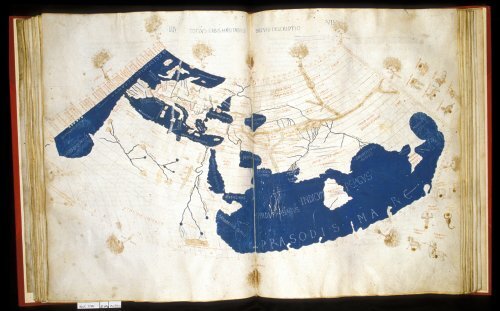

A second especially important map in the Book of Curiosities is the only rectangular map of the world from the medieval era. Once again, its coasts are only mimetic in the most general sense, but in the text accompanying the piece, the author addresses this and explains that he wanted his map to be accurate even as the coast changes over time, as well as facilitating his labeling of the coastal cities as they would be seen from the water by the mariners 16. Apart from being the only rectangular map from antiquity, the world map also has a scale for distance that is generally out of place in other Islamic maps. This scale is another reminder of this treatise being a copy as the markings are not correct and don’t follow the whole length of the scale. This may be because the artist who was reproducing the treatise was misreading it as he copied, recognized his mistake, and had to give up on finishing it. In combination, the rectangular shape and the scale “requires that full account be taken of the possibility that it might in some way reflect the early ninth-century map made for Ma’mùn, or even the much earlier projection of Marinus of Tyre, as described by Ptolemy”17. A recreation of the map the authors are likely referring to has been shown for comparison.

1Jacob, Christian, “Toward a Cultural History of Geography”, Imago Mundi 48, no. 1 (1996), pp 95.

2Karen C. Pinto, “KMMS World Maps Primer” in Medieval Islamic Maps: An Exploration, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, November 2016, pp 62.

3Pinto, Medieval Islamic Maps, 59.

4Pinto, Medieval Islamic Maps, 66

5Zayde Antrim, Mapping the Middle East, London: Reaktion Books, 2018, pp 12.

6Pinto, Medieval Islamic Maps, 2.

7Yossef Rapoport, Islamic Maps, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2020, pp 7.

8Rapoport, Islamic Maps, 68.

9Rapoport, Islamic Maps, 69.

10Rapoport, Islamic Maps, 73.

11Kahlaoui, Tarekm “The Maghrib's Medieval Mariners and Sea Maps”, Journal of Historical Sociology vol. 30, no. 1 (March 2017).

12Rapoport, Islamic Maps, 76.

13Rapoport, Islamic Maps, 69.

14Rapoport, Islamic Maps, 66.

15Rapoport, Islamic Maps, 67.

16Jeremy Johns and Emily Savage Smith, “The Book of Curiosities: A Newly Discovered Series of Islamic Maps”, Imago Mundi: International Journal for the History of Cartography 55, no. 1 (October 2003), pp 12.

17Johns and Savage Smith, 13.

Antrim, Zayde. Mapping the Middle East. London: Reaktion Books, 2018.

Jacob, Christian, “Toward a Cultural History of Geography”, Imago Mundi 48, no. 1 (1996), pp 95.

Johns, Jeremy and Emilie Savage-Smith. “The Book of Curiosities: A Newly Discovered Series of Islamic Maps.” Imago Mundi: International Journal for the History of Cartography 55, no. 1 (October 2003): 7 – 24. https://doi.org/10.1080/0308569032000095451.

Kahlaoui, Tarek. “The Maghrib's Medieval Mariners and Sea Maps: The Muqaddimah as a Primary Source.” Journal of Historical Sociology 30, no. 1 (March 2017): 43 – 56. https://doi.org/10.1111/johs.12150.

Pinto, Karen C. “KMMS World Maps Primer” in Medieval Islamic Maps: An Exploration, 59 – 78. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, November 2016.

Rapoport, Yossef. Islamic Maps. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2020.