Polo Glass Bottle Catalogue Entry

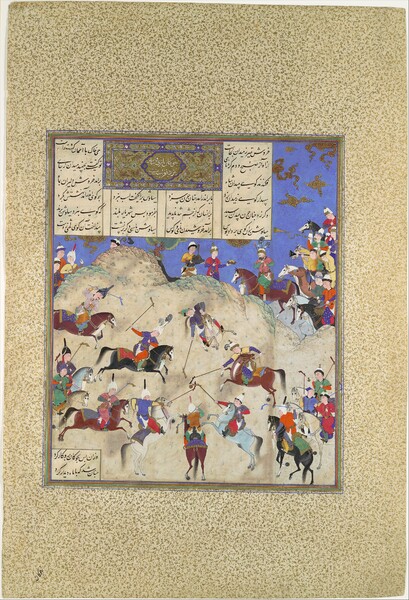

Polo is said to have originated in Iran, although there were similar equestrian games played by Turkic and Iranian nomadic tribes. For example, in the area of present day Afghanistan, there was a game called buzkashi where horseman fight for possession of a goat carcass, and whoever is able to get the carcass to the other side of the field gets a point. Pakistan also has a form of polo that is still played today, but the most widely played version can trace its roots back to the Parthian dynasty in north-eastern Iran. The earliest mention of polo was in the early 7th centaury in a text about Ardashir, the founder of the Sasanian dynasty, called Karnamak-e Ardashir-e Papakan. In this text, which takes place in the 3rd centaury, Ardashir plays against the Parthian king Ardavan V and his sons. The game was also popular with the Sasanians after the Parthians fell. When the Muslim caliphate took over the Sasanians, polo continued to thrive and was popular in many Islamic states such as the Umayyads, Abbasids, Safavids, Ayyubids, Mamluks, and Ottomans.[1]Interestingly enough, polo was not played in Islamic Spain.[2] Additionally, Polo spread to the Byzantine Empire, and to the Turks and Mongols who conquered Iran. The Silk Road helped bring polo to China, where it was also hugely popular. The Mughals brought polo to the Indian subcontinent,[3] and then later on the British colonialists brought the game to Western Europe, although there are multiple accounts from European travelers encountering polo throughout the Islamic world.[4]

Throughout its lifetime, polo was mostly enjoyed by the nobility and rulers, and in some instances, women might have also played polo. The Sasanian king Khosrow II is said to have met his wife Shirin when she was playing polo with her friends. He was impressed by their strength and even played a match against them.[5] There have also been multiple works of art from China, such as terra cotta sculptures, that portray women playing polo.[6] Although polo was a game meant for leisure, it was also often used to show the ability of rulers, military leaders, and other nobility. The Sasanian king Khosrow II even hires a nobleman for a position in office at the court purely because the nobleman was a talented polo player.[7] Stories of kings, princes, and heroes, even the purely mythical ones or those who were said to be alive before polo was invented, playing polo occurs multiple times in the Shahnameh. The Shahnameh even has the first international polo match between the Turanian king Affrasyib and the Iranian price Siavosh.[8] Polo was one way that rulers proved themselves, but some have lost the throne due to this game. Some injuries, like blindness, can cause a person to be deemed unfit to rule. Some players have also lost their lives due to injuries resulting from the game.[9] In addition to the danger, both scholars of Islamic law and Confucian scholars were morally opposed to polo.[10] Despite this, polo continued to be a central part of court life in the Islamic world as well as a major part of the culture. For example, not only is it included in the Shahnameh, it is also mentioned in A Thousand and One Nights and is the subject of multiple poems.[11]

The Glass Bottle with Polo Players is an enameled and glided glass bottle from the Mamluk era. It stands at 28 centimeters tall with a diameter of 19 centimeters. The glass itself is a pale yellow color which is characteristic of Mamluk glass. There is an inscription on the neck of the bottle, as is common with Mamluk glass, but the inscription is just general praise and does not further specify for whom, why, where, or when this bottle was made. The main frieze on this bottle depicts twelve figures on horseback playing polo, as indicated by some of the figures holding polo sticks. There is another frieze above the polo player frieze, which depicts dogs, rabbits, and bears running. This frieze is interrupted by 3 red rosettes with white backgrounds. Above the animal frieze, there are three birds placed around the bottle. Little is known about the life and function of this piece. It is unclear whether this bottle originated in Egypt or Syria, since the Mamluks had major glass workshops in both places and the inscription does not give information about the creator. The rosettes do give the clue that it was commissioned by a Rasulid ruler, since other pieces commissioned by Rasulids have similar rosettes on them. The bottle somehow made its way from the Rasulids to China, which was not unusual for works of Mamluk glass, and in 1913 it was purchased to be part of the private collection of Count Friedrich von Pourtalès, who was the German ambassador to Russia.[12] Today, it is at the Pergamon Museum in Berlin.

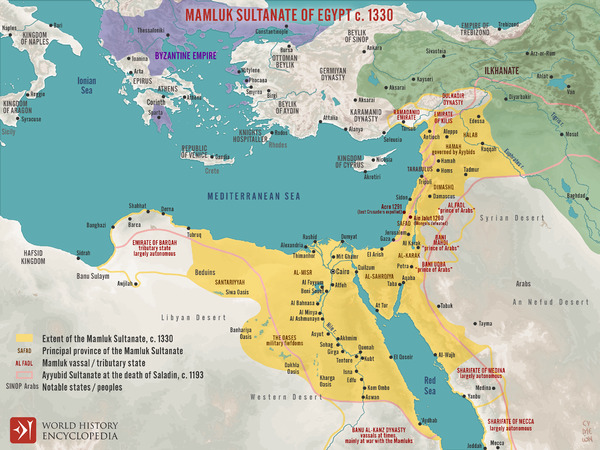

The Mamluk dynasty was a sultanate that ruled over present day Egypt, Syria, and part of Saudi Arabia from the 13th to 16th centauries. They are perhaps most well known for their enameled glass, which they controlled the production of until the late 15th centaury when the majority of glass production shifted to Venice for political and economic reasons. Even though there were some pieces made directly for nobility or mosques, the glass was also commercial.[13] They were often made in large quantities and sold at bazaars.[14] The Mamluks’ biggest workshops for enameled glass were in Damascus, Aleppo, and Cairo. However, in the 14th century when Cairo was becoming one of the most important cities in the Mamluk sultanate, most enameled glass was attributed to Cairo rather than Damascus and Aleppo.[15] The making of glided and enameled glass was a difficult process. The glass object was made, then painted, and then heated in the kiln again for the paint to bake into the glass. However, because of different chemical properties, each color required a different temperature. This situation was problematic since reheating of the glass for each color of paint could cause the glass to deform. The Mamluks were able to devise a technique where all the paint was applied and heat all at once without the paint smearing or the glass deforming. This technique is what gave the Mamluks control over glass.[16]The early decoration of the glass started as figural and colorful and eventually shifted to be more vegetal and had fewer colors. The preferred objects to make became bigger as well. Earlier samples of gilded glass were mostly things like bottles, bowls, and beakers. As time went on, objects like lamps, vases, and decanters became more and more common. However, the glass itself being a yellow or brown color was a consistent characteristic of Mamluk glass, which unfortunately has caused some people to disregard the work as low quality.[17]

TIntact works of Mamluk enameled glass are hard to come by, however at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, there is a similar bottle to the Polo Player Bottle that was created around the same time frame. This bottle has one frieze that depicts Arabic and Mongol warriors fighting on horseback with 3 large medallions on the shoulder of the bottle and a phoenix on the neck. Figures on horseback were common images on early Mamluk glasswork, as shown by both of the bottles, which shows the importance of equestrianism in the society. The glass of the Warrior bottle is a brown color, but as mentioned before that is also common in Mamluk glass. The warrior bottle has some Chinese influence on it as shown by the phoenix, cloud motifs, and gold scrolls on the neck.[18] Both of these bottles can be contrasted with the Footed Bowl with Eagle Emblem, which although comes from an earlier time than the bottles is actually more aligned with the color palette of later Mamluk glasswork. There is enameling and color work on the bowl , but the use of color is more restrained and the colors are less contrasting, especially when compared to the Warrior bottle. The Polo Player bottle is also less colorful than the Warrior bottle but the focus is still on the enameled frieze unlike the footed bowl where the focus is mainly on the gliding.[19] The footed bowl has figural imagery such as dogs and musicians, so it is not completely in line with the norms of later Mamluk glasswork. The bowl is also a similar shape to a Christian chalice, and Christian themes and influence were also something that was characteristic of earlier Mamluk work.[20] The Mosque Lamp for the Mausoleum of Amir Aydakin al-'Ala'i al-Bunduqdar is also from the same time frame as the 2 bottles. It employs the same use of color as the bottles. However, since it was a piece of art for a religious setting there is no figural images except for the nine bow emblems around the lamp. Since this lamp was for the tomb of a high ranking official, the bow emblem, which is 2 gold bows against a red background, could symbolize the position that Aydakin had, which was the Keeper of the Bow for the sultan.[21]

[1] H.E Chehabi and Allen Guttman, “From Iran to All of Asia: The Origin and Diffusion of Polo,” International Journal of the History of Sport 19 (2002):384-388.

[2] Horace Laffaye, “Folk Games: From the Slik Road to the Manipuri Valley,” in The Evolution of Polo (Jefferson: McFarland and Co, 2009), 6.

[3] Chehabi and Guttman, “Origin and Diffusion of Polo,” 392.

[4] Laffaye, “Folk Games,” 10.

[5] Chehabi and Guttman, “Origin and Diffusion of Polo,” 389.

[6] Laffaye, “Folk Games,” 9.

[7] Chehabi and Guttman, “Origin and Diffusion of Polo,” 385.

[8] Chehabi and Guttman, “Origin and Diffusion of Polo,”388.

[9]Chehabi and Guttman, “Origin and Diffusion of Polo,” 386.

[10] Chehabi and Guttman, “Origin and Diffusion of Polo,” 391, 395.

[11] Chehabi and Guttman, “Origin and Diffusion of Polo,”388-391.

[12] Jens Kröger, “Bottle with Polo-Playing Riders,” Museum with No Frontiers, published 2023, accessed April 2023, https://islamicart.museumwnf.org/database_item.php?id=object;ISL;de;Mus01;33;en

[13]Qamar Adamjee and Stefano Carboni, “Enameled and Gilded Glass from Islamic Lands,” Helibrunn Timeline of Art History, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2002, accessed April 2023, https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/enag/hd_enag.htm.

[14] Maurice Dimand, “An Enameled-Glass Bottle of the Mamluk Period,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 3, no 3 (November 1944): 73, https://doi.org/10.2307/3257229.

[15] Stefano Carboni, “Painted Glass,” in Glass of the Sultans, ed. David Whitehouse and Stefano Carboni (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001), 205

[16] Adamjee and Carboni, “Enameled and Glided Glass.”

[17] Carboni, “Painted Glass,” 199-207.

[18] Dimand, “Glass Bottle of Mamluk,” 74-75.

[19] Dimand, “Glass Bottle of Mamluk,” 76.

[20] Carboni, “Painted Glass,” 207.

[21] Carboni, “Painted Glass,” 228-230.

Works Cited

Adamjee, Qamar, and Stefano Carboni. “Enameled and Glided Glass from Islamic Lands.”

Helibrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2002, accessed April 2023. https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/enag/hd_enag.htm.

Carboni, Stefano. “Painted Glass.” In Glass of the Sultans, edited by Stefano Carboni and David

Whitehouse, 199-273. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001.

Chehabi, H. E., and Allen Guttman. “From Iran to All of Asia: The Origin and Diffusion of

Polo.” International Journal of The History of Sport 19 (2002): 384-400.

Dimand, Maurice S. “An Enameled-Glass Bottle of the Mamluk Period.” The Metropolitan

Museum of Art Bulletin 3, no. 3 (November 1944): 73-77. https://doi.org/10.2307/3257229

Kröger, Jens. “Bottle with Polo-Playing Riders.” Discover Islamic Art, Museum with No

Frontiers, 2023, accessed April 2023. https://islamicart.museumwnf.org/database_item.php?id=object;ISL;de;Mus01;33;en.

Laffaye, Horace A. “Folk Games: From the Silk Road to the Manipuri Valleys.” In The

Evolution of Polo, 1-10. Jefferson NC: McFarland and Co., 2009