Alice Brown

Alice Brown was born on December 5th, 1856 on a farm in Hampton Falls, New Hampshire. She was the second child and only daughter of Levi and Elizabeth Lucas Robinson Brown (Lambert). She attended and graduated from Robinson Seminary in Exeter in 1876. While at seminary, she showed a talent for writing and often, other students and faculty enjoyed listening to her read her "literary exercises" on Friday afternoons. After seminary she went on to teach for five years, first in New Hampshire and then later in Boston but found that she disliked the profession and so turned to editing. She first worked at the Christian Register then at the Youth's Companion. By 1884 she published her first novel, Stratford-by-the-Sea and so began her long career as a writer, novelist and playwright. She lived in the Boston for the rest of her life, but spent summers in Newburyport, Massachusetts and at her farm in Hill, New Hampshire. She quickly became a part of the Boston literary scene and spent time with writers such as Louise Imogen Guiney, William Dean Howells, Thomas Wentworth Higginson, Annie Fields and Robert Frost. One of these writers she found a particularly close companionship with was Louise Imogen Guiney. They became quick friends that helped to spur each other’s creativity and remained close even after Guiney went to live in England permanently in 1901. Guiney and Brown traveled to England together where they walked and toured through the English countryside. Afterwards, they formed the Women's Rest Tour Association where they encouraged other women to "take their vacations with pack and stick in foreign lands". They maintained correspondence until Guiney died in 1920, after which, Brown wrote a sympathetic account of her life and literary career. Unfortunately, all of the letters between the two were burned.

The majority of Alice Brown's short stories are her New England stories where she reveals a mystical outlook on the natural world. Her experience of life on a New Hampshire farm in the late 19th century gave her ample material for her works. With these experiences she was able to show a deep understanding of the people who live in such environments and the powerful feelings they harbor. Feminist themes arise in her works and she creates a number of revolutionary feminist characters. She frequently writes of middle-aged women who fight for a greater sense of independence and confidence. These women characters often face a conflict between societal expectations and their own deepest desires, but bring about solutions to these conflicts and make their lives more meaningful through unconventional choices (Lambert). She also dealt with the issue of contemporary economic problems and believed the solution lie in individual action with moral and spiritual change, as opposed to economic or political solutions. The themes of old-age, the conflicts that arise out of old-age, as well as the supernatural are frequently played out in her fiction. In her works she shows the dilemmas that plague artists, such as the issue of writing things with true literary merit versus writing for reputation. She also shows the artist in old age, which results in fear of the aging process and a loss of creative power (Lambert). She also attempted to produce a play called Children of the Earth, A Play of New England. She won the Winthrop Ames prize for the play and it was produced on Broadway in 1915 but it was unpopular. Despite this disappointment, she went on to publish One Act Plays in 1921 and Charles Lamb: A Play in 1924. Throughout her life as a writer she produced a novel at least almost every other year, but Guiney claimed that Brown only published one third of what she actually wrote (Lambert). By 1915, her reputation was in decline and she never gained the reputation as a playwright that she had hoped for. From the 1890s to World War II she was a renowned writer in the Boston literary world but by the time of her death in 1948 she was mostly forgotten and her works went out of print. Deborah Lambert, in her article, "Alice Brown", states a few possible reasons for her abandonment as the sheer size of the literature she produced, the sentimentality in works, her mid-Victorian optimism and her rejection of modern ethos.

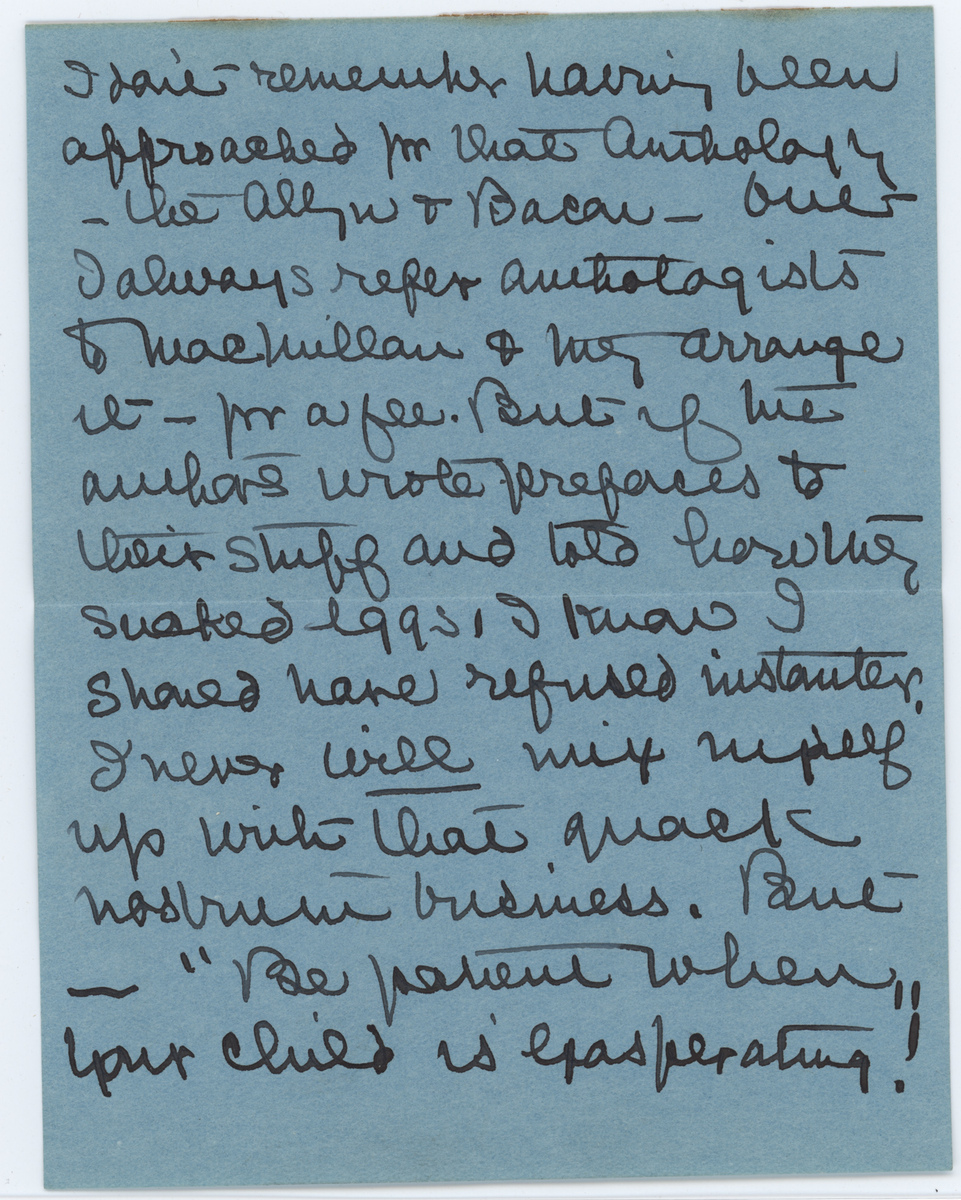

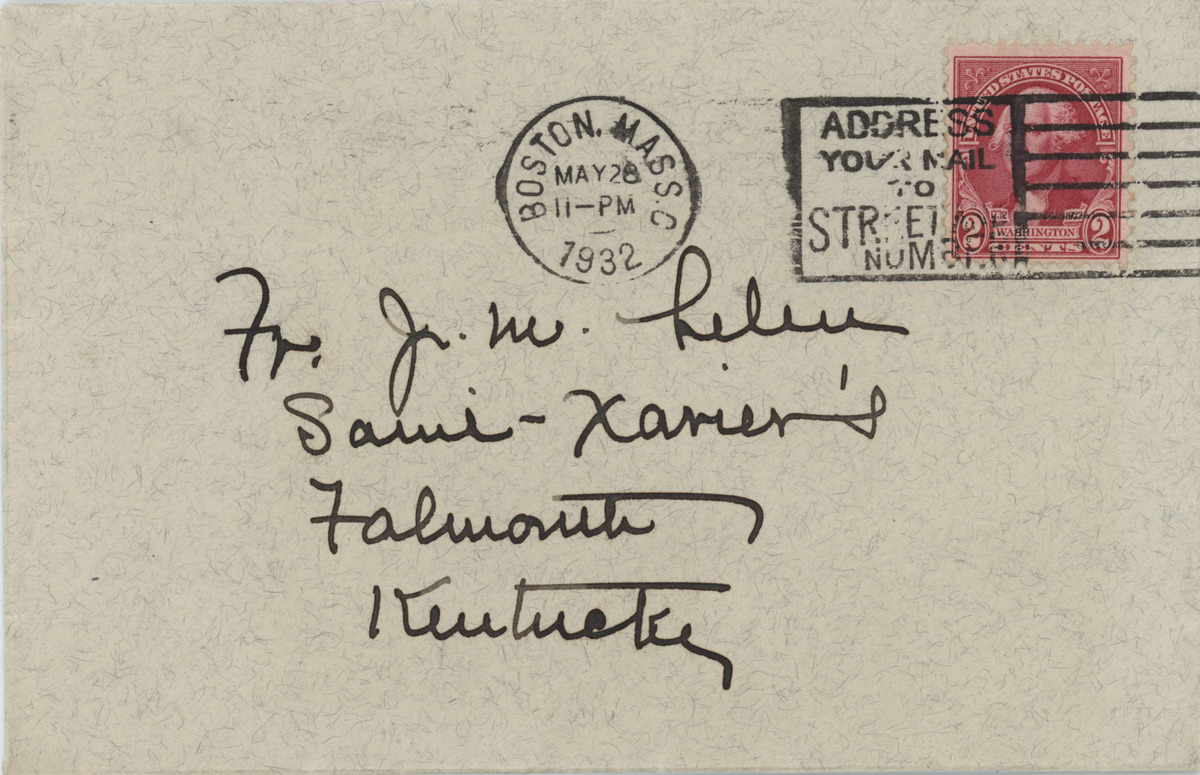

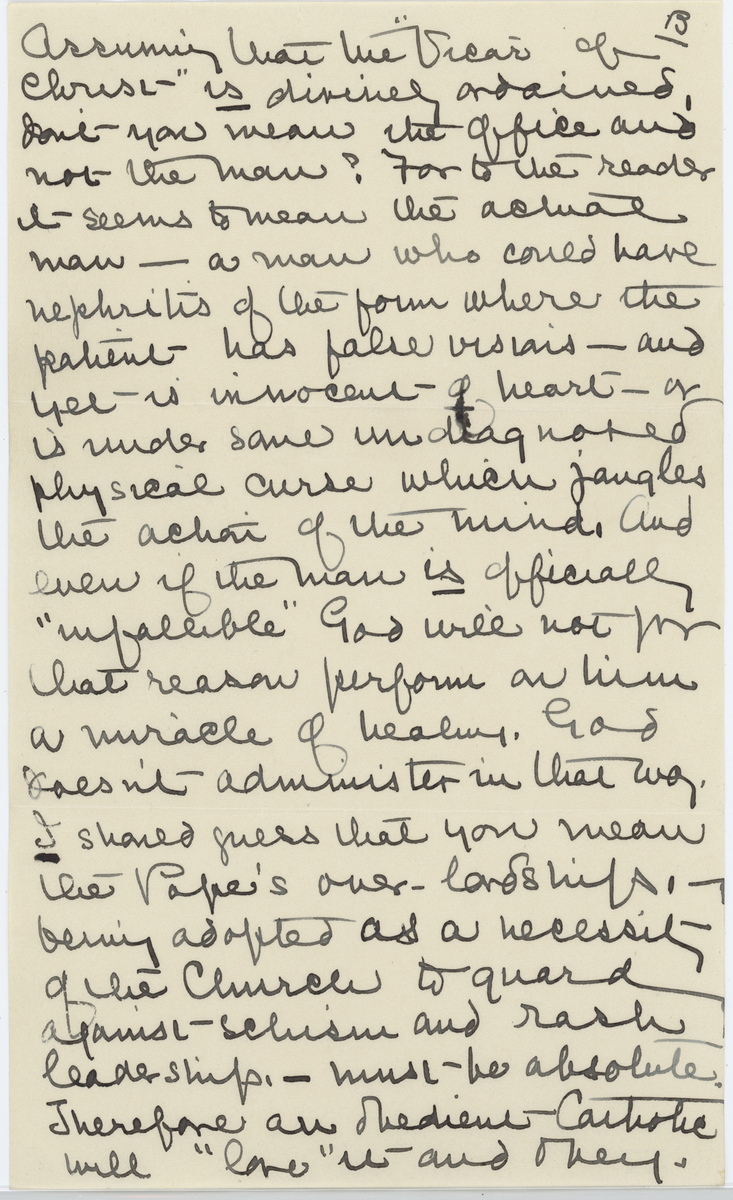

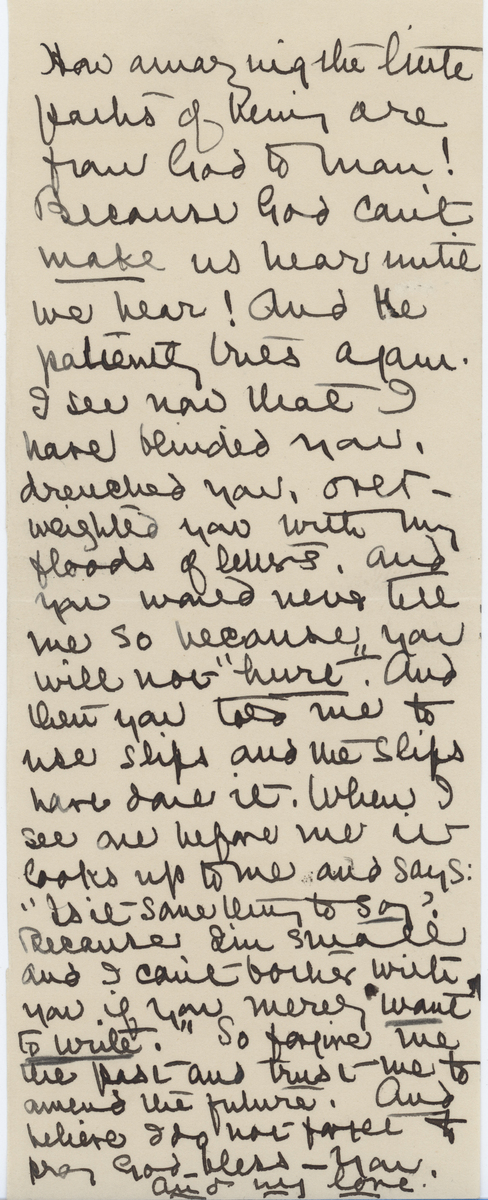

Letter 1 is just one of many correspondences between Alice Brown and Father Lelen. Fr. Lelen was a great author, poet, translator and philosopher who had connections with many notable and literary figures. In this brief note she reveals deep concern over Fr. Lelen's health since she has not heard from him lately. Letter 2, another letter to Fr. Lelen, was sent on May 28, 1932, after years of prior correspondence. She writes of a letter she found from Fr. Lelen while he was living in Falmouth, Kentucky as pastor of Saint Francis Xavier Church and claims, "That was written in the dark ages of the First Letters." Her letter is full of playful banter but always ensures to take care of his well-being. For example, she writes, "If anything in my letter hurts you, do not let it," and "...I can bear everything but your being tired." She then briefly discusses a request to include her in an anthology. She ends the letter, like many others, with no signature. Instead she ends with a piece of advice for Fr. Lelen in a quote, "Be patient when your child is exasperating!". Both Letter 3 and Letter 4 are unaddressed and also unsigned, but commonly discuss her faith and spiritual life. In Letter 3, she questions the infallibility of the Pope and his position as "divinely ordained". She seems dissatisfied at the end of her letter having only reached the conclusion that, "...an obedient Catholic will "love" it and obey". In Letter 4, Brown is clearly addressing someone, it is just unclear as to whom she is addressing. She starts off briefly discussing the greatness of God and the effort He puts to gain our attention. She apologizes for sending a "flood" of letters and talks about her new method of writing on "slips" of paper instead of full sheets. She questions whether she can truly "write" on these mere slips of paper. She closes by asking forgiveness and promising to pray. Letter 5 is unaddressed as well but a note on the back of the letter tells that she was writing about her dear friend, Louise Imogen Guiney. She read Guiney's poetry, "Whistles of Silver" and gave it high praise. However, ensuring no blind admiration, she argued that her writing was a little "swamped by her learning and the things so interesting to her". Both authors were pleased to get to know one another and gain from the other's experiences and talents.

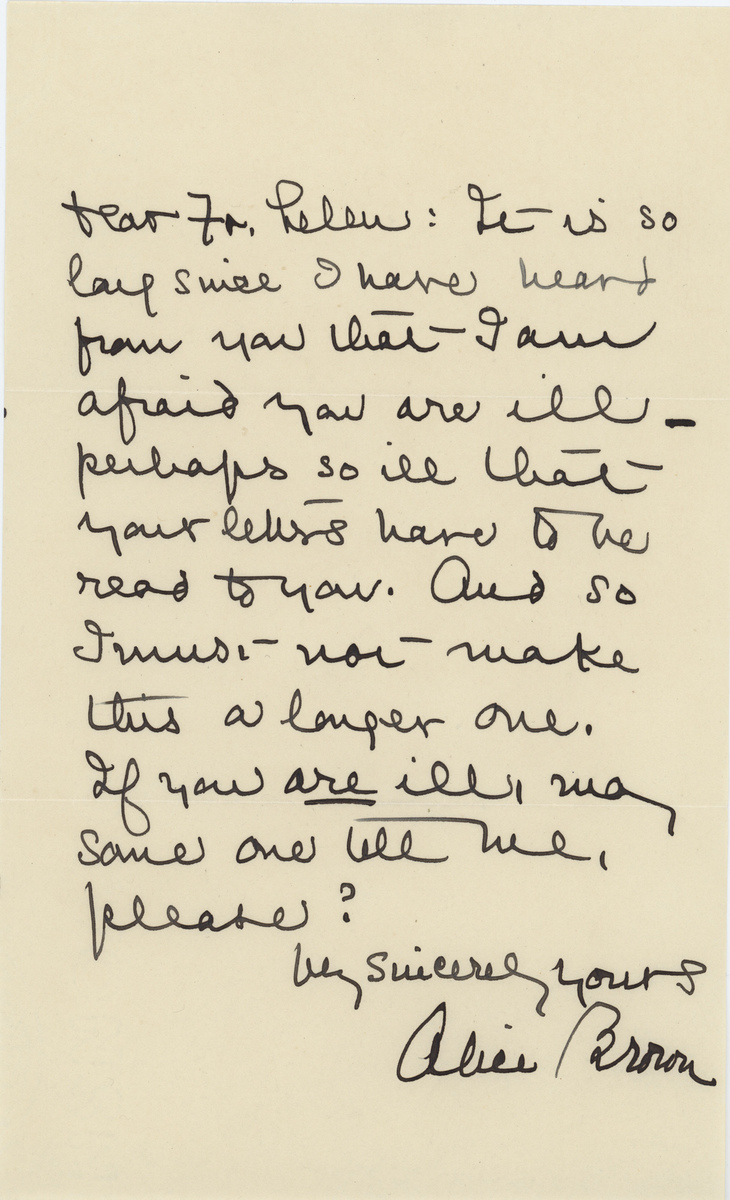

Letter 1

Dear Fr. Lelen: It is so long since I have heard from you that I am afraid you are ill - perhaps so ill that your letters have to be read to you. And so I must not make this a longer one. If you are ill, [may?] some one tell me please?

Very sincerely yours,

Alice Brown

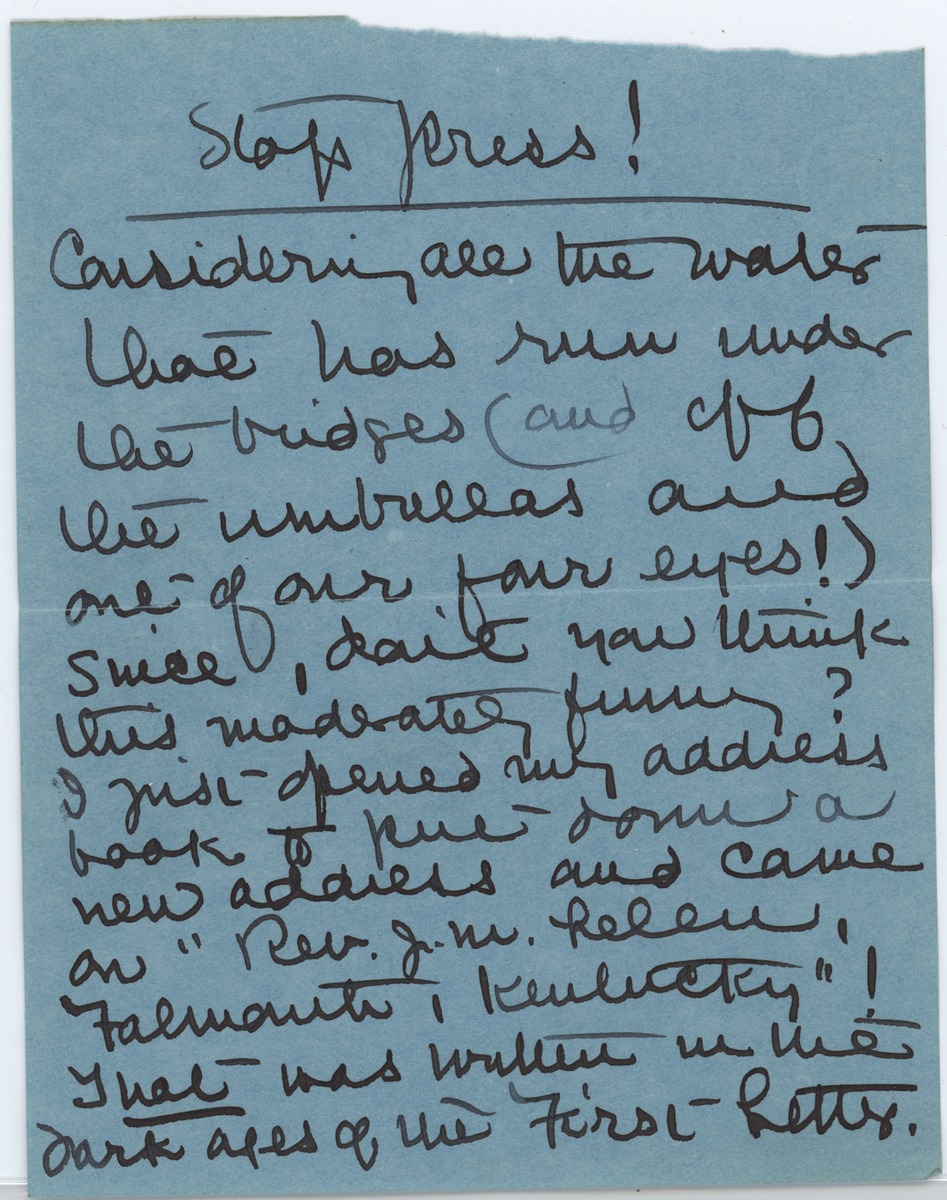

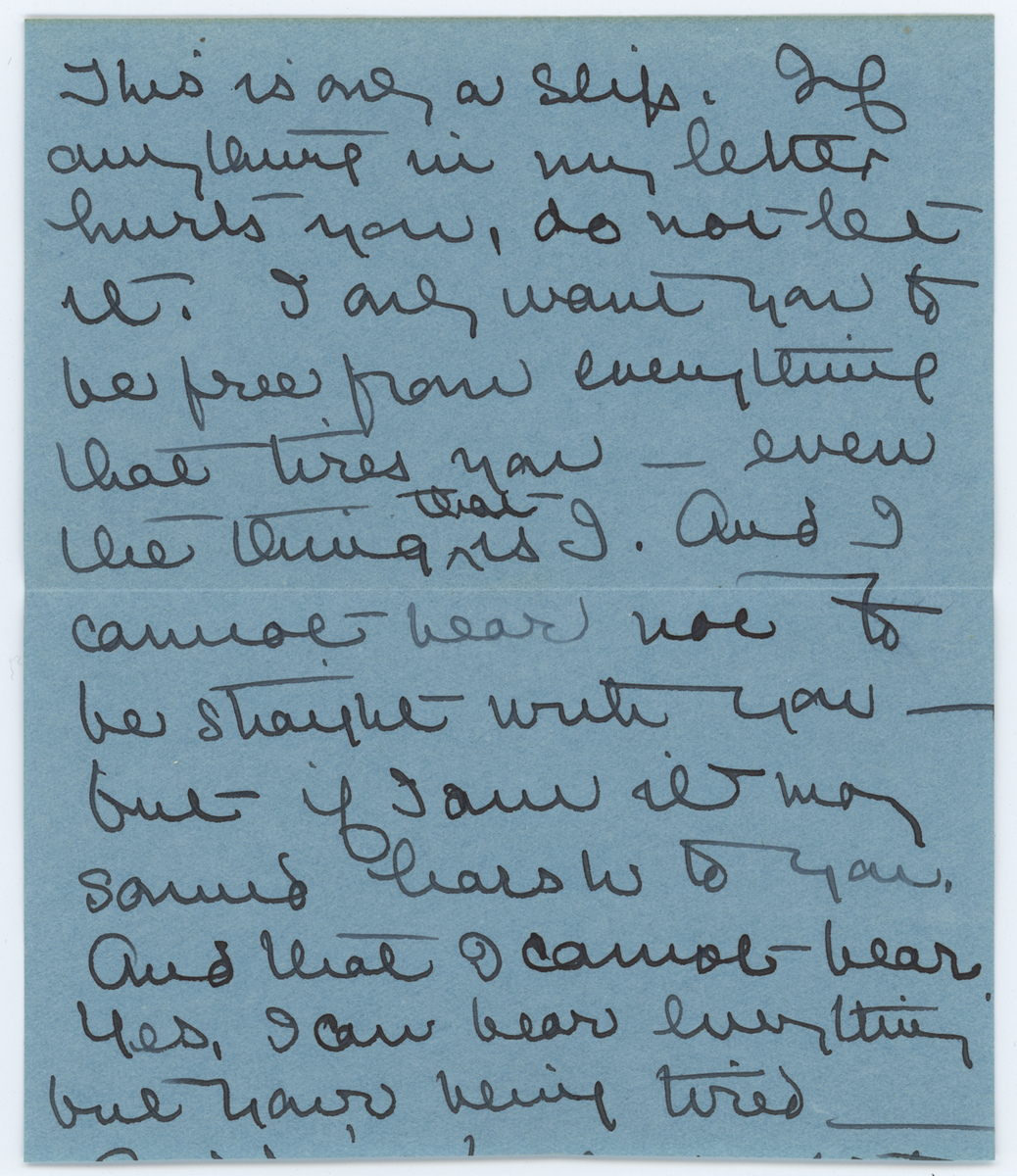

Letter 2

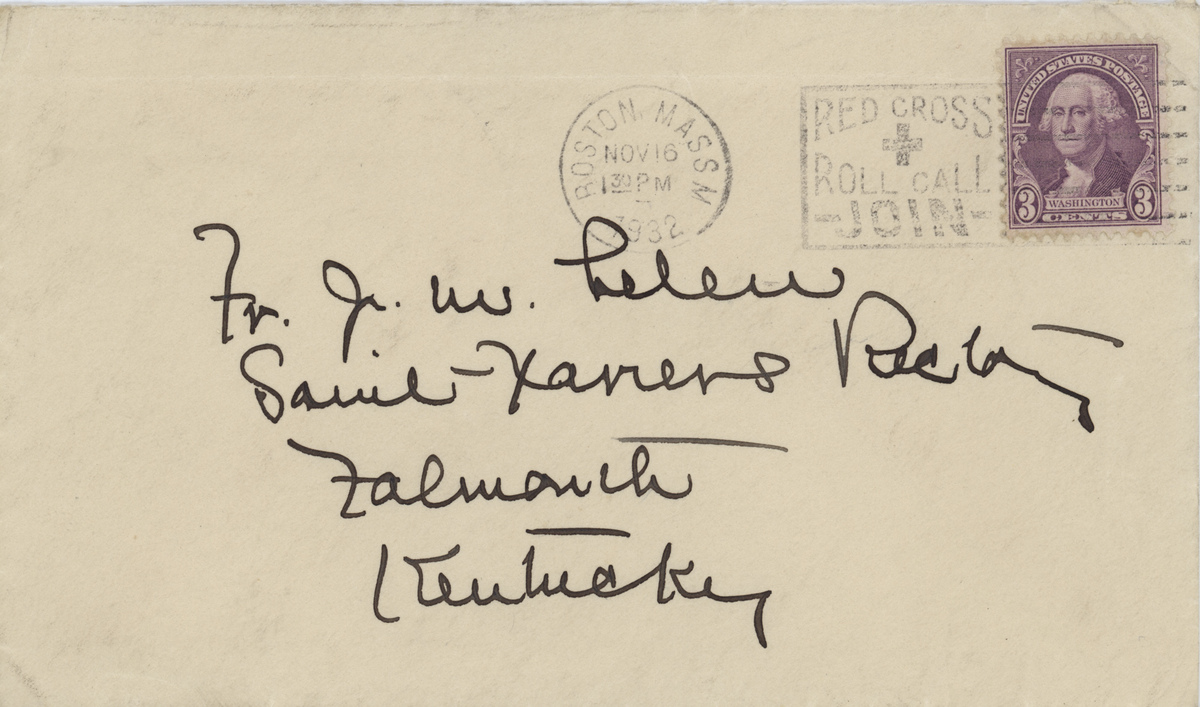

Envelope addressed to:

Fr. J.M. Lelen

Saint-Xavier's

Falmouth, Kentucky

{Boston, Mass.

May 28, 1932}

Stop Press! Considering all the water that has run under the bridges (and off the umbrellas and out of our fair eyes!) Smile, don't you think this moderately funny? I just opened my address book write down a new address and came on "Rev. J.M. Lelen, Falmouth, Kentucky"! That was written in the dark ages of the First Letters. This is only a slip. If anything in my letter hurts you, do not let it. I only want you to be free from every thing that tires you, even the thing that is I. And I cannot bear not to be staying with you but if I am it may sound harsh to you. And that I cannot bear. Yes, I can bear everything but your being tired. I don't remember having been approached for that Anthology - The Allyn + Bacon - but I always refer anthologists to MacMillian and they arrange it - for a fee. But if the authors wrote prefaces to their stuff and told [illegible] snaked eggs, I know I should have refused instantly. I now will mix myself up with that quack nostrum business. But - "Be patient when your child is exasperating!"

Letter 3

Assuming that the "Vicar of Christ" is divinely ordained, don't you mean the office and not the man? For to the reader it seems to mean the actual man - a man who could have nephritis of the form where the patient has false visions - and yet is innocent of heart - or is under some undiagnosed physical curse which jangles the action of the mind. And even if the man is officially "infallible" God will not for that reason perform on him a miracle of healing. God doesn't administer in that way. I should guess that you mean the Pope's over-lordship, being adopted as a necessity of the Church to guard against [illegible] and rash leadership. - must be absolute. Therefore an obedient Catholic will "love" it and obey.

Letter 4

How amazing the little paths of being are from God to man! Because God can't make us hear until we hear! And He patiently tries again. I see now that I have blinded you, drenched you, over-weighted you with my floods of letters. And you would never tell me so because you will not "hurt". And then you told me to use slips and the slips have done it. When I see one before me it looks up to me and says "Is it sane thing to say? Because I'm small and I can't bother with you if you merely want to write." So forgive me the past and trust me to amend the future. And believe I do not forget to pray God bless you, All my love.

Letter 5

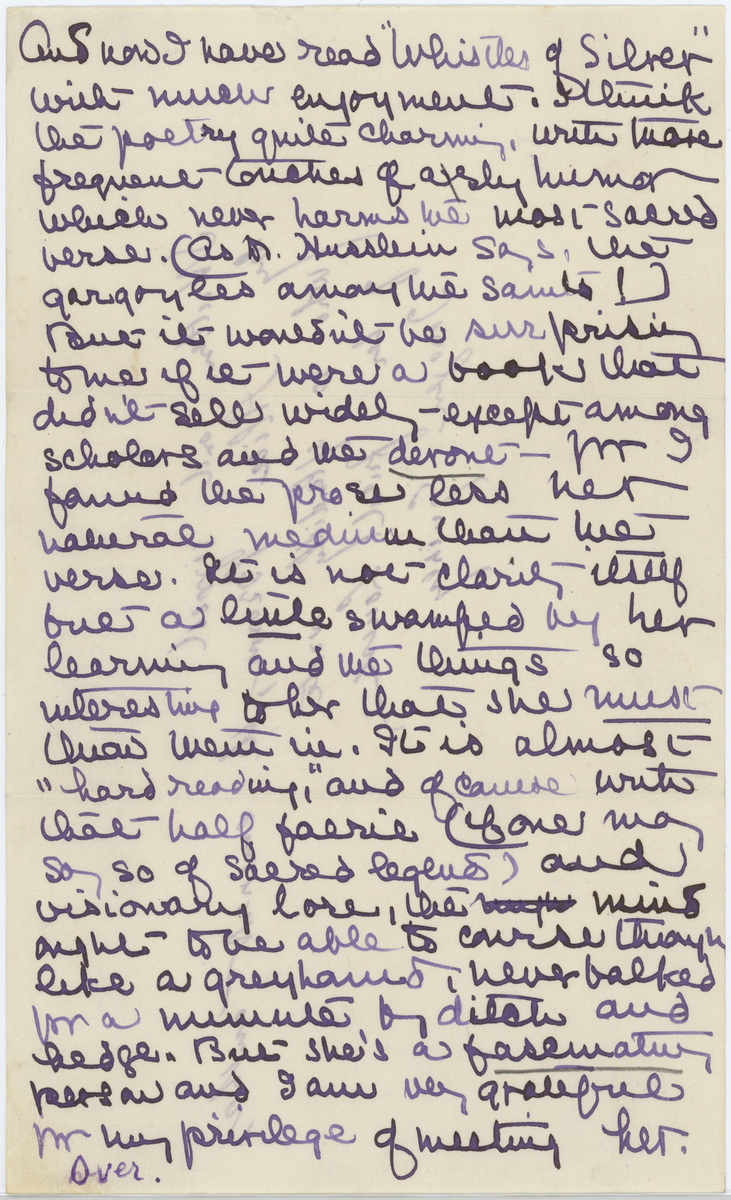

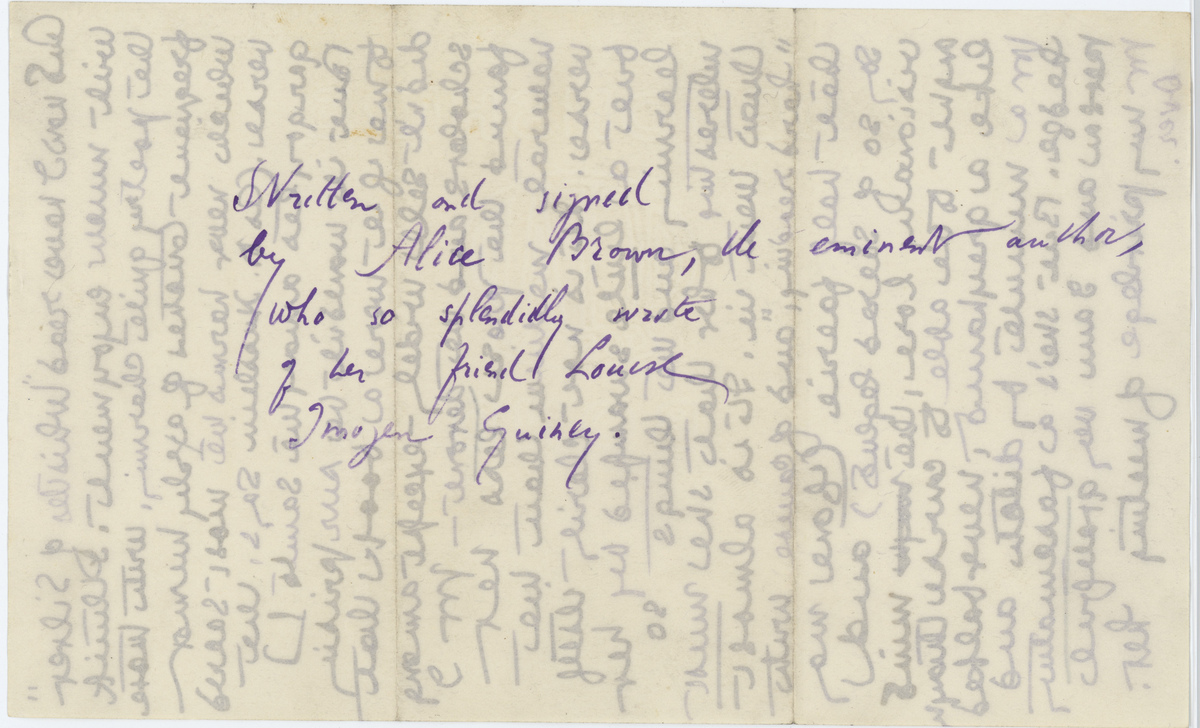

And now I have read "Whistles of Silver" with much enjoyment. I think the poetry quite charming, with those frequent touches of a sly humor which never harms the most sacred verse. (As [Dr.?] Husslein says, that gargoyles away the saints! But it wouldn't be surprising to me if it were a book that didn't sell widely except among scholars and the devout - [illegible] I found the prose less her natural medium than the verse. It is not clarity itself but a little swamped by her learning and the things so interesting to her that she must [illegible] them in. It is almost "hard reading", and of course with that half faerie (if one may say so of sacred legends) and visionary lore, the mind ought to be able to course through like a greyhound, never balked for a minute by ditch and hedge. But she's a fascinating person and I am very grateful for my privilege of meeting her. Over.

{Written and signed by Alice Brown, the eminent author, who so splendidly wrote of her friend Louise Imogen Guiney.}

Works Cited/Consulted

Lambert, Deborah G. "Alice Brown (5 December 1856-21 June 1948)." American Short- Story Writers, 1880-1910. Ed. Bobby Ellen Kimbel and William E. Grant. Vol. 78. Detroit: Gale, 1989. 21-31. Dictionary of Literary Biography Vol. 78. Dictionary of Literary Biography Complete Online. Web. 13 Apr. 2015.

Overton, Grant M. The Women Who Make Our Novels. New York: Moffat, Yard, 1918. Print.

Transcendental Elements in the Fiction of Alice Brown. Digital Repository @ Iowa State University, 1987. Internet resource.

Wagner-Martin, Linda, and Cathy N. Davidson. The Oxford Book of Women's Writing in the United States. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1995. Print.

Westbrook, Perry D. A Literary History of New England. Bethlehem: Lehigh UP, 1988. Print.