Joanna Baillie

Joanna Baillie was born in Bothwell, near Glasgow, Scotland on September 11, 1762. She grew up in rural Scotland with the close companionship of her sister Agnes and brother Matthew. She was raised by an intellectual family with strong connections to the universities at Glasgow and Edinburgh. Her mother, Dorothea Hunter Baillie was related to highly regarded physicians of the time and her father, Rev. James Baillie was, for a short time, a professor of Divinity at the University of Glasgow. Rev. James Baillie and the Scottish moral, philosophical tradition influenced Baillie's writing ("Scottish Women Poets"). When she was 10 years old, she was sent to Miss McDonald's boarding school in Glasgow where her talents for writing and theatre were realized (Clarke). Her first poem she wrote as a child was a satire on her father's servant but by the time she reached her teenage years, her style became more sophisticated and she started writing plays in verse. In 1778, at the age of 15 years old, her father passed away. His death, along with the little inheritance Dorothea Baillie received, sent her and Joanna to live with her brother, William Hunter, on his estate outside of Glasgow. A year later, Joanna started to compose ballads and songs. In 1783, Dr. William Hunter died leaving Matthew Baillie his house and museum collection in London. Joanna, Agnes and their mother moved to the house in London on Windmill Street, to maintain it for Matthew. In London, Joanna accessed the literary society through her aunt, Anne Hunter, who encouraged her to become more serious in her writing. While at Windmill Street, Joanna focused her writing abilities on drama. The great tragedienne Sarah Siddons acted in her play, De Monfort, which was one of a series of plays on the Passions. By 1799 Joanna had moved to Hampstead where she lived with her sister Agnes for the next 50 years; neither of them married. While in Hampstead, Joanna produced the majority of her work and befriended other well-known authors of the time such as Anna Letitia Barbauld, Maria Edgeworth, Walter Scott and William Wordsworth. Financially secure with the income she recieved from her writing, Joanna customarily gave 50% of her earnings to charity and engaged in many philanthropic activities (Clarke).

Joanna's writing consisted mostly of Romantic poems and plays. Her work spanned the entire Romantic period from 1790 when her first volume of Poems was published to 1851 when she published The Dramatic Poetical Works (Breen). Much of her work focuses on various human passions more so than on the characters who reveal those passions. The language she uses in her writing is simple yet forceful. In Judith Bailey Slagle's biography called, Joanna Baillie, A Literary Life, she describes Joanna's life as a writer as highly conflicted, "Her conflicts were many and complex: her passion for secular literature and religious doctrine, supporting women writers through her association with literary men, admiring Lord Byron's poetry while hating the man, remaining a close friend to many famous men but rejecting them as intimate partners, and seeking detachment from but remaining disappointed in her work" (Slagle). She initially published some of her poetry and plays anonymously and, as stated in her obituary, "contrary to all expectation, they were found to be the writings of a woman." She was established as one of the principal playwrights of her time, even more successful than her male peers (Laidlaw). Throughout her life she wrote 27 plays, songs and hymns, a religious tract, several theoretical prefaces, and over 100 poems. She also kept fervent correspondence with many people, especially those in the United States. Deeply disappointed with the lack of success of some of her plays, she used her connections to bring her plays to the United States, where they found great success in certain cities. In 1852, a year after The Dramatic and Poetical Works of Joanna Baillie was published, Joanna Baillie died in Hampstead. After her death, her work seldom found its way into English canon and the lack of success in her plays can be attributed to audiences' taste for melodramatic productions (Noe).

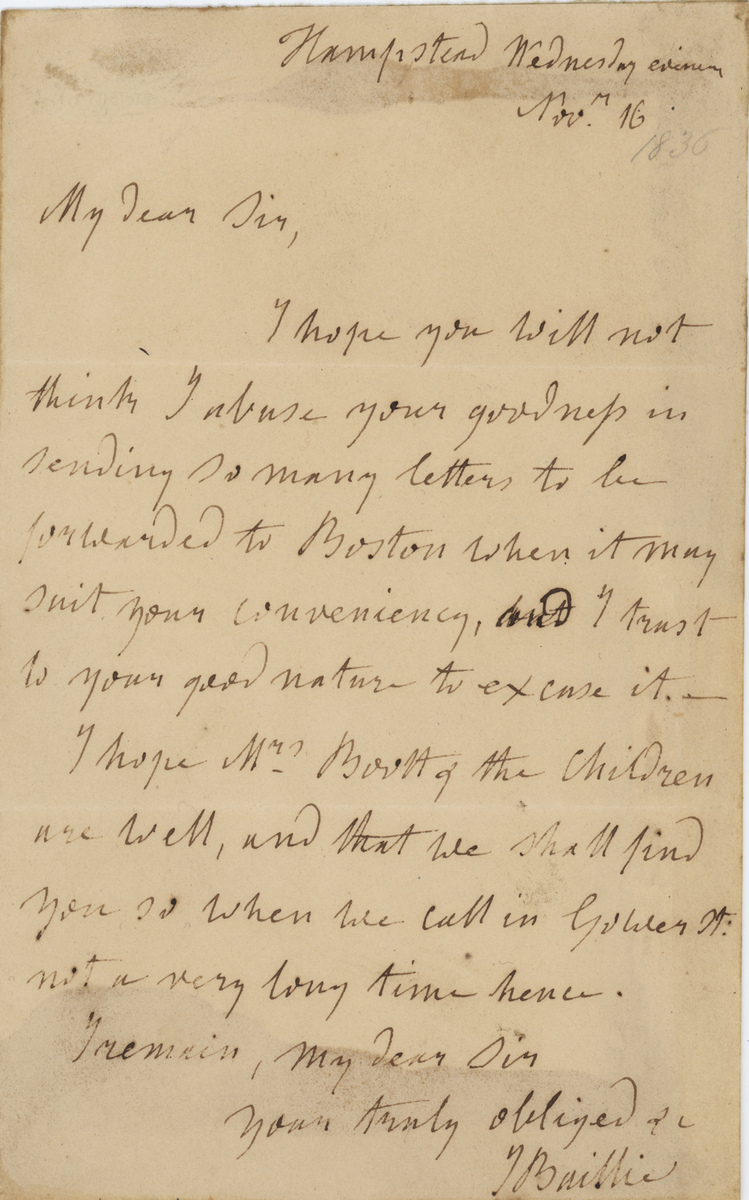

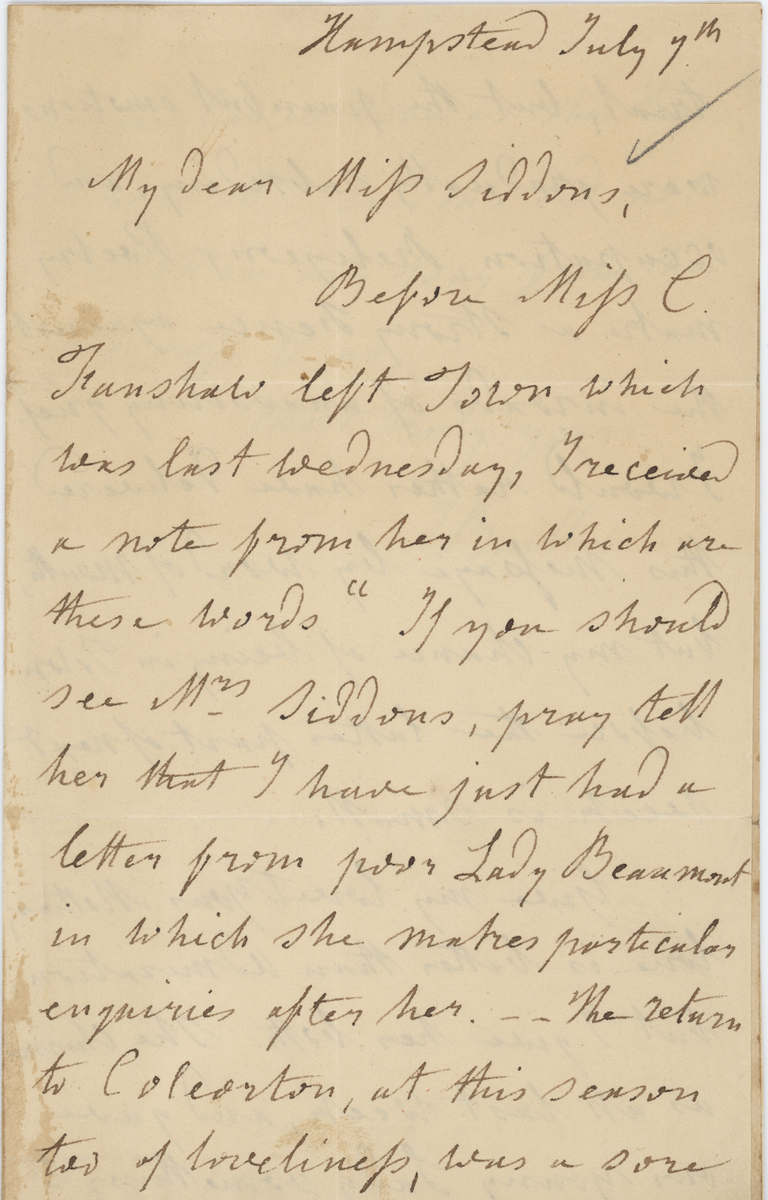

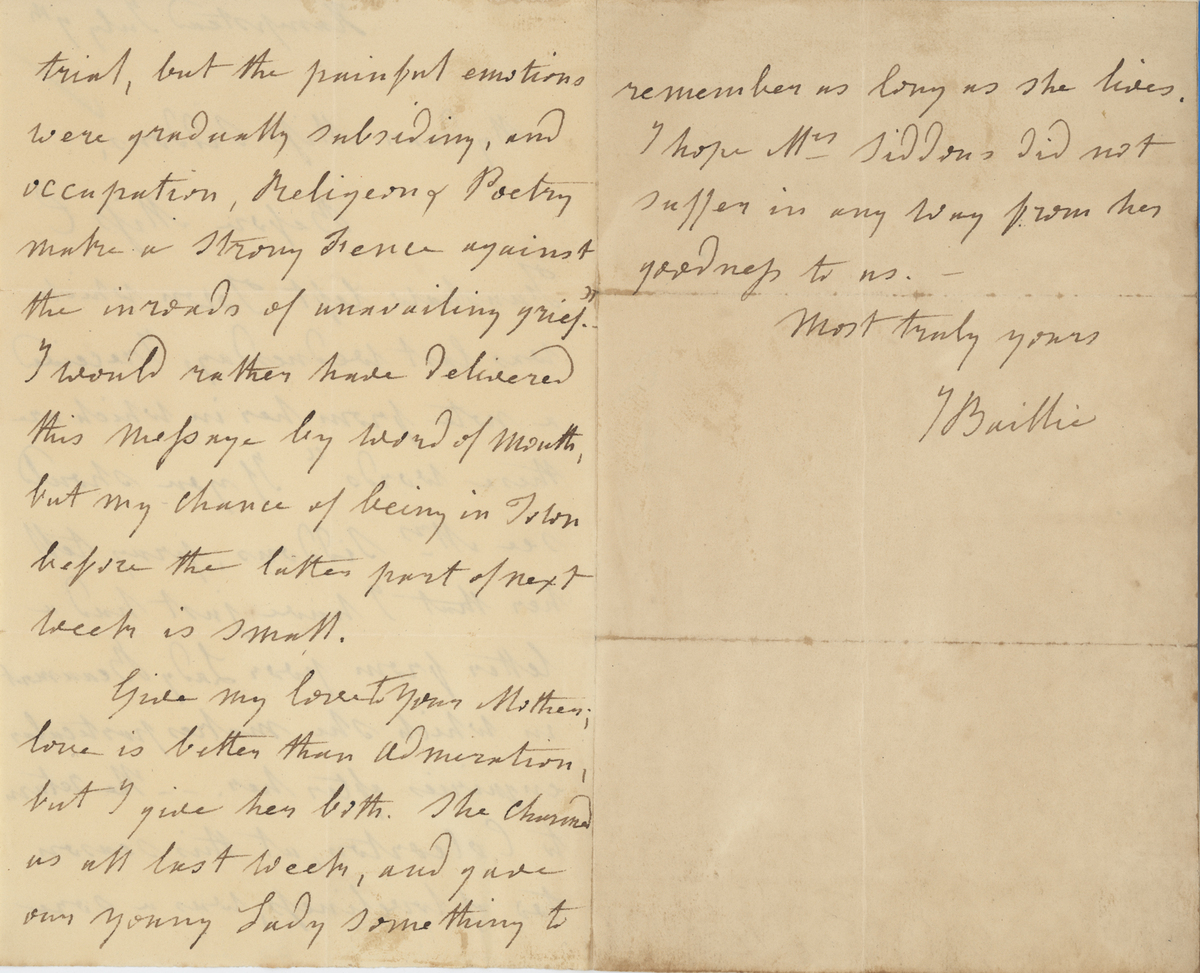

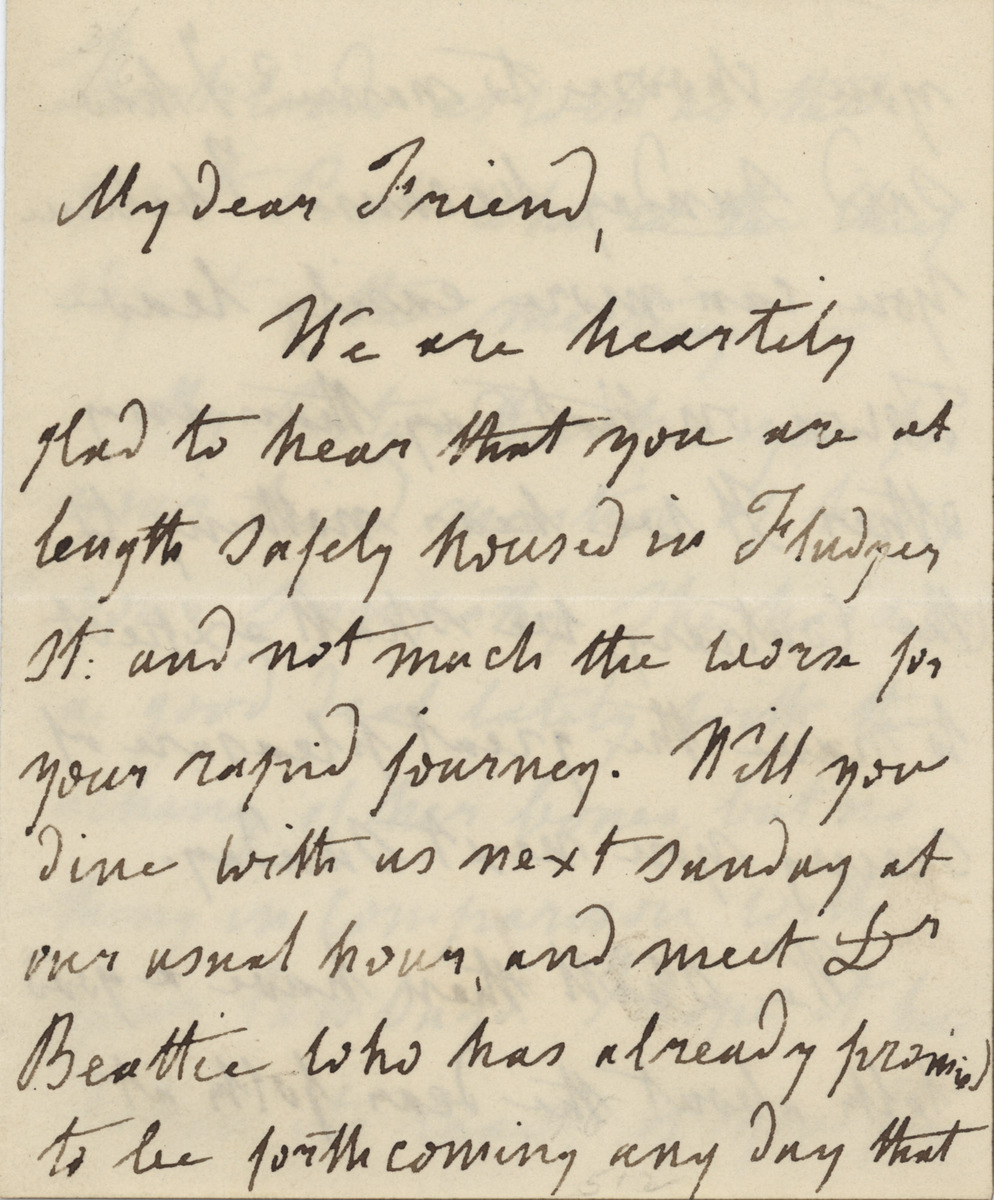

Baillie's earliest surviving letter dates from 1800 and more than one thousand letters, dating from 1800 to 1851, have been found in archives around the world (McLean). Many of them have been published, yet it is believed that many more have yet to be found. Her letters reveal deep insights into her literary and personal life. Correspondence with actress Sarah Siddons at times reveals an "uneven" relationship (McLean), but in letter 2 Joanna writes Cecilia Siddons, daughter of Sarah Siddons, showing Baillie's warmth towards the famous actress in later years. Many of her letters have a theme of persistent ambition tied closely with sharp disappointment (Noe). She writes them with a melancholic tone that reveals a sort of longing and self-pity (Noe). Letter 1, is a letter she wrote while in Hampstead to a man on Wednesday evening, November 16th, 1836. The letter is addressed "Dear Sir", but on the back of the letter, there is the name Mr. B[ooth?]. Many of her letters addressed "Dear Sir" are written to someone she is very familiar with. She asks him to forward on her correspondence to Boston, which she makes sound like a regular event. She also wishes his family well and discusses a future arrangement with them. As stated previously, Letter 2 was written from Hampstead to Mrs. Siddons, forwarding on a message from another friend telling her that someone is looking for her and discusses the occupations of "Religion and Poetry" when dealing with the universal emotion of grief. She discusses how charming Mrs. Siddons' mother is and thanks them for coming. In Letter 3, she writes to a friend who has recently been "housed" on Fludger St. She asks them to come dine with them to meet Beattie on Sunday because she believes that is best for everyone's schedules. She wants to discuss the "great Poet who is the chief object of the meeting". She also shows appreciation and thanks for her mention of her sister who has been suffering from physical ailments.

Letter 1

{Hampstead Wednesday evening, Nov. 16th, 1836}

My Dear Sir,

I hope you will not think I abuse your goodness in sending so many letters to be forwarded to Boston when it may suit your convenience, but I trust to your good nature to excuse it. --

I hope Mrs. B[illegible] and the children are well, and that we shall find you so when we call in G[ower?] St. not a very long time hence.

I remain, My dear sir,

Yours truly obliged,

J. Baillie

{Dr. Boo[th?]}

Letter 2

{Hampstead, July 7th}

My Dear Miss Siddons, Before Miss C. [Fr?]anshaw left town which was last Wednesday, I received a note from her in which are these words "If you should see Mrs. Siddons, pray tell her that I have just had a letter from poor Lady Beaumont in which she makes particular enquiries after her. -- The return to Coleorton, at this season too of loveline[ss?], was a sore trial but the painful emotions were gradually subsiding, and occupation, Religion and Poetry make a strong fence against the inroads of unavailing grief." I would rather have delivered this message by word of mouth, but my chance of being in town before the latter part of next week is small. Give my love to your mother; love is better than admiration, but I give her both. She charmed us all last week, and gave our young Lady something to remember as long as she lives. I hope Mrs. Siddons did not suffer in any way from her goodness to us.

Most Truly Yours,

J. Baillie

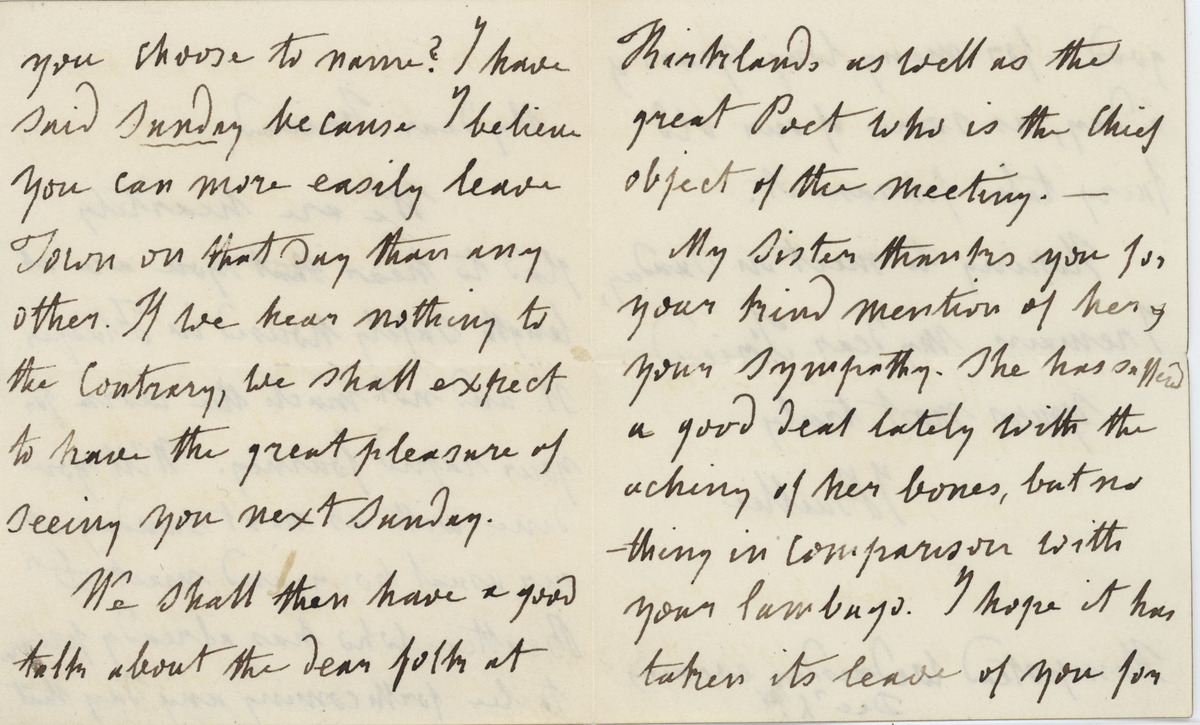

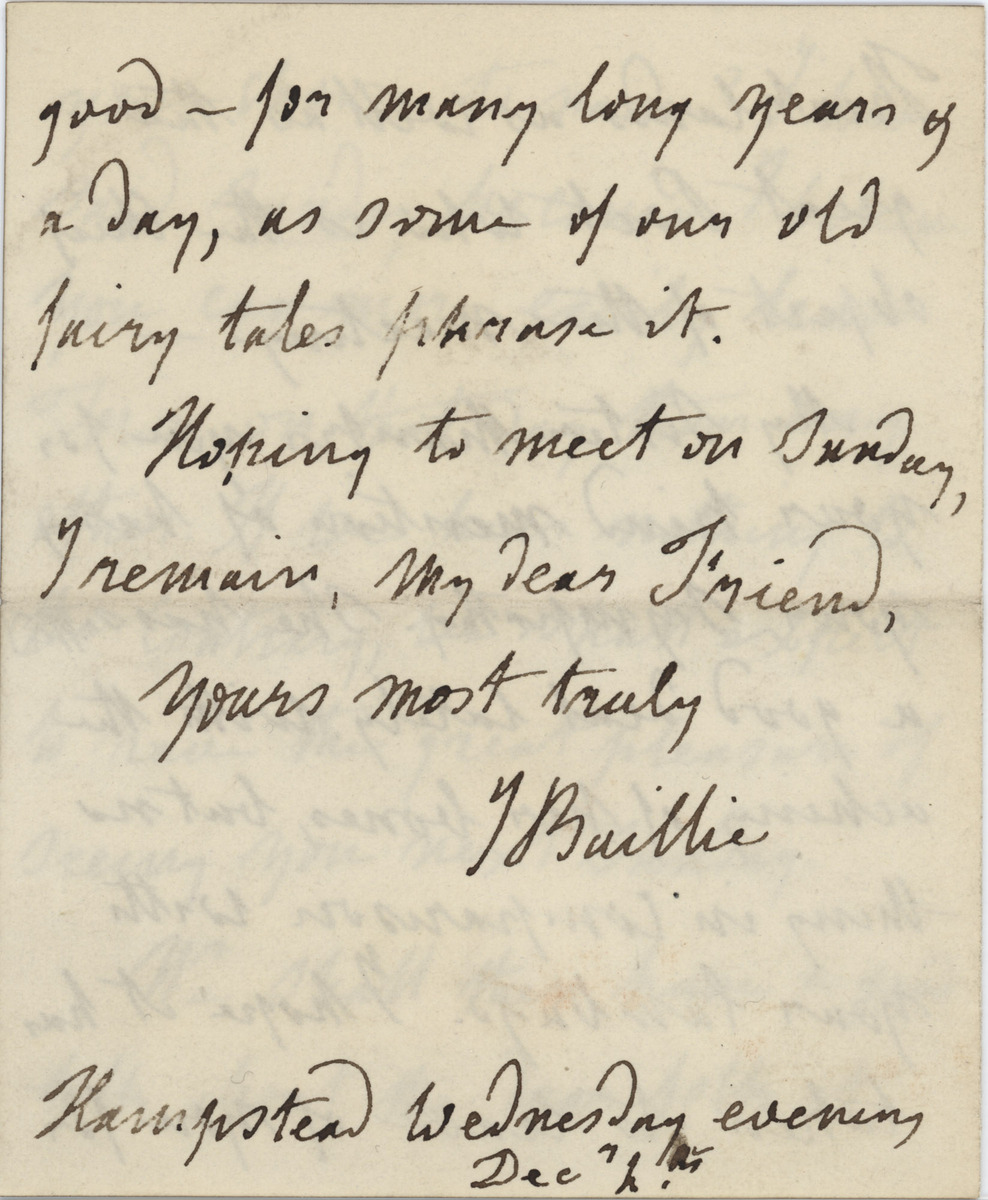

Letter 3

My Dear Friend,

We are heartily glad to hear that you are at length safely housed in Fludger, St.: and not much the worse for your rapid journey. Will you dine with us next Sunday at our usual hour, and meet Beattie who has already promised to be forth coming any day that you choose to name? I have said Sunday because I believe you can more easily leave town on that day than any other. If we hear nothing to the contrary, we shall expect to have the great pleasure of seeing you next Sunday. We shall then have a good talk about the dear folks at [Kirklands?] as well as the great Poet who is the chief object of the meeting. --My sister thanks you for your kind mention of her and your sympathy. She has suffered a good deal lately with the aching of her bones, but nothing in comparison with your lumbago. I hope it has taken its leave of you for good - for many long years of a day, as some of our old fairy tales phrase it.

Hoping to meet on Sunday, I remain, my dear friend,

Yours most truly,

J. Baillie

{Hampstead Wednesday evening Dec 2nd}

Works Cited/Consulted

Baillie, Joanna, and Jennifer Breen. The Selected Poems of Joanna Baillie, 1762-1851. Manchester: New York, 1999. Print.

Baillie, Joanna, and Thomas McLean. Further Letters of Joanna Baillie. Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson UP, 2010. Print.

"Joanna Baillie." Poetry Foundation. Poetry Foundation, n.d. Web. 10 Apr. 2015.

Noe, Nancy. "Joanna Baillie (11 September 1762-23 February 1851)." Nineteenth- Century British Dramatists. Ed. Angela Courtney. Vol. 344. Detroit: Gale, 2009. 9-17. Dictionary of Literary Biography Vol. 344. Dictionary of Literary Biography Complete Online. Web. 13 Apr. 2015.

Slagle, Judith Bailey. Joanna Baillie, a Literary Life. Madison, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson UP, 2002. Print.

University of Victoria's English 471 Class. "Scottish Women Poets." Scottish Women Poets. N.p., n.d. Web. 10 Apr. 2015.

Clarke, Norma. “Baillie, Joanna (1762–1851).” Norma Clarke. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Ed. H. C. G. Matthew and Brian Harrison. Oxford: OUP, 2004. Online ed. Ed. Lawrence Goldman. May 2013. 10 Apr. 2015