Sarah Orne Jewett

Sarah Orne Jewett was an American novelist, short story writer and poet known as a great practitioner of American literary regionalism for her local color works. She was born as the second of three daughters on September 3rd, 1849 in South Berwick Maine to Caroline F. Perry and Dr. Theodore H. Jewett. She grew up in a literary home environment with extended family that encouraged her habit of reading many diverse writers. Her paternal grandfather was a successful retired sea captain and her maternal grandfather was a physician, leaving the family in comfortable financial circumstances. Her formal education was inconsistent because she suffered from rheumatism for which her physician father prescribed time outdoors. With the immense freedom that her father gave her, she frequently explored the outdoors. She also accompanied her father on medical rounds through rural and small-town Maine that provided her with material for her writing (Lauter). However, she did attend and graduate from Berwick Academy from 1861 to 1865. Three years later, at the age of 19, she published the short story, "Jenny Garrow's Lovers" in The Flag of Our Union under the pseudonym A.C. Eliot. She eventually released her real name and regretted when her family found out because she said it, "no longer belonged all to me." She wrote regularly for the Atlantic Monthly, The Independent, and St. Nicholas. After she went public in 1873, she sought out professional advice for her writing from editor and author, William Dean Howells who told her to write longer stories. Jewett decided she preferred to write "the sketchy kind" of stories as long as editors would accept them and people would read them. She frequently wrote to her friend Rose Lamb emphasizing the importance of "one's own method" instead of trying to meet the expectations of editors (Kisthardt).

With her own insistence on pushing the boundaries and not conforming, Jewett used modernist techniques for developing her characters and in her use of psychological reality over linear plot. Over time, her stories got shorter and shorter, due to her heavy focus on detail, and characterization that revealed insights into the lives' of her characters over linear plot. She gained inspiration for her works from "flash" observations of people. These "flashes" of inspiration came to her anywhere and they all "bewitched her" (Kisthardt). In her letters she discusses these flashes and a "season of writing" that reveal the impulsive nature of her writing (Kisthardt). Her distinct creative process shows up as a theme in her works. She liked to claim that in creating her works she had a vantage point that was in between "high" and "low" literature because her stories were inspired by actual events and people (Kisthardt). In many of Jewett's stories, there may appear to be a lack of plot but instead she uses a depth of characterization that reveals insights on the creativity and emotions of her characters.

By 1873, she could not financially support herself from her writing but thought of it as her work and vowed to remain true to her unique style despite editors' objections. Other famous authors that had an impact on Jewett and her writing were Harriet Beecher Stowe, William Dean Howells, Gustave Flaubert as well as Rose Terry Cooke, Celia Thaxter, Mary E. Wilkins Freeman, Alice Brown and Elizabeth Stuart Phelps. Her local color fiction focused on Maine and had a particularly more positive and light-hearted mood than most other local color fiction from New England at the time. However, she also was sure to reveal the harsh realities and injustices of village life in New England in her stories. Some common themes that she focused on were of gender and its' limiting possibilities for realizing one's potential, and one's connection with community (Kisthardt). She also was sure to never take a simplistic view of any of her characters and this helped her to delve into "the possibilities of rural life" (Kisthardt). In many stories, she focuses on the transforming power of female friendships. In one of her short stories, "A White Heron", she reconstructed the typical female bildungsroman that usually ended in marriage or in some way conforming to patriarchal cultural modes (Kisthardt). She also frequently uses nature and spiritualism both as themes and in the structure of her stories. Jewett lived her life as a journey of self-discovery and spiritual growth and often connected this with impulsive physical activity (Kisthardt). She also follows the Transcendentalist tradition and contemplates connection with nature, influence of the environment on character and the importance of heredity (Kisthardt).

By 1881, Jewett had established a network of friends with whom she regularly corresponded. She then traveled to Europe with her late publisher, James Fields' widow, Anne Fields for the next 18 years. After they returned, they spent summers in Manchester, Massachusetts and winters at Fields' home in Boston. Together, they wrote, read and entertained a wide array of literary people such as James Russell Lowell, John Greenleaf Whittier, Henry James and Marie Thérèse Blanc-Bentzon. Jewett and Fields' living situation was dubbed a "Boston marriage" and many others described their relationship as "inseparable" (Kisthardt). Henry James even called Jewett, Fields' adopted daughter. However, Jewett also openly wrote about same-sex relationships and her emotional longings for women in her diaries and letters (Kisthardt). During Jewett's summers in Manchester she would stay with her mother and sisters Mary and Caroline. In 1891 Jewett's mother died and a succession of other deaths of family members and friends quickly followed. These painful losses pushed Jewett further into her writing and during this time she completed the book she is best known for, The Country of Pointed Firs. The book explores women realizing their true potential by being true to themselves. After, she received high praise form Willa Cather and other well-known authors that solidified her position in American literature (Kisthardt). Jewett received an honorary Litt. D. degree from Bowdoin College in 1901. On her 53rd birthday, she was thrown from a carriage and sustained injuries from which she never fully recovered. In 1909 she suffered from a stroke that left her paralyzed until she passed away after a second stroke on June 24th. In 1910, Jewett's friends established the Sarah O. Jewett Scholarship Fund at Simmons College in memory of her.

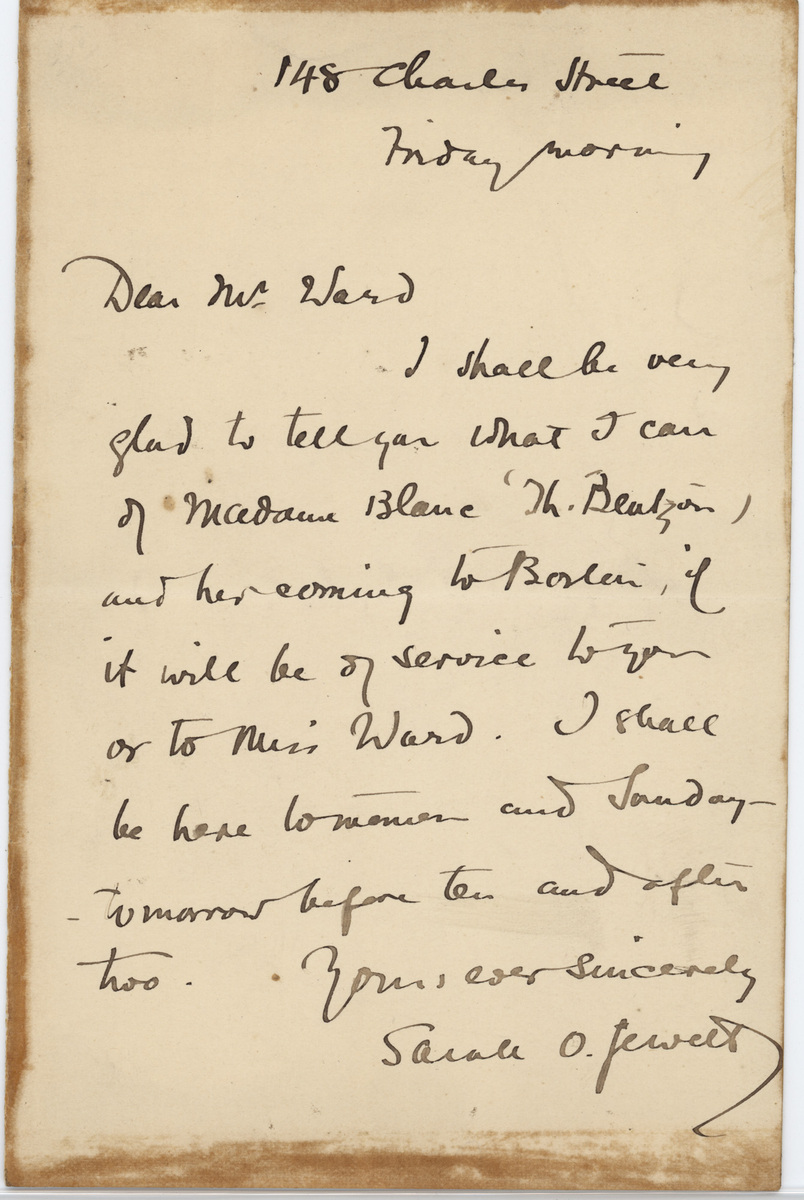

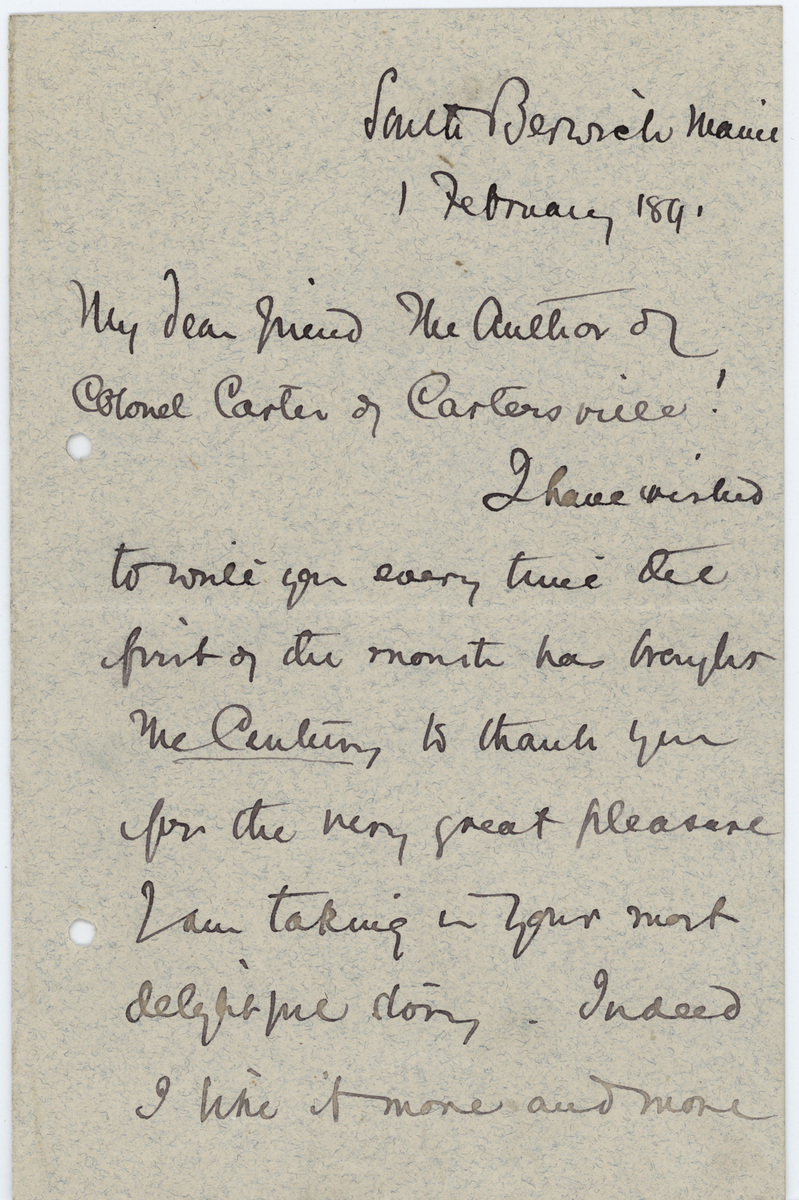

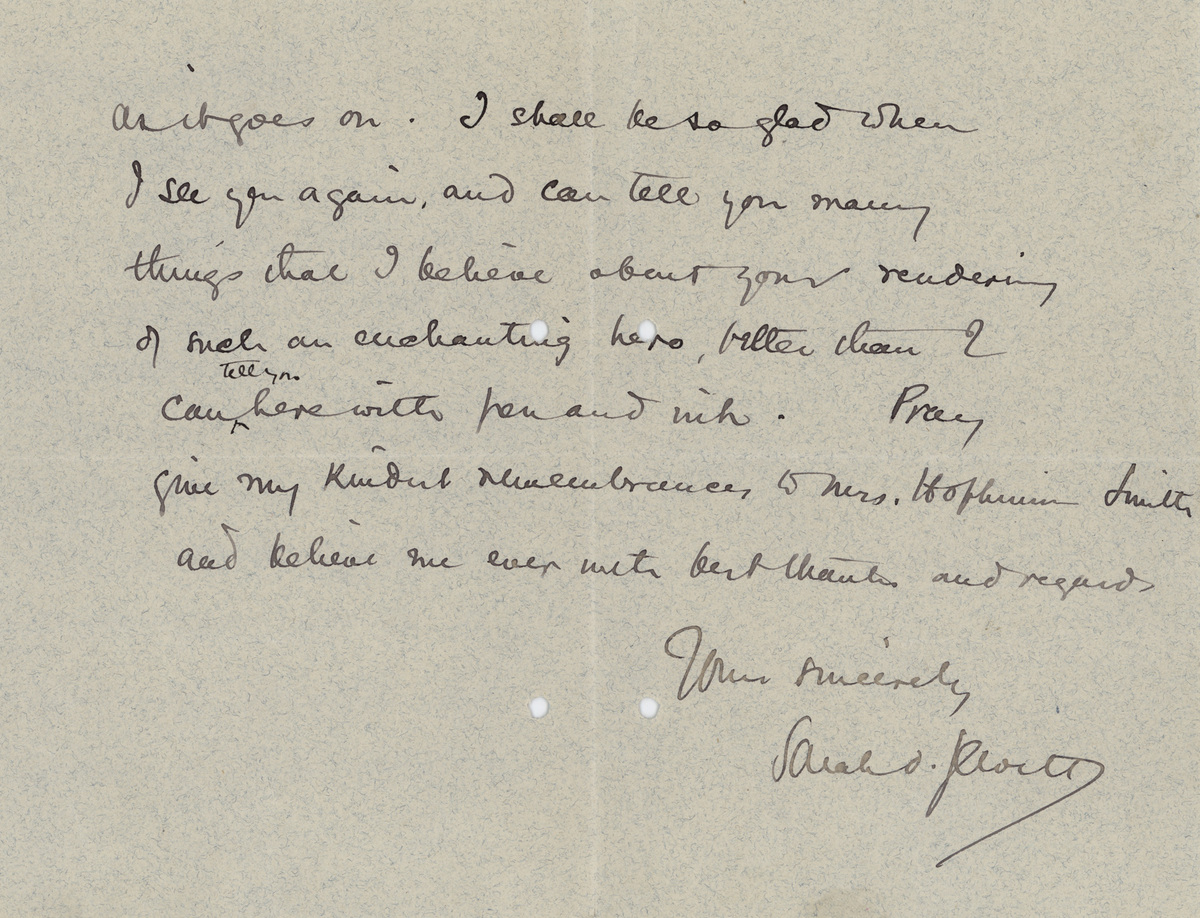

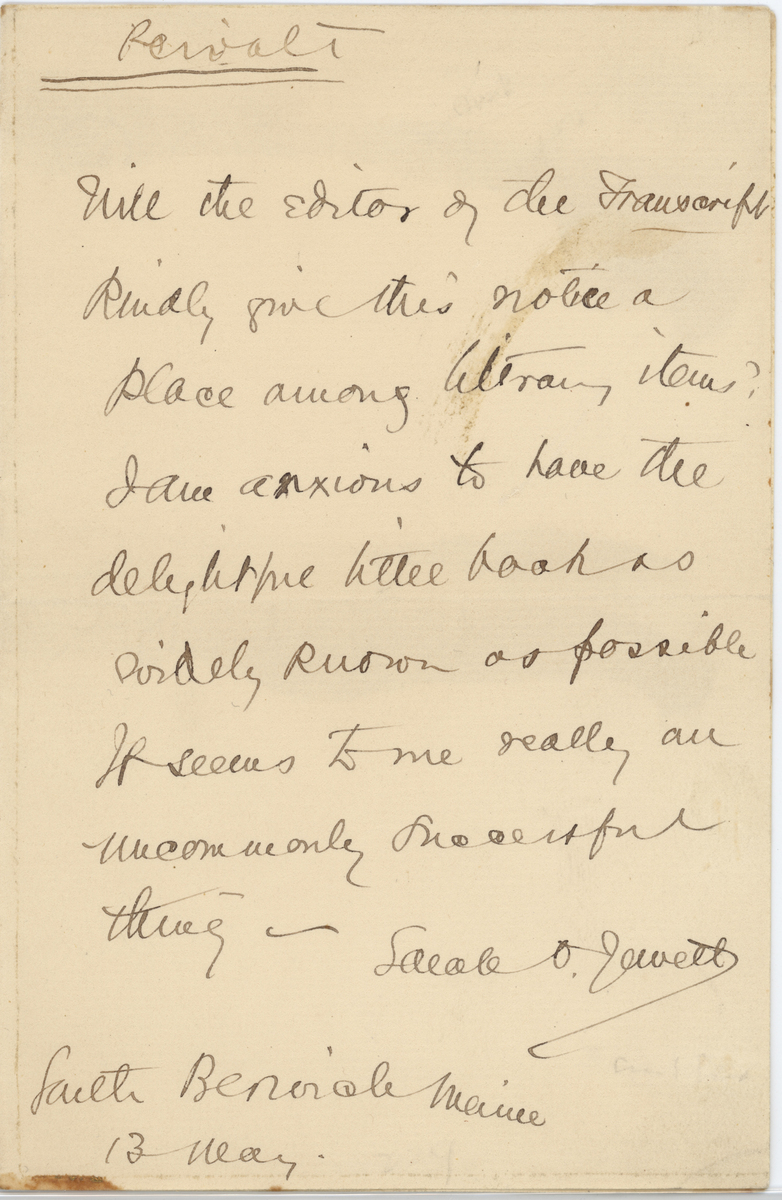

Sarah O. Jewett is known for her expansive correspondence with friends and acquaintances that discussed her life as a writer and gave insights into her relationships with others. In Letter 1, Jewett writes to Mr. Ward discussing Madame Blanc. She writes from Anne Fields' home at 148 Charles Street in Boston. She plans to meet up with Mr. Ward to discuss Madame Blanc and her imminent arrival into Boston. In Letter 2, she writes to the author of Colonel Carter of Cartersville (1891), Francis Hopkinson Smith. Smith was an American author, artist and engineer that famously built the foundation for the Statue of Liberty. She gives Smith high praise for his story and looks forward to a future meeting so she can give him commendation above that which "pen and ink" can give. Jewett's own focus on characterization and the creation of complex characters, gives rise to her particular comment about Smith's, "rendering of such an enchanting hero". She mentions Smith's wife, and sends thanks and regards. Letter 3, although short, gives a glimpse into Jewett's work as a writer and an esteemed member of literary society. While unclear the type of work that she wishes to promote, she clearly encouraged and supported other talented authors of her time.

Letter 1

{148 Charles Street, Friday Morning}

Dear Mr. Ward,

I shall be very glad to tell you what I can of Madame Blanc [illegible] and her coming to Boston if it will be of service to you or to Miss Ward. I shall be here tomorrow and Sunday - tomorrow before ten and after two.

Yours ever sincerely,

Sarah O. Jewett

Letter 2

{South Berwick Maine, February '89}

My dear friend the Author of Colonel Carter of Cartersville!

I have wished to write you every time the fruit of the month has brought Mc[illegible] to thank you for the great pleasure I am taking in your most delightful story. Indeed I like it more and more as it goes on. I shall be so glad when I see you again, and can tell you many things that I believe about your rendering of such an enchanting hero, better than I can tell you here with pen and ink. Pray give my kindest remembrance to Mrs. Hof[illegible] Smith and believe me ever with best thanks and regards,

Yours Sincerely,

Sarah O. Jewett

Letter 3

Will the editor of the Transcript kindly give this notice a place among literary items? I am anxious to have the delightful little book as widely known as possible. It seems to me really an uncommonly successful thing ~

Sarah O. Jewett

{South Berwick Maine, 13 [May?]}

Works Cited/Consulted

Ammons, Elizabeth. "Sarah Orne Jewett." Heath Anthology of American Literature Sarah Orne Jewett - Author Page. The Heath Anthology of American Literature, n.d. Web. 21 Apr. 2015.

Heller, Terry. "Sarah Orne Jewett Text Project." Sarah Orne Jewett Text Project. Coe College Department of English, n.d. Web. 21 Apr. 2015.

Kisthardt, Melanie. "Sarah Orne Jewett (3 September 1849-24 June 1909)." American Women Prose Writers, 1870-1920. Ed. Sharon M. Harris, Heidi L. M. Jacobs, and Jennifer Putzi. Vol. 221. Detroit: Gale, 2000. 219-229. Dictionary of Literary Biography Vol. 221. Dictionary of Literary Biography Complete Online. Web. 21 Apr. 2015.

"Sarah Orne Jewett". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 2015. Web. 21 Apr. 2015

"Sarah Orne Jewett: a Writer's Life." Choice Reviews Online. 31.1 (1993): 31-162. Print