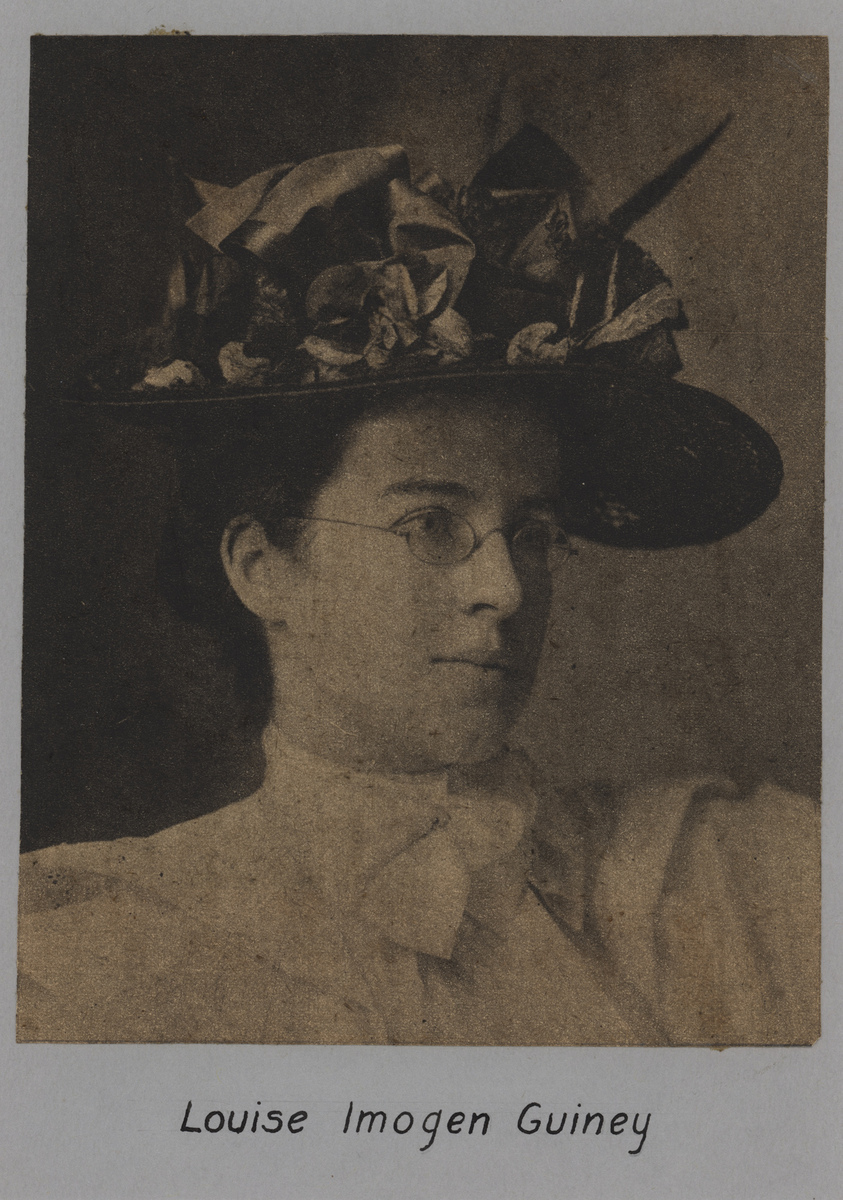

Louise Imogen Guiney

Louise Imogen Guiney was poet known for her lyrical, 17th Century style that reflected her Catholic faith, devotion to moral righteousness, and ideal of heroic chivalry. She was born on January 7, 1861, at Roxbury in Boston's South End to an Irish immigrant father, Patrick Robert Guiney who was a Brigadier-General decorated for heroism in the Civil War. Due to injuries he sustained in the war, he was an invalid in his home in 1862 at the age of 28. These events hugely shaped Guiney's perspective and the themes that would appear in her later works. In 1877, while Imogen was studying at Elmhurst Academy in Providence, RI, her father passed away from his wounds. She then graduated from Elmhurst in 1879 and for the next 21 years of her life, lived with her mother and aunt in Auburndale, Massachusetts and Boston. In the 1880's the publication of her essays and poetry in newspapers and magazines along with her Elmhurst education helped to elevate her amongst Boston's literary elite. John Boyle O'Reilly, editor at the Boston Pilot, was her first publisher and got her connected with Boston literati such as Francis Parkman, Brooks Adams, George Parsons Lathrop and James and Annie Fields. After her the success of her first book, the City of Boston commissioned her to write a memorial ode to General Grant. Later, Harper's and The Atlantic Monthly published her poetry and prose. Her second book of verse published was called The White Sail and Other Poems in 1887 and received criticism but also revealed maturation in her talents. Critics of her work often said that her writing was too dense. She continued to develop this compressed style even though she knew its drawbacks (Leggott). She accepted a teaching position at Smith College but was later told that her qualifications were inadequate. Out of disappointment and desperation for money, she published Brownies and Bogles in 1888, which was a collection of fairy tale stories. From 1889-1891 Guiney and her mother made a journey to England, with side visits to Ireland and France, which would later prove pivotal in Guiney's writing. During her visit she met many well-known literary figures and antiquarians while making money from the English letters she contracted to write for the Boston Post. Despite this, after her return home in 1891, she fell on economic hardship causing her and Alice Brown to edit A Summer in England, A Hand-Book for the Use of American Women (1891), among many other famous works. At this point in her life, she prepared what would be her most important poetry collection, A Roadside Harp (1893) that was a compilation of poems written because of her travels and reveals her pleasure in a land that was still incredibly resonant with the sources of her own poetry (Leggott). Despite her fame and extensive production of works, she could still not make ends meet and was employed as Auburndale's postmistress. The work included long hours, which hindered her writing time and impaired her creativity. Fortunately, she was able to gain this time and creativity back when her and Alice Brown escaped to England and Wales for a walking tour in the Summer of 1895. The emotional and creative boost that the trip gave her allowed her to continue writing prose such as A Little English Gallery, where she wrote essays on writers such as Henry Vaughan, George Farquhar and William Hazlitt. In 1895 she also published a piece of fiction called Lovers' Saint Ruth's and Three Other Tales. The best prose works of the late 1890s that she produced was Patrins (1897) and was one of only two of her books to go into a second printing. Despite such output, she still was not making enough income and in 1899 reluctantly became a cataloguer at the Boston Public Library.

She had a constant longing for England, the land that inspired her works, and in a letter to Dora Sigerson in 1899 wrote, "Nevertheless, I have my snug dream of a long life, say in Red Lion Square...where I shall always have a raven to bring muffins for the family, (and celery, and clothes, and pin-money,) and where I shall have nothing on earth to do but dig in the seventeenth century, and edit and edit, and live in the odour of the folios." She had the opportunity to return to England with her aunt in 1901 and instead of continuing her creative work, she energetically dove into writing magazine essays, criticism and editing. While at Oxford, she produced an edition of two short prose works by Vaughan, wrote the biography of Robert Emmet, an 18th century Irish nationalist and a history of the Elizabethan martyr Edmund Campion (Leggott). In her literary studies, she brought mostly unknown authors and elevated them to be serious subjects of study by the academic world ("Louise Imogen Guiney", Poetry Foundation). During this time, she failed to establish herself as a poet in England and continued to have significant financial troubles. In 1902, her aunt died after a battle with a long illness. Her mother suffered a similar fate and died eight years later. After her mother's death, Guiney's own health started to deteriorate and she often had to put aside her largest academic work at the time called Recusant Poets (1938), where she edited a selection of Lionel Johnson's poetry and collaborated on a volume of his prose works (Leggott). She died at the age of 59 on November 2, 1920 in Chipping Campden, England of arteriosclerosis. Most criticism on Guiney focuses on her use of archaic poetic structures and themes as well as her subject matter, which was largely derived from classical legends, tales of medieval gallantry and from the natural world ("Louise Imogen Guiney", Poetry Foundation). She often used strong rhythm and imagery to portray heroism and moral strength. Recognition for her work never reached its' full height and began to fade because of her inability to adapt to the modernist mode. However, her mastery of the conventions of pre-modernist poetry is unparalleled. In The North American Review, Alice Brown gives Guiney the highest praise, "Poet first, poet in feeling always, even after the rude circumstances of life had closed her singing lips, she was an undaunted craftsman at prose."

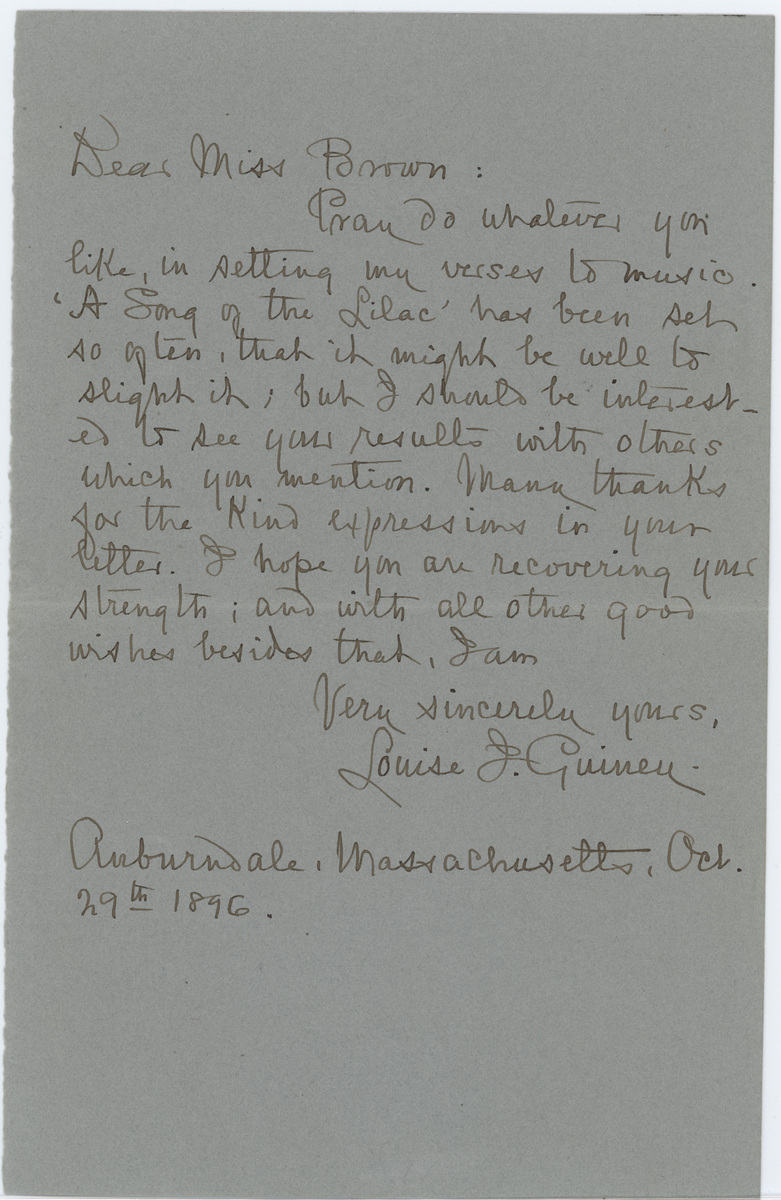

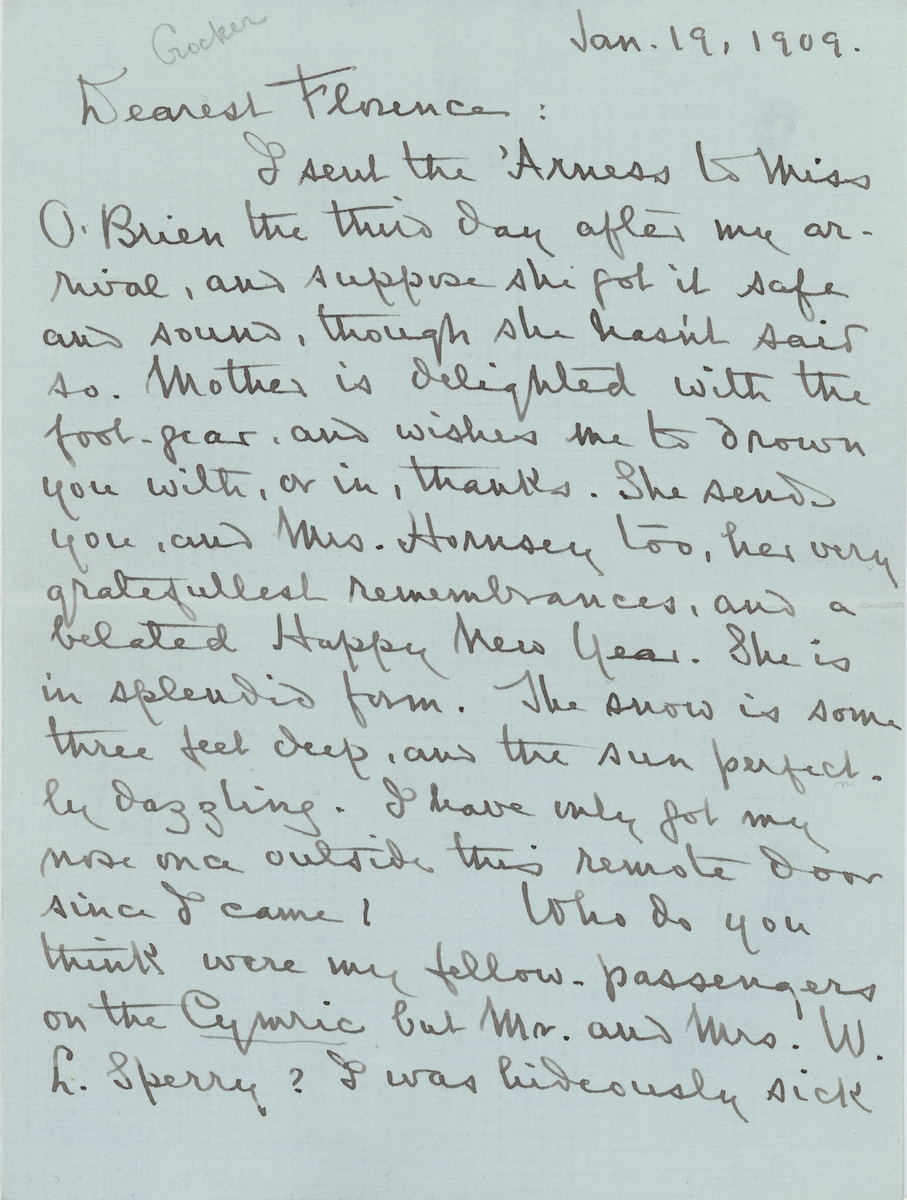

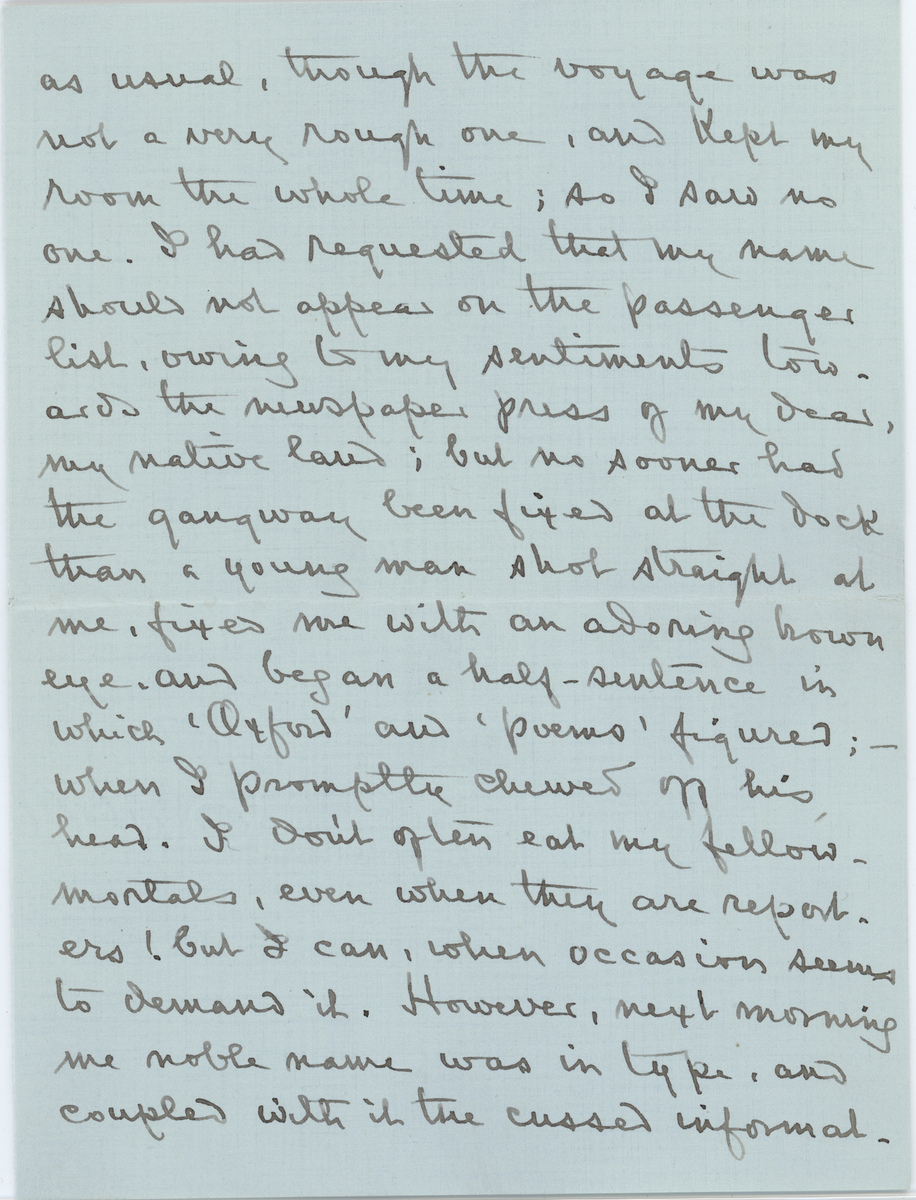

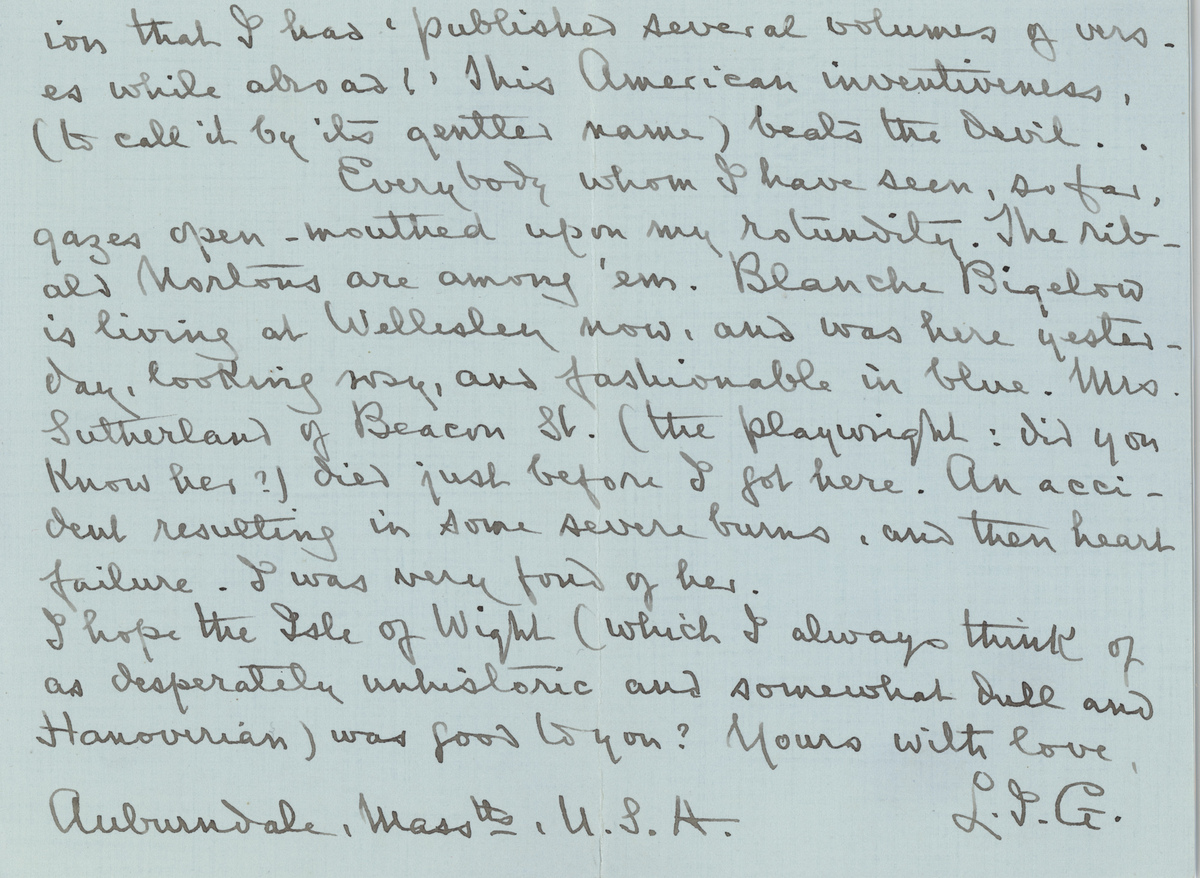

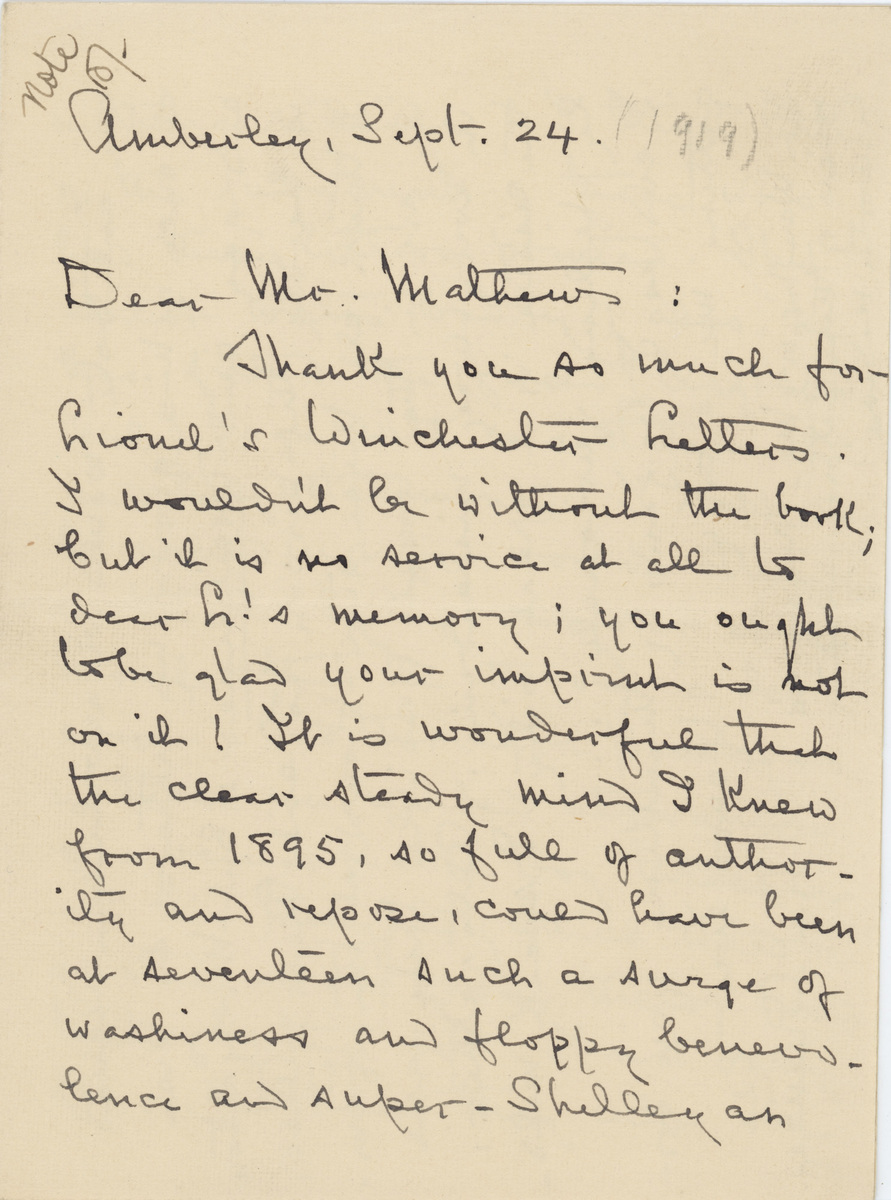

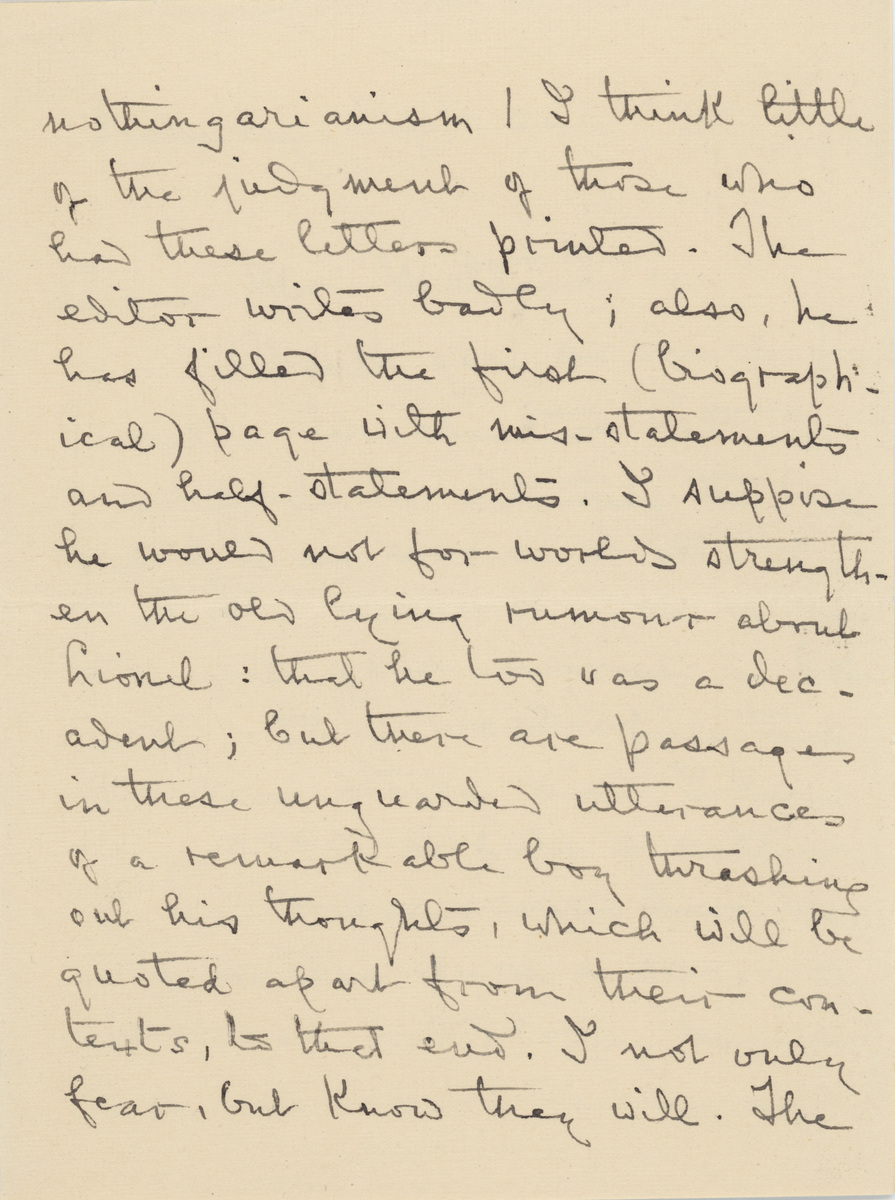

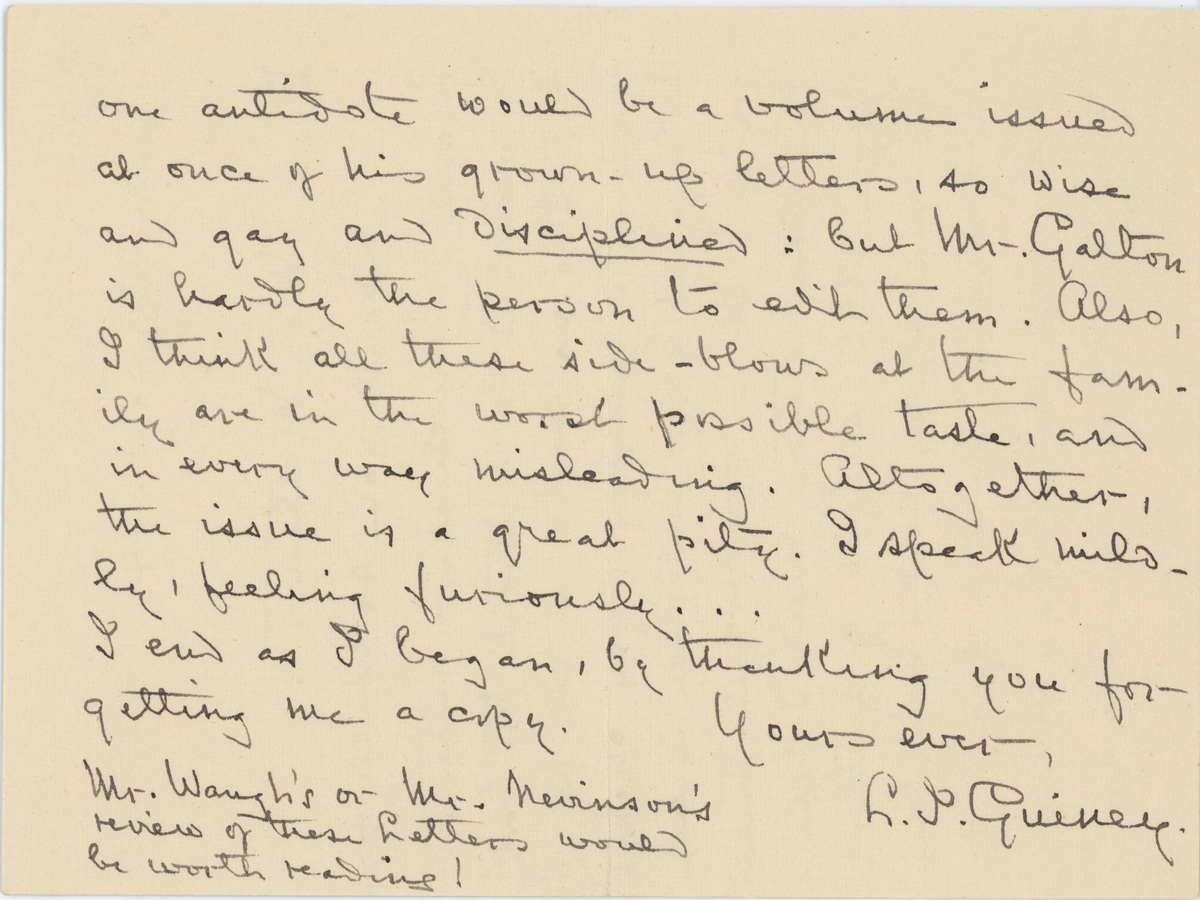

Alice Brown describes Guiney's letters with intense detail and praise, "To speak of her letters, those floating immoralities she cast about with so prodigal a hand, is to wonder anew at an imaginative brilliancy even beyond what she put into her considered work. To open one was an event." She speaks very highly of the beauty of her handwriting and the "line of grace" she kept in the physical structure of her letters. She describes the subject of her letters, "as varied as flowers and jewels and shells." Brown even claims that in her letters, she perhaps lost her typical academic restraints and was able to write better than most of her prose. She also writes about Guiney's generosity and good nature in her willingness to listen, respond quickly and review Brown's own works, "wherein you were praised to the top of your deserts, your failings touched lightly but honestly and your errors spotted with the scholar's acumen...". In Letter 1, her correspondence with a Miss Brown, conveys her enthusiasm and willingness to share her work. Miss Brown planned to use some verses of Guiney's poetry to set to music. Guiney also wishes her a good recovery, after what appears to have been a period of ill health in Brown's life. In Letter 2 to her friend Florence, sent shortly after the New Year in 1909, gives an update on Guiney's travels and work. Writing from Auburndale, Massachusetts, she describes the winter weather stating, "The snow is some three feet deep, and the sun perfectly dazzling." She describes a voyage on the Cymric where she spent the majority of her time in her room due to seasickness and to avoid the press. She talks of "American inventiveness", after the press discovered she was travelling and decided to write that she had "...'published several volumes of verse while abroad!'" She gives Florence updates on other acquaintances and writers that they know and ends by sending hopes of a good trip to the Isle of Wight, even though she believes it to be "desperately unhistoric and somewhat dull and Hanoverian." In Letter 3 to Mr. Matthews, she reveals more about her scholarly work. She thanks him for Lionel's Winchester Letters. Lionel Johnson was a great friend and influence of Guiney's. She edited his poetry and also collaborated on a volume of his prose works. She describes her happiness at Lionel's transition of "washiness and floppy benevolence" in his writing as a young man to "the clear steady mind I knew from 1895, so full of authority and repose." She criticizes the editor for errors in the biographical page. Guiney also briefly mentions the reputation that Lionel had to some as a decadent, but says that from these letters people will pull what they want to say whatever rumors they want. She believes that Mr. Galton should not be the editor and is saddened over the "side-blows at the family" that are "in every way misleading". In Letter 4, she writes again to Mr. Matthews about the same topic, wishing that she could get the Lionel Letters back from the editor, Mr. Galton. She thanks him and wishes him well. In Letter 5, she writes to a Mr. Hurd, asking about two minor poets in the Transcript, for a man who is making an anthology. She also reflects on writers' journeys from "socks and pinafores" to great authors and includes herself in this journey saying, "It gives me an odd twinge".

Letter 1

Dear Miss Brown:

Pray do whatever you like, in setting my verses to music. 'A Song of the Lilac' has been set so often, that it might be well to slight it; but I should be interested to see your results with others which you mention. Many thanks for the kind expressions in you letter. I hope you are recovering your strength; and with all other good wishes besides that, I am

Very sincerely yours,

Louise I. Guiney

{Auburndale, Massachusetts, Oct. 29th 1896}

Letter 2

{Jan. 19, 1909}

Dearest Florence:

I sent the 'Arness to Miss O'Brien the third day after my arrival, and suppose she got it safe and sound, though she hasn't said so. Mother is delighted with the foot-gear, and wishes me to drown you with, or in thanks. She sends you, and Mrs. Hornsey too, her very gratefullest remembrances, and a belated Happy New Year. She is in splendid form. The snow is some three feet deep, and the sun perfectly dazzling. I have only got my nose once outside this remote door since I came! Who do you think were my fellow passengers on the Cymric but Mr. and Mrs. W.S. Sperry? I was hideously sick as usual, though the voyage was not a very rough one, and kept my room the whole time; so I saw no one. I had requested that my name should not appear on the passenger list, owing to my sentiments towards the newspaper press of my dear, my native land; but no sooner had the gangway been fixed at the dock than a young man shot straight at me, fixed me with an adoring brown eye, and began a half-sentence in which "Oxford" and "poems" figured;_ when I promptly chewed off his head. I don't often eat my fellow mortals, even when they are reporters! but I can, when occasion seems to demand it. How-ever, next morning me noble name was in type, and coupled with it the cussed information that I had 'published several[sic] volumes of verse while abroad! This American inventiveness, (to call it by its gentler name) beats the devil. Everybody whom I have seen, so far, gazes open-mouthed upon my rotundity. The ribald Nortons are among 'em. Blanche Bigelow is living at Wellesly now, and was here yesterday, looking rosy, and fashionable in blue. Mrs Sutherland of Beacon St. (the playwright: did you know her?) died just before I got here, an accident resulting in some severe burns, and then heart failure. I was very fond of her. I hope the Isle of Wight (which I always think of as desperately unhistoric and somewhat dull and Hanoverian) was good to you ?

Yours with love,

L.I.G.

{Auburndale, Mass tts. U.S.A.}

Letter 3

{Amberley, Sept. 24, 1919}

Dear Mr. Mathews:

Thank you so much for Lionel's Winchester Letters. I wouldn't be without the book; but it is no service at all to death!s memory; you ought to be glad your imprint is not on it! It is wonderful that the clear steady mind I knew from 1895, so full of authority and repose, could have been at seventeen such a surge of washiness and floppy benevolence and super-Shelly-an nothingarianism | I think little of the judgment of those who had these letters printed. The editor writes badly; also, he has filled the first (biographical) page with mis-statements and half-statements. I suppose who would not for worlds strengthen the old lying rumour about Lionel: that he too was a decadent; but there are passages in these unguarded utterances of a remarkable boy thrashing out his thoughts, which will be quoted apart from their contexts, to the end. I not only fear, but know they will. The one antidote would be a volume issued at once by his grown-up letters, so wise and gay and disciplined: but Mr. Galton is hardly the person to edit them. Also, I think all these side-blows at the family are in the worst possible taste, and in every way misleading. Altogether, the issue is a great pity. I speak mildly, feeling furiously...

I end as I began, by thank you for getting me a copy.

Yours ever,

L.I. Guiney

Mr. Waugh's or Mr. [Nevinson's?] review of these Letters would be worth reading!

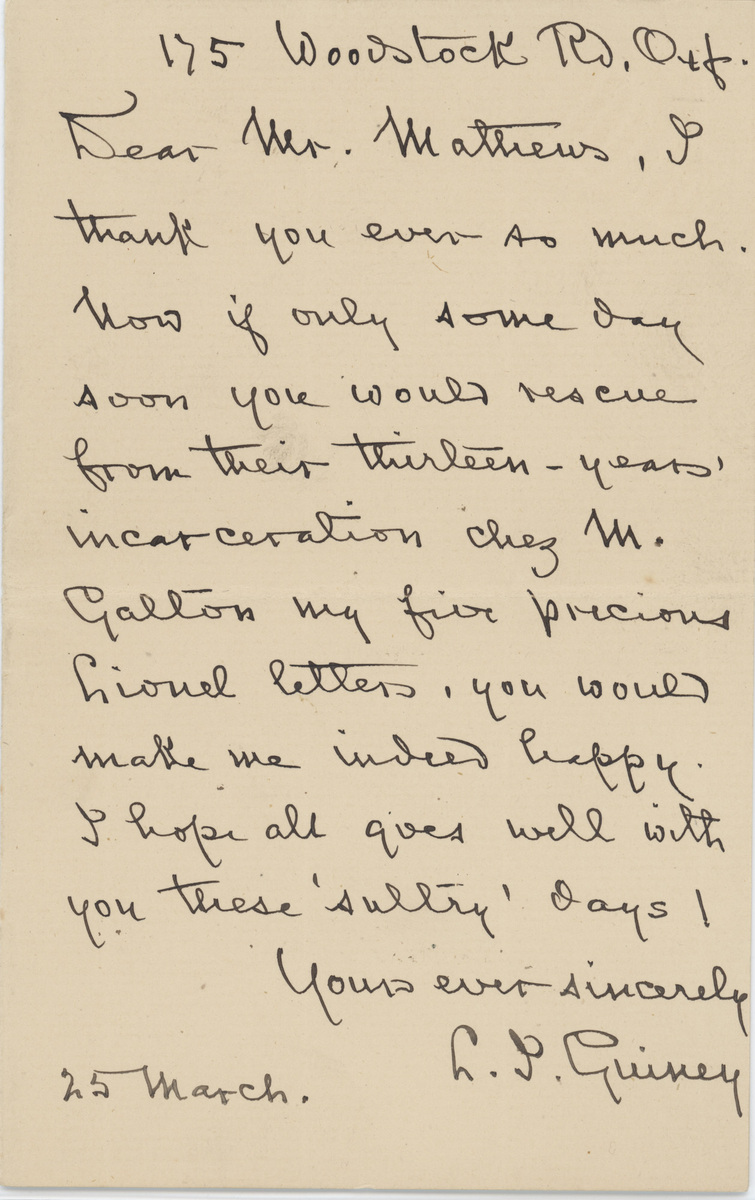

Letter 4

{175 Woodstock Rd., Oxf.}

Dear Mr. Mathews,

I thank you ever so much. Now if only some day soon you would rescue from their thirteen-years' incarceration chez M. Galton my five precious Lionel Letters, you would make me indeed happy. I hope all goes well with you these 'sultry' days!

Yours ever sincerely,

L.I. Guiney

{25 March}

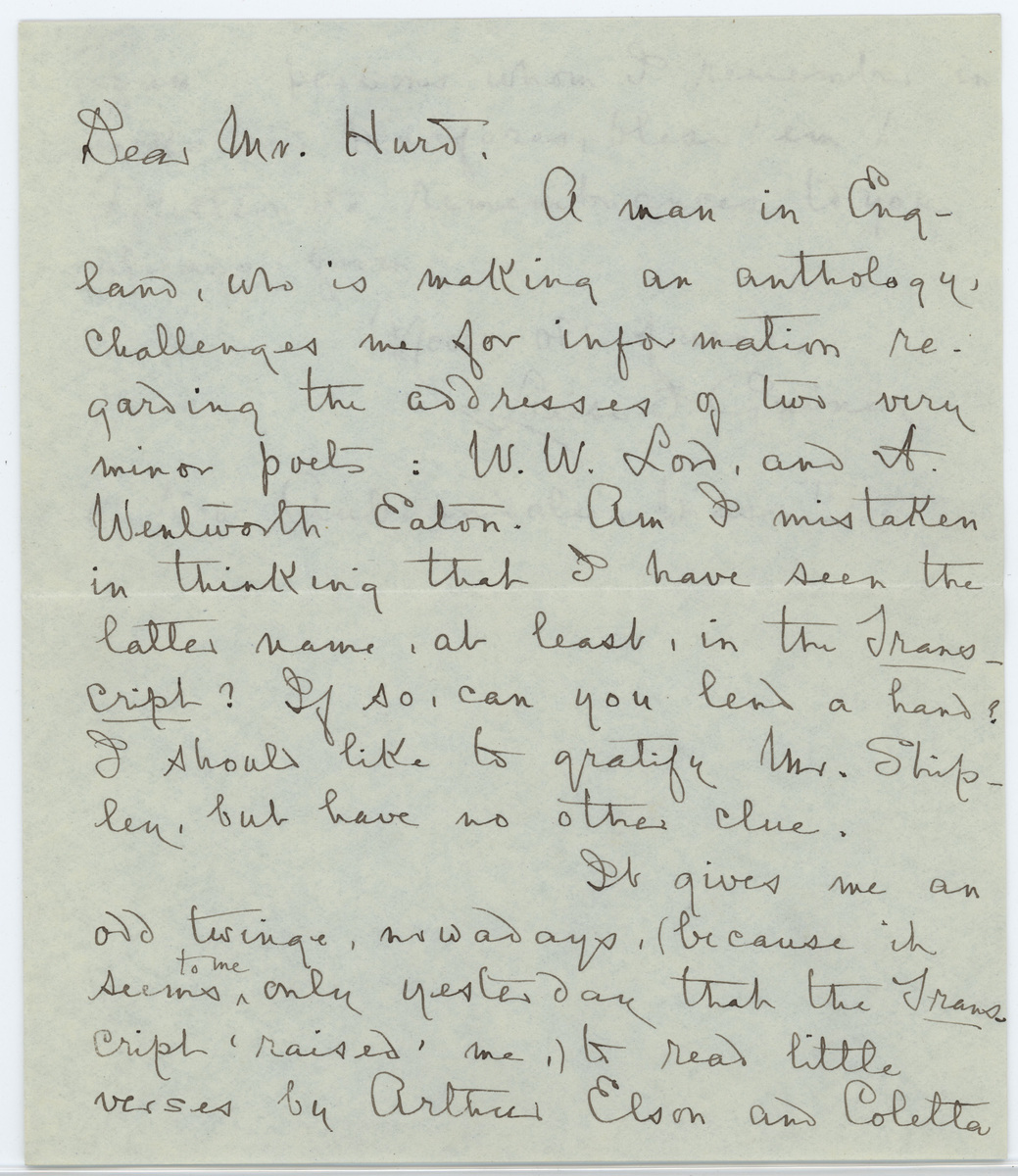

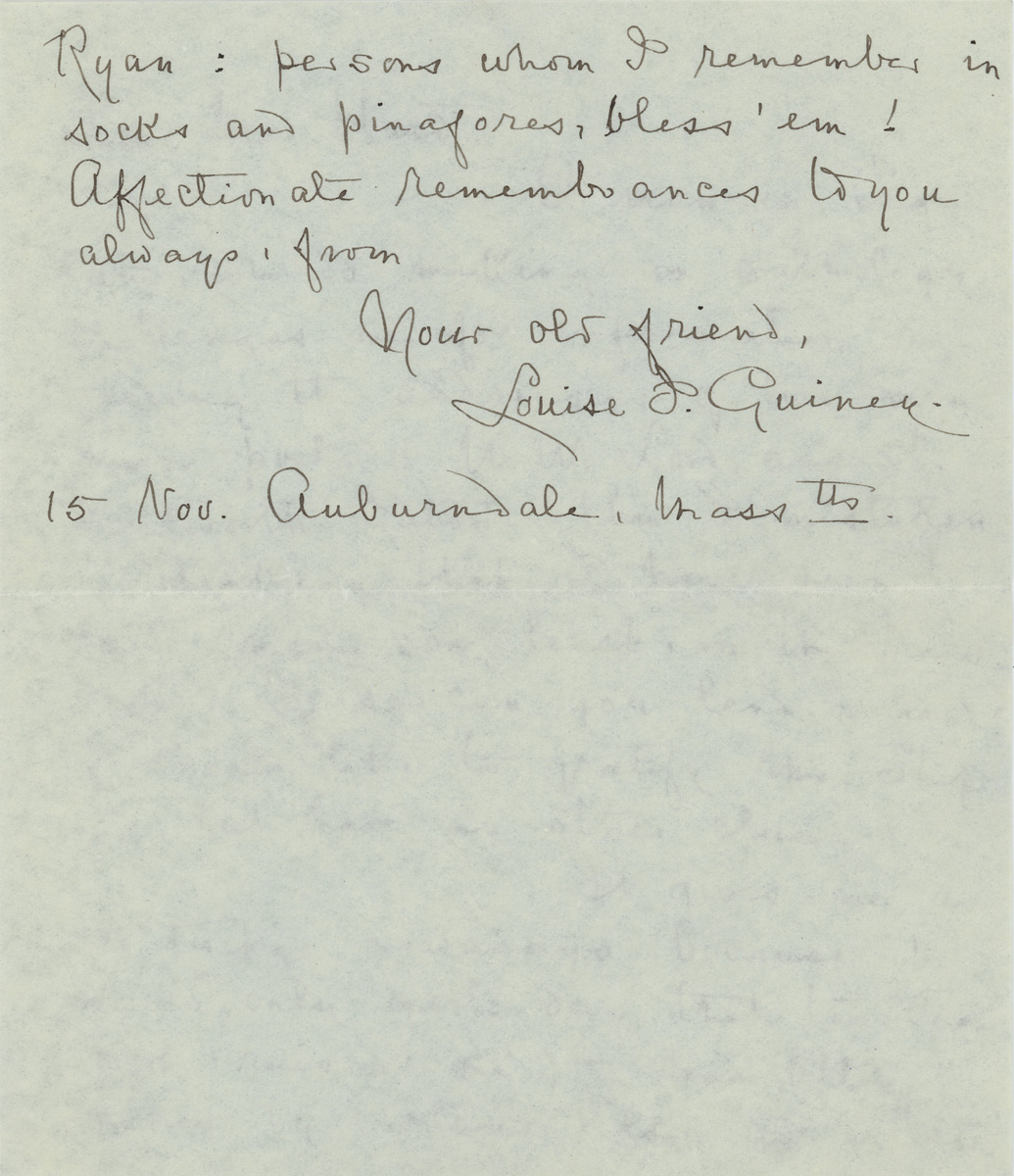

Letter 5

Dear Mr. Hurd,

A man in England, who is making an anthology, challenges me for information regarding the addresses of two very minor poets: W.W. Lord, and A. Wentworth Eaton. Am I mistaken in thinking that I have seen the latter name, at least, in the Transcript? If so, can you lend a hand? I should like to gratify Mr. Shipley, but have no other clue.

It gives me an odd twinge, nowadays, (because it seems to me only yesterday that the Transcript 'raised' me,) to read little verses by Arthur Elson and Coletta Ryan: persons whom I remember in socks and pinafores, bless 'em!

Affectionate remembrances to you always, from

Your old friend,

Louis I. Guiney

{15 Nov. Auburndale, Mass tts.}

Works Cited/Consulted

Brown, Alice. "An American Poet: Louise Imogen Guiney." The North American Review. 213.785 (1921): 502-517. Print.

Brown, Alice. Louise Imogen Guiney. New York: Macmillan Company, 1921. Print.

Leggott, Michele J. "Louise Imogen Guiney (7 January 1861-2 November 1920)." American Poets, 1880-1945: Third Series. Ed. Peter Quartermain. Vol. 54. Detroit: Gale, 1987. 136-147. Dictionary of Literary Biography Vol. 54. Dictionary of Literary Biography Complete Online. Web. 17 Apr. 2015.

"Louise Imogen Guiney." Poetry Foundation. Poetry Foundation, n.d. Web. 17 Apr. 2015.