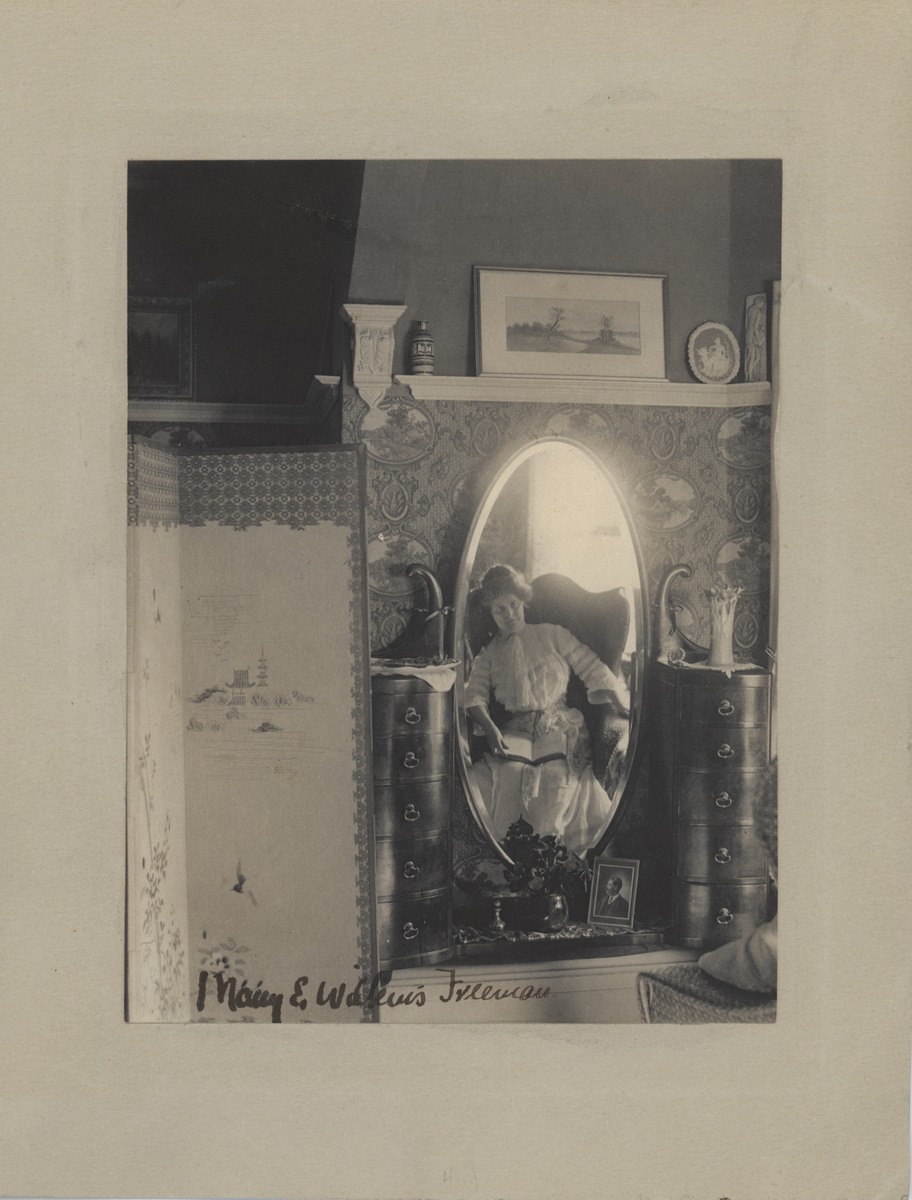

Mary E. Wilkins Freeman

Mary Eleanor Wilkins Freeman was born on October 31, 1852 in Randolph, Massachusetts into a family that descended from ancestors who were a part of the Colony of Massachusetts Bay in the 17th century (Westbrook). Her father was Warren E. Wilkins Freeman and he worked in home carpentry. Her mother was Eleanor Lothrop Wilkins. Randolph, Massachusetts was a largely agricultural town with a large concentration of shoe manufacturing. The family, as well as majority of the town, strictly adhered to an Orthodox Congregationalism, which maintained Puritanical values that were inherent in the New England culture of the time and would heavily influence Freeman's works. Due to economic plight, Warren moved the family to Brattleboro, Vermont where he started a dry-goods business. At the same time, Mary went to high school and graduated in 1870, after which she attended the strictly religious Mt. Holyoke Female Seminary but dropped out after a year because of ill health. She then took courses at home and attended Glenwood Seminary in West Brattleboro from 1871-1872. The financial situation for the Freeman's became so dire that Mary's mother, Eleanor was forced to go into service for the household of Reverend Thomas Pickman Tyler. This was also the time when Mary sold her first work, a children's ballad entitled, "The Beggar King", in order to help alleviate her family's economic stress. Unfortunately, her father's business failed and in 1880 her mother died. A couple years later, Mary started to produce adult fiction, which appeared in newspapers and in Harpers Bazaar. At this time she started to be recognized as a significant writer and wrote frequently for the publishing firm of Harper and Brothers. Her father died in 1883, before she experienced any real success. After his death, she moved back to Randolph, where she lived on the family farm of her dear friend Mary Wales for twenty years. During this time, relieved from household duties by Wales, she often worked for 10 or more hours a day on her writing.

Her works were considered "local colour" and almost entirely focused on the lives, experiences and conditions of lower classes and working people, especially women, in rural New England. She explored the lives of women and the relationships that they shared, particularly choosing to focus on power dichotomies (Lauter). Her works are considered to be social commentary on the time, revealing the economic and spiritual decline of the era. She claims that her works are, "intended as a study of the human will in several New England characters, in different phases of disease and abnormal development and to prove...the truth of a theory that its cure depended entirely upon the capacity of the individual for a love which could rise above all considerations of self..." (Westbrook). She revealed the effects of Puritan values through the themes of honesty, morbid conscientiousness, passivity, and the overdeveloped will and its' peculiarities (Westbrook). Her works also effectively portray the tension between a modernizing world and the cultural and economic situation of rural New England and how the two worked in relation with one another, as opposed to separate from one another (Lauter). In her lifetime she wrote 15 volumes of short stories, 50 uncollected short stories, 14 novels, three volumes of poetry, three plays, eight children's books and prose essays.

Her productivity started to slow significantly when at the age of 49 she decided to marry Dr. Charles M. Freeman and move in with him in Metuchen, New Jersey. In Metuchen, separated from the place where she received inspiration for her local colour stories, she found nothing to write about. Her marriage while at first pleasant, started to deteriorate when Dr. Freeman turned to alcoholism. He forced Mary to write more to help to financially keep up his drinking habit. Eventually, Dr. Freeman was institutionalized and Mary obtained a legal separation. Towards the end of her life, she was honored with the William Dean Howells Gold Medal for Fiction and was elected to the National Institute of Arts and Letters, both in 1926. She died of a heart attack on March 13, 1930 in Metuchen, New Jersey.

In Letter 1, Freeman writes to a friend from her long-time home in Randolph, Massachusetts. She references "the haunt of my spinsterhood", something she took pride in and often wrote about in her works. She also references her divorce with Dr. Freeman. These issues of spinsterhood and her divorce very well could have effected her when writing this letter as she says, "...wonder if you can read a word of this" and, "I don't think you know who is writing, unless nobody else writes such absurdities." Her handwriting was particularly more difficult to decipher in Letter 1 than in her other letters. She then, discusses an election for which she is a candidate and who will vote for her. Letter 2, written to Mr. Pratt, reveals more about her writing process. She promises to write him "another" story soon, when she is not so busy with her other work. She also talks about her preference for not making business promises, and dislike for getting entangled in such matters. Mr. Pratt requested a photograph from her, of which she is hesitant because she has had "many terrible pictures in the paper from a poor photograph". In Letter 3, we also get a glimpse into her work with a transaction for some of her writing. She states that she charges $50/1,000 words.

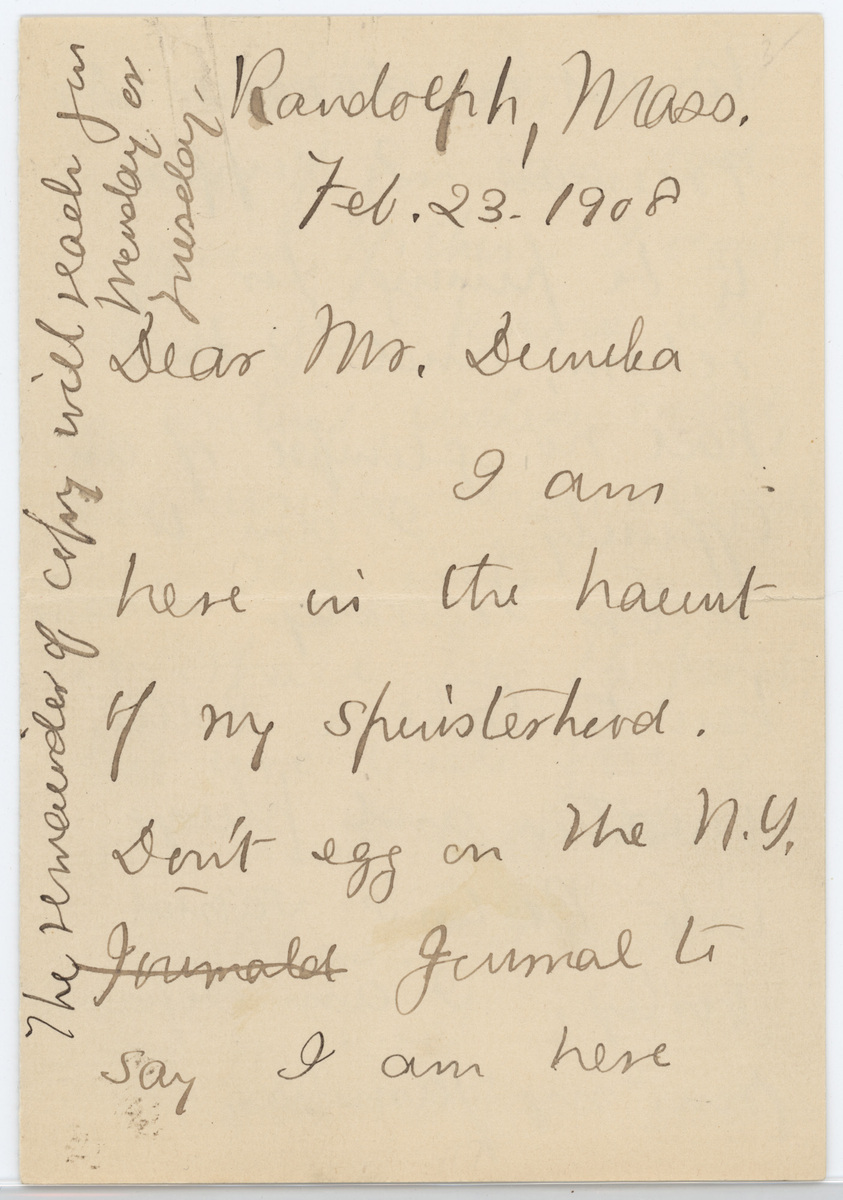

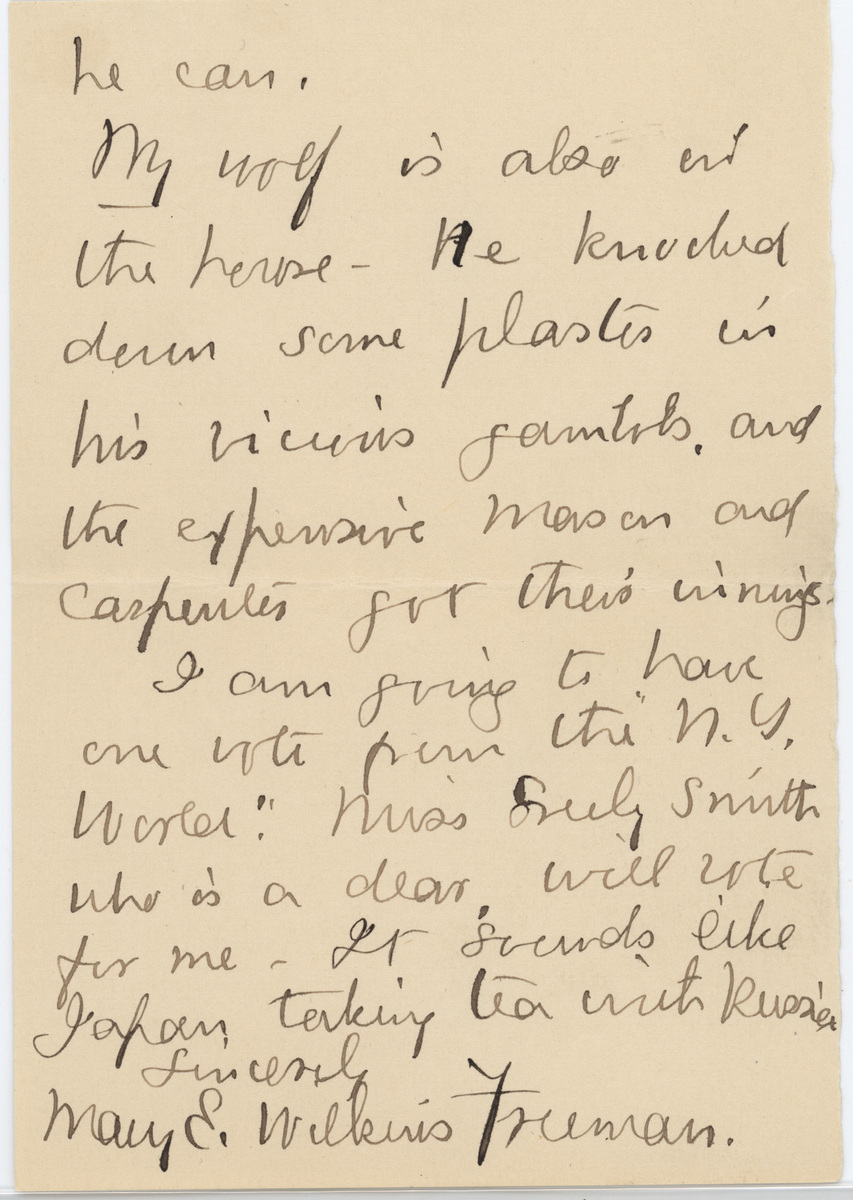

Letter 1

{Randolph, Mass. Feb. 23, 1908}

Dear Ms. D[illegible],

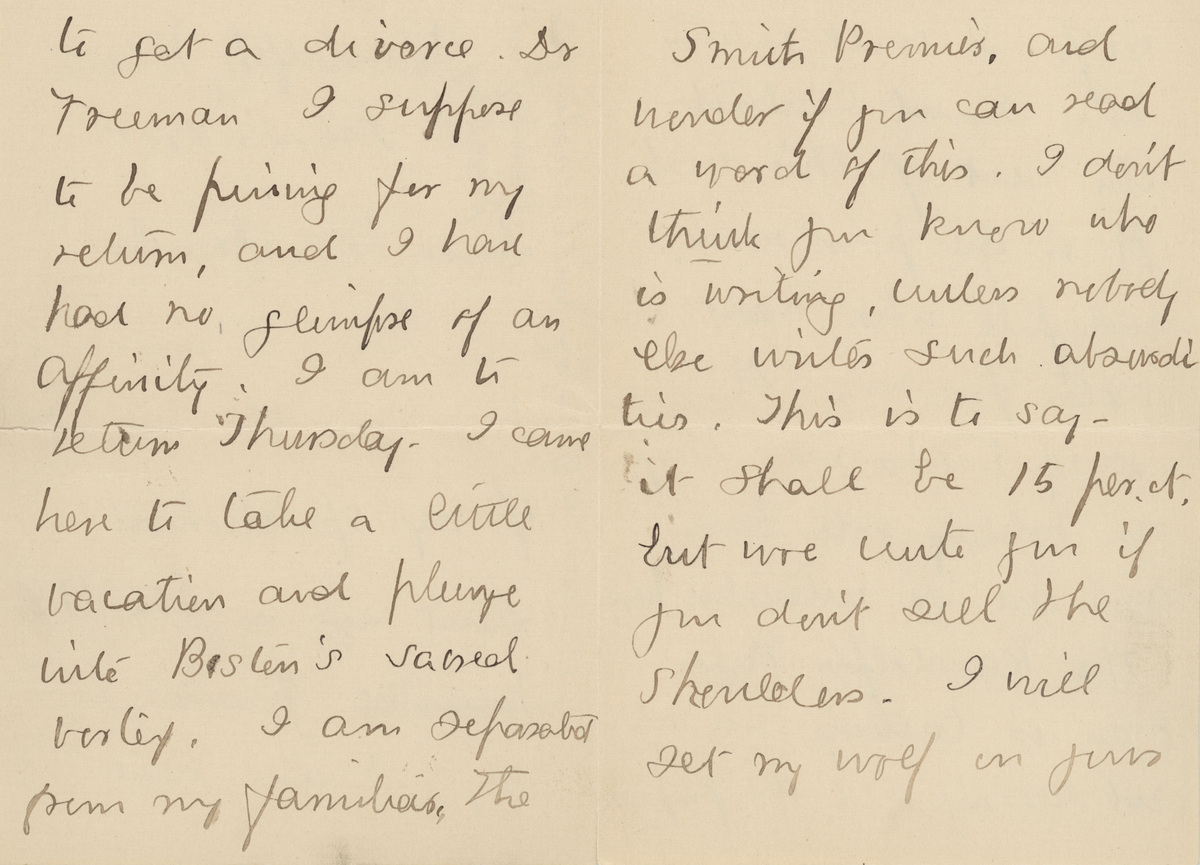

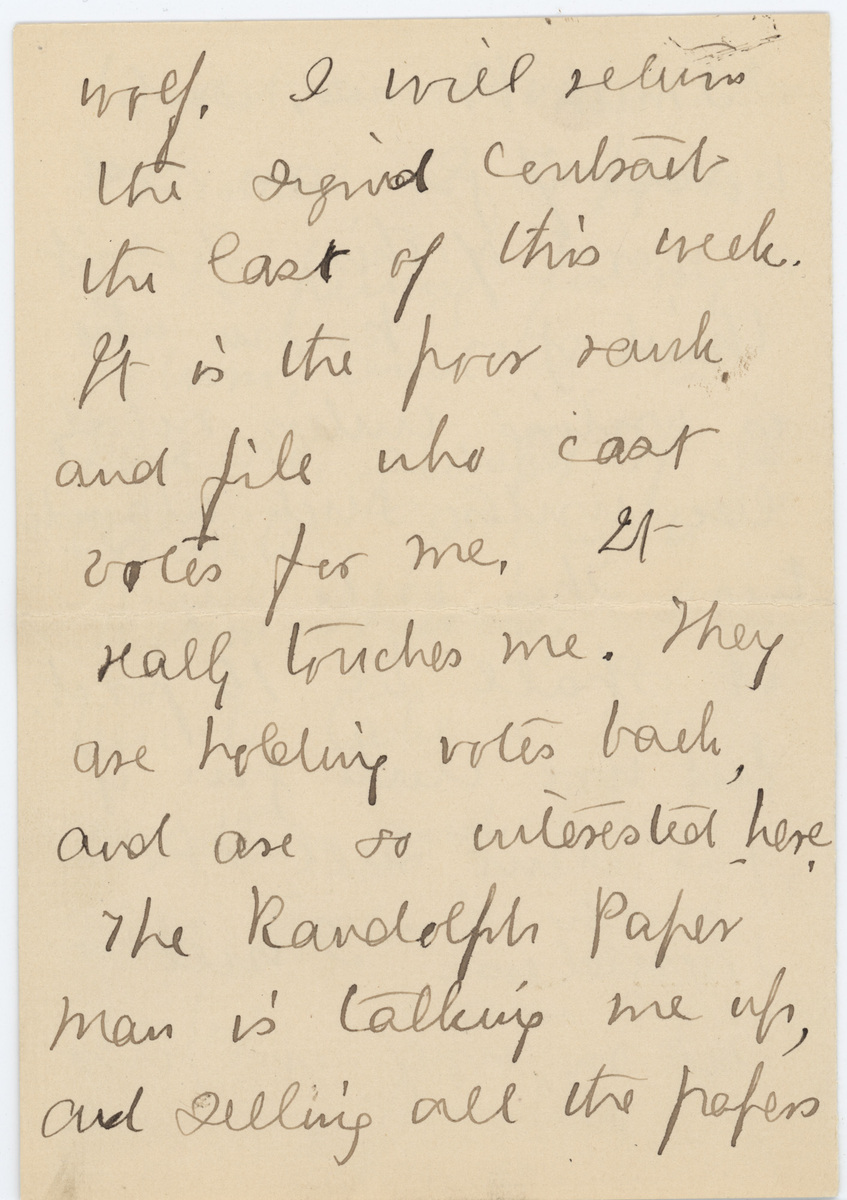

I am here in the haunt of my spinsterhood. Don't egg on the N.Y. Journal to say I am here to get a divorce. [As?] Freeman I suppose to be pining for my return, and I had had no glimpse of an affinity. I am to return Thursday. I came here to take a little vacation and plunge into Boston's [sacred?] belief. I am separated from my familiar, the Smith P[illegible], and wonder if you can read a word of this. I don't think you know who is writing, unless nobody else writes such absurdities. This is to say - it shall be 15 percent but woe unto you if you don't [sill?] the shoulders. I will get my wolf on [illegible] wolf. I will return the [illegible] C[illegible] the last of this week. It is the poor rank and file who cast votes for me. It really touches me. They are holding votes back, and are so interested here. The Randolph Paper man is talking me up and selling all the papers he can. My wolf is also [illegible] the horse. He knocked down some plaster in his vicious gambles and the expensive mason and carpenter got their winnings. I am going to have one vote [from?] the "N.Y. World." Miss [illegible] Smith who is a dear, will vote for me - It sounds like Japan taking tea with Russia.

Sincerely,

Mary E. Wilkins Freeman

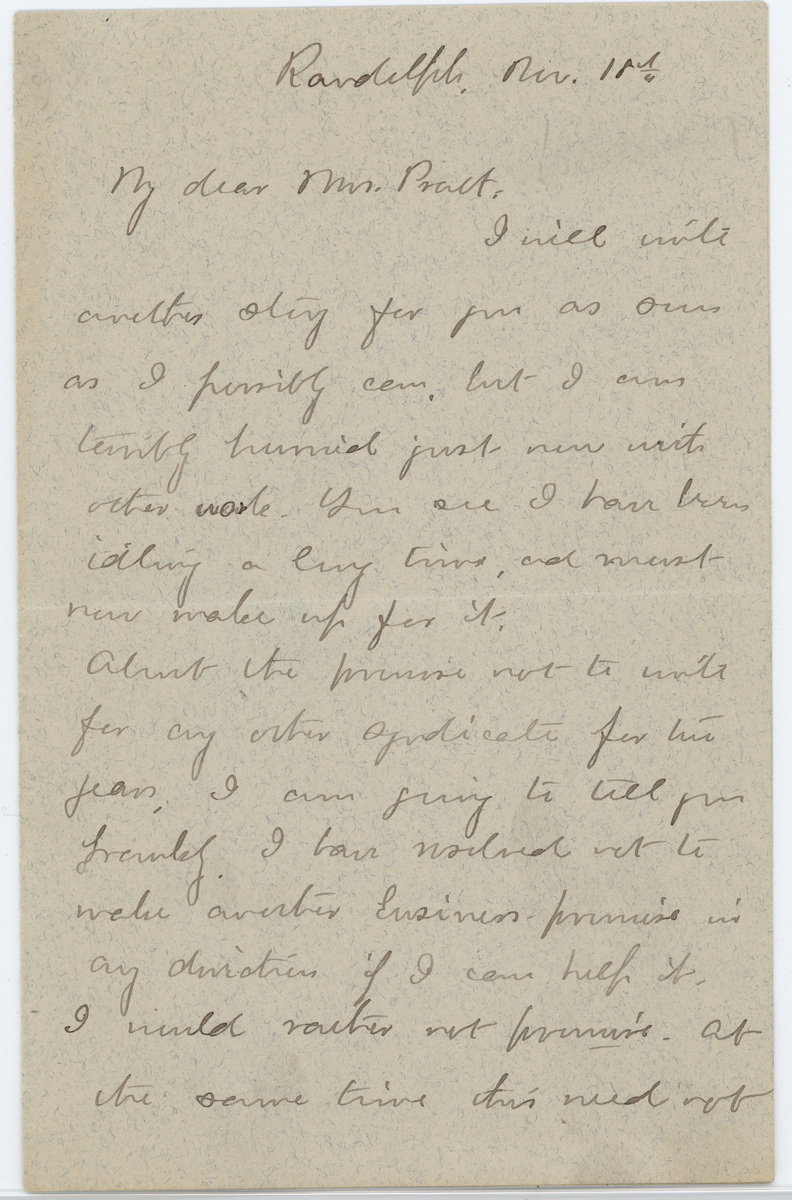

Letter 2

{Randolph, Nov.18th}

My dear Mr. Pratt,

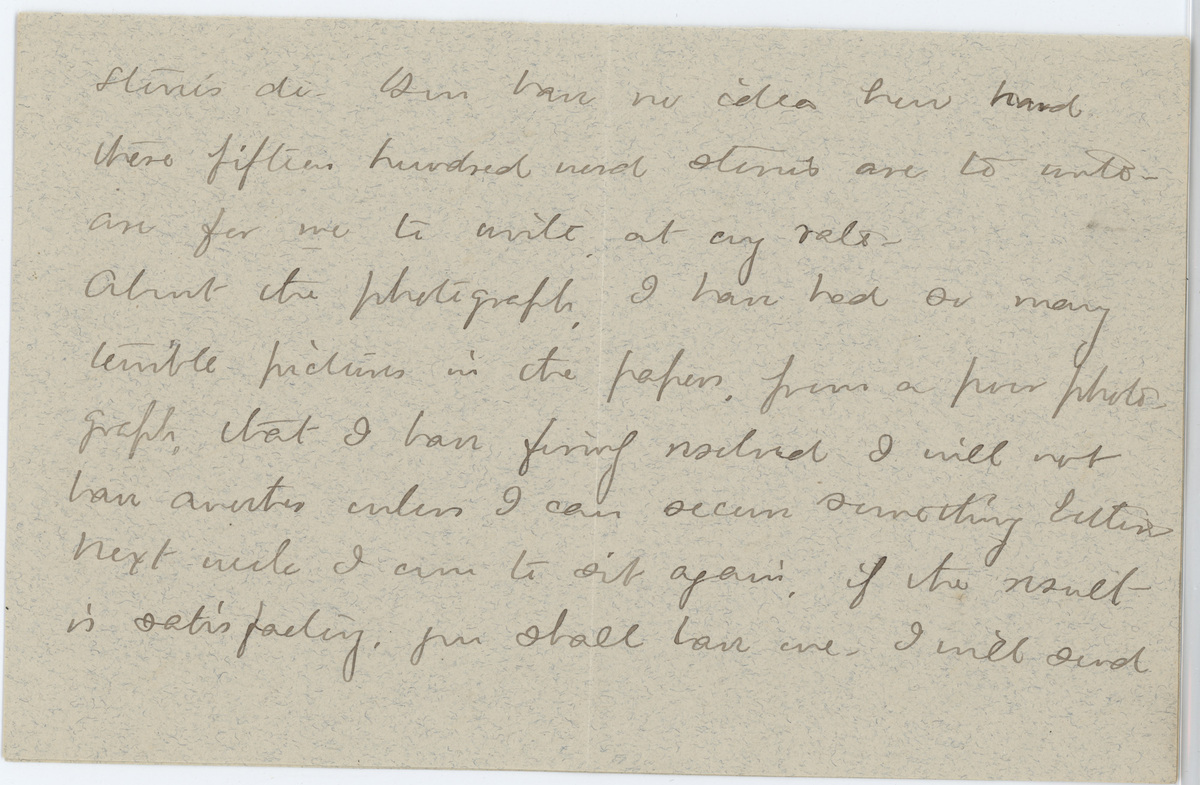

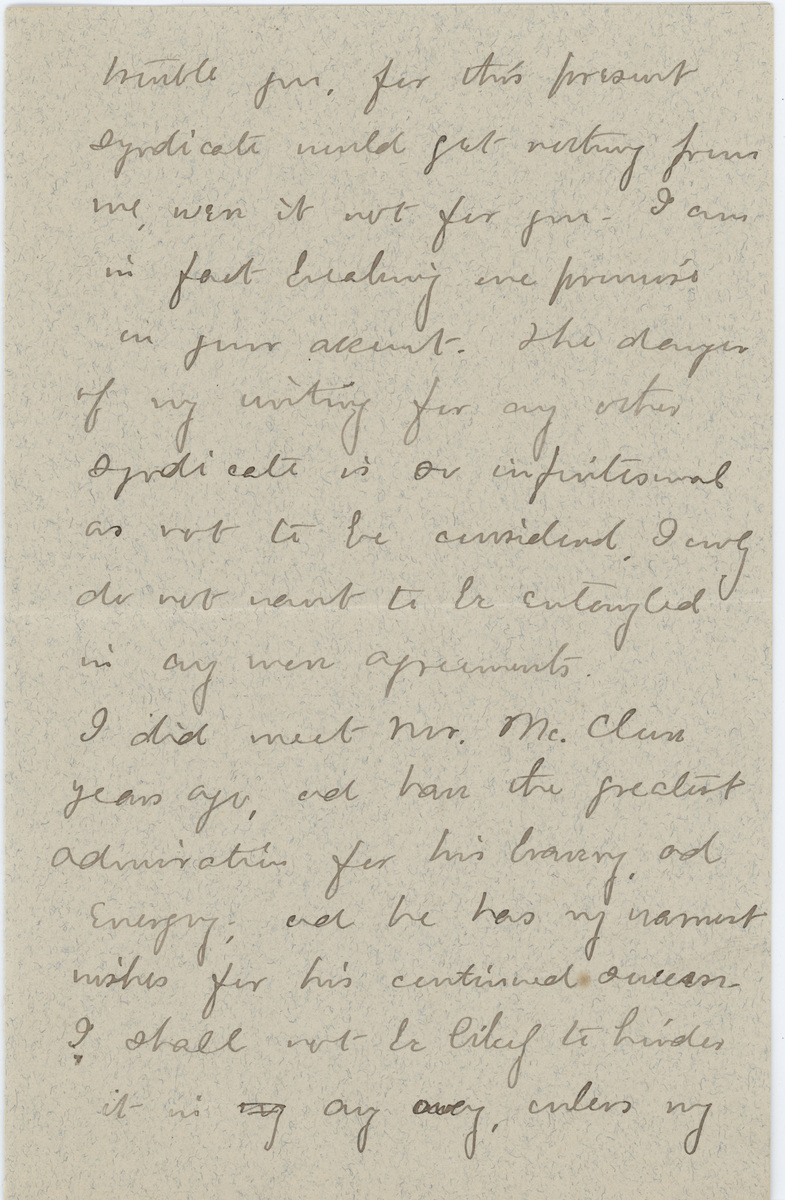

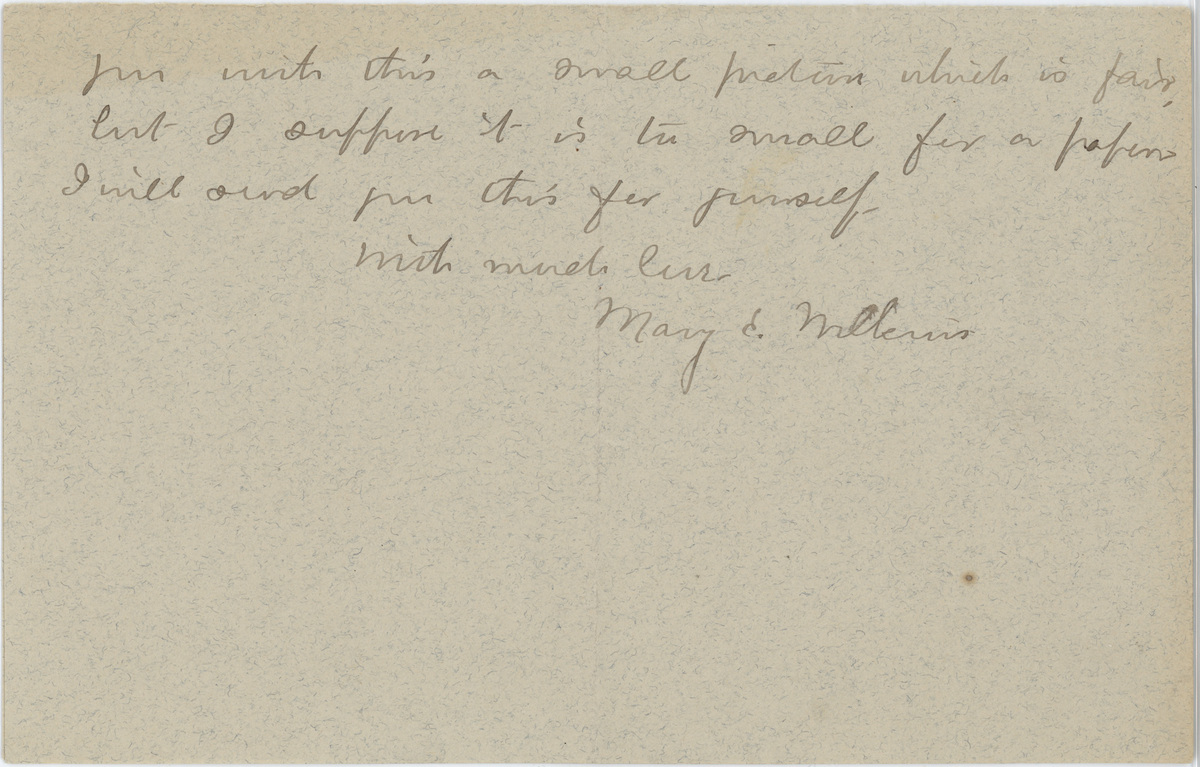

I will write another story for you as soon as I possibly can but I am terribly [humid?] just now with other work. Y[illegible] [illegible] I have been idling a long time and must now make up for it. About the promise not to write for any other syndicate for two years. I am going to tell you frankly. I have resolved not to [illegible] [illegible] business promise in any duration if I can help it. I would rather not promise. At the same time this need not [humble?] you, for this present syndicate would get nothing from me. I am in fact breaking my promise in your [account?]. The depth of my writing for any other syndicate is as infinitesimal as not to be considered. I only do not want to be entangled in any new [appointments?]. I did meet Mr. Mc[illegible] years ago, and have the greatest admiration for his bravery and energy and he has my warmest wishes for his continued success. I shall not be likely to hinder it in any way, unless my stories do [illegible] have no idea how hard these fifteen hundred word stories are to write - on for me to write at my rate. About the photograph, I have had as many terrible pictures in the paper from a poor photograph that I have [illegible] [illegible] I will not have another unless I can secure something better next week I am to [sit?] again. If the result in satisfactory, you shall have one. I will send you with this a small picture which is fair, but I suppose it is too small for a paper. I will send you this for yourself.

With much love,

Mary E. Wilkins

Letter 3

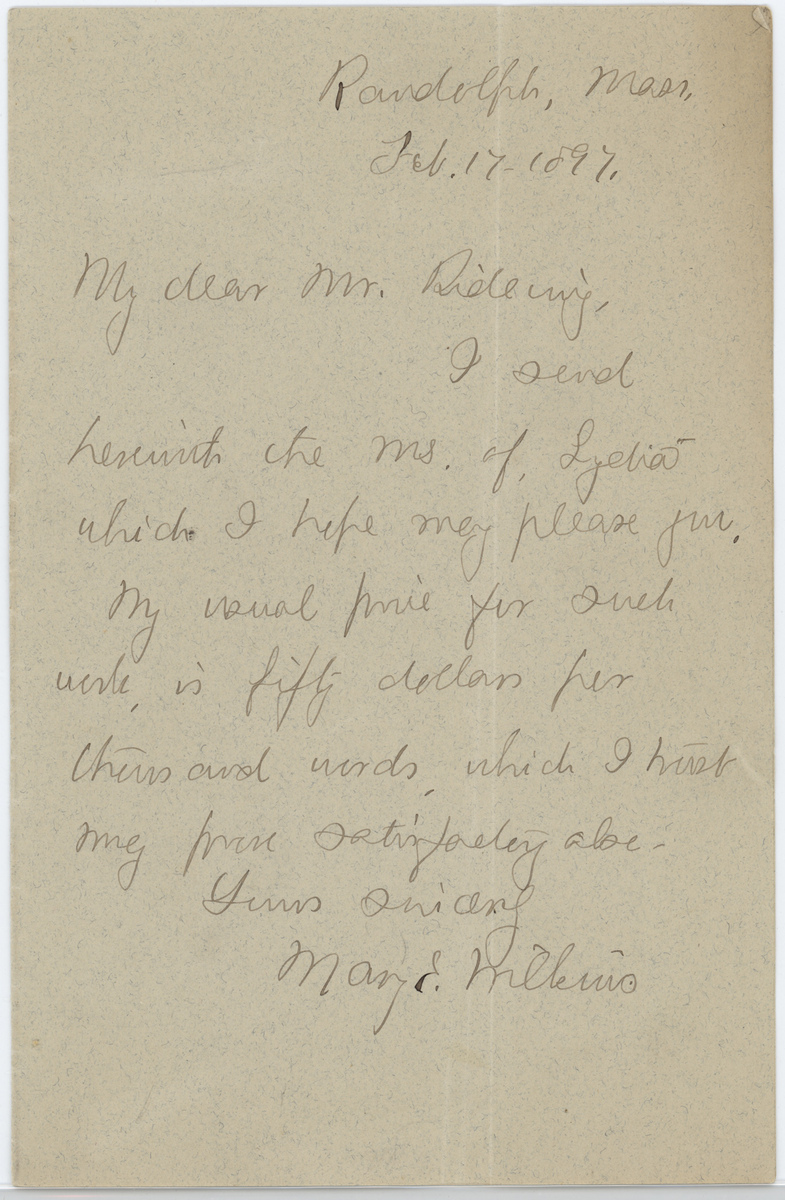

{Randolph, Mass. Feb. 17, 1897}

My dear Mr. [Riding?],

I send herewith the Ms. of Lydia which I hope may please you. My usual price for such work is fifty dollars per thousand words which I [hope?] may prove satisfactory also. Yours sincerely,

Mary E. Wilkins

Works Cited/Consulted

Csicsila, Joseph. "Mary Wilkins Freeman". In Oxford Bibliographies Online: American Literature. 15-Apr-2015.

Glasser, Leah B. "Mary E. Wilkins Freeman." Heath Anthology of American Literature. Cengage Learning, n.d. Web. 15 Apr. 2015.

"Mary Eleanor Wilkins Freeman". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 2015. Web. 15 Apr. 2015

Reichardt, Mary R., and Mary Eleanor Wilkins Freeman. Mary Wilkins Freeman: A Study of the Short Fiction. New York: Twayne, 1997. Print.

Reuben, Paul P. "Chapter 6: Mary Wilkins Freeman." PAL: Perspectives in American Literature- A Research and Reference Guide.

Westbrook, Perry D. "Mary E. Wilkins Freeman (31 October 1852-15 March 1930)." American Short-Story Writers, 1880-1910. Ed. Bobby Ellen Kimbel and William E. Grant. Vol. 78. Detroit: Gale, 1989. 159-173. Dictionary of Literary Biography Vol. 78. Dictionary of Literary Biography Complete Online. Web. 15 Apr. 2015.